Thanks, Mike! What is Donald Phelps saying about Seuss/Sendak? To give me an idea, Mike lines up relevant quotes out of the Phelps piece (scroll down). The picture grows more and more clear. Yet I have a long way to go.

Monthly Archives: December 2008

Bill and Jon Come Through

the bounds of what’s imaginable, with a sense that certain imaginings, depending on where in the mind they’re from, come with different rules of use.

Thanks. I posted here about my need for a plain-English translation of Donald Phelps’s Seuss/Sendaka article. Bill Randall and Jon Hastings posted in Comments, and now I have two plain-english summaries to be getting on with. They posted damn solidly too. You can check out the full versions here.

“Form entails a sense of the imagination’s geography and its component laws.” Seuss breaks those laws; Sendak doesn’t.??For Phelps, form is art; specifically, it’s the form embodied in any individual work of art. He calls it “judicious awareness of locality.”…The Marx Brothers’ late works violated the vaudeville form that defined them; Seuss likewise failed for abandoning the integrity of his stories in favor of commodity. Phelps faults him for ditching the terms of the story for an awareness of the audience as consumers.…The quaint/cozy opening sets up the tone of reminisce– this one’s more prosaic than usual– and contrasts modern consumer tastes with gentler, older tastes. (Seuss is more revered by modern taste than Sendak …)

… edginess” means that the creator is working at or beyond the boundaries of conventions: it’s a challenge to the audience’s expectations. Challenge is aggressive.

Edginess is competetive in that, in any dynamic, living genre, the boundaries of the conventions are always moving.

My Phelps Bleg Again

I’ve been asking for help understanding Donald Phelps’s essay on Maurice Sendak and Dr. Seuss. Basically, I’d like to read a plain-English version of what he’s saying. A one-paragraph summary would be fine, two paragraphs if that’s what it takes, or whatever you think is right. Or a full-text rendition, of course. Or nothing, since people have things to do besides helping me out.

Anyway, in the last post’s comments Layla tackles the question of aggressive/competitive strangeness. She suggests that Mr. Phelps has in mind “strangeness that is ‘edgy,’ which is more aggressive and in your face and which is viewed (at least today) as positive.” So, by Layla’s reading, we’re talking about edginess vs. quaintness, with quaintness now being outmoded and in low repute, and with the essential difference between the two being that “edginess” is aggressive toward the audience.

Layla, thanks for the hand, I hope I got what you’re saying.

For her, or anyone who feels like it, a few follow-ups:

1) how is edginess aggressive toward the audience?

2) how is edginess “competitive”? is the idea that edgy output is always trying to top other edgy product, trying to seem stranger?

3) if that is the idea, does it seem plausible to people that quaint product isn’t trying to out-strange other quaint product?

4) if that isn’t the idea, what is?

Fact

DeForest Kelley spent World War II stationed at the air force base in Roswell, New Mexico.

I like big books and I cannot lie

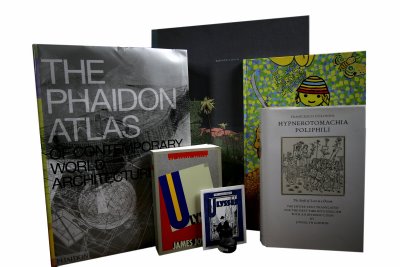

Here, with the other largest books I own, is it. Taken with a 16-35mm lens on the wider end of the zoom. KE7 is in the back; it’s bigger than it looks, due to the lens distortion.

For reference, that’s Chippendale’s mammoth Ninja on the right. Contemporary World Architecture on the left comes with a plastic briefcase so you can actually carry the thing. The only book I know bigger than KE7 is GOAT; it weighs 75 pounds, and the copy I saw covered an entire table. So KE7‘s smaller & cheaper; GOAT‘s like 4 grand.

I’ve paged through KE7 twice, but I don’t know how to read it. Maybe on a podium standing up. In the Parthenon. The best comics, I couldn’t get close enough to read at the words.

For the others, several disappoint me– Jaime Hernandez’s, for instance– for failing to address the scale. Others, like the Johnny Ryan page, disappoint for being boring cover versions of himself. (And including them over, say, Vanessa Davis, Renee French, Lauren Weinstein, and Geneviève Castrée’s a shame. And a chance to note that only four women artists are in the book, for whatever reason; I would have liked to see a Lynda Barry collage rather than coprophiliac doodles.) The exception that proves the rule for these is John Hankiewicz’s entry, with the same panel drawn over and over, wonderfully, unrelentingly claustrophobic.

The best works are quite stunning. And a fulfillment of the promise of KE4. They come from cartoonists active as painters and printmakers– like Leif Goldberg, whose comics I dislike but whose prints I collect. And Nilsen, Santoro, Furie, Boyle. Carol Tyler has a beautifully painted page; Kevin H. seems to sum up his career in just a few giant panels. Ben Katchor plays with scale first, then with newspaper format; Tom Gauld shows off why his art’s simplicity is deceptive. CF turns in a double-splash that looks as good as any of his silkscreen prints.

You could buy 50-60 frames, cut the spine, and open a gallery.

The two artists who best exemplify KE7 are Dan Zettwoch and Xavier Robel (half of Elvis Studio). Zettowch turns in an epic from the tailgate to the gridiron; Robel’s got some insane constructivism going on. One’s traditional, one experimental; both brilliantly pitch scale and color against the unique opportunity of these huge, huge pages.

Select British Eloquence

Tom’s been talking about his inability to understand Donald Phelps’ prose. I mentioned my dislike of Phelps’ writing earlier. I think, though, that it’s only fair to point out that opaque prose is not necessarily something that I’m against in every instance. As proof, I thought I’d print one of my prose poems from some years back, when I wrote such things.

This is based on Select British Eloquence, a 19th century rhetoric textbook by one Chauncey Allen Goodrich. I wrote it by taking some of his sentences and switching words and phrases of my own in and out. Eagle-eyed readers may be able to spot the origin of this blog’s title, though I doubt most people will get that far. In any case, here ’tis. Eat your heart out, Donald Phelps.

**********

Variation on Select British Eloquence by Chauncey Allen Goodrich (1852), with an introduction by A. Craig Baird (1963)

“The oratory of Charles Darwin,” noted Mr. Karl Marx, “was uniquely suited to the theme of the origin of specie; not only did it open, like a luminous shower of golden boxes to reveal perfumed lumpen proles in whose sullen mental tergiversations the wild wealth of pensions struggled till sufficiently fit to be invested with the gay habits of usorious semites, but it also closed within its tinkling xanthic cataracts those prostrate securities which must be eliminated through probity and private rectitude if teleological apocalypse is to come. When, mounted upon his bloody posterity, he rode out over the Western force of historical materialism with jingling padlocks on his virile imperatives and Mao Tse Tung by his side, even Lord Vader — no friend to Natty Bumppo’s raw, Rousseauian marketing Jüngness — was moved to the following eulogium: ‘His defense of Rockefeller and Gates from the overly fastidious savagery of weak-minded poor rates defiled evil and degraded apathy; it showed every discerning malefactor that only mercantilism’s unremitting actuality could be justly considered truly brutal. One listened to it with a mixture of voluptuous impiety and copious vacancy, until suddenly, before one could say “never tell a lie,” one found oneself up to one’s wooden teeth in happy Negroes.'” Clearly the bloom-on-the-rose appeal of self-assertion by scientific statesmen had reblossomed — leavened, perhaps, with the fertilizing yeast of honor — and anthropological authority was once again perceived as the thorn with which rich and powerful pricks might procure necessitous, supple virtues from innumerable vice-ridden climes. Armed only with a tape measure and sprightly sallies of obsequious condescension, compulsive phrenologists began to classify with impunity every man-servant by the magnitude of his erect countenance and, subsequently, to organize for each a tour of the corrupt capitals of Europe during which, they sincerely hoped, prodigious indigenous flab would stimulate the exquisitely tentative penetralia of unpolluted Frenchwomen to write novels of social protest. Such strenuous employment — requiring the analysis and digestion of vast, shapeless ethnics — is the angelic equipage that, if supported by parental liberality, will carry a reforming aesthete out of the temperate gated estates of his aery navel, through open champaigns bubbling with the thermal rhythmus of racy literature, and into charity bazaars where, at one brightly draped cathexis, graceful maidens with pitchers on their heads and republican enthusiasm in their dark machines alchemically concentrate the wandering glances of colonial ravishers while, at another, orphans resting sweetly in specimen jars soften the austere and turgid wearisomeness of £10,000,000 — I mean, they are chained to siphoning apparatuses which distill their biographies into rational policies or coffee-house apotheoses. Similarly, the essence of the simple man of the earth may be woven into dusky breeches for his betters, thereby ensuring that the albino bottoms of incontinent worthies are never the butt of shameful ramifications and that, when an inevitable besmirchment regretfully occurs, it does so but obscurely. These, then, were the valuable carbuncles wrested from wretched refuse’s ruined flesh by the abstruser inquiries of vivisection! Detached body parts of extraordinary force and beauty are undoubtedly useful in peddling spirits, nostrums, and undergarments; if dwelt upon exclusively, however, they are sure to vitiate the taste, and thus place between the man of leisure and the full enjoyment of degenerate strumpets a concave speculum of morose function which, instead of refracting light, bends ardor, focusing concupiscence solely upon distaff forms of unimpeachable pulchritude, rather than allowing coruscations of amatory interest to scatter and twinkle upon the variegated subtleties of delight suggested by, for instance, overly adipose hindquarters, feminist viragos, or a dirty-faced urchin. Of course, if avarice had been unnaturally constrained by the deadening prophylactic sheath of taste and discrimination, or if the acquisitive talent had not been given boundless scope in which to discharge its manly romanticism, the parturient labor of Adam Smith could never have brought forth such an ample imaum as Henry Kissinger. As it was, his pickled intellect was spread wide to commercial intercourse from the remotest part of the globe, and the stream of surplus revenue — once it had penetrated his ductile syllogism — found in him a fecund New Haven where the healthy seed of sinecure might grow into the mighty oak of a Yale undergraduate, and the acorn of substantial liberal humanist ancestry sprout into the squirrel of shameless oppression. He knew that the most potent engine of chaste Irish pathos for the professional class was that vocem exiguam, the shrill and stumbling brogue of the Amerindian, which, in its extemporaneous Attic eloquence, so memorably inspired the Marquis de Lafayette to strip off all his garments, don a Malcolm X cap, and quip “Ich ben ein Berliner.” It is hardly necessary to add that this boyish hilarity soon led organically to a didactic enumeration of Russian armament. In a speech of five hours long delivered at the society for Speculative Microcosm Management, Benjamin Franklin — who was, at that time, although young, already an authentic philosopher-ninja, in full possession of his gigantic Eternal Wisdom powers, able to mutate sombre abolitionism’s sterile upright moralism into practical compromise’s cheerfully crippled dissipation by launching from his noble-browed bosom burning bolts of electric gout — explained that the irresistible seductions of Turkish perversions would indeed, if not enervated, relax the solids of the national body, resulting in despotic Oriental dropsy, but that there was no real cause for alarm, as he was prepared to develop an entirely new science of Unitarian ferocity: a science which could forge the withering interrogatories associated with universal philanthropy into an assemblage of levers and pulleys by the secret use of which the common tongue could be extracted and placed, gently but firmly, on the elegantly mangled teat of self-reliance, inducing the abandoned imperial sow to carry her healthy system to an early grave in a foreign constitution. The aforementioned truths, being of imperishable value, could not help but make the structure of his mind a household institution, like the microwave ovens which wait in the forest of Africa to fall, without a moment’s warning, upon the Groom of the Bedchamber, wrap him in a palliative maze of metaphorical confusion, and throw him down, by analogy, upon Mr. Isaac Newton, prompting that impetuous entrepreneurial treasure to invent John Wayne and then, against all the tenets of gravity, to drop him upwards — past pine tops waving with ancient relevancies — past winds breathing with the deliquesced corpses of indigent men of genius — past splendid puppets dreaming of sociology flowing through the polished interior ministries of space — in short, past all gross sublimity and encumbrance, and into the silent sidereal well where the drowned Gospels’ maxims are whelmed by the Britannica’s wider views, there to rest, massively indolent, until the prophesied time when his merciless generalizations and robust know-how will be needed to strategically defend us from the short-sighted imbecilities of grog-quaffing journeymen. Amidst the ferocious mobs of humble seekers methodically snubbing the supposedly befuddled constables whose salaries they subsidize, who but he understood that pedantry is not a means, but rather a blank and glorious end, fulfilling in every particular the hopes expressed by the first mute and hairy Australopithecine when, drawing about him his primitive flint nanomachines, he inscribed the shadow of a wooly shibboleth on the wall of his cave under the assiduous misconception that, as George Will states, “striking the chtonic umbra would slay the Platonic pundit lurking beyond the circle of the Internet’s wet, red glow; he could then dismember me, fashion an imitation firmament from my foreskin and a counterfeit fundament from my diaphragm, and reside thereafter in a mammoth bag of nugatory echoes, ever sipping sagacity from my engorged logos (an act of false deiphage which, if prolonged indefinitely, promised to make man a vestigial appendage of his own evolving jaw)”? Who other than he possessed a drain in his forehead down which recipients of Poor Relief — flushed from the strain of having their ethically defective super-egos replaced with magnetized subcutaneous case-workers — swirled with such majestic abjection that hooligans expelled from Public Skulls, long thoughtlessly de facto, were recalled, like René Descartes, to the cortex, and embalmed in beautiful Panopticons? His later life was saddened when he realized that the Industrial Revolution, or, more specifically, the invention of the pneumatic Bastille, had elevated sissified diction to a position of mastery formerly reserved for the epistles of our Founding Fathers, and that his decision to accept undisciplined kisses from the libertine lips of militant militiamen had transformed him into a prince of purity at the precise historical instant that amphibious miscegenists — who, we now know, achieved photogenic, desultory diversity by moistening their thin skins with the secretions of leprous domestics — seized control of the United Nations, and began to suppress with tolerant “Brrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrraaaaaaaaaaaaaaaacks” not only Islamic dissent, but also his own personal, patented brand of Milton’s Peppery Anti-Popery, long used, in accordance with the hopes of his friends and the demands of his wife, to season a potpourri of after-school pogroms cooked up for young, troubled Princesses in danger of becoming Whores of Babylon. Yet, even in adversity, he never lost his Elgin Marbles, which continued, until his death, to blare from his famous and scrupulous blunderbuss whenever perfidious philistine microcephalouses, forgetful alike of verbal chastisement and brutal bludgeoning, dared to blaspheme the radar screen of Zeus by creeping from their proper station in the woodpile. To inflict peremptory punishments, without in any way adverting to the Euclidean theorems of bilious jurisprudence constructed by compass, protractor, and inverse geometric peristalsis from Everyman’s inalienable intestine, at the least calls for an advertorial-cum-apologia, if it does not, indeed, merit severe animadversion and obloquy. We must remember, however, that, at that period, the heroic champions of natural law — Captain Leviathan, Prerogative Lad, the Iron Advocate and his pal Magna Cartridge, Miss Manners, Apriorion, King James Bivalve (a.k.a. the Submarine Sahib), and even the Hooded Utilitarian — were animated by an antinomian afflatus; it is fair to say that the wits of the wiliest warden then could not have secured what now the merest traffic cop apprehends, viz. — that, at the Hall of Justice, super-powered stenographers have, in the interest of putting the “auteur” back into “authoritarian,” grown countless Shakespeare-clones from the Bard’s vile, sycophantic jelly — that these clones, when the monarch’s pet monkey defecates upon their silly, genuflecting goatees, moan forth, in stochastic rapture, “O! O! O!” “Sa, sa, sa, sa!” “Et tu,” &c. —and that, before the Last Judgement, the transcription of these susurrant vocables is certain to spell out, in the supine scripture of the avant-garde, a perfect municipal code.

The Phelps Essay About Dr. Seuss and Maurice Sendak

Noah criticized it here. Over at The Comics Journal I posted this:

I read the Don Phelps essay and had a lot of trouble with the writing. Sentence by sentence, I just couldn’t understand what he was saying. Can anybody here try a plain-English summary?

The governing, underlying charm of “quaintness,” I suspect, lies in the stable universe the word suggests a manifest willingness to abide, albeit in some obscure nook or oddly shaped frame — to which another widely disdained word, “cozy,” may be applicable. “Quaintness” suggests a residence that is stable, even static; it suggests, too, a heritage of peacefully disposed experience.

“Quaintness” is charming because it suggests a stable universe — even though that universe may be odd or obscure. “Quaintness” is also attractive because it refers to a peaceful heritage or tradition.

How often does one encounter the word today? Much less, with (even gently) approving overtones. “Outdated,” “folksy,” slightly moldy? Disdain for, impatience with, a sort of strangeness that is noncompetitive and nonaggressive. Even in the field of children’s art and literature. Take two leading names in this country: Dr. Seuss (aka Theodore Giesel) and Maurice Sendak.

Noah’s translation of second paragraph:

Today the word “quaintness” is usually taken as a negative. This is because people disdain strangeness which is noncompetitive or nonagressive. Quaintness is even disparaged in the work of Dr. Seuss and Maurice Sendak. [That last bit is my best guess; the prose actually seems to be saying that Seuss and Sendak dislike the use of the word “quaintness” — but I can’t believe that’s what he means. I think instead he’s trying to say that quaintness is denigrated, and that as a result it makes people dislike even the work of Seuss and Sendak.]

Does anyone have any more? Note: an explanation of “strangeness that is noncompetitive and nonaggressive” would go a long way toward helping me get this.