There have always been books about teens—Jane Eyre, for example, with its eighteen-year-old heroine. Wuthering Heights—it’s just like Twilight, minus the vampires! But as a marketing category, YA (Young Adult) has only existed since the late 1960s. Prior to that, books that were about teens and very popular with teens were not actually marketed to teens. Catcher in The Rye, Chocolates for Breakfast by Pamela Moore, Lord of the Flies, and A Separate Peace were all literary fiction for adults. On the other side, the Nancy Drew books, the Hardy Boyhe s books, and Helen Dore Boylston’s Carol and Sue Barton books were all technically children’s books. Some series, like Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy-Tacy series or the Little House on the Prairie books, followed a character from childhood through the teen years to adulthood and (of course!) marriage. Books that today we would think of as YA, like Beverly Cleary’s Jean and Johnny or The Middle Sister by Lois Duncan, would have been shelved in the children’s section when they were published in 1959.

In 1967 one book changed everything—The Outsiders, a novel about sensitive, misunderstood Oklahoma gang members. Written when its author Susie Hinton was only sixteen, The Outsiders literally has everything a good book could have. This novel was so successful it launched YA as a new marketing category. S.E. Hinton wrote three more killer novels and then—either because she burnt out, was intimidated by her own fame, or simply wanted to do something else like any normal person does—took a long hiatus. Nine years later she came out with a YA novel called Taming The Star Runner which was pretty great but lacked the incandescent power of her earlier novels, and went on to write two picture books, a novel for grown-ups, and a short story collection. The Outsiders has stood the test of time, selling 14 million copies so far, and I imagine it will stay in print until civilization collapses completely. Starting in 1967, there was an explosion of great YA books that you will still find in the library (such as Robert Lipsyte’s The Contender and Paul Zindel’s The Pigman.) Some novels originally conceived for adults, such as Robert Cormier’s incredibly disturbing, violent, awesome, but sometimes misogynist novels, were redirected to a YA audience.

I was lucky enough to grow up during what many call “The Golden Age” of YA, the 1970s and 1980s. (And, to be fair, the late 1960s, before I was born.) The titles alone were amazing. (They’ll Never Make A Movie Starring Me! A Hero Ain’t Nothing But A Sandwich. The Fog Comes On Little Pig Feet. I’m Really Dragged But Nothing Gets Me Down. My Darling, My Hamburger. Dinky Hocker Shoots Smack! Why Did She Have To Die? And I’ll Get There. It Better be Worth the Trip.)The cover art was fabulous. Of course there are great covers today, but no matter how nicely you art design your stock photo, it still looks like a stock photo.

And what was inside these inventively-titled, beautifully-packaged books? Mind blowing stories! “Problem novels” reigned supreme, with the result that sheltered shut-ins like myself got to read about all sorts of lurid topics. Go Ask Alice was the real diary of an anonymous teen drug addict who died of an overdose—except of course it turned out to be fiction. (I did always marvel at how the girl managed to keep such a meticulous diary when she was traveling all over the country stoned out of her mind.) Want to read about a girl becoming an exploited sex worker? Try Steffie Can’t Come Out To Play by Fran Arrick. It was not uncommon for the main character to die at the end, especially if the book was about running away from home. See Dave Run by Jeanette Eyerly (who was writing YA before it was called YA) and Runaway’s Diary by Marilyn Harris were two in particular that broke my young heart.

In 2011 the Wall Street Journal, a periodical that’s always looking out for the best interests of young people, ran a very controversial piece suggesting that contemporary YA was too dark and teens should be offered more upbeat fare. People replied with sensitive, well-reasoned arguments and many teen bloggers offered heartfelt responses about how much YA fiction had helped them when they were struggling with things like suicidal feelings, self-harm, bullying, and eating disorders. But my reaction was, “Where were you in the 1970s, O literary guardians of the wellbeing of the young?”

Although many of these novels were extremely heavy-hitting, they also had more leeway than today’s YA to be “literary” or take their time winding up to the conflict. A Parcel of Patterns by Jill Patton Walsh, a historical novel about the Plague ravaging a 17th Century English town, spends Lord knows how many dozens of pages talking about sheep and rural life before anyone so much as coughs. It makes it so much more disturbing when you finally reach what the book is “about.” Silver by Norma Fox Mazer (rebranded as Sarabeth #1 so it can be part of a series like all the cool books) is very typical of its time in its hyper-realistic, picaresque style. It’s all about a working-class girl who lives in a trailer park with her fun young mom and then transfers to a different school where she makes new friends. About two thirds of the way through the book, the “issue” is introduced. That would never fly today. Today aspiring YA writers are trained to “grab the reader by the throat” in the opening sentences. This is not because experts discovered that young people like to get straight to the point. It’s because in today’s competitive market, agents don’t have time to read more than a page of your novel before deciding that it’s not what they’re looking for.

The line between YA and middle grade (for 8-12 year olds) was blurrier back then too. Silver isn’t really a YA novel by today’s standards, with its twelve-year-old protagonist. Another wonderful classic YA/MG novel with this old-fashioned feel is The Summer of the Swans by Betsy Byars, a contemplative, character-driven novel about a girl whose intellectually disabled brother goes missing. Today only a successful veteran writer like Lois Lowry (The Giver) can still afford to use the slower-paced style from the 1970s that gently wraps you up into a fictional world, and even then typically in middle grade books rather than YA.

But I’m not sorry that the “Golden Age” is over, as much as I loved it. (Pretty much every time anyone starts to get nostalgic for a time gone by, I need to pause and reflect whether me and my friends would have been able to get birth control or kiss the person we liked, just for a couple examples, in those bygone days.) Contemporary YA books have a lot to offer that classic books don’t—like more characters who aren’t white, or LGBTQ characters who make it through the whole book without being raped, beaten up, humiliated, or dying.

Promoting diversity is the battle in YA today. There are little milestones all the time. 2004, the first YA novel featuring a teen who is transgender (Luna by Julie Anne Peters.) 2009, a Latino author (Francisco X. Stork) makes the New York Times list of annual notable children’s books, with his awesome YA novel Marcelo in the Real World, which features a Latino teen on the autism spectrum. 2010, the first YA novel to make the (children’s) bestseller list with a gay main character (Will Grayson, Will Grayson by John Green and David Levithan.) 2014, the first YA book showing two boys kissing on the cover (Two Boys Kissing by David Levithan.)

Sure, it’s fun to read a YA novel about an Olympic athlete that has a coded subtext of same-gender love (Zan Hagen’s Marathon by R.R. Knudson, 1984,) but now you can read a YA novel about an Olympic athlete where the straight-up text is same-gender love (The Next Competitor by K.P. Kincaid.) Why read a YA novel about boarding school life where the idea of being a lesbian makes students vomit and cry with shame (The Last of Eden by Stephanie S. Tolan, 1981), when you can read Openly Straight by Bill Konigsberg or Libba Bray’s Gemma Doyle series for some queer boarding school fun?

YA publishing today is not a shiny Plato’s Republic of respect for diversity. YA novels with LGBTQ main characters or themes represent less than 1% of all YA novels. YA and middle grade books starring people of color make up about 5% of all YA/MG titles. At least on the LGBTQ side, this represents a huge increase over years past. The fact that it’s getting better at all is for the usual reasons, activism and the dedicated hard work of some people in the industry. Every time some damn fool thing happens, readers and professionals rally and push back. Usually without having to put down their phones, because all the dialogue seems to take place on Twitter, Tumblr, etc.

When viewers of the Hunger Games movie began tweeting that it was “awkward” or upsetting or made them lose interest to see the character Rue portrayed by an African-American actor, there was an outpouring of support for diversity in YA novels. (Writer Suzanne Collins clearly described Rue in the novel as having satiny brown skin, but many readers were unable to take that in. What I took away from all this in terms of writing is that it’s a waste of time describing what your characters look like since no one pays any attention to it anyway.) In 2011 when writers Sherwood Smith and Rachel Manija Brown came forward with the story that an agent considering their manuscript had asked them to de-gay some of the characters, the outcome was a campaign called #yesgayya which brought the issue of LGBTQ themes in YA into public discussion amongst the Twitter set.

There’s also a continual outcry against whitewashing, the practice of putting a white face on the cover of a book about a person of color. (What you more frequently see, but it’s harder to say it’s not simply for artistic reasons, is a book about a person of color that has a silhouette or any image that is not a person.) The most publicized example of this was Justine Larbalestier’s Liar in 2009. The original American book cover featured a white teen while in the narrative the teen is African-American. The uproar was so huge that Bloomsbury apologized and changed the cover to a similar image featuring an African-American girl. The probable reason they did such a dumb thing in the first place, against the wishes of the author, was they believed they would sell more copies with a white face on the cover.

The bigger problem is that some people in publishing not only think a cover featuring a person of color won’t sell, they think a book featuring a person of color won’t sell either. And this is also an industry where agents and then editors have to feel mad, overwhelming passion for a book in order to take it on. If there’s anything about a manuscript that makes an editor feel uncomfortable, or makes them feel that they can’t relate to a character, that is a reason to pass.

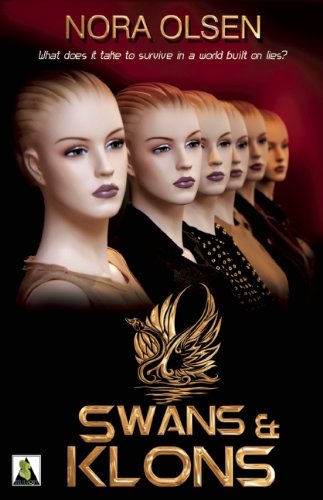

Lucky me, as a writer I no longer have to worry about any of this. I write for a small press that specializes in LGBTQ books, Bold Strokes Books. 30% of all the not-very-many LGBTQ YA titles published each year are published by small presses like this, as well as some publishers who are not part of “the Big Six” but are still quite big from my worm’s eye view, like Disney Hyperion. My only concern would be if I ever wanted to write a YA novel about cisgender heterosexual teens, because then how would I ever get it published? But not all writers are as lucky as I am. Some of us are still toiling away in the foothills of mainstream publishing, hoping that one of those godlike creatures will smile down.

Earlier this month there was a very popular Tumblr campaign called #weneeddiversebooks, in which people posted photos and statements about why everyone benefits from kid lit about people from diverse backgrounds. This happened partially as a response to the announcement of an all-white, all-male panel of “luminaries of children’s literature” at Bookcon (which is a big deal NYC publishing event.) There were many moving and funny statements. My favorites: 1) Two guys holding signs that said, “I’m not him, but I’d like to get to know him better.” 2) ‘#WeNeedDiversesBooks because “my sister has Down Syndrome” followed by “my sister has a black belt” shouldn’t catch everyone so off guard. Books show casing people with disabilities excelling or kicking butt would educate the general public, and show others with disabilities that being the star, saving the day, or being the heroine is something they can also strive towards.’ 3) “#weneeddiversebooks because if I’d ever seen myself in fiction, I might’ve understood myself better and not have been driven to suicidal-depression and self-harm as a teenager.” 4) A tall boy with a basketball holding a sign saying “Because I like pink too!” 5) “#WeNeedDiverseBooks because i’m black, queer, fat, and a bunch of other marginalized and oppressed identities. And I want to be the hero and ride a fucking dragon in books too.”

The natural corollary of campaigns like this is encouraging people to support diverse YA by buying it. If the industry think diverse books don’t sell well, prove them wrong. If you say you want to read books about a more diverse swathe of characters, prove it. If you don’t have money to be buying all these new books, put them on hold at the library—trust me, those librarians are keeping track of what books are popular.

It’s still true that most readers of YA (Young Adult) books are teens. But just barely. Almost half of YA readers are over eighteen, with the 30-44 year olds accounting for 28% of sales. If you picked up The Fault in Our Stars or the Harry Potter books, you were reading YA too. There’s a new genre developing called “New Adult” that aims to appeal to this older segment of the readership by combining the magic of YA with more adult things, like explicit sex. New Adult books mostly feature college-aged protagonists because otherwise, ick!

What is the enduring charm of YA? I think it’s simple. YA delivers more reliably than literary fiction, which can be so awful. YA needs a strong storyline to keep teens’ attention otherwise they will put the book down. And it must have heart and authenticity, because young people are exquisitely calibrated bullshit detectors. If you haven’t read any YA since you were a youngster, think carefully before you try it. You might be hooked for life.