The mellow mood of being on holiday has made me decide to shift tack from the more theoretical stuff I’ve been on about and instead dig into my archives for a post about a comic I love, and which despite its great fame bafflingly still seems virtually unknown in the English-speaking world. The article is a slightly edited version of a review I wrote back in 2005 for my website rackham.dk. I apologize for some of the scruffy scans and hope you’ll enjoy the piece anyway!

“Quino exists and Mafalda is his Prophet.” Those are the words the Argentine cartoonist Fernando Sendra has his best-known character, Matías, speak in an homage to his older colleague and countryman. It fairly precisely encapsulates the status enjoyed by Joaquín Salvador Lavado, better known as Quino (b. 1932), not just in his own country, but throughout the Spanish-speaking world. Quino, who made his debut in the mid-50s is today regarded as one of Latin America’s greatest cartoonists and his sophisticated satirical and gag cartoons indeed count amongst the best in their genres, but it was his comic strip about the small, critically insightful girl Mafalda and her friends that made him a household name beyond the borders of Argentina.

After an innocuous start as a never-implemented advertising campaign for a home appliance company, the strip debuted in the weekly paper Primera Plana in 1964; it moved to the daily El Mundo the following year, and upon the closure of that paper in 1967 ended up in the weekly Siete días in 1968, where it stayed until Quino decided to end it without further explanation in 1973, when it was at the height of its popularity and had emigrated into television and merchandizing. Quino has since continued his work as an editorial- and gag cartoonist, but has never returned to the strip format. In spite of this, generations of Latin Americans have grown up with Mafalda, which has been endlessly rerun and reprinted.

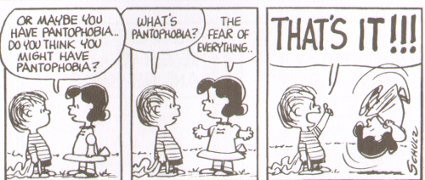

In the Spanish-speaking world the strip is considered amongst the greatest classics of comics and, because their obvious similarities, is often compared with Charles M. Schulz’ Peanuts, frequently to the disadvantage of the latter. Regardless of one’s personal preference in this matter, it is an apt comparison and Mafalda quite obviously occupies a similar position in Latin America to Peanuts in the United States and parts of Europe. Unfortunately, only over the last few years has it been seeing full publication in English, in a shoddily produced book series released by its Argentine publisher, to deafening silence.

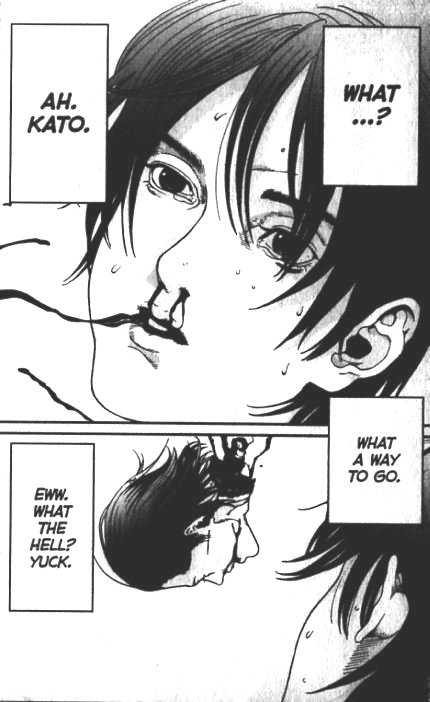

“Do you improvise or plan our upbringing?”

What kind of strip is Mafalda? It makes sense to start with its similarities with Peanuts. In its conception, it was obviously indebted to Schulz’ strip, conceived as it was along the same lines—small philosophical, poignant and funny incidents between a group of wise middleclass children—but the strip is clearly its own thing. Where Peanuts is a suburban strip, Mafalda takes place in the big city; where Peanuts exclusively focuses on its child characters, who stand-in for the adult world, the relationship between children and grownups is one of the central themes in Mafalda; Where Peanuts delivers its punchlines in an almost timeless environment, Mafalda continually comments on and critiques its time, although it does this without ever becoming acutely topical. At a more fundamental level, however, the strips are different in tone: Peanuts takes place in a sleepy no-mans land, where dreams and aspirations dissipate in the emptiness above the trimmed lawns and white picket fences, while Mafalda—though not without melancholy undertones—is warm, friendly and vibrantly immersed in life as lived.

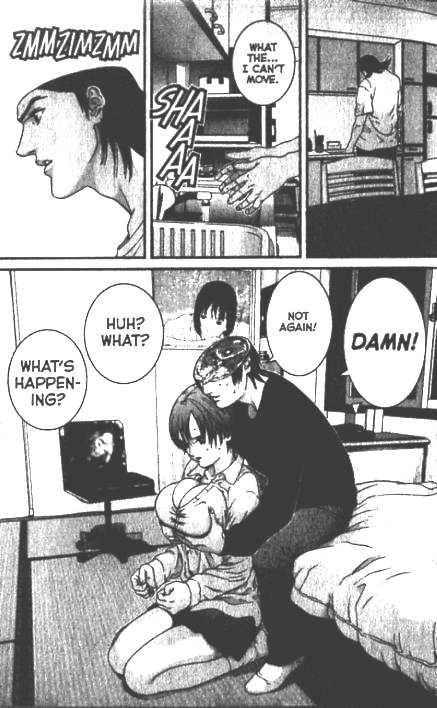

“All cops are nice”

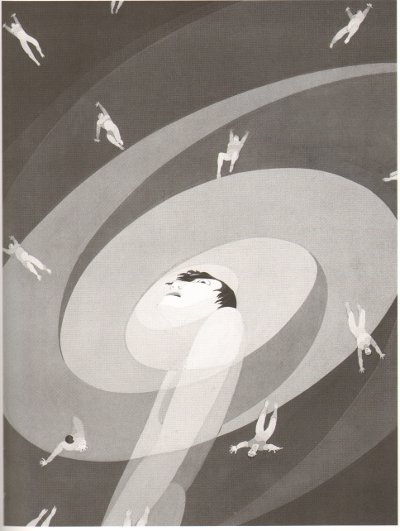

Mafalda is the child of a troubled moment of her homeland’s history. During the period Quino chronicled her daily doings, the country saw six changes of government, all variations on the military regime. Political violence was rampant and democratic overtures were few and far between. During this period, most of Latin America was plagued by political unrest and repressive governments, the war in Vietnam was escalating, the Chinese Cultural Revolution started, and the arms race between East and West was running at full bore. All of this is reflected in the strip, even if only occasionally mentioned directly, as is the spirit of 68, women’s liberation and the rise of youth culture, with the Beatles as an incontrovertible primary exponent. Quino is basically a disillusioned humanist, deeply skeptical of all kinds of authority, whether the brutal hegemony of capitalism or the crushing grip of communism.

“Just imagine how peaceful the world would be, if Marx hadn’t been served soup as a child”

And as mentioned, Mafalda is his prophet—she embodies her creator’s skepticism, his sense of justice and his indignation. She’s her “irrepressible heroine, who rejects the order of things… and demands her right as a child not merely to live as debris in the wreckage of the world of her fathers” as Umberto Eco—Quino’s first Italian editor—writes. But at the same time, she is human and therefore susceptible to the same weaknesses as everyone else. While the sweep of history provides subtext, her world is quietly quotidian—school, TV, play, holidays, etc. The big questions are reflected in daily reality by way of recurring motifs of conflict and cognition, such as her distaste for the soup insistently served by her mother; her naïve questions to her parents about the world at large, which invariably result in quiet embarrassment; the absurdities picked up from passersby when one sits on the curb in the sun, or from the radio; the multitude of ways a kid may confound a door-to-door salesman, etc.

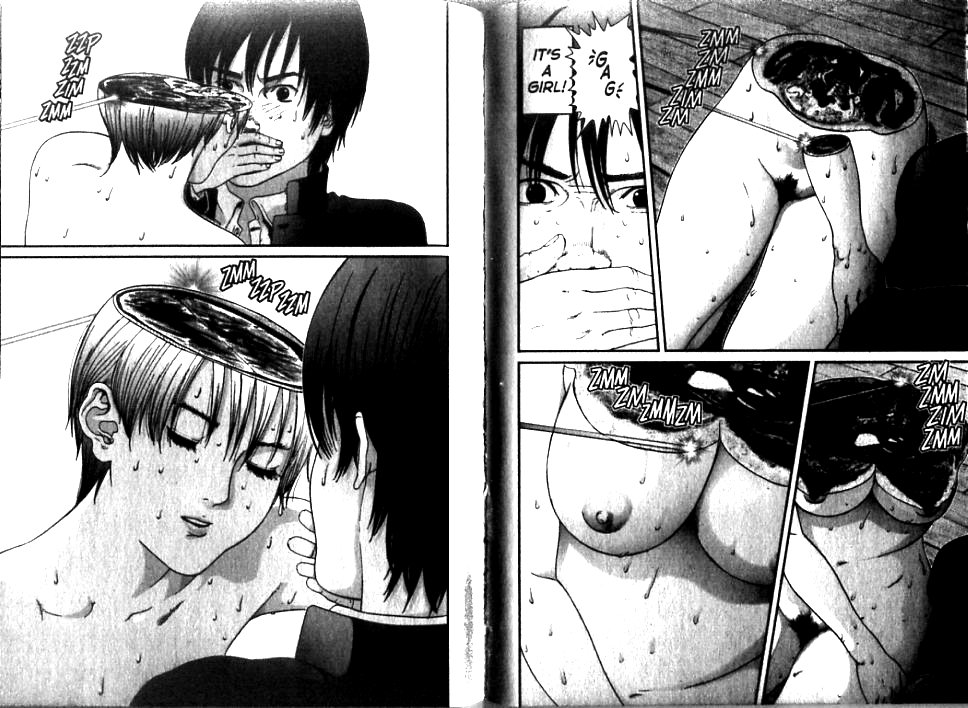

How you drive a door-to-door salesman crazy

Mafalda is the closest we get in the strip to ideal human representation, but as is typical in comedies of type, she is made whole only by the characters that surround her, which provide the spectrum of distilled human traits and qualities that make the work resonate. One of Quino’s masterstrokes is the introduction, about halfway through the strip’s life, of a little brother to Mafalda, Guille, who is manifestly anarchic in character of towards whom she is forced to reproduce the friendly but firm authoritarian disposition she herself encounters in her parents.

Mafalda ends up reproducing her parents’ reaction to the mercilessly inquisitive Guille.

Around the same time, we meet the tiny tot Liberdad, whose analytical sharpness and ability to see the Big Picture and always align herself with the People suppresses somewhat these traits in Mafalda herself and gives her more natural social insights room to breathe on the page.

Liberdad corrects her friends: money isn’t everything, but perhaps it is, after all, for those who don’t have it?

Liberdad corrects her friends: money isn’t everything, but perhaps it is, after all, for those who don’t have it?

In the circle of friends we also find buck-toothed Felipe, the perpetual dreamer and just as perpetual loser:

Characteristically, his greatest hero is the Lone Ranger, but when he plays cowboys and Indians with the other, more realistically disposed kids, things never work out as he had hoped. We do not know whether the attractive—attractive, we have no idea whether she is actually sweet—girl on whose blind side he suffers has red hair, but the relation to Charlie Brown is evident, even if Felipe—typically for the strip—is more actively engaged with life than his North American brother by another father.

Miguelito is a child of nature with a prodigious imagination—wherever he goes, he sees a magical, different world. He is fundamentally inquisitive and his thoughts on reality are original and unexpected:

“My mirror image evaporates and spreads a little of me all over the city”

Characteristically for Quino’s subtle approach, it is never spelled out just how devastating the presence of this little visionary must be for Felipe, whose imagination always comes up short:

Contrast: Miguelito and Felipe on their way to school.

And at the same time, without it ever being addressed, one sense that Miguelito’s rather loose grip on reality has its reasons: only a few times do we meet his neat freak mother—cleaning her way through life obsessedly—to whom visiting children feel like an invasion, and she remains off screen, but the contours of an unstable home are felt.

Another home of unarticulated tension is that of the slightly dense, overweight Manolito. He only rarely has time to play because he must help out in his dad’s grocery store. He works hard to imitate his hard-working immigrant father, and is clearly expected to do so. The result is a one-track preoccupation with business, which ultimately shuts out other aspects of life for him. Manolito is socially inept to a degree where he drives away his friends with his constant pitching for ’Almacén Don Manolo’ and the advertising he scrawls all over the city.

It makes sense that the character who has the hardest time with Manolito is the other socially awkward child in the group: Susanita, the prim, and rather dim, little bourgeoise. She represents the old order in the most square fashion, spending most of her time dreaming about her future husband and family life while avoiding anything that rocks the boat, whether it is the upstart capitalist Manolito or the Beatles.

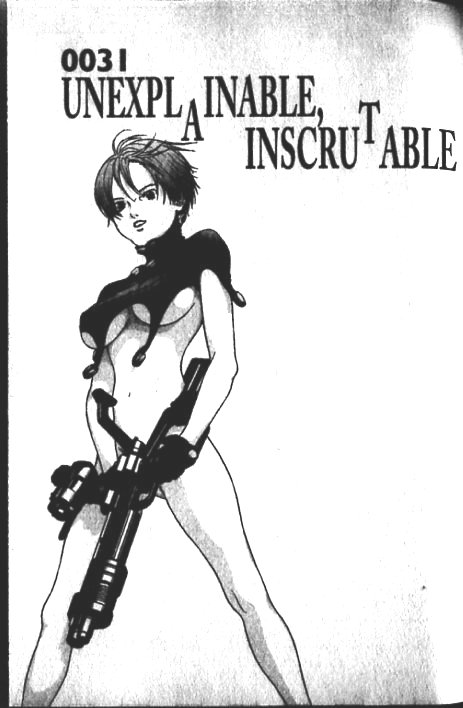

Susanita addresses women’s lib.

By such description of the characters, Mafalda might come across as rather bleak social satire, but far from it. Despite all their differences, the kids are friends and always end up accommodating each other. Quino’s belief in human beings as fundamentally social and moral is manifest. Mafaldas world—the local—is a benign community in a chaotic world and it is the belief in such community that makes Mafalda the humanist and idealist vision of society that it is.

At times, it flirts with banality—a recurring and slightly forced motif has Mafalda sharing the stage with a globe, which triggers all kinds of “poignant” and frequently rather trite observations about the madness of the world:

The world is sick, it’s hurting in Asia

At other times, it veers into the bourgeois—this happens especially when it describes small, cute episodes of family life. But most of the time, Quino maintains a level head, a sharp pen, and is very, very funny. His masterful character work is augmented by a refined sense of comic timing and dialogue:

It makes sense when he describes the cartoonists Sempé and Saul Steinberg as two of his main sources of inspiration, because his line precisely synthesizes central aspects of their very different approaches into an organically animated, personal “handwriting.” Sempé’s sweetness and cheek animates the sensitively captured facial expressions of Mafalda and her friends; his Parisian elegance is apparent in such details as a fugaciously suggested lamppost in the background of a park scene:

…while his atmospheric liveliness comes out when Quino draws the family’s messy, lived-in bathroom:

Quino has not only adapted his angular line from Steinberg, but also its intelligent use in the delineation of graphic elements such as the dexterous doodles Mafalda draw on the floor to denote her life:

…or the hatching on a policeman’s pistol holster, or the scrawl of inventive, messy childish graffiti on the angular, ordered walls of the family home, with their banally decorative paintings. Quino is conscious that every line, if drawn with attention, has its own life:

It is this vitality that stays with you as a reader of Mafalda, which focuses on the rejection by childhood of all forms of predetermination, insisting on free agency as essential. When the strip ended, Argentina seemed on course to better times with the return of the long-exiled former president and dictator, Péron, but the military coup in 1976 put an end to any optimism engendered by the new government and instead led the country into its darkest period in modern history. This happened without the companionship of Mafalda and one can only guess at Quino’s motivations. Beyond the basic wisdom of quitting at the height of your powers, his decision might indeed reflect the strip’s insistence that the world can be a better place and that the choice is in our hands. An insistence that makes eminent sense amongst children and which is too important for us to let it weaken as we grow older, into disillusion.

“In thirty years, the world will be a much better place, because we, the children, will rule.”