This is the first of a series of posts about art comics by women, combining reviews with critical attention to whether it matters that women wrote them. Bear with me through a little awkwardness; it’s been awhile since I’ve stretched these muscles.

In her response to last week’s “Gender and Cartooning in Chicago” thread, Erica Friedman gave an insightful and succinct summary of a theme that’s run through a number of recent HU posts: “Men represent men’s stories,” she said, “and set that as societal norm, so any women looking to rise in the field will have to write/draw those stories too or be relegated to an inferior ‘girl’s’ position.”

Hold that thought for a few paragraphs, will you, please?

_______________________________________________

Finnish artist Amanda Vähäm?ki’s The Bun Field (Campo di Baba) got a decent amount of attention from critics when it came out in English translation last summer (June 2009). If you haven’t read it, Bart Beaty gave the following summary of the action in his review of the original Italian publication :

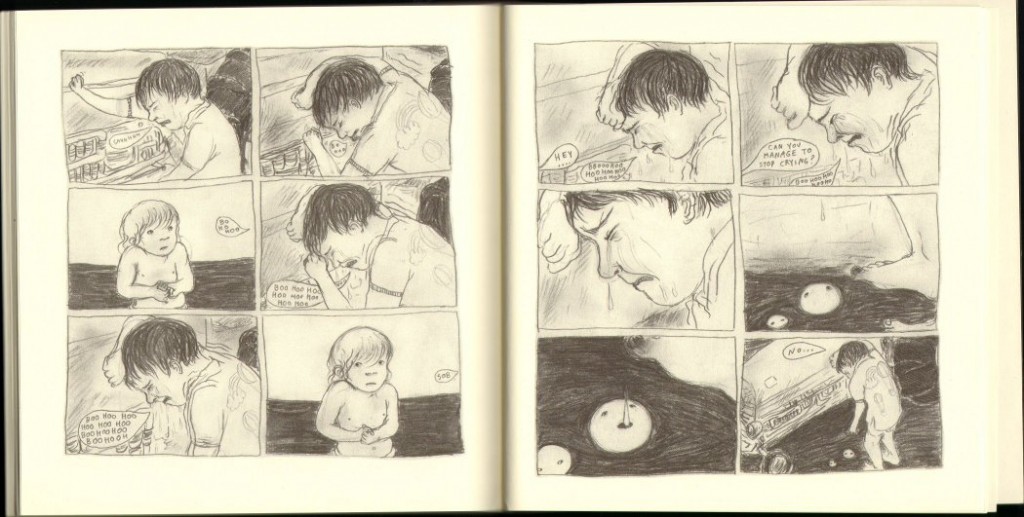

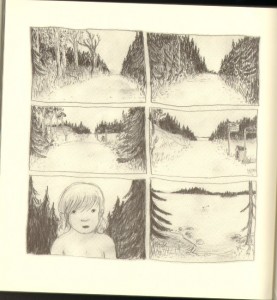

Campo de Baba is not much of a story, and it is probably not even a story at all in the classic sense of the word. A young man (sic) awakes from a dream — or does he? At breakfast he is confronted by a blob-like creature. He goes for a drive with a bear. He trades teeth with a dog. He is winked at by an apple. With a tractor, he slaughters a field. He disappears.

Most reviews of the English-language version follow Beaty’s lead and read it as a lushly drawn extended dream sequence that makes no particular attempt at specific meaning. Other critics, like Popmatters’ Sara Cole, go a little further and claim the book represents the “lived experience of a child,” the vulnerability and confusion, how nightmarish the adult world seems. But even Cole says it “lack(s) a coherent narrative.”

To the book’s credit and in defense of the reviewers, part of Vähäm?ki’s achievement is that the book satisfies equally well either way…

…but the incoherence is vastly overstated.

Up through the title scene, it works just fine to read The Bun Field using one or the other of these two interpretations. But the panels with the younger child on the bicycle don’t fit very well with those readings.

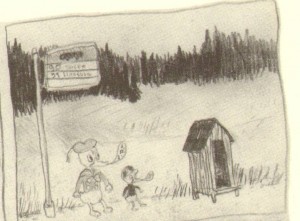

The younger child leaves our heroine crying and rides her bike back into the setting of the original sequence (with Donald duck and the brontosaurus).

To make the narrative coherent, we have to account for that shift in perspective.

There’s a double meaning in the title of this book that admittedly is a little weak in translation. The baba of the original title is an Italian pastry shaped like the buns in the bun field, but it’s also the way a baby says “baby.” In English, you’ve got to come up with “bun in the oven” before it starts to hang together.

A Google search for “Finnish bun metaphor” adds an additional image: “eating a dry bun” is something like “a hard pill to swallow.”

The coherence of the narrative – the scene in the bun field – hinges on this cluster of metaphors: the bun is a symbol for early childhood, plowing the field destroys (eats up) the buns, the loss of childhood innocence is “a hard pill to swallow” but an inescapable part of growing up.

The moment in childhood that the book’s narrative represents marks the collision of the affectionate, imagination-rich world of the young child, where animals drive cars and talk, with the colder, crueler, more violent adult world that the older child is becoming aware of – an awareness symbolized by the acquisition of the canine incisor.

That’s why the trigger for the sobbing is not her realizing that she’s killing the buns, but the younger child telling her she could “come home,” that “everybody was waiting” for her.

In the initial readings, the tears were trauma from the inescapable nightmare, or guilt and impotence over this “murder” she was forced to commit, and the younger child was an anomaly. Here they are tears of grief over the loss of that innocent perspective of childhood, over the fact that she really can’t return home to that beautiful place where the younger child still lives with the smiling dinosaur.

That’s a pretty coherent narrative, really. It’s a fully symbolic narrative, it isn’t transparently obvious or even particularly readily accessible, and I make no claims that it’s the only possible coherent narrative in the book – but it is coherent. What it isn’t, as Bart Beaty points out, is a “story.”

________________________________________________

Erica commented that “men write men’s stories.” The obvious corollary to this, which came up in other comments and threads, is that women write women’s stories. Erica’s point, though, is that both women and men end up writing men’s stories, men because they’re interested and women because they have to. But if this book isn’t a story, then it can’t really be a man’s story or a woman’s story in any obvious way.

I thought it might be helpful to see a piece of writing that was more obviously a “man’s” take on these themes – the casual cruelty of the grown-up world and the lack of control that naïve children have over their interaction with that world. I asked my well-read-in-comics friend Christopher Keels for an example (Thanks, Chris!), and while nothing set in early childhood came to mind, one selection stood out as a useful contrast. Josh Simmons’ Wholesome, from Kramer’s Ergot 4, also features a world-wise dog and the broad themes of cruelty and vulnerability/control, but the dominant emotion in Wholesome is anger.

Anger is aggressive and grief is passive, so in the most reductive, Pythagorean-opposites type of gender analysis I could say that based on these associations, Vähäm?ki’s book is feminine and Simmons’ story masculine. The comparison with Simmons certainly makes Vähäm?ki’s book feel more feminine than it does on its own, but there isn’t an equivalency. Simmons’ book feels more masculine than Vähäm?ki’s does feminine.

But Erica’s point is that women have to either mime male voices or accept a lower standing, and while it’s debatable whether the feminine perspective is important for reading this book, I can’t find a reading where Vähäm?ki’s miming an explicitly male voice. She privileges neither women nor men – we all experience childhood innocence and we all experience cruelty and grief. The main character is so neutral that Bart Beaty actually got the gender wrong (the English translation identifies her as a girl in the bar scene.)

“Stories” tend to work by invoking ideas and actions and relationships that are deeply embedded within a culture; stories have histories of their own independent of the specific manifestation of them in any given book. In many ways, “story” performs the same function in plot-driven fiction (like most genre) that “metaphor” performs in The Bun Field – it’s the thing that you have to recognize in order to tie the whole thing together and make it make sense.

So thinking about Erica’s point in light of Vähäm?ki’s work raises the question of whether metaphor takes on gender characteristics in the same way that story does – do “women’s metaphors” and “men’s metaphors” exist and work in the same way that men and women’s stories do? I think you have to answer that to determine whether any difference is made by the fact that The Bun Field was written by a woman.

It isn’t really a question that can be answered for myself by reading one book, though. I’ll just have to read some more art comics by women.

Next up: Renee French