When last we met, dear reader, Uncle Toby had just begun, at long last and after much prefatory hemming and hawing, to describe to the Widow Wadman where exactly he had been wounded in the Siege of Namur. 1 To recap:

Part 1: The centre of superhero comics is the fight scene — a sequence of events caused by the aggressive and defensive (and other) actions of two or more combatants

Part 2: This constrains the range of all of the possible superpowers into the very limited dimensions we see in most superhero comics — viz. powers of touching and hurting, and not-being-touched and not-being-hurt

Part 3: You’re reading it now. The calls are coming from inside the house.

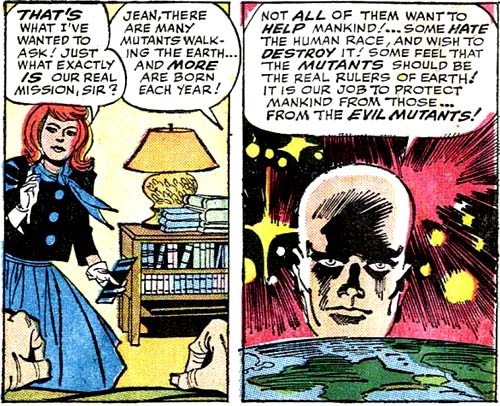

And so we come, at last, to Jack Kirby and the X-Men.

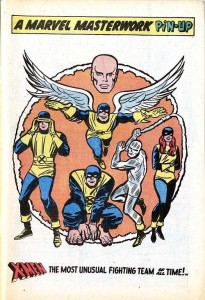

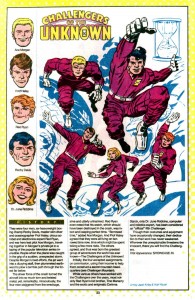

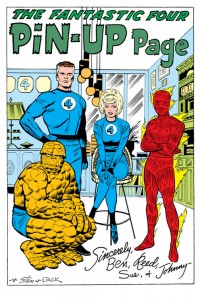

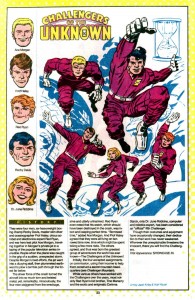

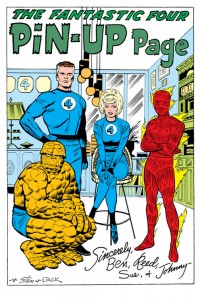

The X-Men were, by my count, the third group of heroes Jack Kirby created or co-created that all wore the same costume — first the Challengers of the Unknown in 1958, then the Fantastic Four in 1961, and the X-Men in 1963. It’s an interesting design decision, and it tends to occur only in groups that are created (as it were) whole cloth. You don’t generally find team uniforms in groups like the Avengers or the Justice League of America — unlike the X-Men or Fantastic Four, who first appeared as a group, guys like (say) Batman or Thor already have their own costumes from their own previous appearances.

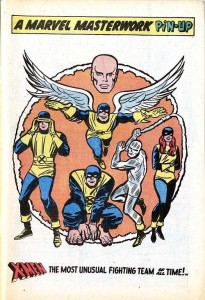

A shared uniform makes things easy for the artist in one sense — there’s just one basic costume to design. But it makes things harder as well, precisely because the artist can’t distinguish one character from another with different costumes. The only way to distinguish characters in uniform — particularly when a mask is part of the uniform, as with the X-Men — is through body-type or minor costume flourishes.

Kirby failed on this front with the Challengers of the Unknown; other than the fact that one of them is a punchy tough guy type, who can remember anything whatsoever about the individual Challengers? But he learned his lesson and made sure to distinguish the Fantastic Four and X-Men more strongly. So in the X-Men, you’ve got: a guy with a visor, a guy who transforms into a kind of snowman, a stocky guy, a guy with wings, and the girl (sic). The designs are simple but effective; you can easily tell at a glance who’s who. (In the decades since, later X-Men artists have variously abandoned and reintroduced the uniforms in one form or another.)

In their shared uniform, then, the X-Men appeared as part of that first wave of Marvel characters from 1961-1965 or so. It’s by now a truism — repeated countless times by Stan Lee, who created every single one of those characters 2 — that what distinguished those dynamic superheroes from their more staid counterparts at DC, was that they had “real problems”. These problems were generally either psychological — the abiding survivor’s guilt of Spider-Man and (once he was reintroduced from the 1950s) Captain America; interpersonal — the Avengers and Fantastic Four were always bickering; or, most relevantly here, physical. Thus Thor’s alter ego was lame (sic), Daredevil was blind, Iron Man needed constant medical care through his armour, the Hulk couldn’t control his transformations, the Thing was trapped in his monstrous form, Dr Strange had his hands mangled in a car accident, and even Nick Fury, in his then-contemporary role as agent of S.H.I.E.L.D 3, wore an eyepatch. 4

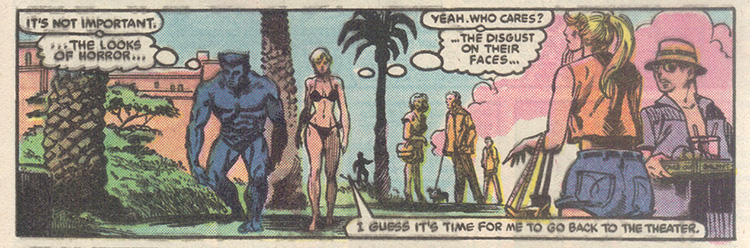

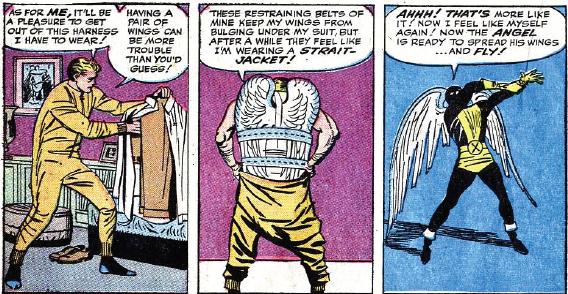

So too with the X-Men: Angel’s wings made him unable to “pass” as a regular human (to a lesser extent, Beast suffered the same thing with his oversized hands and feet); Cyclops couldn’t control his laser-beam eyes, so he had to wear either his visor or special glasses at all times; and of course their leader and surrogate father, Professor X, was a paraplegic.

Fittingly for characters with such overtly physical disability, those same disabilities were also balanced by other superhuman ways of moving, touching, and not being touched. And those, of course, are the very same dimensions we saw in Part 2 of this essay, as the necessary foci of a genre devoted above all else to the fight scene (as discussed in Part 1). These foci are not unique to the Marvel comics of that period, of course; certainly at DC there were also characters, at roughly the same time, that were based specifically on ways of moving — most notably Hawkman and the Flash.

Now, how could moving be a requirement of fight scenes, if fight scenes are all about touching and hurting? Answer: moving is one of the best ways of not being touched — to fly away, or run away, or bounce around to dodge your foe 5. And the ne plus ultra of moving and touching is Kirby’s X-Men.

***

Even though they’d later form the basis for one of Marvel’s biggest cash-cows, these comics are nobody’s favourite Kirby comics 6; the King stopped drawing after just eleven issues (although he continued to provide layouts for other artists to complete), and most of the villains are eminently forgettable. But they do contain Kirby’s most distilled expression of these core elements of moving, not moving, touching and not being touched, hurting and not being hurt.

Take a look at the cover of their very first issue:

Cyclops and Ice-Man try to touch Magneto through action-at-a-distance; the Beast swings in on what looks like a circus trapeze; and the Angel uses his one and only power, to fly…with a bazooka. Naturally Marvel Girl — being, you know, a girl — can’t do anything except cower in the background.7

And what effect do these attacks have on their target? None, because Magneto uses his powers not to be touched.

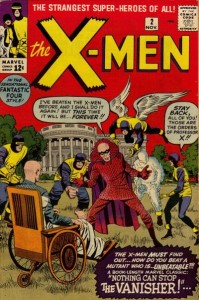

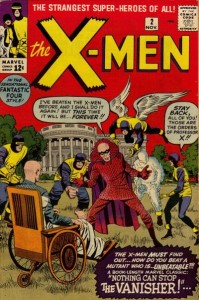

Issue 2 sees the X-Men facing this guy:

whose one and only power is teleportation. He’s unbeatable, as per the caption, because he can’t be touched — he just moves away by teleporting somewhere else.

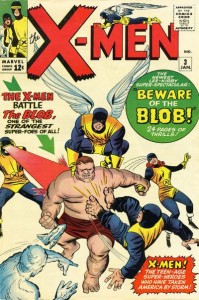

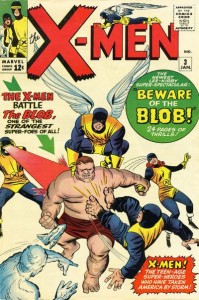

In Issue #3, they face the Blob, whose pudgy flesh absorb all attacks, and who cannot be budged unwillingly. Touching is ineffective and he cannot be moved.

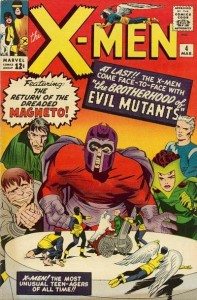

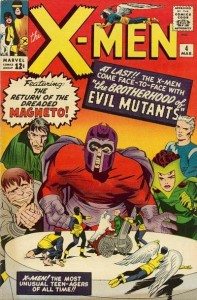

Issue #4 introduces Magneto’s own team, the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, comprising: head honcho Magneto, a ranting megalomaniac; obsequious sycophant, Toad; siblings and reluctant recruits Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch; and supreme creep Mastermind — whose costume, incidentally, is basically that he looks like a sex offender. I mean, look at this guy 8:

Of these new characters in the Brother(sic)hood, two are based on ways of moving — Toad, who jumps around like his namesake, and the super-fast Quicksilver.

Kirby must have liked drawing the Brotherhood (or else had no better ideas for villains), because they reappear in #5, #6 (allied with Bill Everett’s creation, the Sub-Mariner — a swimmer and flier both) and #7 (allied this time with the Blob).

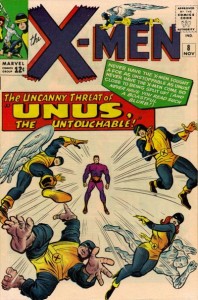

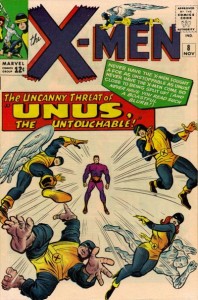

# 8 sees the X-Men facing Unus the Untouchable.

‘Nuff said

In #9, we learn how Professor X lost the use of his legs the first time around. (He’s regained and lost their use at least four times since then. 9)

#10 and #11 give us a break from the motifs. #10 reintroduces Ka-Zar, a — well, calling him a “character” is probably too generous, but — a character from the musty Marvel vaults of the 1930s, a risibly blatant Tarzan rip-off — actually, make that just plain risible. And #11 gives us the Stranger, an otherwise forgettable antagonist whose only point of interest is as a precursor to Kirby’s many later space gods. 10

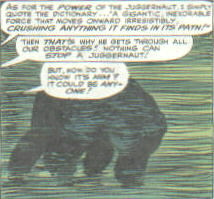

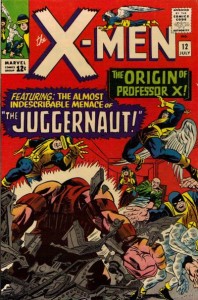

#11 was Kirby’s last issue as primary artist, although he continued to contribute layouts, and covers, until #17. But I want to discuss one more of these early issues, indeed, the first issue he didn’t provide the complete art for — #12. Because this issue, with finished art by Alex Toth and Vince Colletta, introduces one of the seminal moving/touching/hurting characters in X-Men, the supervillain called the Juggernaut. 11

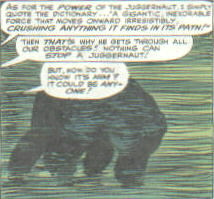

The Juggernaut is the step-brother of Professor X — which fact, all by itself, sets us up to expect some kind of contrast with Xavier’s paraplegia. And the Juggernaut doesn’t disappoint:

As for the power of the Juggernaut, I simply quote the dictionary…’A gigantic, inexorable force that moves onward irresistibly crushing anything it finds in its path!’

The Juggernaut’s power is unstoppability, in the most literal, kinetic sense. Once set on a path, he cannot be stopped or turned aside. Indeed, #11 itself embodies this concept. The issue starts with the blare of a warning alarm, signalling their “most deadly threat!” Xavier orders the team to fortify the school using their powers; Iceman makes an ice wall, and Cyclops blasts a trench which the others further strengthen. The Professor then talks us through a flashback into his history with the Juggernaut, which is repeatedly interrupted by the sound of the Juggernaut breaking through each of the school’s defences, one by one. All this time, the Juggernaut remains unseen except in fragments or through smoke, until on the final page he breaks through the final defence and appears unobscured in the very last panel.

He moves, he moves, and he moves, and nobody can stop him.

***

Now: I’m not trying to say that any of this is unique, that only the X-Men has this focus on moving/touching/hurting//not-moving/not-being-touched/not-being-hurt. On the contrary, it’s the basis of the whole genre. But I do think that it appears in its purest, most distilled form in those first dozen issues; villains who move, who can’t be stopped, who can’t be touched, they’re the greatest threat to these early X-Men.

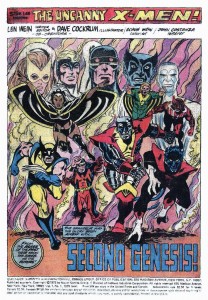

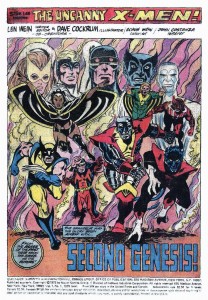

Although Kirby and Lee created the original X-Men, the title was not a hit and struggled to maintain an audience. Sure, sure, it distilled the form, blah blah blah but take another look at those villains up there — hardly Kirby’s finest hour. No, X-Men only grew into success after Len Wein and Dave Cockrum relaunched the series in the mid-70s, replacing almost all of the cast with a slate of new characters; and, almost immediately after that relaunch, Wein was replaced by Chris Claremont, who — along with Cockrum and John Byrne — deserves, essentially, all of the credit for the X-Men’s later, massive popularity. Claremont wrote X-Men (later renamed Uncanny X-Men) for seventeen years, an exceedingly unusually long stretch for that kind of comic (i.e. a superhero comic published and owned by Marvel or DC), especially given that, along the way, he co-created and wrote various spin-offs for several dozen issues.

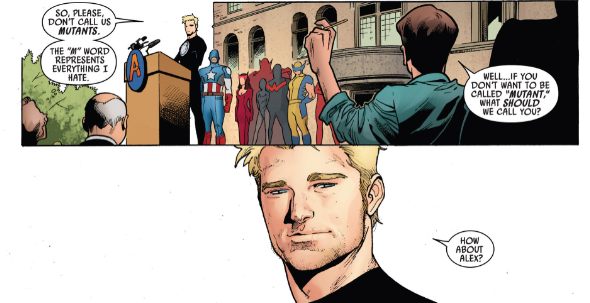

The standard reading of Claremont’s (and his successors’) X-Men is as metaphor for civil rights and minority oppression, a reading that’s actively encouraged at times by Claremont himself (e.g. the “graphic novel” God Loves, Man Kills, or the Holocaust backstory he gave to Magneto).

The main problem with this reading is that it’s stupid. Being (say) African-American, or gay, generally doesn’t mean you can shoot laser beams out of your eyes. (Unless there’s something the NAACP hasn’t been telling the rest of us all these years.)

The real “meaning” of the X-Men comics by Claremont et al. is metaphor for adolescence — or, rather, for the adolescent’s self-mythologizing about the experience of adolescence. Mutants are the “children” of humanity, who “hate and fear” them for being different. The reason mutants are ostracised by society at large, the reason that society considers them freakish and dangerous, is most definitely not because that society considers them inferior, degenerate, sub-human. On the contrary, it’s because of their special, unique powers — which typically emerge only in puberty(!) — that set them above the average human; a conceit of the series is that mutants form a new “species” called Homo superior.12 The X-Men aren’t a symbol for the oppressed, they’re a symbol for teenagers who think they’re oppressed.

On top of this basic metaphoric structure that he gradually engineered for the series, Claremont further added his distinctive emo-avant-la-lettre scripting and histrionics; with the X-Men, just as with every teenager everywhere, it’s always, literally, The End Of The World. No wonder the whole thing became so titanically popular, it’s YA in extra-large capitals.

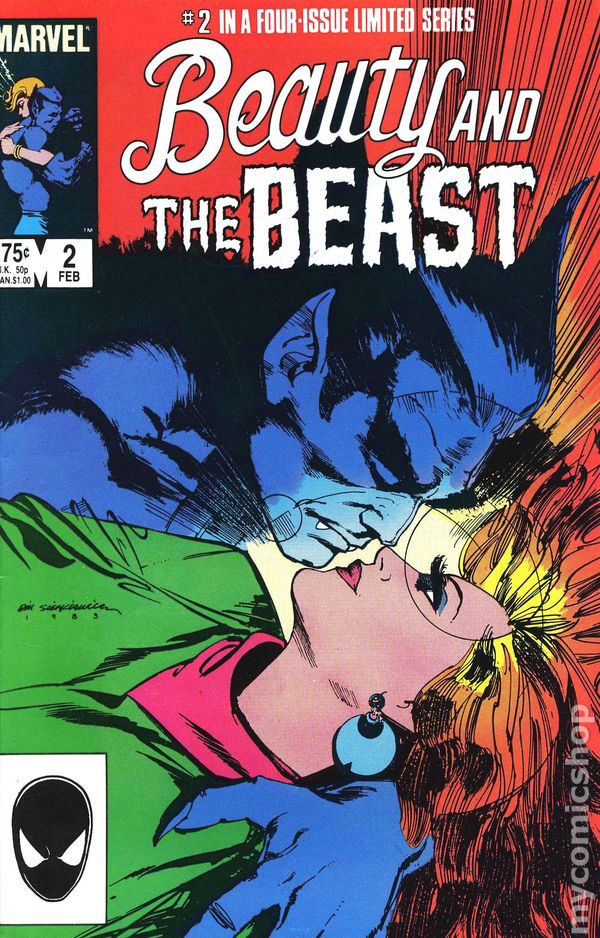

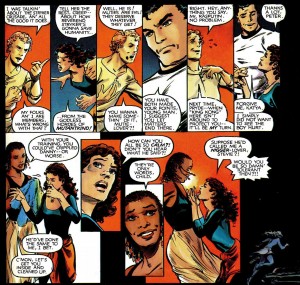

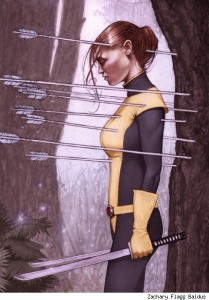

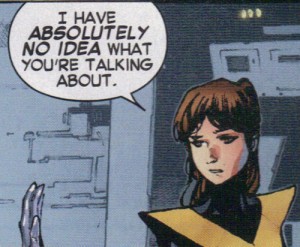

I’ll close, then, by pointing out how well Claremont understood the importance of touching/moving/hurting. For these were things that Claremont would return to, again and again, over his seventeen-year tenure. In particular, the motifs of touching and not-being-touched form the basis for his two most popular co-creations, Kitty Pryde and Rogue. 13

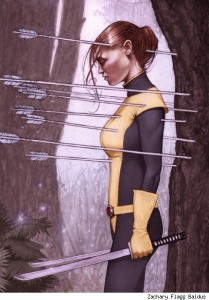

Kitty Pryde’s power is to turn herself into a kind of living ghost — a person with no solidity, who can walk through walls, through whom bullets and punches pass without damage or so much as contact. She cannot be hurt, because she cannot be touched.

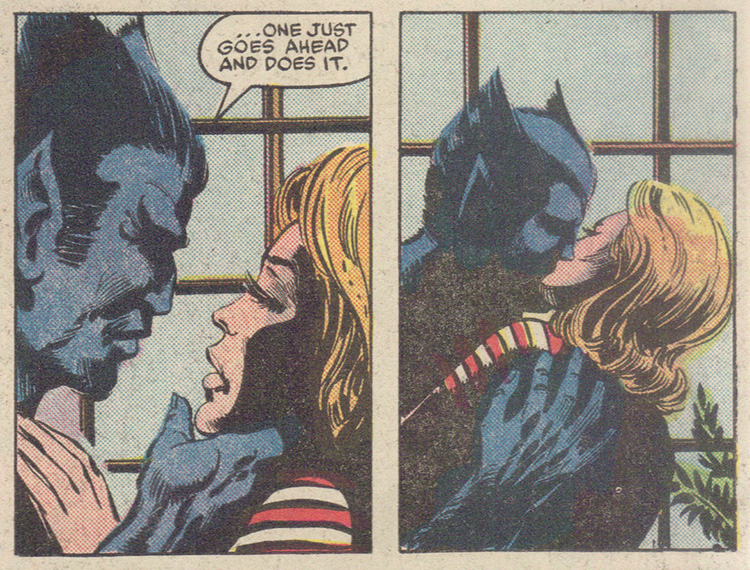

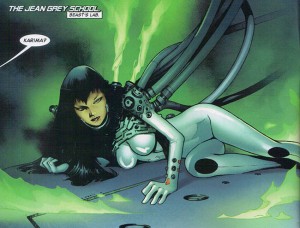

Rogue, on the other hand, must touch for her powers to work — when she touches anybody, she temporarily absorbs their superpowers and memories, and they (usually) lose consciousness. But, in a twist typical of the Earth’s Angstiest Heroes, her own power is as much curse as blessing; since she cannot control her power, since it works automatically and instantly, she *choke* can never know the touch of another.

Think about it: two of the most popular characters in the most popular superhero comic book in the 1980s were a girl who couldn’t be touched if she didn’t want to be, and a young woman who couldn’t touch someone, even if she wanted to, without causing them serious harm. This is where the planets aligned for Chris Claremont, Tom Orzechowski, et al. — where the structural necessity of moving/touching/hurting–not-moving/not-being-touched/not-being-hurt lined up perfectly with Claremont’s main themes of adolescent angst and self-mythologizing. For, if these powers exemplify a way of fighting, they also serve as potent metaphor for the experience of adolescence — at least for a certain kind of adolescent, the kind, say, that might be buying a superhero comic called Uncanny X-Men.

***

There’s a lot more that could be said here about this triad in Kirby, Claremont, or any number of other artists — e.g. Claremont (et al.’s) New Mutants, or Steve Ditko’s ectoplasmic excrudescences — but, really, the poet said it best when he wrote:

It feels good, when you know you’re down

A super dope homeboy from the Oak town

And I’m known as such

And this is a beat, uh, you can’t touch

I told you, homeboy

(You can’t touch this)

Hammer Time!

***

1.SPOILER: It was in Namur.

2.Relax, internet, I’m kidding.

3. Supreme Headquarters International Espionage Law-enforcement Division.

4. It’s suggestive that, alone amongst that first wave, Ant-Man/Giant-Man was beset by no such problems — and has been generally unable to sustain his own comic book for long.

5. That said, this utilitarian function isn’t the whole story; there is also the basic wish-fulfilment aspect of (say) flying, not to mention that it just gives the artist another bunch of cool stuff to draw when the characters can fly, or run really fast, or swing through the air, or whatever. And of course there’s also loads of outlandish vehicles that are used for transport rather than combat — the X-Men’s own Lockheed jet (introduced well after Kirby had left), Wonder Woman’s invisible plane, Thor’s goat-driven chariot, Spider-Man’s Spider-Mobile, the Black Racer’s skis…

6.*sigh* All right, internet, prove me wrong.

7. Like the question “Who tied up Mr Fantastic on Jack Kirby’s cover for Fantastic Four #1?” the question “What is Beast’s swing attached to?” admits of no definite answer. Also — what exactly does Angel think is going to happen to him when he fires that bazooka? Brace yourself, son.

8. And he would later become pretty a sex offender for real, in the hands of Chris Claremont and John Byrne. The image here is by Byrne and Terry Austin.

9. When he was cloned by the Shi’ar, after he was nearly assassinated by Stryfe, when Xorn healed him, and after House of M. And, no, I haven’t actually read all of the comics in question because jesus christ are you out of your mind?

10. The Stranger can fly and walk through walls, but these are small potatoes compared to his overall cosmic powers

11. There are at least two mind-boggling things about this collaboration — first, Toth pencilling over somebody else’s layouts, and, second, Toth being inked by Colletta. One imagines that Toth did not altogether appreciate the experience — although Colletta might have, since he wouldn’t have to erase as many lines with Toth.

12. This conceit doesn’t make a whole lot of sense; mutants wouldn’t count as a new species on any biological account of what makes a species (or, at least, any account I know of). Superhero comic book uses dubious science — stop the press.

13. As evidence for their popularity, see this 2011 poll at Comics Should Be Good of the Top 100 Marvel Comic Book Characters. CSBG is a generally reliable barometer of superhero fan opinion, and this poll ranked Kitty Pryde as #19 and Rogue as #23. Emma Frost is the only Claremont co-creation to rank higher, at #17, but much of that popularity is due to her reinvention by Grant Morrison, who gave her a new power, to turn into a super-tough, hard-to-hurt diamond form.

CREATOR CREDITS: Part 1 — Superman, Lex Luthor and Metropolis created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster; Brainiac created by Al Plastino and Otto Binder; Thor, Loki and Asgard created by Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and Larry Lieber; Captain America created by Kirby and Joe Simon; the Hulk, Absorbing Man, Odin, the Avengers, Batroc zee Leapair created by Kirby and Lee; the Justice League of America created by Mike Sekowsky and Gardner Fox; Batman created by Bill Finger “and Bob Kane”; the Joker created by Jerry Robinson, Finger, “and Bob Kane”.

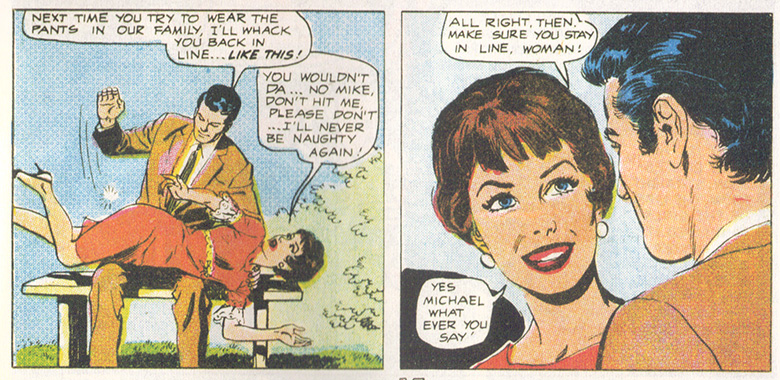

Part 2 — Dr Strange and Spider-Man created by Steve Ditko and Lee; Iron Man created by Don Heck, Kirby, Lee and Lieber; the Fantastic Four created by Kirby and Lee; Thulk, Wulk, Fwulk, Cfwulk, Rcfwulk, Rulk, Chulk and Dchulk created by Jones, one of the Jones boys; Doom Patrol created by Bruno Premiani and Arnold Drake; Brotherhood of Dada created by Richard Case and Grant Morrison; Nova created by John Buscema and Marv Wolfman; Captain Marvel created by Gene Colan and Roy Thomas; Superior and Ultimate Spider-Man created by, hell, let’s just say Ditko and Lee; Carnage created by Erik Larsen, Mark Bagley and David Michelinie; Venom created by Randy Schueller, Mike Zeck, Todd McFarlane and Michelinie; Scarlet Spider created by I couldn’t be bothered to decipher the wikipedia page; Morbius and Iron Fist created by Gil Kane and Thomas; Punisher created by Ross Andru, John Romita and Gerry Conway; Daredevil created by Bill Everett, Wally Wood and Stan Lee; Hawkeye created by Heck and Lee; Wolverine created by Romita, Herb Trimpe, and Len Wein; Gambit created by Jim Lee and Chris Claremont; Deadpool “created” by Rob Liefeld and Fabian Nicieza; Kick-Ass created by John Romita Jr and Mark Millar; Pandora created by Andy Kubert and Geoff Johns; Phantom Stranger created by Carmine Infantino and John Broome; John Constantine created by Steve Bissette, John Totleben and Alan Moore; Aquaman created by Paul Norris and Mort Weisinger; Green Arrow created by George Papp and Weisinger; Katana created by Jim Aparo and Mike W. Barr; Vibe created by Chuck Patton and Conway; Flash created by Infantino, Broome and Robert Kanigher; Wonder Woman created by Willam Moulton Marston and Harry Peter; Supergirl created by Curt Swan and Binder; Superboy created by Siegel and Shuster; Batgirl created by Infantino and Fox; Catwoman created by Finger “and Bob Kane”; Talon created by (I think) Greg Capullo and Scott Snyder; Batwing created by Chris Burnham and Morrison; Nightwing created by Robinson, Finger “and Bob Kane”, plus George Perez and Wolfman; Green Lantern created by (Gil) Kane and Broome; Larfleeze created by Ethan van Sciver and Johns; Jonah Hex created by Tony deZuniga and John Albano; Animal Man created by Infantino and Dave Wood; Swamp Thing created by Bernie Wrightson and Wein; Legion of Super-heroes created by Plastino and Binder; Matter-Eater Lad created by John Forte and Siegel; Metamorpho created by Ramona Fradon and Bob Haney; Conan created by Robert E. Howard; the Atom created by (Gil) Kane and Fox; Adam Strange created by Murphy Anderson and Julius Schwartz; Hawkman created by Dennis Neville and Fox; the Haunted Tank created by Russ Heath and Kanigher; Enemy Ace, Unknown Soldier and Sgt Rock created by Joe Kubert and Kanigher.

Part 3 — Uncle Toby and the Widow Wadman created by Laurence Sterne; Challengers of the Unknown and the Black Racer created by Kirby; Nick Fury, Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, the Vanisher, Unus, Blob, Juggernaut, Stranger, S.H.I.E.L.D. created by Kirby and Lee; Sub-Mariner created by Bill Everett; Ka-Zar “created” by Bob Byrd; Kitty Pryde and Emma Frost created by John Byrne and Claremont; Rogue created by Michael Golden and Claremont; Ant-Man created by Kirby, Lieber and Lee; the Shi’ar created by Dave Cockrum and Claremont; Stryfe “created” by Liefeld and Louise Simonson; Xorn created by Morrison and Frank Quitely.