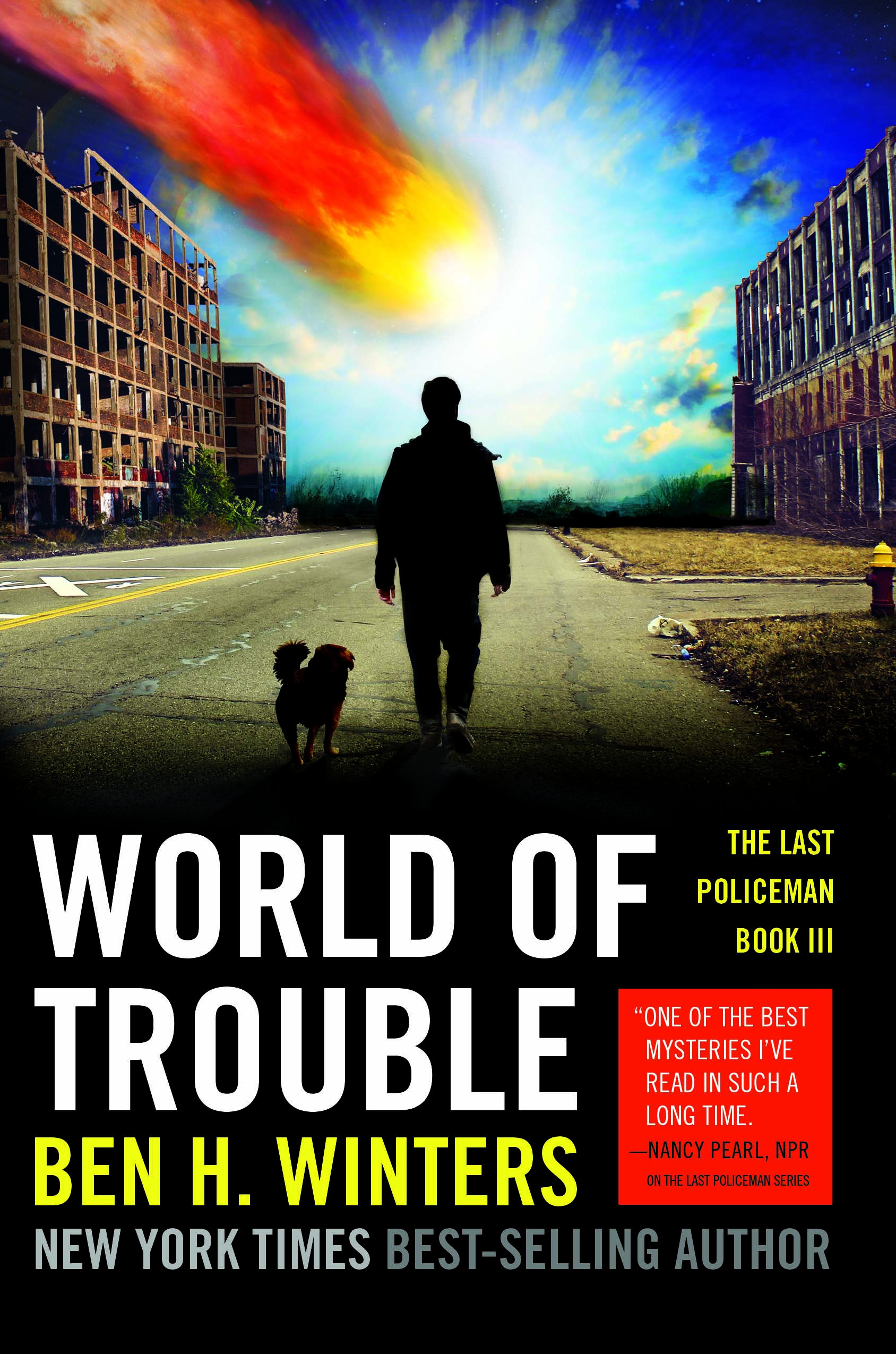

My cousin Ben H. Winters wrote to ask me to contribute to his reverse blog event timed to coincide with the release of the third novel in his Last Policeman series, World of Trouble. The book is a sci-fi detective genre bending mas-up about tracking down murderers at the end of the world.

As that description indicates, Ben’s novel crosses genres, and he saw a bit of a parallel with my criticism, since I write about lots of different genres (YA, and comics, and sci-fi, and literature, and romance, to just stick to print ones.) And, for that matter, for a blog that’s ostensibly about comics, HU is quite eclectic when it comes to what genres we cover. We have posts on wine, posts on fashion, posts on film and posts on music, just for starters.

So, Ben asked me, what’s with that, exactly? Are there benefits to crossing genres? Or does it just sow confusion?

The answer is maybe some of both. There are definitely disadvantages to eclecticism. The main downside is that aesthetic experience in our culture is organized, often quite intensely, around genres. Lots of folks of course have different genre interests — but nonetheless, if you go to a comics website, you tend to want to read about comics, not fashion or music or wine. So just in terms of marketing and retaining an audience, crossing genres as often as we do at HU can be a bad idea. You confuse the brand.

Crossing genres can also be uncomfortable in other ways. Genres aren’t just category designations; they’re communities. Refusing to embrace one genre means to some degree that you’re refusing to fully occupy one community — and that means people can end up seeing you as untrustworthy or as an interloper. I’m interested in romance novels and comics, for example, but I’m not exactly in the fandom of either, which means I haven’t necessarily read as much as people who are more fully committed. I’ve had both comics fans and romance novel fans be super-welcoming, and interested in what I have to say. But I’ve also had people from both communities basically argue that I don’t have enough expertise to speak, or that I’m morally compromised when I talk about the genres because I’m an outsider.

I don’t mean to dismiss those critiques. It can be difficult, or uncomfortable, or problematic, to write as an (at least partial) interloper. Just as it can seem needlessly alienating, I suppose. to write fashion posts on a comics blog. Still, I think it’s worth doing both for a couple of reasons.

First, I get bored writing about the same thing all the time. I like many comics, and I like many romance novels, but I don’t want to just read and write about comics, or just read and write about romance novels. I doubt that that’s especially unusual or anything — most people have different interests and like to dabble in different things to some extent. But fear of boredom is a big part of the impetus for me to try new things and write about new things, so I thought I should mention it.

The second reason is a little more involved. Maybe I can explain best through a book by Carl Freedman called “Critical Theory and Science Fiction.” In the book, Freedman points out that while we usually think of art being broken down into genre, it’s actually more accurate to say that genre precedes, or defines art. Shakespeare’s plays, for example, are art. Shakespeare’s laundry lists are not art. The genre of plays are seen as aesthetic objects, worthy of analysis and fandom. The genre of laundry lists, not so much. Recognition of genre, then, precedes the perception of art. For art to be art, it needs to be in the right genre.

I think this is true beyond just laundry lists and plays. Freedman points out that sci-fi, by virtue of its genre, has often been seen as lesser or marginal — Samuel Delany’s novels aren’t laundry lists, but they’re not quite perceived in the same ways as (say) Borges’ stories either. Romance novels are even more denigrated. Wine often isn’t exactly seen as an aesthetic experience at all — or at least not as one that can be usefully discussed alongside film or television or literature.

The question here might be, so what? Why does it matter if people want to think about comics rather than fashion, or literature rather than romance novels?

Sometimes, maybe it doesn’t matter all that much. But, as genres are social constructions, the way they’re manipulated can also have social effects, for better or ill. Freedman notes that African-American literature, for example, is often treated as a specialized genre, marginal to capital-L literature. Romance’s denigration has a lot to do with the way it is perceived as art by and for women — which is why fashion is often seen as not-quite-art as well. Genre designations tell us what is important, what has quality, what is of interest. And they do so in a way that is often beyond analysis, because the recognition of, or use of, genre, precedes, and creates the grounds of, the analysis itself.

Which is why I’m interested in trying to engage with different genres, and to think about the ways (for example) in which comics fandoms and romance fandoms are similar and different, or to include posts about video games alongside posts on Trollope. Genre shapes how we look at art, and so at life. That’s not a bad thing, necessarily— but it seems worth shaking it up occasionally too, if only to see who’s being left out of which landscapes. As in Ben’s books, a different investigator can maybe help you see where the world ends, and where others might start.

____

A slightly edited version of this, complete with significantly more amusing illustration captions, is cross-posted over at Ben’s blog. Variant blog posts for completeists!