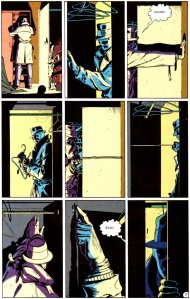

I read the first issue of Watchmen while it was still on comic shop shelves back in 1986. Though “read” is the wrong word. A total of three words appear on pages five, six, seven, and eight. No captions. No thought bubbles. No dialogue. Just Rorschach mumbling “Hunh,” “Ehh,” and, my favorite, “Hurm” to himself as he investigates a crime scene. The action is cerebral. No heroes and villains exchanging punches and power blasts. Rorschach notices that the murder victim’s closet is oddly shallow, and then bends a coat hanger to measure it against the depth of the adjacent wall. A further search reveals a secret button, and then a hidden compartment, complete with (SPOILER ALERT!) the Comedian’s superhero costume.

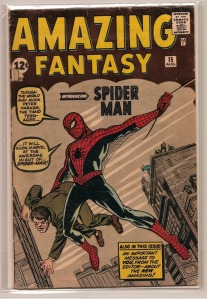

That’s just nine panels of Gibson and Moore’s unnarrated 31-panel sequence. I’d never “read” anything like it. Not that Moore had anything against the English language. Look at the pages right before and after the silent sequence. 198 and 199 words each. When chatting, the Watchmen are as wordy as Spider-Man in his 1962 debut. Open Amazing Fantasy #15 and the first two pages clock in at 196 and 234 words each.

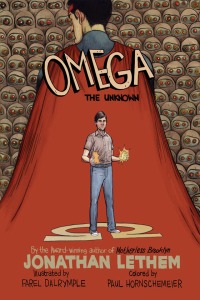

Not many letters shook loose in the leap from Silver to Bronze Age. Take a couple of pages from my personal ur-comic, The Defenders #15 of 1974, and you get 232 and 169. When Omega the Unknown debuted two years later, wordage had shrunk only a little, with pages of 156 and (I hope you realize how annoying it is to count these) 177.

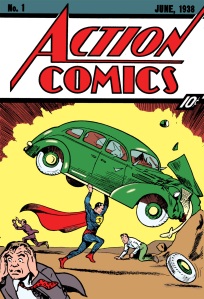

But now fly back to the Golden Age. Scan Action Comics #1, and the 1938 Superman only muscles out 94 and 95 words. The mean skyrockets if you average in Jerry Siegel’s two-page prose story in the back Superman #1, but DC was only placating some now obscure publishing requirement. Marvel included a similar experiment in 1975, dropping single pages of prose into Defenders episodes (the improbably advanced vocabulary included “vacuous,” “belie,” and “veritable.”) My nine-year-old eyes barely skimmed them.

Despite varying word counts, the maximum for a dialogue-heavy panel remains about the same through the decades. Clark and his Daily Star boss cram in 30 words. Same number as the more talkative Omega panels. Peter Parker’s would-be manager leans over him with a 38-word speech bubble. And the cops investigating the Comedian’s death spit out some 35 words per panel too. So dialogue is the comic book’s universal constant. Moore didn’t mess with that. When talking, his characters sound like everybody else. The difference is when they shut up.

Before the mid-eighties, comic books were written in an omniscient third person voice. Those pages of prose in 1975 weren’t a freakish contradiction. They were the culmination of the industry’s style, the medium’s secret default setting. The background hum of talk. The author just couldn’t keep his mouth closed. It was as if he didn’t trust all those vacuous little pictures not to belie his veritable story.

“It takes a very sophisticated writer of long experience and dedication,” Will Eisner explains, “to accept the total castration of his words, as, for example, a series of exquisitely written balloons that are discarded in favor of an equally exquisite pantomime.”

There was a lot of castration anxiety from early comic book writers. Jerry Siegel’s Superman captions read like instructions to artist Joe Shuster: “With a sharp snap the blade breaks upon Superman’s tough skin!” Bill Finger’s Batman captions distrust Bob Kane’s pen even more: “The ‘Bat-Man’ lashes out with a terrific right . . . He grabs his second adversary in a deadly headlock . . . and with a might heave . . . sends the burly criminal flying through space.”

Two decades later and Spider-Man was just as redundant: “Wrapped in his own thoughts, Peter doesn’t hear the auto which narrowly misses him, until the last instant! And then, unnoticed by the riders, he unthinkingly leaps to safety—but what a leap it is!” Steve Ditko and Stan Lee tell the core of the origin—the radioactive spider bite—in three panels, speechless but for Peter’s “Ow!” But those three captions cram in 112 words.

Lee understood the complexity of visual story-telling. (The original Amazing Fantasy art boards include his margin note: “Steve—make this a closed sedan. No arms showing. Don’t imply wreckless driving—S.”) But comic book convention mandated narration, regardless of redundancy. Even when working without a script, Ditko covered his pages in empty captions and talk bubbles for Lee to fill in later. In Amazing Spider-Man #1, Spider-Man webs a rocket capsule as it flies past the plane he’s balancing on. The panels are visually self-explanatory, but words were still required. Instead of narrated captions, it’s Spider-Man pointlessly announcing “I hit it!” and “Mustn’t let go!” and “I reached it! But now . . .”

Alan Moore trusted pictures. When captions appear in Watchmen, they contain character speech, usually juxtaposed from a previous panel. When characters stop talking, the frame is silent. Nobody is chattering in a box overhead. The murder victim in the first issue isn’t the Comedian. It’s the narrator.

Unlike most deaths in comic books, this one was permanent. When Jonathan Lethem and Karl Rusnak created a new Omega the Unknown in 2008, they opened with two pages of wordless panels. Although Rusnak says Steve Gerber, the original writer, “raised the since out-of-favor device of caption narration to an art form,” Lethem still “wasn’t interested in captioning—in fact I wanted to mostly work without it.”

That goes for most creators today. Look at Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s All-Star Superman. Look at Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Bagley’s Ultimate Spider-Man. Look at Robert Kirkman and Tony Moore’s The Walking Dead. It’s not just the word counts that changed. Words count differently.