So for those who don’t remember…more than a year ago I had written a series of posts about gender in comics. The basic argument is that a character like Superman is a male power fantasy. That fits in with Freud and the Oedipal conflict. Clark Kent can be seen as the “child” who imagines himself supplanting the Father/lawgiver/god. You can also take this one step away from Freud and argue (via the theories of Eve Sedgwick) that what we’re talking about here is not, or not solely, an internal psychological desire, but rather a cultural/social formulation. Men turn away from femininity in order to identify with patriarchal power; or, to see it another way, to be patriarchal requires the denigration or hiding of weakness.

That’s the closet; Clark Kent is living a lie, pretending to be powerful in order to be powerful, when his truth is actually a weak, wimpy child. And, again, the closet is powered by male-male desires and fantasies, making it homoerotic (though, as I argue at some length, it’s actually a straight person’s homoerotic fantasy — we’re talking about how straight men bond or interact with the patriarchy in particular, and arguing that that interaction is structured by ideas about, and within, gayness.)

I then talked about how the early Marvel titles messed with this formula. Characters like Spider-Man and the Thing were much more ambivalent about power; the superdick in them often becomes a devouring ogre (see The Hulk). You also see this in some super-hero satire, like Chris Ware’s Superman character. I argued, though, that the basic binary remains; these stories don’t reject the superdick. Weakness is still sneered at; it’s just that the anxiety around the superdick is greater. You want it but when you have it you don’t want it, and then when you don’t have it you want it again. I also noted that the fascination with power and the denigration of weakness ends up making superhero stories essentially sadistic (as opposed to horror, which works in a more masochistic mode.) This also makes it very difficult for superhero comics to create anti-status quo storylines. However anxiously, the law is always worshipped.

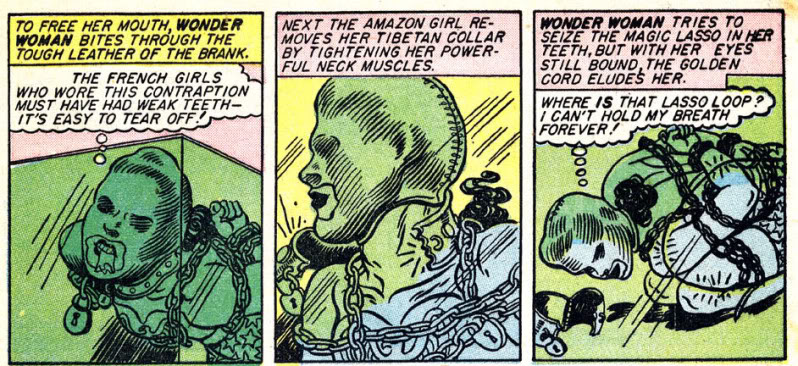

I then went on to talk about the way this relates to Wonder Woman. In particular, I argued that the anxiety and bifurcation of male identity doesn’t really work for Wonder Woman. Female identity is not seen as doubled in the same way; women are not split between patriarchal power and weakness. That’s because female identity is simply identified with weakness. Male writers of Wonder Woman like Kanigher and Martin Pasko tended to create narratives which were about robbing Wonder Woman of her power. There was anxiety around WW’s superdickishness, but much less so around her weakness. As long as she wasn’t in control, everybody was happy. You often got the sense from the books that nobody could figure out what Wonder Woman was doing with superpowers in the first place.

Of course, Wonder Woman had superpowers in the first place because William Marston gave them to her. Which is where we left off, and where I’m going to try and pick up now.

_________________________

One of the things I’ve mentioned a number of times in various Wonder Woman posts is that her secret identity doesn’t really work right. It’s a gender problem; superhero identities, as I indicated above, are supposed to be split along the frightened child/superdick Oedipal fissure.

Typically, superhero origins work like this; little Melvin Microbits is toddling along minding his microstuff when suddenly — transformative trauma! He is castrated by a radioactive giant tubular marine mammal! Quickly, miraculously, he grows a thing bigger than his dad ever had and decides to serve the Law as — Walrus-Man!

Or that’s the general idea, anyway. Batman’s maybe the most paradigmatic example (small boy, dad shot, takes dad’s place while still also remaining traumatized child.) It works for Superman too, though (baby, father dies, takes dad’s place while still also remaining puny child). And for Spiderman (young man, father-figure dies, takes dad’s place while still also remaining traumatized child.) There are some variations, like Green Lantern (young man, father-figure dies, takes dad’s place while still remaining asshole); or the Hulk (wimpy guy, traumatized, takes dad’s place while still also remaining wimpy guy.) But the general outlines remain discernible. It’s a meme.

But Wonder Woman’s origin doesn’t work like that. She’s born (or magically fashioned, actually) with super-powers. Her secret identity, Diana Prince, isn’t the “real” trace of the traumatized child she was and remains. It’s just an act.

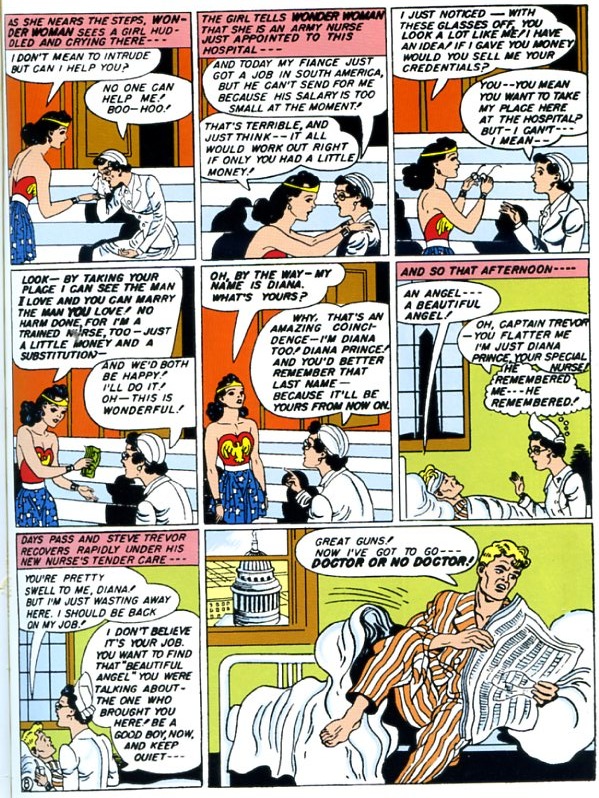

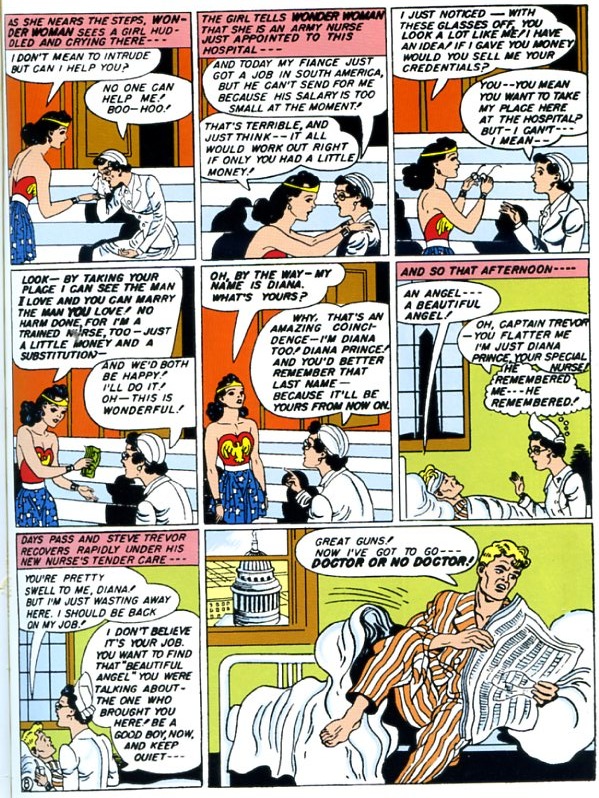

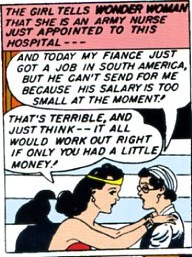

And it’s an act, moreoever, undertaken to pander to the needs of her man, as we see in Sensation Comics #1.

That’s a deeply odd sequence. Wonder Woman trades places with a nurse who looks exactly like her and has the same name. Moreover, the nurse has the same problem; she needs to find a way to get to the man she loves. The two switch places, but they’re able to do it only because they were already in each other’s places to begin with.

So a couple of points about this.

— In my first essay about WW and superdickery I speculated on the place that female/female relationships had in enforcing femininity. That is, male/male relationships (between, say, Spiderman and Uncle Ben) are often part of Oedipal drama; they’re a spur to becoming more manly, as well as a taunt for not being manly enough.

Female/female relationships, though, often seem much less fraught. In some circumstances — as with the Amazons — sisterhood can be an alternative to, or a challenge to patriarchy. But female bonds can also enforce femininity, and reinforce (subordinate?) relationships with men.

This is basically the argument of Sharon Marcus in her book Between Women. Marcus claims that close, even eroticized friendships between women were seen as an essential part of being a women in the Victorian period. Thus, close female friendships didn’t make women homosexual — it made them more heterosexual.

Marston was significantly more aware of lesbian possibilities than many Victorians were; he had a long-standing polyamorous relationship with two bisexual women. Still, I think Marcus’ analysis perhaps makes it clear why we need this bizarre scene of doubling before WW can have her sort-of-tryst with Steve. Just as male/male relationships for theorist Eve Sedgwick enforce the agonized Oedipal doubling, so female/female relationships for Marston create a stable, domesticated femininity. WW needs Diana to teach her how to be a woman.

— I’ve sort of made this point already, but…the scenario here is not, at first glance, an especially empowering vision. Marston seems to be going out of his way to disempower his heroine from the get-go. Moreover, he’s disempowering her in the name of servitude to men! WW casts off her superpowers so she can wait on Steve hand and foot. As I noted in the first part of the essay, male superheroes are constantly striving and failing to be powerful (men). The feminine, though, doesn’t need to strive; it can just be. And that’s what happens here. WW chucks her goddessness so she can go change her guy’s bedpans. Not much of a feminist message.

________________________

There are maybe other, less invidious ways to look at this though. Here’s comics critic Chris Boesel, with a different take on WW’s decision to become Diana Prince.

First the Why. Why does the god (the teacher) give herself (the eternal, the truth) to be known by the creature (the learner)? It must be for love — not by any necessity, but a free self-giving for the sake of the possibility of the relation itself. And love has a twofold dimension here. It is not only the god’slove for the creature that the god… [gives herself]; it is also for the sake of love, so that the creature might love the god, that the god and the creature might be joined in a relation of “love’s understanding.”

Okay, that’s my little joke. Boesel isn’t a comics critic; he’s a theologian. And despite the serendipitous use of the female pronouns there, he’s not talking about Wonder Woman. He’s talking about Kierkegaard’s ideas about the incarnation of Christ.

The essay is called “The Apophasis of Divine Freedom,” and it appears in a volume edited by Chris Boesel and Catherine Keller called Apophatic Bodies. For those, like me, not familiar with the terminology, apophatic theology means negative theology — the practice of describing God by talking about what he (or she, or ze) is not.

I’m going to quote a little more from Boesel, since it seems apropos to WW’s decision to shuck off her goddesshood for love. Again, Boesel is paraphrasing and sometimes quoting Kierkegaard here.

Second, the How. How is the god to create the “equality,” or “unity,” necessary in order to “make himself understood” without “destroy[ing] that which is different,” that is, the creature as creature? How does the god give herself to be known by the creature in and for love without obliterating the beloved?

Climacus [that’s Kierkegaard’s pen-name] rejects both the possibility of an “ascent,” an exaltation of the beloved creature to the heights of heaven…and of a divine “appearing” in overpowering, sacred splendor,” on the grounds that they would violate the integrity of the creature’s existence, as creature.

The “unity” of “love’s understanding,” then, must be “attempted by a descent.” And a descent, by the god, to the level of “the lowliest” of all…. Therefore, “in love [the god] wants to be the equal of the most lowly of the lowly,” and so comes to the creature “in the form of the servant.” This “form,” however, “is not something put on like the king’s plebian cloak, which just by flapping open would betray the king…but is [the god’s] true form.” The god does not deceive, but in the “omnipotence of love,” remains truly god while fully embodied as a particular human creature, just like any other human, even the lowliest of the low.

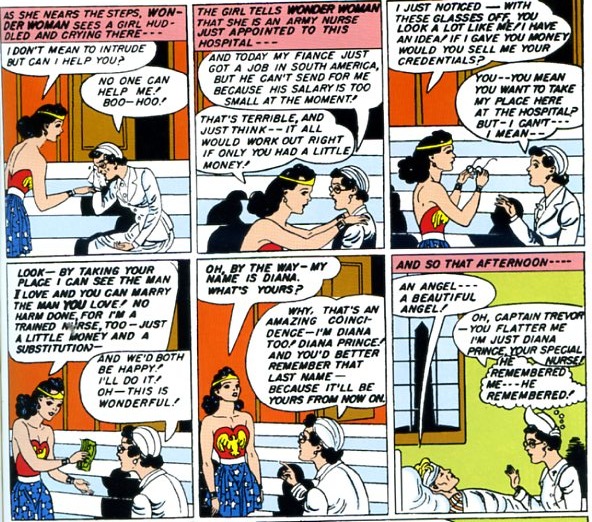

The whole analysis by Boesell/Kierkegaard fits WW almost perfectly. As a goddess, WW can’t appear to (be apprehended by?) Steve. For him to love her, and for her to love him, she has to descend and become, not just human, but a servant. She even takes over the form of a “real” human being; her double, both her and not her. The moment when Steve knows her and doesn’t know her:

is emblematic; when she is Diana (which is her real name and also her alias) Steve can recognize and love her. The angel cannot be loved as an angel, but only as a servant. From this perspective, you might argue that gender is irrelevant or secondary. Marston’s not telling a story about what women should be, or how they need to be weak and servile to attract a man. Instead he’s telling a story about the encounter with the divine, and the paradoxical manner in which one, of whatever gender, can only love the transcendent through the particular.

The thing is, though, Marston is obsessed with gender…and especially, one could argue, with the relationship between gender and Godhead. The particular divinity WW is, the transcendence she represents, is female.

Moreover, the embodiment of that transcendence is female as well. Obviously, WW and Diana are both women. But the particular formal representation of that embodiment in the comic is also, I think, coded female. I’m thinking specifically of this passage from Irigary’s essay “The Sex That Is Not One.”

Woman “touches herself” all the time, and moreover no one can forbid her to do so, for her genitals are formed of two lips in continuous contact. Thus, within herself, she is already two — but not divisible into one(s) — that caress each other.

Also this:

Whence the mystery that woman represents in a culture claiming to count everything, to number everything by units, to inventory everything as individualities. She is neither one nor two. rigorously speaking, she cannot be identified either as one person or as two. She resists all adequate definition. Further, she has no ‘proper’ name.

Following Irigary’s formulation, when WW moves from transcendence to immanence, when she becomes embodied she does not merely split — she is not bifurcated within herself into two agonized and irreconcilable halves. Instead, she becomes two who remain one — neither one nor two.

The comic form itself literally embodies the indeterminacy. Comics are built around repetition of the same figure; on a given page, Peter will draw WW over and over again. The panel borders separate these images; each is each, identity in its place. But when WW needs to cast off her transcendence, the panel borders collapse, and suddenly two images of her occupy the same delimited space.

Once they are embodied together, Diana and Diana can touch — a self-caressing which opens the way for love — and not only of one another (or of one as another). Marcus noted that affection between women was seen as aiding, not hindering, love between men and women; similarly, Irigary sees women’s duality as opening into multiplicity.

So woman does not have a sex organ? She has at least two of them, but they are not identifiable as ones. Indeed, she has many more. Her sexuality, always at least double, goes even further: it is plural….woman has sex organs more or less everywhere.

Again, the sequence here embodies the movement from two to many. The duality of Diana and Diana is multiplied on one page as they talk from panel to panel, so that we see, not just the one Diana that is two, but doubled Diana’s multiplying profligately. And then, inevitably, in the sixth panel, the one Diana replaces the other Diana while the other Diana is replaced in the frame by Steve.

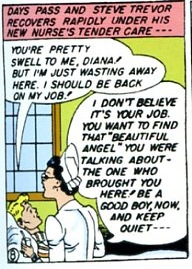

A female self-caressing self opening to love for another; that’s a metaphor for motherhood. And indeed, Diana, incarnated as a nurse, treats Steve with matriarchal affection.

“Be a good boy now and keep quiet.” Diana’s love of Steve isn’t (just) romantic love, and isn’t (just) divine love — it’s the love of a mother for a child.

Paradise Island is a matriarchal heaven, and if WW is a Christ figure — and I think she is — then she remains a female Christ figure. And what’s perhaps most interesting about that is how easily it fits into Boesel/Kierkegaard’s formulation. WW does not need to overawe Steve with her transcendent power, challenging him to become a superdick like her. Instead, she lowers herself to him, showing her transcendent power through the servitude of love. The transcendent matriarch becomes human precisely to change bedpans. That’s what divine love is. That’s the point.

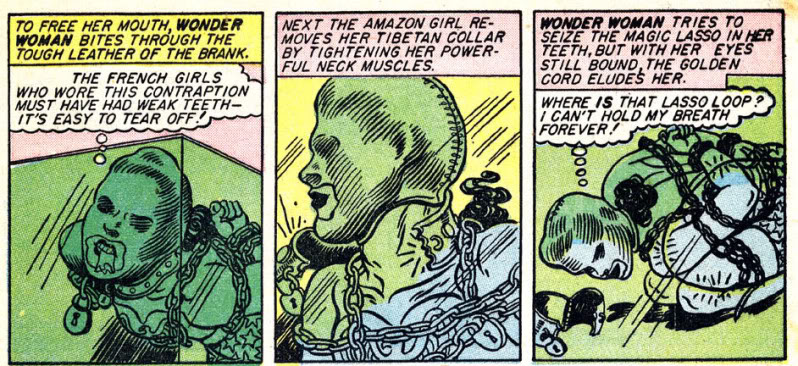

In this context, too, Marston’s obsession with loving submission, his conviction that women are superior to men because they know how to submit, and his determination to show WW’s power by tying her up, starts to make more sense.

Submission is godlike, especially submission to Marston’s ultimate authority, Aphrodite, the god of love. Because, as Christ and Nietzsche and lots of superheroes agree, the alternative to worshipping love is worshipping power. Marston’s WW isn’t a bifurcated, tormented child striving for an unattainable transcendent Oedipal Uberfatherness. She is bifurcated, but the way Christ is bifurcated, between human and divine, or the way a mother is split between herself and the child that comes from her. Wonder Woman’s not a superdick, but the super sex-which-is-not-one, which opens like a wound, giving birth to love. She sets aside her power to become a servant of that love, and, as they say in the comics…to save us all!