I’m shocked to report that spending July 4th in Bath means no Fourth of July fireworks. For some reason England doesn’t seem to celebrate the holiday. So this year I’ll have to settle for all-American superhero analysis instead:

The Declaration of Independence is, according to Noam Chomsky, the first American superhero text. A student asked the world-renown linguist and political commentator about the onslaught of zombies in American theaters and TVs, and he explained that in American pop lit, we’re always “about to face destruction from some terrible, awesome enemy, and at the last moment we’re saved by a superhero.”

John Lawrence and Robert Jewett call it The Myth of the American Superhero: “Spiderman and Superman contend against criminals and spies just as the Lone Ranger puts down threats by greedy frontier gangs. Thus paradise is depicted as repeatedly under siege, its citizens pressed down by alien forces too powerful for democratic institutions to quell.”

“So you go back to the early years,” Chomsky explains, “the terrible enemy was the Indians,” those flesh-devouring monsters Thomas Jefferson called “the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.”

They include those folks who mercilessly rescued the first boatload of pilgrims from starvation. Also please ignore the fact that Jefferson’s fellow founders signed a treaty with some zombie hordes that would have made the Delaware tribe the fourteenth state of the new Union. Like the vast majority of U.S. treaties, things didn’t work out as stated.

“It turns out,” says Noam, “this enemy, this horrible enemy that’s going to destroy us, is someone we’re oppressing.” He explains the reversal as “a recognition — at some level of the psyche — that if you’ve got your boot on somebody’s neck, there’s something wrong, and that the people you’re oppressing may rise up and defend themselves, and then you’re in trouble.”

So Jefferson put the focus on the supervillainous King George instead: “The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.” The list of offenses includes plundering, ravaging, and completing “the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.”And for a final outrage, George also “excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers,” those aforementioned, George-like savages.

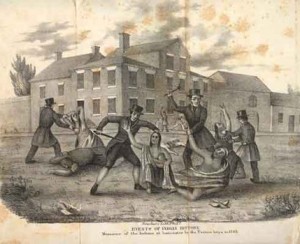

Since its founding document, America has defined itself as a champion of the oppressed—even when it’s been busy oppressing the oppressed. I grew up in Pittsburgh, home of the first recorded act of germ warfare. When two chiefs visited Fort Pitt in 1763 to offer its besieged inhabitants safe retreat from Indian territory, the British commander declined but presented them with a gift of smallpox-infected blankets, hoping they would “have the desired effect.” Next Rev. John “Fighting Parson” Elder was rousing hordes of merciless vigilantes to ride to the rescue and attack Indians living among settlers. “These poor defenseless creatures,” wrote Ben Franklin, “were immediately fired upon, stabbed, and hatcheted to Death!” When the Pennsylvania governor posted rewards, no one turned in the murderers because, Rev. Elder explained, “the men in private life are virtuous and respectable; not cruel, but mild and merciful.”

&nsp;

America is schizophrenic. We were founded on alter egos. And yet Francis Parkman, while chronicling Pontiac’s so-called Conspiracy, declares the Indian to be full of “contradiction”: “A wild love of liberty, an utter intolerance of control, lie at the basis of his character, and fire his whole existence. Yet, in spite of this haughty independence, he is a devout hero-worshipper; and high achievement in war or policy touches a chord to which his nature never fails to respond. He looks up with admiring reverence to the sages and heroes of his tribe.”

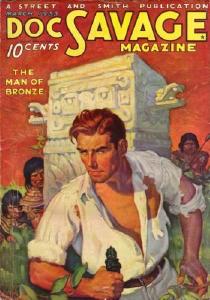

That same liberty-loving hero-worship infuses the schizophrenic character of our American supermen. Of course we adore alter egos. Robert Bird’s proto-Batman, Nick of the Woods, isn’t the only frontiersman suffering from multiple personalities: the Quaker-by-day doesn’t seem to know he’s also an Indian-killing demon-by-night. I prefer Doc Savage and the contorted narrative tricks his writer Lester Dent has to play to avoid the obvious. The character is named after a real-life Colonel Savage, “a hero of the Spanish-American War,” in which the U.S. seized Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines from Spain. In his 1932 debut, Doc Savage travels through Central America to find “the Valley of the Vanished” where no “outside races have intermarried” with “the high class of Mayan” believed extinct since Spanish colonization. Though a Mayan princess, apparently attracted by Savage’s racially ambiguous bronze skin, would love to intermarry, he returns to New York with a gift of gold from “the treasure trove of ancient Maya” to finance his do-gooding missions.

It’s a peculiarly American take on colonization, where the colonized are not only willingly plundered but must remain hidden in a static preserve unrelated to any of those actual Indians openly impoverished within the borders of the contemporary U.S. John Carlos Rowe calls it our “contradictory self-conceptions”: “Americans’ interpretations of themselves as people are shaped by a powerful imperial desire and a profound anti-colonial temper.”

That duality also accounts for America’s “paranoid streak.” “The United States is an unusually frightened country,” says Chomsky. “And in such circumstances, people concoct either for escape or maybe out of relief, fears that terrible things happen.” Chomsky’s list of later zombified fears include revolting slaves and “Hispanic narco-traffickers.” If his classroom Skype interview hadn’t lurched to the next question, I think he would have added the hordes of Muslims currently clawing at the gate of America wilderness fort.

Osama bin Laden’s “Declaration of War against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places” bears an uncomfortable resemblance to “The Declaration of Independence.” Bin Laden wrote two fatwas before 9/11, both roughly the length of our founding text. He lists “crimes and sins committed by the Americans,” calling them “facts that are known to everyone.” Jefferson lets his “Facts be submitted to a candid world,” detailing England’s “abuses and usurpations.” Like King George’s “establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States,” America is “plundering its riches, dictating to its rulers, humiliating its people, terrorizing its neighbors.” Both declare the “duty” and “honor” of the oppressed to fight for “justice,” evoking Allah and “Nature’s God” in support: “Our Lord, rescue us . . . and raise for us from thee one who will help!”