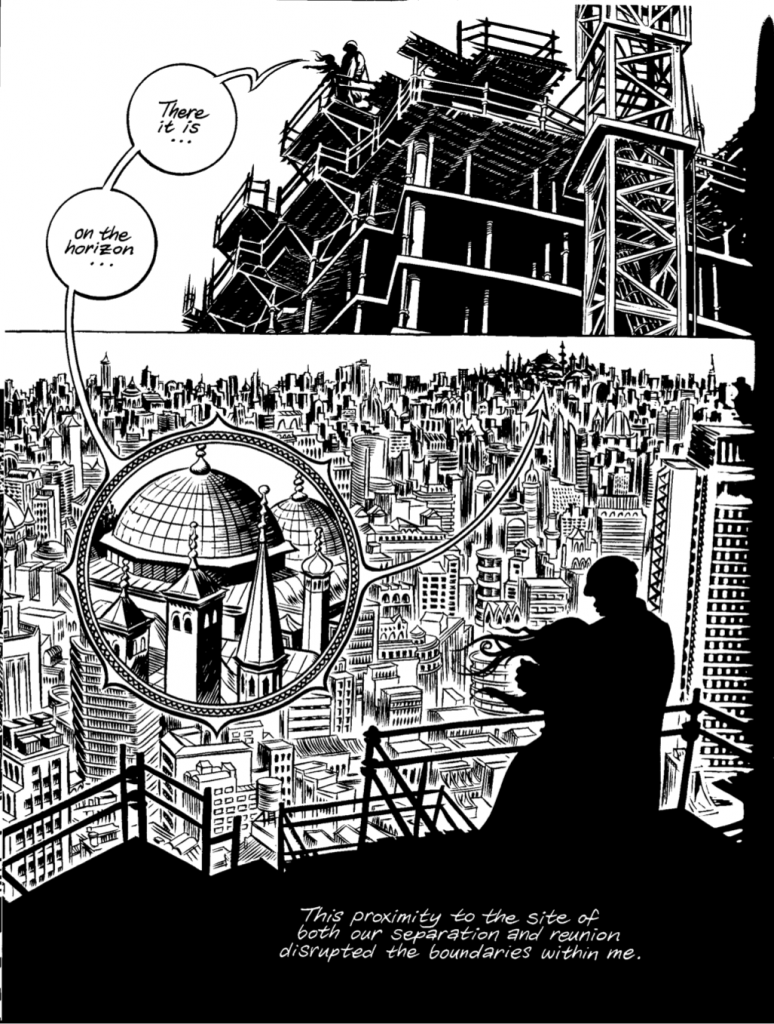

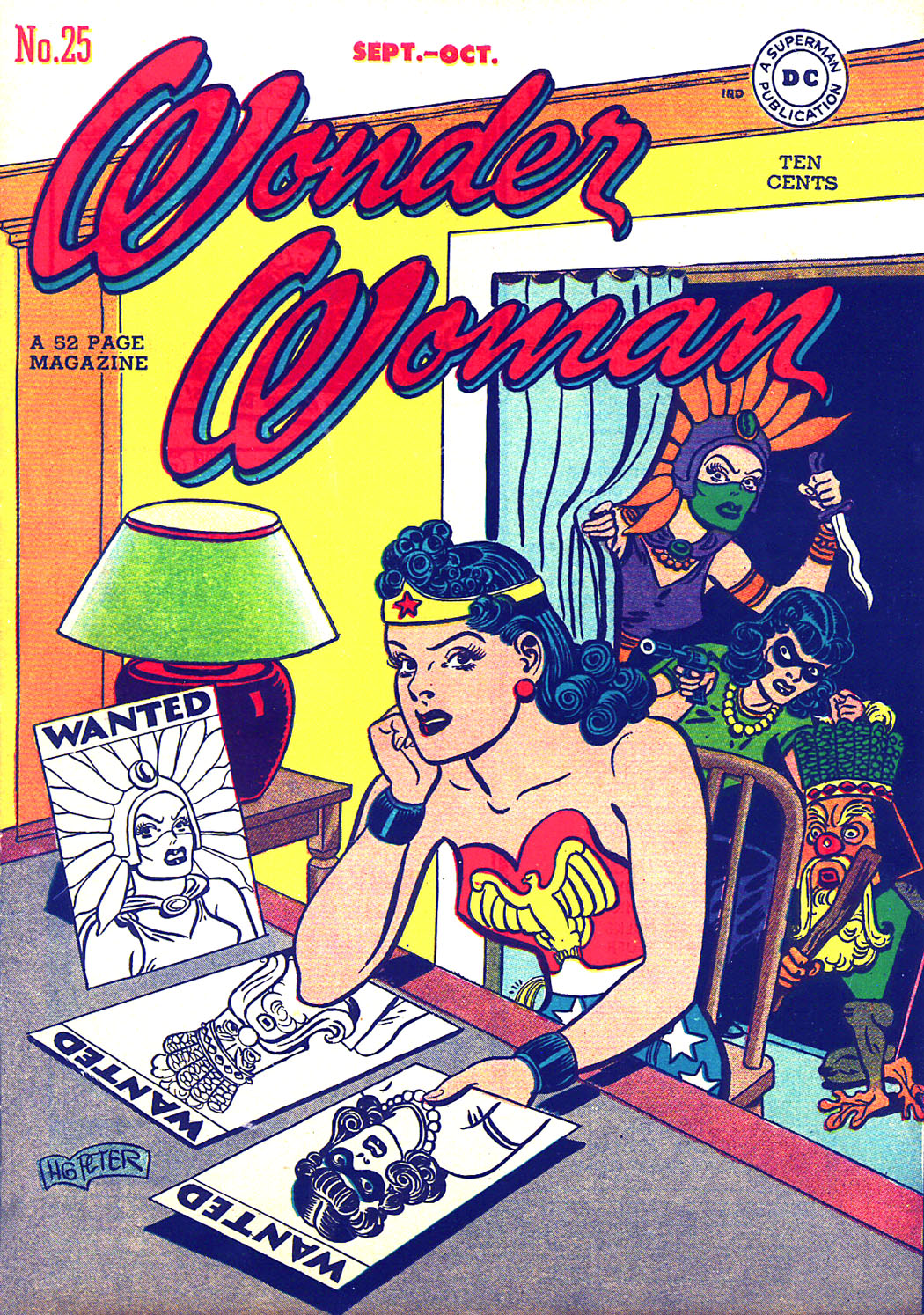

Sina Evil is a comics artist, best known for his self-published autobiographical comics series BoyCrazyBoy. He is also completing aPhD on the history of queer comics. He is a huge fan of the Golden Age Wonder Woman. His website is www.boycrazyboy.com.

This paper was originally given at Transitions 2: New Directions in Comics Studies”, a symposium at Birkbeck College, on Saturday November 5th 2011. It is the first of two posts on Gay Ghetto Comics. The second is scheduled to appear next week.

______________________________

This post focuses on North American gay comics, especially the sub-genre I call “gay ghetto” comics. In this post I will discuss the ways in which gay ghetto comic strips construct a dominant gay habitus, representing the gay community as relatively stable and unified; and, related to this, how certain types of gay male bodes are represented as desirable and acceptable – as representing a “typical” gayness – whereas others are devalued and excluded.

The Gay Market

In her book Business Not Politics: The Making of the Gay Market, Katherine Sender explores how the professional routines employed by lesbian and gay professionals working in media and marketing serve to shape the ways in which LGBT identities and the LGBT community are represented in media images.

The gay community and gay culture are often perceived and represented as unified and homogeneous, both by people “outside” of LGBT communities and those “within”. However, because of differences in terms of (at the very least) gender, race, class and generation, the tastes and practices of LGBT people are segmented into a number of discrete and overlapping clusters. Yet as Sender emphasizes, “each of these clusters does not have equivalent opportunity to appear as – and speak for – the gay community” (2004: 15).

Sender draws on Bourdieu’s concept of the “habitus”, which describes how tastes shape the relationship between the body and its symbolic and material contexts; “Habitus embodies the lived conditions within which social practices, hierarchies, and forms of identification are manifested through an individual’s choices, but signals that those choices are already predisposed by an existing social position” (2004: 14).

Sender argues that the most visible and socially sanctioned gay collectivity is not particularly diverse in terms of race, class, and to some extent gender: “This constituency is identified in part by its participation in a dominant gay habitus” (p. 15). The identities and practices associated with a dominant gay habitus are displayed “in bars, music clubs, parties or on the street” (Fenster: 1993, 76-77). They are also represented in cultural products such as magazines, advertisements, films – and comics.

In his essay on queer punk fanzines, Mark Fenster (1993) argues that dominant positions within gay communities tend to be held by “middle class adult homosexuals who are more assimilated within dominant economic and social structures”, and who are thereby better equipped to represent themselves and to circulate those representations through various forms of commercial media (p. 76-77).

The gay habitus constructed through marketing and in gay publications serves to make visible such gay and lesbian individuals – that is, those who are already otherwise empowered. Sender argues that gay marketing practices focus on members of a dominant gay habitus, obscuring the less “respectable” – and therefore less marketable – members of the LGBT communities, including people of colour and poor and working-class queers.

Sender argues that such conditional visibility effectively limits the choices LGBT people can make without forfeiting their visibility, and occludes the diversity of LGBT communities. Media images of LGBT people not only structure a visibly gay consumer culture, “but also how the participants in that culture are seen” both by heterosexuals and – in many ways more importantly – within LGBT communities (2004: 138).

Such media images depend on “representational routines to construct a recognizable gayness” (p. 123) such as “using recognizably ‘gay’ or stereotypical images, showing same-sex couples, using gay iconography, and making appeals to gay subcultural knowledge” (p. 124). Precisely because being gay does not always show, gay cartoonists have wielded the same or similar signs and symbols in order to construct recognizably gay characters in a recognizably gay cultural and social milieu.

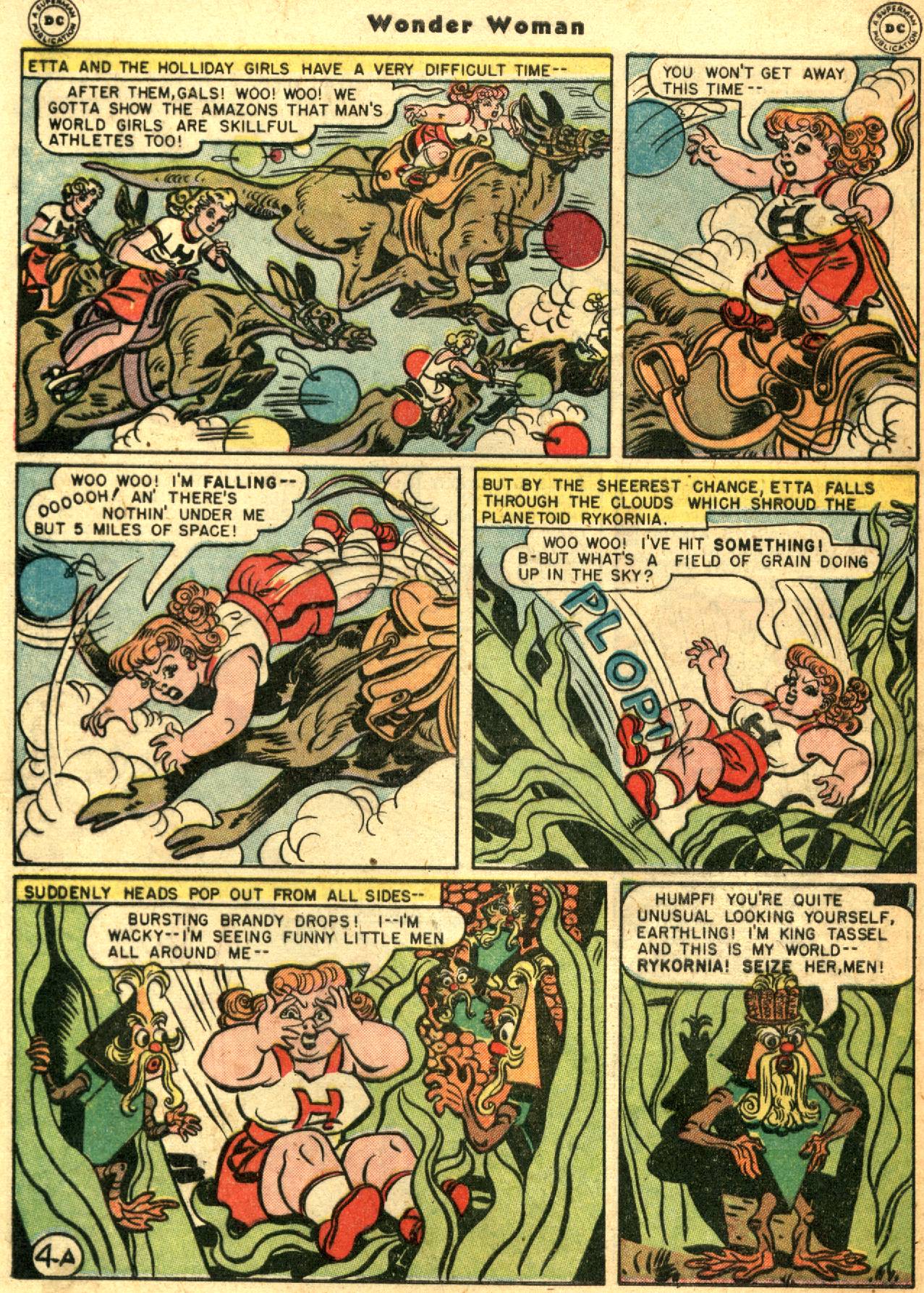

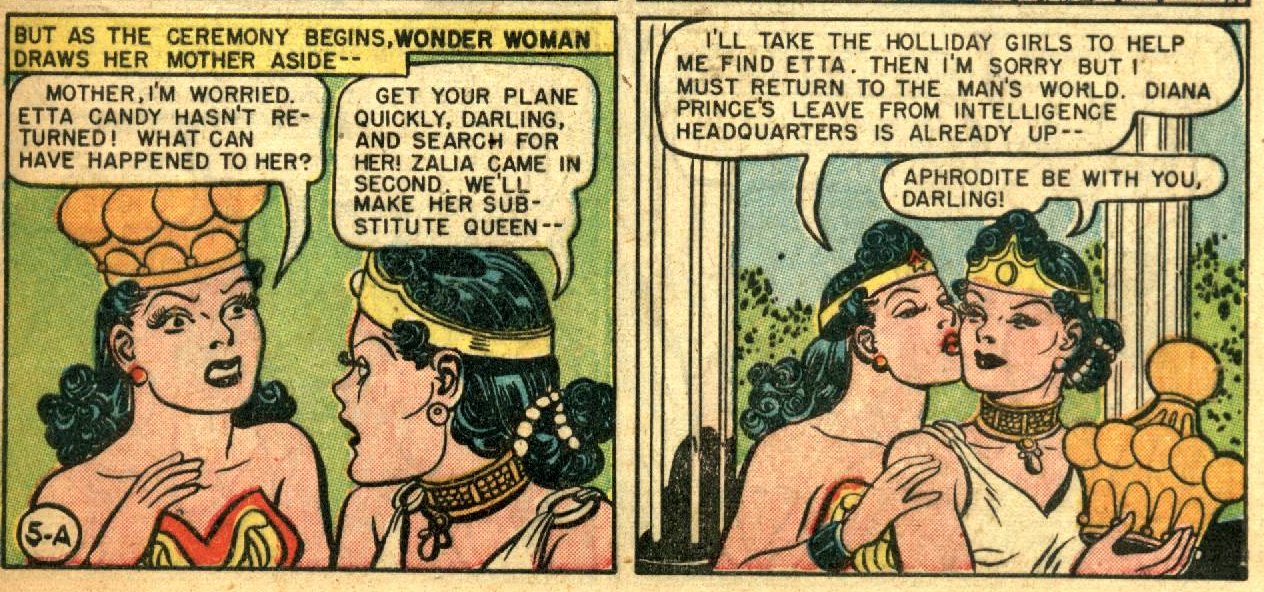

“Gay ghetto” cartoons and strips serve as an archive of such gay signifiers – locations, fashions, body types, slang – all of which may be deployed to convey an invisible sexuality. Gay ghetto cartoons and strips started to appear in early gay newspapers and magazines from the 1960s onwards, with a wider range emerging throughout the 1970s and 1980s as more gay magazines were published throughout the United States. Indeed, many gay ghetto comic strips continue to be published today either in commercial gay magazines as well as, increasingly, online.

The Gay Ghetto

Gay ghetto cartoons and strips are often set in a recognizably “gay” location – one of the well-known gay urban enclaves in major (usually American) cities, such as West Hollywood, LA, the Castro, San Francisco, and various Manhattan gay neighbourhoods including Chelsea and Greenwich Village. The explicit or implied locations of gay ghetto comic strips are of course the first important signifiers that signal that this comic is gay, since certain urban centres – San Francisco, LA, New York in particular – have come to “stand for” the “gay community” in the popular imagination of Americans particularly (Chasin 2000: 169).

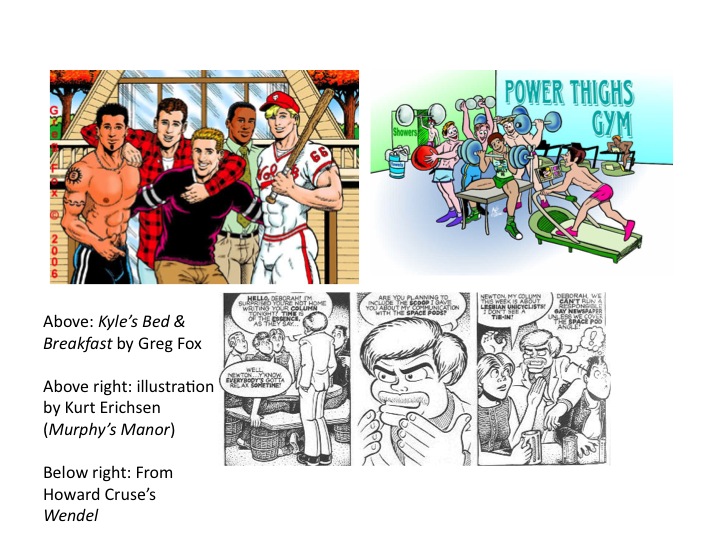

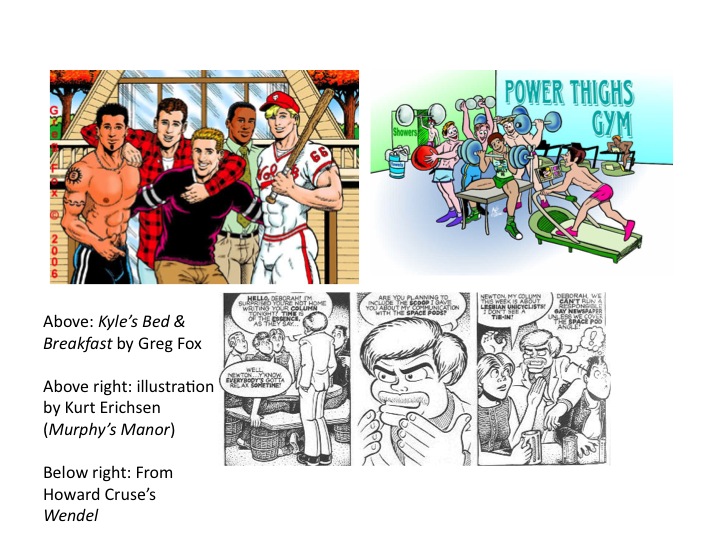

The main action in “gay ghetto” comics tends to take place in and around certain “gay community” institutions – a gay boarding-house (as in Kurt Erichsen’s Murphy’s Manor), a gay bed-and-breakfast (Gregg Fox’s Kyle’s Bed and Breakfast), the offices of a gay news-magazine (Howard Cruse’s Wendel), as well as gay bars, gyms, dance clubs, beaches, bathhouses, and Gay Pride festivals (many of the strips.) Characters in gay ghetto comics will often use gay slang when speaking to each other, and the strips will include both verbal and visual references to various gay “types” or “tribes” such as gym queens, drag queens, leather men, bears and so on.

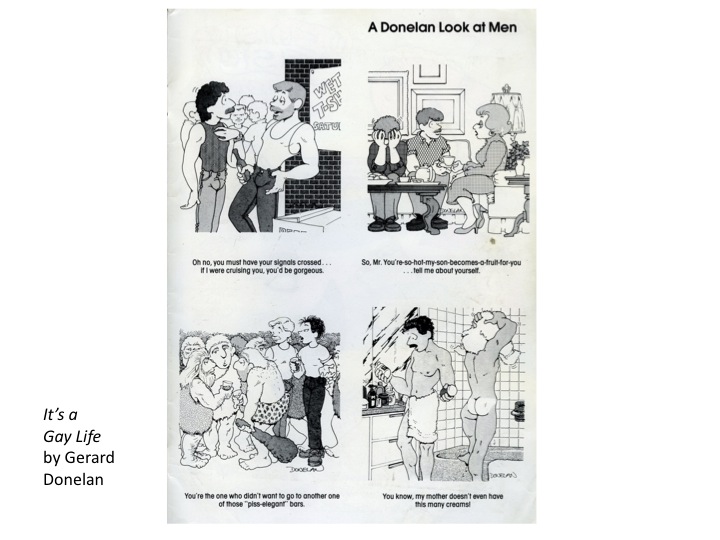

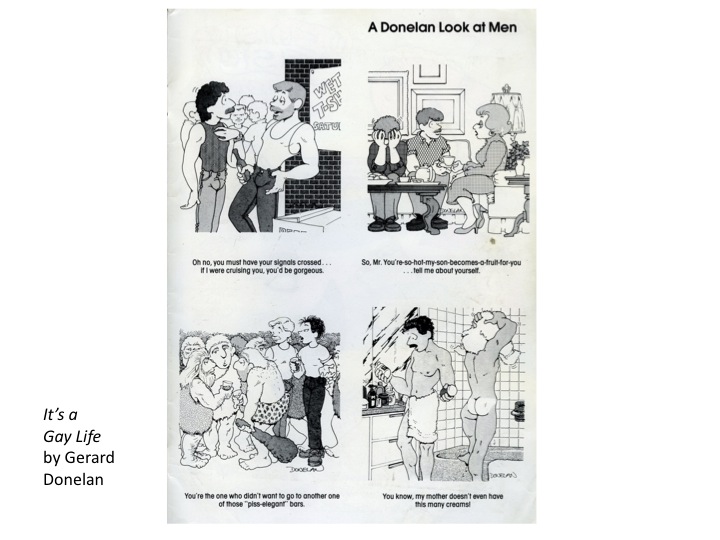

Gerard Donelan’s It’s a Gay Life cartoons are an early example of the gay ghetto genre: they feature gay men who are for the most part young, white and middle-class, and conventionally attractive and fashionable in accordance with the dominant gay trends of the late 1970s and the 1980s; the characters typically tend to be portrayed hanging out in gay bars and dance clubs, going shopping, and in private spaces such as the homes of domesticated couples or casual sex partners. The captions accompanying Donelan’s single-panel illustrations tend to parody or make reference to stereotypically “gay” preoccupations with cruising, fashion and body image, and humorous sexual scenarios – that is, all of the signifiers of a commodified gay identity and lifestyle as it emerged in the urban enclaves of American cities in the 1970s and throughout the 1980s.

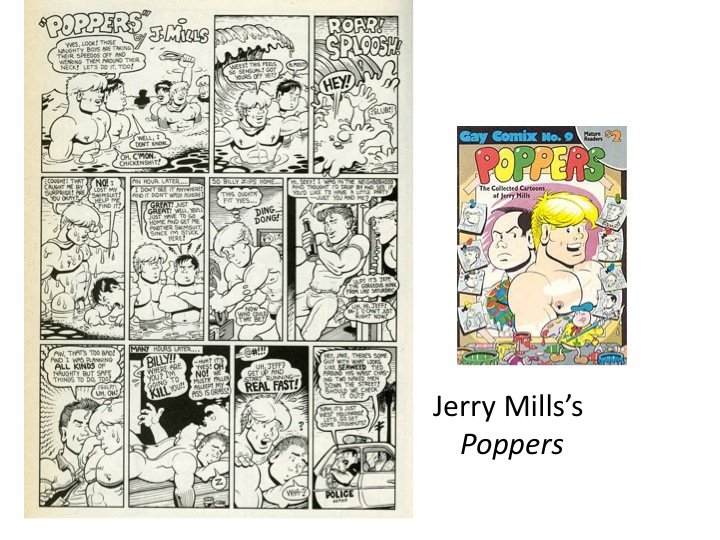

Cartoonist Jerry Mills writes that “Donelan captured perfectly the smugness and self-satisfaction that later came to be known as the ‘clone look,’ but done with affection, not malice” (Mills 1986: 11). The affection – noted by Mills – with which Donelan depicts the gay milieu he focuses on, is one of the most prominent features of the “gay ghetto” sub-genre; this affectionate portrayal of the gay ghetto and its mores is apparent in the majority of cartoons and strips that began to appear in gay and lesbian publications from the 1960s, and into the 21st century.

The focus of the gay ghetto comics is on the creation of an emphatically and openly gay culture that is often positioned against dominant heterosexual culture; as Sewell describes in his essay “Queer Characters in Comic Strips” (2001), characters in these strips are sometimes shown feeling uncomfortable with having to hide their sexuality in the straight world, and experience their gay community as a place of refuge but also as a space where problems like internalized homophobia can be discussed. In spite of such confrontations and disagreements between characters in gay ghetto strips, the characters in these gay micro-communities are ultimately represented as being very much “at home” with one another and within their specific social milieus. The gay community in these strips tend to be represented as something of a haven, in contrast with the “straight world” – a place where one is safe, where all members of the community – underneath any conflicts – essentially understand and support one another and where disagreements over contentious issues, “far from being dangerous or destructive, enable the community to develop and to improve itself” (Sullivan 2003: 137). Here the gay community – and the concept of “community” more generally – is represented as “a safe place you share with others like you, a ‘home’” (p. 137) – sometimes quite literally as in Kyle’s Bed and Breakfast.

“Typical” Gayness and Its Discontents

Through all the signifiers and codes discussed, these comics construct a dominant gay habitus, a visible and “typical” gayness. In doing so, these strips also naturalize and reify certain (culturally and historically specific) gay scenes, lifestyles, and mores as exemplary of “what the gay community is really like” – and hence they present an image of the gay community – and gay identity – as relatively unified and stable. They also, often, represent an idealized version of the gay male body as typical, valuable and desirable, while often marginalizing or devaluing gay male bodies that fail to conform to this ideal.

It must be emphasized that all of the “gay ghetto” comics are by no means homogeneous or uniform in their approach to representing gay community, and are rarely altogether simplistic. A number of these strips feature characters who are depicted at times as feeling uncomfortable within their community. Interestingly, this discomfort often revolves around the characters’ issues around body image, beauty and sexual confidence, and what gay critics like Michelangelo Signorile have referred to as the “body fascism” of the gay male scene – that is, the conformity demanded to certain activities that Michel Foucault might describe as “disciplinary regimes” or “normalizing practices” – activities such as gym routines, dieting, waxing and shaving the body, as well as other fashionable body-management practices.

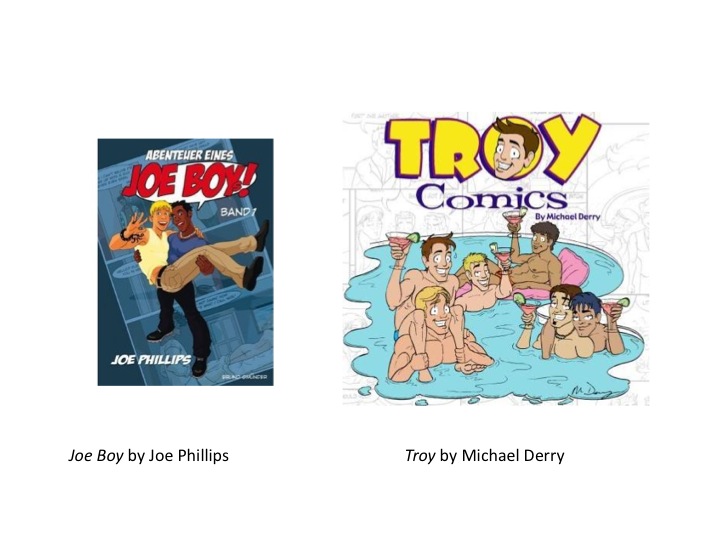

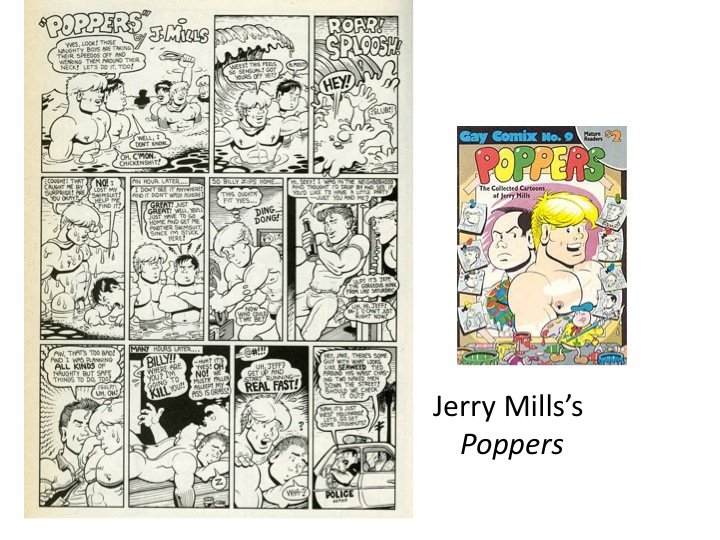

Yves in Poppers, Nathan in Chelsea Boys, and the eponymous main character of Troy are affected by mainstream gay culture’s body fascism to varying degrees. Yves, Nathan, and Troy are depicted as less confident and/or less fashionable, and possessing less athletic physiques, than most of the other gay characters in their respective strips. In each of the strips, these “average” characters stand in counterpoint to a much more sexually confident and/or conventionally attractive character – blonde hunks Billy and Sky in Poppers and Chelsea Boys, respectively; Latino bartender Rigo in Troy. These more confident and attractive characters are usually muscular and above-average in height, smooth rather than hairy, and tend to dress in a “typically gay”, fashionable way. In many strips, the more beautiful, sexually confident characters embody the qualities that the less confident, less stereotypically attractive characters aspire to possess, or wish they were like. Sometimes they try – and fail – as in the Poppers story in which André dyes Yves’ hair blonde and advises him to “act blonde” in order to compete with Billy; ultimately however Yves fails because, as he puts it, André “forgot to dye my brain blonde!”

All of the principal characters in Troy engage in Focualdian disciplinary regimes of going to the gym, and they all have muscular bodies. Troy’s eponymous lead character is by no means “unattractive” – he is represented as slim and fit, but never the less is shown in early strips feeling anxious that he is not “hot” or “buff” enough to attract sexual partners or a boyfriend.

Over the course of the strip he is shown going to the gym and beefing up so his already fit physique matches the muscled bodies of virtually all the other characters in the strip. Troy’s friend, bar-boy Rigo, is portrayed in early strips as handsome, extremely muscular, and hence very sexually active; however, in later strips he is shown gaining weight and because of this is portrayed as not being “hot” enough to attract the many sexual partners he had previously enjoyed. Rigo’s new belly – a sign of his lack of discipline and failure to manage his body – is portrayed as a source of horror and disbelief not only to himself but also to the other, slim, muscular characters in the strip.

A similar attitude to the gay male body is evident in many stories by Joe Phillips, collected in his Joe Boy books. The story “Club Survival 101” follows its main character, college guy Cam, as he visits a gay club for the first time, where his friend Trevor sees him, and is quick to criticize the way he is dressed. A stranger comes up behind Cam and leads him to a back-room where a complete transformation of hair and clothing takes place, before Cam is returned to the dance floor.

In his essay “Queer Characters in Comic Strips”, Sewell praises the story for depicting the central character’s transition from straight to gay culture; as well as being “restyled and recreated into an appropriately queer image that fits into the queer club scene”, Sewell writes, Cam now also “behaves in a manner appropriate to the gay club scene” (2001: 266). For Sewell, “Club Survival 101” is an authentic and accurate depiction of gay male experience and identity.

However, Phillips’s strip could be interpreted quite differently, as a glorification of the dominant gay habitus and propaganda for its normalizing disciplinary regimes. The “gay world” represented in “Club Survival 101”, populated by youthful, slim and/or muscular, fashionable (and predominantly white) clubbers, is not so dissimilar from the glossy, marketable images of the gay community found in the advertising and editorial of numerous other gay magazines. Sewell is correct to point to the important role played by clothing in queer subcultures; however the story “Club Survival 101” does not simply document a variety of existing styles but actually functions as an advertisement for a specific fashion retail company – at the bottom of the last page of the strip is the notice: “Character clothing and merchandise can be found at http://www.xgear.com”, an especially blatant example of “product placement” within a comic. It is not particularly surprising that is happens in a gay comic commissioned by and published in a glossy gay lifestyle magazine like XY, which like the majority of fashion and lifestyle magazines (gay or not) exists primarily to provide a “nurturing environment” for its advertisers. The strip is essentially an advertisement for fashionable clothes aimed at young gay men.

If a character in the Joe Boy comics does not conform to the dominant gay habitus they are either “clueless” and simply in need of a makeover; otherwise they are doomed to be mocked for not being fashionable, ignored because they are too fat, and/or stood up by their dates – and this is all presented as “fun”. What Signorile describes as “body fascism” is presented as the norm in Joe Phillips’s comics.

Alternative Gay Comics

Gay ghetto comic strips have existed since the 1960s and continue to be published to the present day. However since the late 1980s and particularly the early 1990s other, alternative gay comics genres have also emerged.

Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s various queer people felt alienated from the “official” gay and lesbian community and culture – but nevertheless desired some sort of gay community/culture. In the late 1980s and early 1990s many of these people responded to their feelings of frustration and exclusion by creating their own culture and a variety of different media – this came to be known as the “queercore” subculture. By the early 1990s a number of LGBT cartoonists began to emerge against the background of the new, often aggressive, “queer” approach to identity and politics, and influenced by the alternative comics and zine scenes that had been growing throughout the 1980s.

Often feeling that their work would not “fit in” with the glossy, mainstream gay magazines, and inspired by the burgeoning zine culture’s “do-it-yourself” ideals, new LGBT cartoonists began to produce and distribute their work through self-published comics or small independent presses. These cartoonists were of course critical of homophobia, but far less interested in affirming a sense of shared gay identity and community, and much more concerned with focusing on their personal lives and identities, with critiquing mainstream gay culture as conformist and commercialized, and with creating alternative visions of gay and/or queer life and culture.

Gay alternative cartoonists take three main approaches to representing and critiquing the mainstream gay community. Firstly, many cartoonists would set their narratives outside of any recognizable contemporary gay context, thus avoiding depicting the gay scene directly – by setting their stories in mythic, fantastical or surreal contexts.

This second main approach to dealing with the gay community involves representing the gay community – either using fantastic metaphors or more directly – in a more or less negative light. Whereas the gay ghetto comic strips mocked gay culture with affection, from an “insider’s” perspective, gay alternative comics present much more pointed, satirical, often caricatured representations of “mainstream gay clones”, created from the point of view of artists who very clearly see themselves as “outsiders”, who are rejected by gay culture and therefore reject it. These comics are clearly motivated by the desire to present a more serious, substantive critique of gay culture than the gay ghetto cartoonists do. The cartoonists who portray gay culture in this negative light will also often simultaneously present an alternative vision of gay life: this is the third main approach gay alternative cartoonists take, and is often done by depicting small groups of queer characters who are not presented as “typical” of the entire LGBT community, who do not “stand” in some way for the whole community in microcosm (as is often the case with comics set in the gay ghetto) but are intended, rather, as distinctive, quirky, localized, and idiosyncratic, intended to tell personal rather than universal gay stories. Many of these comics will focus on quirky, “nerdish” gay “outsiders” – characters who feel alienated from the mainstream – and their adventures on the margins of the dominant gay culture.

Just as the gay comics of the 70s and 80s worked to construct a dominant gay habitus, the independently-produced comics that emerge in the 1990s strive to create an alternative.

Bibliography

Chasin, Alexandra, Selling Out: The Lesbian and Gay Movement Goes to Market, New York: Palgrave, 2000.

Fenster, Mark, “Queer Punk Fanzines: Identity, Community, and The Articulation of Homosexuality and Hardcore”, Journal of Communication Inquiry, vol. 17, no. 1, Winter 1993.

Mills, Jerry, “Introduction” in Leyland, Winston, ed., Meatmen: An Anthology of Gay Male Comics, Vol. 1, San Francisco: GS Press/Leyland Publications, 1986.

Sender, Katherine, Business, Not Politics: The Making of the Gay Market, New York and Chichester: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Sewell, Jr., Edward H., “Queer Characters in Comic Strips” in Matthew P. McAllister, Edward H. Sewell, Jr., and Ian Gordon, eds., Comics & Ideology, New York: Peter Lang, 2001.

Sullivan, Nikki, A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003.

Kyril Bonfiglioli’s All the Tea in China and Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang are both rollicking adventure stories set in the past when men were men and skullduggery was a rip-roaring adventure rather than disreputable thuggishness.

Kyril Bonfiglioli’s All the Tea in China and Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang are both rollicking adventure stories set in the past when men were men and skullduggery was a rip-roaring adventure rather than disreputable thuggishness.