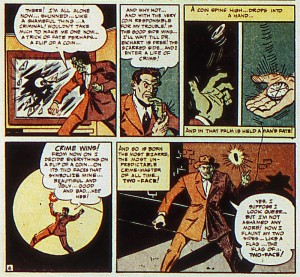

Bob Kane first drew the villain Two-Face in 1942 (Detective Comics #66). But it wasn’t till 2008 that the Nolan brothers got his origin right. My favorite scene from The Dark Knight is Heath Ledger’s Joker convincing Aaron Eckhart’s brutally disfigured Harvey Dent to embrace the dark side. How’s he do it?

With the flip of a coin.

Javier Bardem made similar use of a quarter the year before in the Coens’ No Country for Old Men. Live or die? Ask JFK and the eagle.

Rewind two more years, to Woody Allen’s 2005 Match Point, and Jonathan Rhys Meyers spells it out: “People are afraid to face how great a part of life is dependent on luck. It’s scary to think so much is out of one’s control.”

Meyers’ character (he later gets away with murdering an inconvenient lover) fascinated Roger Ebert because, like all of the characters in the film, he’s rotten: “This is a thriller not about good versus evil, but about various species of evil engaged in a struggle for survival of the fittest — or, as the movie makes clear, the luckiest.”

Bardem’s Anton Chigurh is a hitman, so at least he’s supposed to kill people. But that’s not what makes him so damn scary. The movie’s nihilism is contained in those coin flips. When Chigurh tells a gas attendant to “Call it,” the man says he didn’t put nothing up to bet. “Yes, you did,” Chigurh answers. “You’ve been putting it up your whole life you just didn’t know it.”

Myers’ tennis pro plays the same game: “There are moments in a match when the ball hits the top of the net, and for a split second, it can either go forward or fall back. With a little luck, it goes forward, and you win. Or maybe it doesn’t, and you lose.” Near the film’s end, when he tosses an incriminating piece of evidence (his dead lover’s ring) toward the river, it takes the same fate-determining bounce. He wins.

When the gas attendant wins his toss, Chigurh congratulates him and tells him not to put the lucky quarter in his pocket where “it’ll get mixed in with the others and become just a coin. Which it is.” Chigurh’s last victim already know this and so refuses to play: “The coin don’t have no say. It’s just you.”

“Well,” says Chigurh, “I got here the same way the coin did.”

The Nolans’ Joker embodies the same anarchic philosophy: “I’m not a schemer. I try to show the schemers how pathetic their attempts to control things really are.” And in the true spirit of anarchy, he points the gun at himself. “I’m an agent of chaos,” he explains to Harvey Dent as he leans his forehead into the barrel. “Oh and you know the thing about chaos, it’s fair.”

The Joker survives his coin toss too, but not Dent. He’s Two-Face now. He worships Chigurh’s god.

My wife and I were recently catching up on the last season of the British cop show Luther. It opens with Idris Elba (we liked him as a gangster in The Wire too) sitting on a couch, playing Russian roulette. He learned the game from a homicidal army vet, not the Joker, but his character is relinquishing his will to the same higher Non-Will as the others. Except Luther is a (mostly) good guy. So by the season’s end he’s traded in the gun (he rarely carries one anyway) for an ice cream cone with his newly adopted teen daughter. What got him there?

Not a coin toss.

It wasn’t a roll of the dice either. That’s the device of chance preferred by the season’s ugliest villains, a pair of identical twins (two people, one face) playing a real-world game of D&D. They earn experience points by killing people. You can do it anywhere, a gas station, subway, a lane of stopped traffic. Just open your backpack, spread out your bat, hammer, and squirt gun of acid, and roll the dice.

I bought our twelve-year-old his first D&D game this Christmas. (He learned about the game last year from a particularly hilarious episode of our family’s favorite sitcom, Community.) So while Luther’s evil twins were rolling their dice, our son was upstairs rolling his. I can now differentiate between the thump and skid of dice on floorboards and the smack and skitter of dice in a D&D box lid.

I asked him once, if instead of killing the various trolls and orcs and armored whatnots he has to battle, could he just knock them out, tie them up, and leave them for the authorities to incarcerate?

He said, “What authorities?”

Right. There’s no government in D&D. It’s literal anarchy. Even at the metaphysical level. There are plenty of supernatural beings, but no Supreme One. Gods but no God. Even the Judeo-Christian Lord is only the sum of the numbers in the Dungeon Master’s hand. And the DM isn’t God either. He (yes, in this case, DMs are almost as uniformly male as Catholic priests) must obey the Dice like everyone else.

Roll them to determine the whims of heredity, what skills and proclivities you’re born with, which you’re not. The Dice control every important moment of your life, every struggle, the literal blows of chance. Sure, my son admits to ignoring the occasional bad roll, but he said it gets boring if you do that too much. Real life is random.

So why is randomness overwhelming portrayed as “evil” in pop culture?

First time I saw Two-Face as a kid (October 1976, The Brave and the Bold #130), he bewildered me. Instead of just killing Batman and Green Arrow, he and the Joker flip a coin? (Allowing the Atom to secretly climb on and alter its fall.) At some point in the story, Two-Face betrays the Joker—and not because Heath Ledger killed his fiancé. It’s just what his quarter tells him to do. So why, my ten-year-old self wondered, is the guy considered a supervillain?

When those D&D twins bend down with a 20-sided die, only the ugliest options are in play. Shouldn’t your backpack have more than murder weapons? Where’s the wad of twenties for homeless people’s cups? Why does Chigurh only flip a coin when he’s thinking about plugging someone in the head? A true worshipper of chance would be Mother Theresa half the time.

So it’s not randomness that makes hitmen, supervillains, D&D players, and tennis pros scary. It’s the deification of randomness. The abdication of responsibility. A true nihilist (like Alan Moore’s Comedian) embraces the absence of God and so the permissibility of everything. But that’s an abyss too deep for the Two-Faces of the world. They can’t fill that God-sized gap with themselves. They can’t hack that much free will. So instead of randomness, they invent Randomness and pretend they’re just following order. Pretend that’s not really your finger on the trigger.

You can take comfort in the illusion that the bullet in Russian roulette chooses you. But an ice cream cone, that’s something you have to go out and get. It’s a scheme. You have to choose to want it despite the uncontrollable probabilities of your getting or not getting it. If life’s a crap shoot, the only question is how you cope with that fact.

I do know one writer who flips Randomness to make us see it not as a force of evil but of good. Or, more accurately, of helpful change. Glen Dahlgren’s A Child of Chaos spins a D&D-inspired world where the lazy gods of Charity, Evil, War, etc. have gotten a bit too complacent. What the universe needs is the smack and skid of a die. Literally. That’s the magic instrument of Chaos, how the promised one will restore some much needed disorder, unlock all that magic the privileged class keeps hogging. No more homicidal lunatics. Chaos is our hero.

Unfortunately you don’t get to read Dahlgren’s novel yet. My copy is a Word file in my laptop. The manuscript (like my own third novel) is still mid-spin in the seemingly random universe of the publishing industry. I’m rooting for the unmarred JFK side of the coin. But there are no guarantees. Right now my agent is battling the forces of Evil and trying to land my manuscript in a New York house. It’s a chaotic process (stalled by the randomness of a hurricane and jaw surgery so far), but the dice keep bouncing.

Glen and I aren’t complaining. Like Chigurh’s last victim, we understand the rules of the game: “I knowed you was crazy when I saw you sitting there. I knowed exactly what was in store for me.”

God bless chaos.