“How much more basic can you get? I made up a superhero and named him ‘Power.’”—David Mazzucchelli describing the cartoons he drew as a child, from his Comics Journal #194 interview (1997).

How should we evaluate David Mazzucchelli’s career?

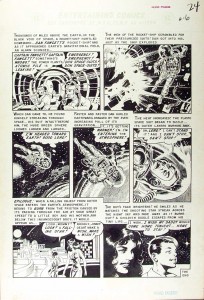

His work tends to fall neatly into three chronological periods. The first is his superhero period (1984-89), when Mazzucchelli was an artist for Marvel and DC, making splashes collaborating with Frank Miller on the Daredevil: Born Again (Daredevil #227-233, 1985-6) and Batman: Year One (Batman #404-407, 1986-7) story arcs. There were also a few single issues that Mazzucchelli drew during this period, such as a story written by Ann Nocenti (and starring Angel of the X-Men) in Marvel Fanfare #40 (1988).

The second period includes Mazzucchelli’s shift into art-comix with the three self-published issues of Rubber Blanket (1991-93), along with short pieces for anthologies like Snake Eyes, Drawn and Quarterly and Zero Zero, and his adaptation of Paul Auster’s novel City of Glass with Paul Karasik (1994). This second period ends around 2000, as his stories stopped appearing in anthology comics. Since then, Mazzucchelli has focused on his job as a teacher at the School of Visual Arts while laboring steadily on Asterios Polyp, which represents to me an achievement auspicious enough to herald a new period in his career, devoted to the self-contained, available-in-mainstream bookstores, graphic novel mode of publishing. He’s come a long way from floppies to hardcovers, from Marvel to Pantheon.

A danger of dissecting an artist’s career into discrete periods, though, is that we risk losing sight of the themes and tropes which remain consistent across individual works. This risk is especially great with Mazzucchelli because Daredevil is so different, at least on the surface, from Asterios Polyp. Polyp, however, includes at least one specific reference to Mazzucchelli’s previous comics. In “Chapter Seven,” the unlabeled chapter that begins with a portrait of a mosquito (and why doesn’t this book have page numbers?), Asterios and Stiff visit a diner and talk with a man named Steven “Spotty” Drizzle. As Derik points out, we’ve seen Mr. Drizzle before; he’s the main character in “Near Miss,” a tale in Rubber Blanket #1 (1991) that begins with Steven abandoning his family and bourgeois lifestyle because of his panic that a meteorite could crash into the earth and kill off the human race. In his cameo in Polyp, Steven remains terrified of asteroids, and Asterios responds with a not-so-reassuring scientific mini-lecture.

Whipped into a frenzy by Asterios, Steven runs out of the diner and the book, never to return. There’s much to be said about the importance of asteroids in Polyp (again, read Derik), but I’m intrigued by Mazzucchelli’s re-use of a previous character. Is Mazzucchelli establishing continuity (a Mazzucchelli-verse) between his Rubber Blanket stories and Polyp? Is it possible (and useful) to chart similarities between Mazzucchelli’s Daredevil and Batman runs and his later alt-comic books? In an attempt to answer these questions, I re-read as much of Mazzucchelli’s comics as I could (I’ve never found an affordable copy of Rubber Blanket #2 [1992], though I did dig up X-Factor #16 [1987]) and found at least a couple of elements tying Mazzucchelli’s career together.

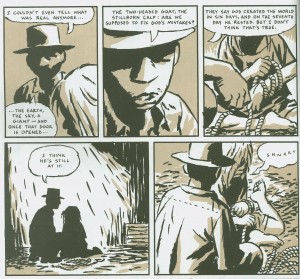

Mazzucchelli is interested in graphic representations of greater-than-human power. The longest story in Rubber Blanket #3 (1993) is “Big Man,” designed by Mazzucchelli as a tribute to Jack Kirby. “Big Man” begins as the eponymous character—impossibly tall and broad, like Kirby’s Hulk—washes up on a beach, his arms and legs tied to a wooden raft. Big Man is discovered in this state by the citizens of a small farming community, who drive him to a barn, feed him, and give him chores to do like planting trees, building fences and digging ditches. Big Man shows his true Hulk-like strength, however, when he single-handedly lifts a tractor off a trapped farmer. There’s a terrific sequence on page 39 showing Big Man pitching the tractor to one side, and then flashing a goofy smile (drawn as a close-up) at the awestruck farmers at the scene of the emergency. Then comes a splash page of Big Man from the farmers’ point of view.

Mazzucchelli’s expressionism is at full throttle here: representational forms are abstracted into thick brush strokes of ink—look at those clouds slashing across the sky—and Big Man has the spot-black weight and solidity of an allegorical figure from a Lynd Ward woodcut novel. (Mazzucchelli isn’t aping Kirby’s style, but he’s emulating Kirby by emphasizing a character’s power, even when s/he is standing still.) The low angle of the splash’s composition underlines Big Man’s looming stature, displaying him as massive enough to block out the sun with his left shoulder. For the rest of the story, a farmer named Peter struggles to understand Big Man’s superhuman power, and concludes that such power could only be conferred by a God committed to the ongoing creation of new and wondrous beings.

Polyp opens with its own version of supernatural agency, a lightning bolt that strikes Asterios’ apartment building. On the book’s third page, a splash captures the lightning blasting down from the sky, from a position close to the clouds. The low-angle portrait of Big Man is through human eyes peering up at a giant, but Polyp’s high-angle lightning splash seems almost from the point of view of God looking down at the rain and the city, and taking aim.

Four pages later, the power of the lightning bolt is revealed in another splash, as Asterios’ bedroom is bathed in white light and his television short-circuits. Asterios was watching an old videotape of a romantic dinner between himself and his ex-wife Hana, but the bolt erases those memories, and lights Asterios’ apartment building on fire, leaving him homeless and rootless. The forces of nature reassert themselves at Polyp’s conclusion, as Asterios and Hana reunite right before a meteorite flies into the atmosphere, on a path to kill them both. This meteor is Mazzucchelli’s most powerful symbol of greater-than-human power so far: its path of destruction is revealed in an epic double-page spread that abruptly shifts the reader from the micro-scale of Hana and Asterios’ tentative reconciliation to the macro-scale of an impending Velikovskian disaster, a shift that returns us to Kirby-land.

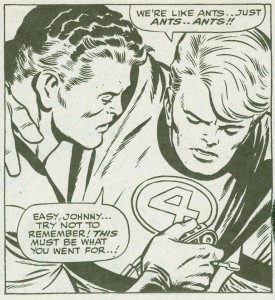

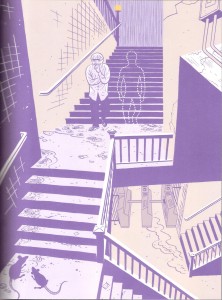

To be sure, Mazzucchelli’s stories are littered with “ants” who are victims of natural disasters, random crime, or just bad luck. Capricious violence is a convention of the noir genre, so it’s no surprise that the Miller/Mazzucchelli noir-flavored Daredevils and Batmans have high body counts, but this is sometimes true of Mazzucchelli’s alt-comix as well. In “Rates of Exchange” (Drawn and Quarterly volume 2, number 2 [1994]), a listless expatriate named Anthony lands in a cheap Parisian hotel, where he makes friends with some of the hotel’s guests. One of the more enigmatic guests is a middle-aged woman who passes Anthony in the hallway, always with a cheery smile and a “Bonjour”—until she is strangled to death by her husband. Anthony, stunned by the news, still imagines her presence in the hallway.

The broken lines that signify the murdered woman remind us of the ultimate senseless death in all of Mazzucchelli’s oeuvre, that of Ignazio, Asterios’ twin brother, who was found dead in the womb during their shared C-section. Ignazio is Mazzucchelli’s cri de coeur against chaos, against unfairness, against all those cosmic forces that operate beyond our comprehension. In the real world, children die for no good reason, but in Polyp, they can at least narrate the stories of their living siblings, and accompany them, like ghosts or shadows, though the vicissitudes of their lives.

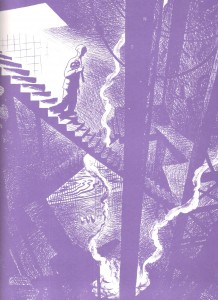

Another element common to the various periods of Mazzucchelli’s career is his use of plotlines where a central protagonist is brought low, and remakes himself, better than before, after hitting bottom. In Daredevil: Born Again, the Kingpin finds out Daredevil’s secret identity as lawyer Matt Murdock, and secretly dismantles Matt’s domestic life. Thanks to the Kingpin’s machinations, Matt loses his home in a bank foreclosure, and has all his assets frozen by an IRS audit.

Soon after, he is unjustly disbarred for perjury. Daredevil becomes “a lost man, thrashing,” who finally suffers a mental breakdown after the Kingpin recklessly bombs his foreclosed brownstone. (Issue #228 opens with Matt sleeping in a tight fetal position on the bed of a scummy hotel room; #229 opens with him sleeping in a still-tighter fetal position in a dark alleyway, surrounded by winos.) Finally, he staggers back to his childhood neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen, where he is nursed back to health by a nun (who, improbably and melodramatically, turns out to be his long-lost mother!) and builds a new life. He takes a job as a line cook at a neighborhood mission, he forgives and falls in love again with a traitorous junkie ex-girlfriend, and he resumes his identity as Daredevil to stop a Kingpin-hired super-soldier named Nuke from reducing Hell’s Kitchen to rubble. (Yes, Born Again is an uneasy mix of noiresque verisimilitude and superhero antics.) The story essentially reboots Daredevil as a more humble, more authentic champion of the ‘hood.

There are numerous similarities between Matt and Asterios, and between Born Again and Polyp, and maybe the best way to cover these similarities is with a list.

- Both stories open with their main characters in states of disarray and disillusion visually represented by bad news in the mail. Matt gets the foreclosure and audit notices, and on page 6 of Polyp, even before we see Asterios, Mazzucchelli prepares us for trouble by showing us a pile of “past due” bills on his desk.

- Both Matt and Asterios are “blown out” of their upscale living quarters, and both tumble into homelessness and purposelessness after these catastrophes.

- As Matt and Asterios bottom out, they meet kind strangers who give them support they need. Matt’s savior is Sister Maggie, the nun—though Miller indicates that Maggie knows that she’s Matt’s mother, and that’s one of her motivations for helping him. (She’s a stranger to Matt only for a brief time, until he practices one of his Daredevil tricks—listening to a person’s heartbeat—to discover who she is.) Asterios’ generous strangers are the surrogate family (Stiff, Ursula, Jackson, Gerry, Mañana) he cobbles together in the small town of Apogee.

- Both Matt and Asterios shed their prestigious careers; when they restructure their lives, they opt for menial jobs instead. Matt goes from high-flying lawyer to mission chef, while Asterios abandons his position as a professor of architecture. Near the beginning of Polyp, we see Asterios interact with several students—mostly through snotty comments like “There are just two things you need to fix here: the interior and the exterior”—but he leaves academia behind when he rides the bus to an arbitrary destination, meets Stiff, and trains himself to be a car mechanic.

- Both reunite with lost loves: Matt with Karen Page, Asterios with Hana.

- Both Born Again and Polyp include religious symbolism. Both Matt and Asterios are Job surrogates (though both are more flawed than Job when their misfortunes begin to occur). Catholicism, in the forms of Sister Maggie, crosses, and the ironic juxtaposition of heroism and a devil figure, permeates Born Again, while mythology is shot through every inch of Polyp, perhaps most notably in Mazzucchelli’s wordless retelling of the Orpheus/Eurydice story with Asterios, Hana, and Willy Ilium (love that name!) as Pluto.

- Loss of vision affects Matt and Asterios. Blindness is, of course, an essential part of Daredevil’s origin. His abilities as a crime fighter came from a radioactive isotope that destroyed his eyes but ramped up his other senses. Miller and Mazzucchelli remind us of Daredevil’s blindness by retelling his origin in issue #229 in a unique way: they use pages dominated by rows of vertical black panels and free floating word balloons to render us as blind, and as dependent on hearing, as Matt.

- Poor Asterios is seemingly fated to suffer eye trauma. On page twenty of Polyp, Mazzucchelli writes that Asterios’ immigrant father had a name that “an exasperated Ellis Island official” cut in half to make “Polyp.” His initial longer name is “Polyphemus,” the monstrous son of the Greek god of the sea, Poseidon, and also the Cyclops who is blinded by Odysseus’ men in the Odyssey. True to his namesake, and akin to Daredevil’s own “injury motif,” Asterios loses an eye before the conclusion of his own book.

I’m not sure what to think about the similarities I’ve charted among Mazzucchelli’s diverse books; I can’t figure out if he consciously based elements of Polyp on Born Again or not. (The story points I list above aren’t exactly original with Mazzucchelli.) I can talk about the effect these connections have on me as a reader, though, and on reflection I am disappointed to see “power” remain a major concern for Mazzucchelli, because after reading superhero comics for 40 years, I’m tired of impossibly strong golems and crackling lightning bolts. I care much more about Hana and Asterios than I do about some Armageddon-inducing meteorite, so for me the ending of Polyp seems to privilege “power” and “fate”—two key concepts of the superhero genre—over Hana and Asterios’ relationship.

In the last four pages of Polyp, Stiff, Ursula and their son Jackson sit in the treehouse Asterios helped to build, and they see a “shooting star” streak across the sky, almost certainly the meteor poised to decimate Hana’s house. Ursula encourages Jackson to “make a wish” on the star. This scene is a sideways reference to an earlier comics story, one not drawn or written by Mazzucchelli. In Weird Fantasy #13 (1952), Al Feldstein and Bill Gaines wrote and Wally Wood drew a science fiction story called “Home to Stay,” about the sorrow a boy feels when his astronaut father is always away on space missions. (The tale shamelessly plagiarizes two Ray Bradbury stories, “Kaleidoscope” and “The Rocket Man,” and Bradbury himself wrote a letter to Gaines pointing the theft out. Improbably, that led to EC’s comic-book adaptations of other Bradbury stories.) Here’s the twist ending to “Home to Stay,” purloined from this website:

A child’s innocent wish juxtaposed with the death of a friend: Polyp ends with the same dramatic irony as “Home to Stay,” and feels to me more like a witty (but shallow) EC allusion than a poignant moment. Genre trumps emotion. I wish Polyp had ended with Hana and Asterios sitting on the couch, not speaking and their hands almost–but not quite–touching.

____________

Update by Noah: You can read the entire Asterios Polyp roundtable here.