Since their creation less than a hundred years ago, superheroes have effortlessly captured our imagination. Studios seem incapable of making non-superhero movies and television executives are following suit. As the superhero genre expands past the pages of the pulpy comic book, it has to evolve and grow. A great example of this growth is the show Breaking Bad, particularly in its depiction of the character Walter White. A close look at Breaking Bad will reveal its underlying superhero DNA and how Vince Gilligan, the show’s creator, used the superhero genre to expound on his hypothesis.

First, a brief history of the origin of the superhero figure. The modern American superhero is derived from hundreds of years of hero figures. The superhero genre has its roots in myths, with figures such a Odyssey or Robin Hood linking the notion of heroism and bravery to justice and fairness. In the era directly preceding what would come to be known as the “Golden Age” of superheroes, figures such as Doc Savage, Tarzan, and the Phantom laid the foundation by contributing certain genre elements such as a double identity, masked costumes, and superhuman strength. Arguably, one of the direct ancestors is the Scarlet Pimpernel, the dashing protagonist of Baroness Emma Orczy’s same titled play and subsequent novels. Each iteration brought us closer to what is undeniably the first superhero; Superman. Adorning the iconic cover of Action Comics #1, Superman ushered in a new age and helped establish a new literary genre. Batman and Wonder Woman followed suit and helped codify the genre. The genre has grown by leaps and bounds, no pun intended. A new generation of writers, artists, and creators pushed the boundaries of the established classification in the Silver Age of Comics, with figures such as the Hulk, Spiderman, and the Flash redefining the genre.

>Delving deeper into the specifics, let’s look at the definition and the various elements that comprise a superhero figure.

When we meet the mild-mannered Walter White with his alliterative alter-ego sounding name, he is working two jobs to make ends meet. His life is bleak, and it gets bleaker when he finds out he has cancer. Walt undergoes chemotherapy and pumps toxic chemicals into his body to fight the tumorous lung cells. As the chemicals course through his veins, Walt has to resort to increasingly desperate measures to pay for his treatment.

Historically, chemicals/ chemistry as an agent of change is a common trope in comic books, especially in the Silver Age of Comic Books. A radioactive spider bite mutates Peter Parker’s DNA, gamma radiation transforms Bruce Banner into the Hulk. And the anti-carcinogen chemicals used in chemotherapy allow for the creation of Walt’s alter-ego, Heisenberg. As Walt starts cooking methamphetamine to make money for his family, he gets pulled deeper into the drug world. Initially just a pseudonym to protect his identity, Heisenberg ultimately becomes the persona Walt uses in that world. This development happens over the course of the first season, culminating in an explosive scene where Heisenberg has ostensibly bested his first arch-nemesis, Tuco.

Heisenberg Intro CLIP

This is arguably the first appearance of Walt’s alter-ego, Heisenberg. Unlike Walter, Heisenberg is self-assured and confident. He is able to hold his own against an aggressive and unstable drug dealer and he only grows stronger.

The reason Walter White continues to make methamphetamine despite the danger is for the money. Well, not just the money.

While solid, hard cash pays for his treatment, it also then serves as a nest egg and a protection of sorts for Walt’s family- his wife, Skyler, his son Walt Jr (immediately a properly sympathetic character), and his as yet unborn daughter. Walt’s prowess at organic chemistry, even for a brilliant student from the California Institute of Technology, border on the fantastical. He is able to make an incredibly pure thus potent version of meth, “Blue Sky” which even addicts recognize as being superior. Early in the first season, Walt gets rid of the evidence of a murder using the dissolving powers of hydrofluoric acid to destroy a human body. He creates a mini-bomb from fulminated mercury which he uses to destroy Tuco. In season 2’s episode “4 Days Out”, Walt constructs a mercury battery using chemicals, coins, and galvanized metal for the chargeless RV, rescuing Jesse and himself from dire straits and making MacGyver proud. Walt may have the goods, but Heisenberg is able to deliver them.

Any respectable superhero must have a sidekick, and Walt would be bereft without Jesse Pinkman, or Cap’n Crunch as he’s known in the meth head circle. Walt chances upon Jesse escaping during a DEA ride along, and convinces him to help cook and sell meth. Jesse is Walt’s sidekick, helping him navigate the seedy world of drug dealing, while providing a skewed moral compass. They even have their own version of the Batmobile, the RV. It can’t fly, but it does allow them to cook in undisturbed peace and a place to store their equipment. Despite his complicity in Walt’s dealings, Jesse remains an innocent figure, even by the end of season 5.

Finally, what would a superhero be without a costume? Naked, unrecognizable. Heisenberg’s iconic porkpie hat elevates his status from measley high school teacher to drug lord. By Season 3, Heisenberg has accumulated a reputation for himself and is known by his hat.

But is Walter White a superhero or a supervillain?

In Peter Coogan’s book, “Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre”, he outlines 5 main types of supervillains; the monster, the enemy commander, the mad scientist, the criminal mastermind and the inverted superhero-supervillain. While Walter definitely displays aspects of the mad scientist and the criminal mastermind, he is a great representation of the last type of supervillain; the inverted superhero-supervillain. Walter clearly views himself as a “good guy”, a man kept down by the fates but his actions are those of a self-interested and selfish man. Season 2, Episode 12 “Phoenix” marks an important turning point in Walt’s character. Walt and Jesse are on the outs, and Walt is holding Jesse’s share of the drug money hostage until Jesse can prove his sobriety. Their relationship is further threatened by the interference of Jane, Jesse’s girlfriend. Walt arrives to confront Jesse and notices both Jesse and Jane in a deep drug-induced stupor. He inadvertently rolls Jane over on her back and she subsequently chokes to death on her own vomit, while Walt looks on, horrified but unwilling to intervene. His desire to be rid of Jane combined with his callousness towards an innocent life are classic supervillain traits.

Walt displays other traits typical of a supervillain. In season 5, Walt is given the opportunity to sell his share of the methylamine to a competitor and receive $5 million. He refuses to take the money and leave the meth business. This mania about needing to be the best and creating a drug empire is typical supervillain behavior. “You asked me if I was in the meth business or the money business. Neither. I’m in the empire business.” While he seems to have some remorse about the vile product he’s creating, it is fleeting at best. Any guilt Walt feels is overshadowed by his pride in the purity of the product. This pride in his criminal artistry is another one of the characteristics of a villain.

One major attribute of a supervillain is “the wound”. Many supervillains suffer from an original incident that leads them to battle the superhero. This wound, real or perceived, is essential to the identity of the supervillain, the core of what drives them to do ill. Walter believes what he has—not just the physical resources of supplies and equipment he possesses but more fundamentally, his native resources of intelligence and invention—is of infinite and absolute worth. He is not going to stop until he’s been fairly compensated for them, which means he’s never going to stop.

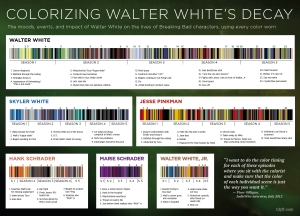

It’s not just the character of Walter White that draws inspiration from the superhero world. From the colorization to the cinematography, elements of graphic novels and comic books are evident in the look and feel of Breaking Bad. When comics were printed on pulpy, rough paper, they had to be brightly colored to sell. Superheroes had to recognizable when someone was scanning the newsstand. Vince Gilligan similarly colorized his characters through costuming. Walt’s sister-in-law Marie’s obsession with the color purple was treated as a joke, but it becomes her signature color. This meticulously prepared chart shows the color of each outfit the characters worse throughout the series. Delving a little deeper in the colors, we see that Walt starts off in neutral, bland earth tones. His obsession with money is reflected in the light greens. As he becomes Heisenberg, the colors get darker and muddier.

>Skyler is usually dressed in blues and whites, indicating her innocence and purity. In season 3, as she gets increasingly drawn into her husband’s web of lies and deceit, her clothes get darker. When she is fully immersed in a scheme to launder Walt’s drug money, Skyler is shown as wearing black and dark browns. She is once again depicted in lighter colors as she tries to extricate herself and her family from Walt’s drug empire. This type of color analysis can be done for Hank, Jesse, and Walt Jr. as well. Gilligan’s meticulous eye for colors and costuming reinforce who the characters are and the world they inhabit.

Gilligan’s careful consideration of color is evident in the cinematography and visual design of the show. In an interview with Creative Cow, Director of Photography Michael Slovis says about the show’s look:

One trademark in the show that’s terrific and that Vince and I talk about and exploit is that we often don’t see the faces of the main characters. Vince says that everyone knows who these people are so we really don’t need to see their faces…If I can tell the story in a pitch-black room with the face totally in silhouette, that’s what we do. It’s expressionistic. We represent reality, we don’t reproduce it. Another example of that are those colors in New Mexico. Those golden, orangey, yellowy colors don’t exist in real life… We take a very, very representational, emotionally based, expressionistic approach. The same thing goes with those wacky POV shots we do… nobody sees things from those angles but they serve the story.

As Slovis mentions, the show doesn’t aim to reproduce reality, just represent it. An example of Gilligan playing with representing reality is the color of Walt’s meth- Blue Sky. Using the chemicals Walt used meth should either be clear or tinged a slight yellow color. Gilligan makes the artistic choice to make it blue, a sky blue that reflects WW’s limitless pride, greed, and lust for power. An example of the colors that Slovis mentions as well as the expressionistic approach Gilligan and crew take is clearly reflected in the cold open of Season 3. The introduction of the cousins, Season 3’s big bad can be imagined easily in large columns of a graphic novel or a comic book.

Gilligan frequently uses canted and unique Point of View shots to establish WW’s looming presence. Whether using a camera mounted on the Roomba during a party scene or the shovel head when burying treasure, these POV shots firmly establish that this is an alternate reality. TV Worth Watching, a pop culture blog, compiled all the unique shots in Breaking Bad. This perspective of the characters is not typical of a drama since it is not from the point of view of the audience or another character. Despite dealing in real life situations, with blood, gore and violence, the cinematography indicates that Breaking Bad exists in an alternate reality. WW’s Albuquerque is Batman’s Gotham- a universe that is grimmer and grittier than the real world.

What does this reading of BB through the lens of the superhero genre award us? The very nature of comic books is that they are episodic and contain ongoing stories. Batman may defeat the Joker in this issue, but wouldn’t you believe it, the Joker returns. Marriages and even deaths are not permanent, and reboots offer a new creative team the chance of a fresh start and clean slate. Breaking Bad ran 5 seasons and had a clear narrative arc running through it. It is the story of how Walter White becomes Heisenberg and his subsequent downfall and redemption. While Walter’s story may have ended, the larger themes of addiction, search for power, and insatiable greed live on. The drug trade will continue to flourish without Heisenberg, people will buy, sell, create, barter, use, and abuse methamphetamine. Gilligan underscores the futility of the war on drugs by using elements of a genre that does not provide easy resolution. The players may change, new opponents rise and fall, but the story continues.

References

Coogan, Peter M., and Dennis O’Neil. Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre. Austin, TX: MonkeyBrain, 2006. Print.

Gilligan, Vince. “No Mas” Breaking Bad. AMC. 21 Mar. 2010. Television

Hutchinson, Gennifer. “Cornered'” Breaking Bad. AMC. 21 Aug. 2011. Television.

LaRue, John. “Infographic: Colorizing Walter White’s Decay.” TDYLF. N.p., 11 Aug. 2013. Web. 25 Jan. 2016. <http://tdylf.com/2013/08/11/infographic-colorizing-walter-whites-decay/>.

Mastras, George. “Crazy Handful of Nothin'” Breaking Bad. AMC. 2 Mar. 2008. Television.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics. New York: HarperPerennial, 1994. Print.

Slovis, Michael. “CreativeCOW.” CreativeCOW. Ed. Debra Kaufman. CreativeCow.Net, 2013. Web. 25 Jan. 2016. <https://library.creativecow.net/kaufman_debra/Behind-the-Lens-Michael-Slovis/1>.

________________

Shreya Durvasula is an Outreach Coordinator in Cambridge, Massachusetts and an avid TV enthusiast and blogger. This post grew out of a presentation she gave to the University of Maryland Honors course, “Deconstructing Breaking Bad”, which attempted to dissect what made Breaking Bad so compelling. Shreya’s guest lecture on the superhero genre as it applies to BB inspired a graphic novel student response, so she feels like she got the job done. You can read more of her writing here.