Jean-Luc Godard celebrated his 81st birthday on Saturday, December 3. Last year, for his 80th, he got a font. This year, the Internet rather quietly (and capitalistically) observed the occasion: Criterion’s Facebook feed sent me to their summary page. The New York Times reviewed Histoire(s) du Cinema, and alerted me to its US DVD release on this Tuesday (Dec 6). Theaters announced special screenings. Assorted cinephile bloggers wished him well, of course, with the expected “best Godard films” lists and links to clips, my favorite of which was this short film entitled “Meeting Woody Allen”, which I’d not known about previously.

Here at HU, he gets a roundtable. Bon Anniversaire!

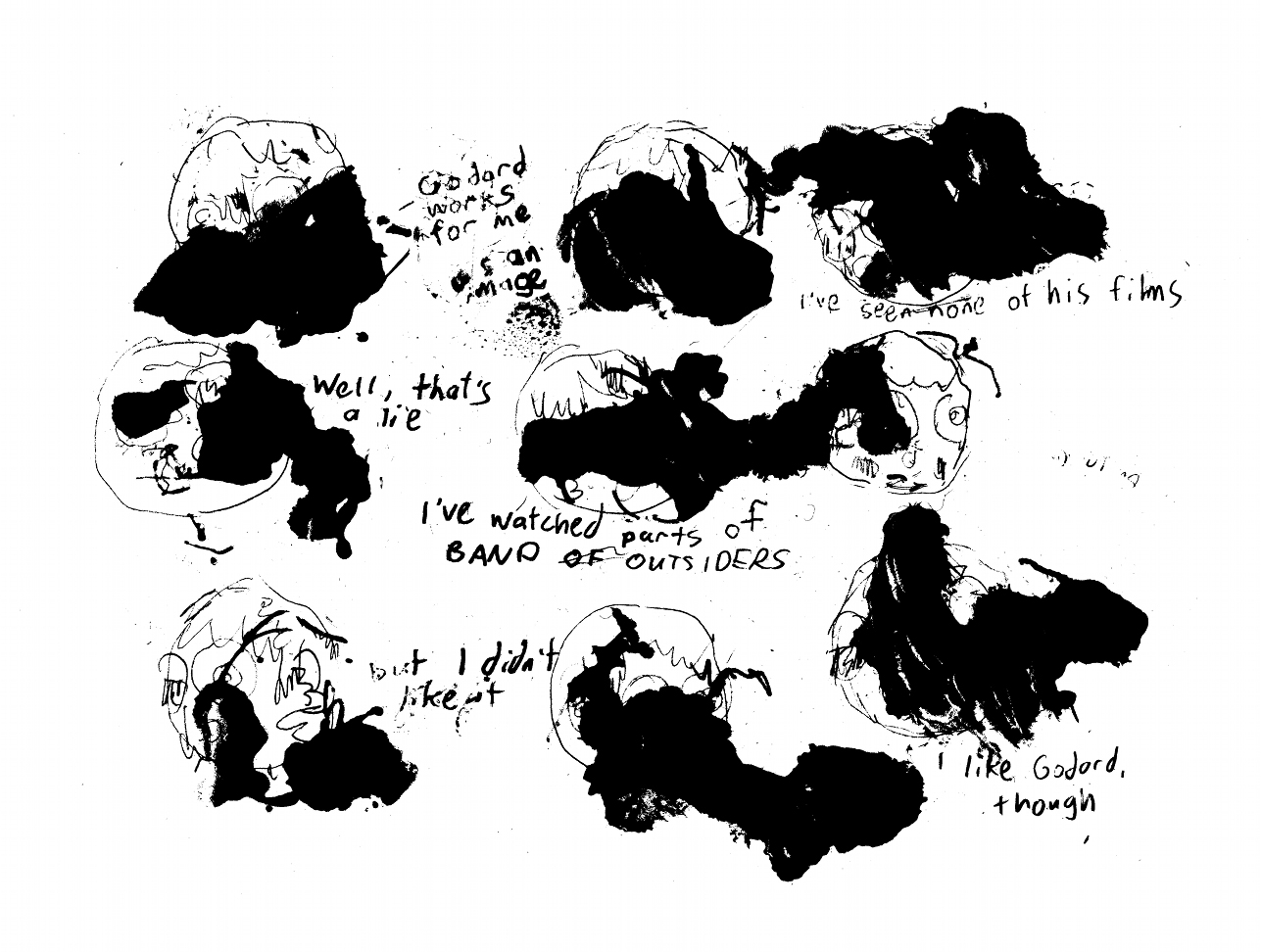

Godard is, perhaps more than any other filmmaker besides his contemporary and friend Luis Buñuel, driven by ideas – ideas of what the cinema is and what it is for, ideas about society and subjectivity, ideas about love and art. For many movie lovers, his work is excessively abstract, even opaque; his characters, distant and cold; his dialogue stylized, melodramatic. But to be a fan of Godard is to recognize the idea of humanity in his abstracted depiction of it, and to feel so much passion for the idea that the abstraction can stand in for traditional characterization and plotting without any loss of affect.

Perhaps more than any other filmmaker besides David Lynch, Godard is masterful with metatext, with constructing layers of meaning, with crafting signification from juxtapositions and the interplay of images, themes and words. For me at least, Godard’s own historical moment is always one layer of this metatext – perhaps the most important layer – the ideas in his films are French ideas, ideas fomented in the aftermath of war and occupation and in the tensions of the Cold War and its propagandistic ideological context. The images in his films are refracted through a French glass. “Godard” is a tapestry woven from Sartre and Bazin and Balzac and Buñuel and Lacan and Levi-Strauss and Althusser and Barthes and Langlois and Flaubert and Malraux. Godard, personally reclusive, enigmatic, and even secretive, became in his work a precipitation of the 20th century’s arguably most vibrant intellectual-artistic movement.

More than any other director most people have ever heard of, Godard is himself an idea – an idea of Art, an idea of commitment to Art, an idea of purpose for Art. Like many other French directors, he is in love with the idiosyncratic expression of “l’humanité”, witty and eccentric. Throughout his oeuvre he turned the rabidly individualistic notion of the “auteur” on its head: although his vision is uncompromising and uniquely his, it is impersonal and philosophical, concerned with humanity as a collective, with common humanity, human society, the conflict between man and society — and the necessity of subjective eccentricity, of Art and of desire, as an antidote, a balm, a cry in the wilderness first of post-war existential trauma and then of late Capitalism. Unlike Truffaut or Hitchcock or Scorsese, Godard is neither a personality nor even a body of work; Godard is a figura for art itself.

The title of this roundtable, “Qu’est-ce que c’est Godard?”, is a loose reference to the final line of Godard’s first film, Breathless: “Qu’est-ce que c’est, ‘dégueulasse’?” The quote is always a source of confusion for English translators — there is no English translation that captures the rich ambiguity of the French “dégueulasse.” Translations always end up resolving the multiplicity of meaning in the scene. “Godard”, like “dégueulasse”, is ambiguous and multiple, idiomatic, and somewhat impossible to translate. Each translation says as much about the translator as it does about the original. So will it be with this roundtable. Jouissez sans entraves!

*A couple of people have commented on the use of “Bonne fête” to mean “happy birthday”. It’s apparently Canadian only and doesn’t sound quite right to Continental Francophones. But I’m American — I’m sure my accent is even worse than my word choice!

Roundtable Contributors

Visit the Roundtable Index for a running list as contributions are posted.