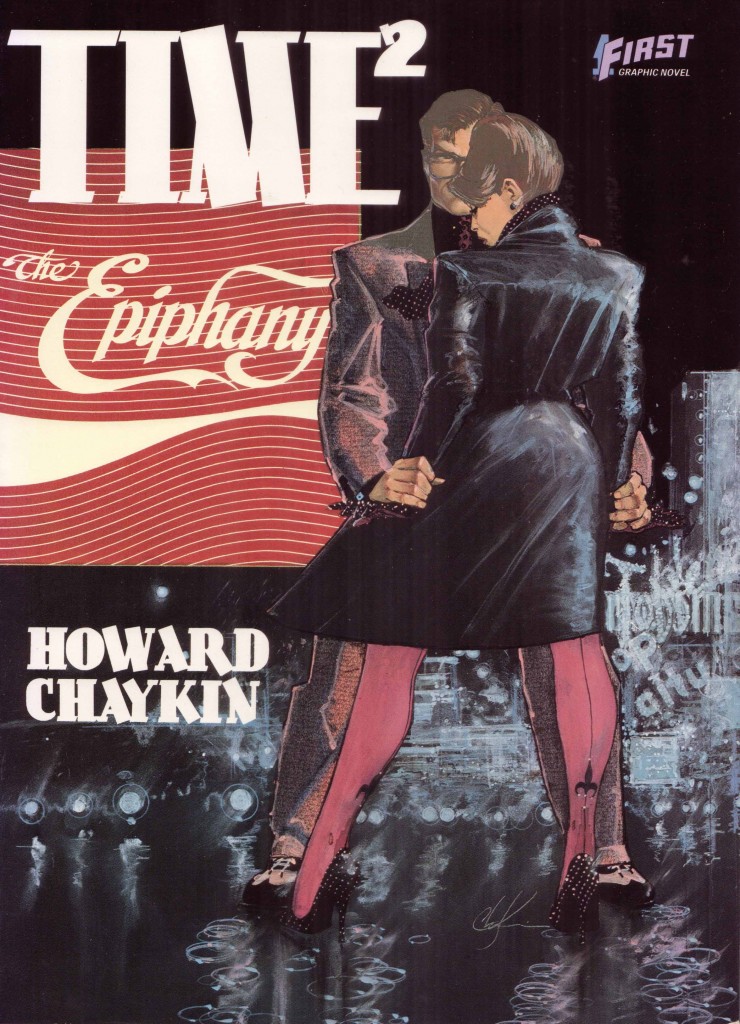

“Time² was an opportunity for me to do a magic realist-fantasy fiction version of my life. The three guys—Max, Azriel, and Dani—are idealized versions of me and my brothers, and Rose is my mother. It was an absolute hoot. I loved doing Time². It’s my most personal work, my favorite work, and of course, nobody really responded to it.”

– Howard Chaykin, Conversations

Howard Chaykin hasn’t gone back on his word. I’ve been told quite recently that he still has a fondness for that forgotten comic and holds his original art from Time² in high regard, only having recently been persuaded to part with the bulk of it. The pricing on those sheets of paper has barely managed to keep up with the rate of inflation. They were selling for little more than $100-150 (if memory serves) around the turn of the millennium and are now available at 200 Euros each (about $260), this pricing having little to do with their actual saleability or desirability (Chaykin’s early American Flagg! art is in greater demand among collectors).

Part of this has to do with the simple fact that the comic in question was one of Chaykin’s least popular, never managing to gain the critical acclaim of his work on American Flagg! or the notoriety (and multiple printings) of Black Kiss. It was allowed to fall out of print as soon as possible, the thin tomes with their horrendous glue binding gathering dust in innumerable back issue clearance bins ever since.

Yet it remains an impressive example of design and the use of narrative confusion—a technique which Chaykin perfected in the pages of American Flagg!—a magnificent synthesis of the planning and drawing of Howard Chaykin, the lettering of Ken Bruzenak, and the painted art of Steve Oliff. This is easily one of the high points of this collaborative team.

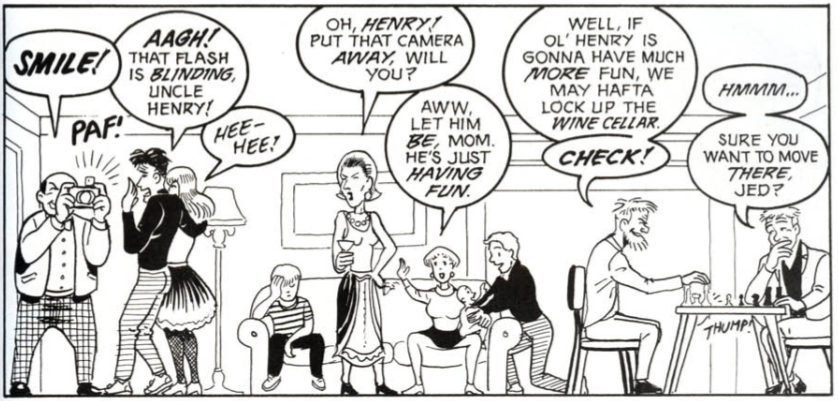

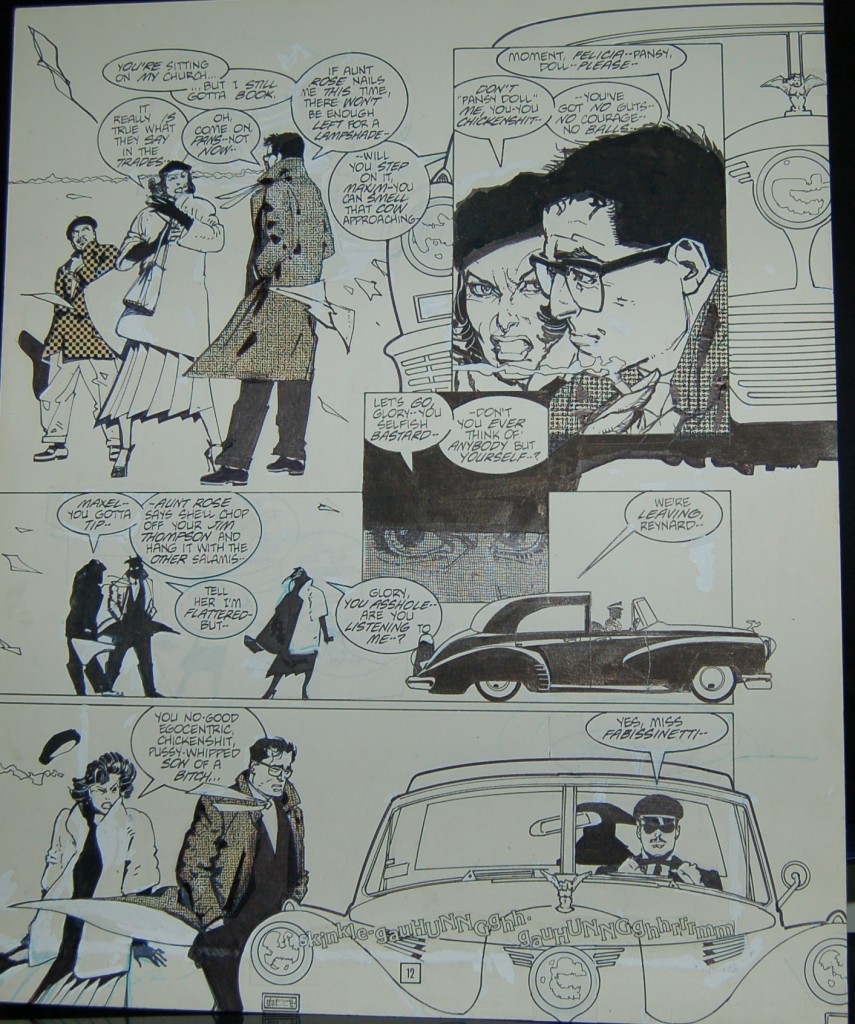

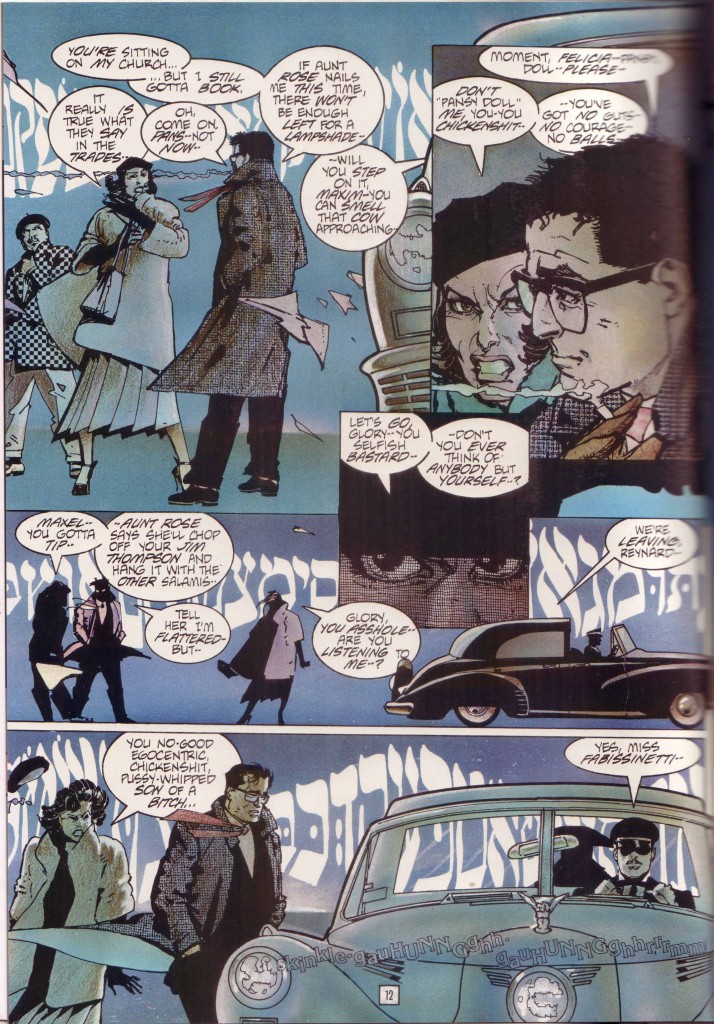

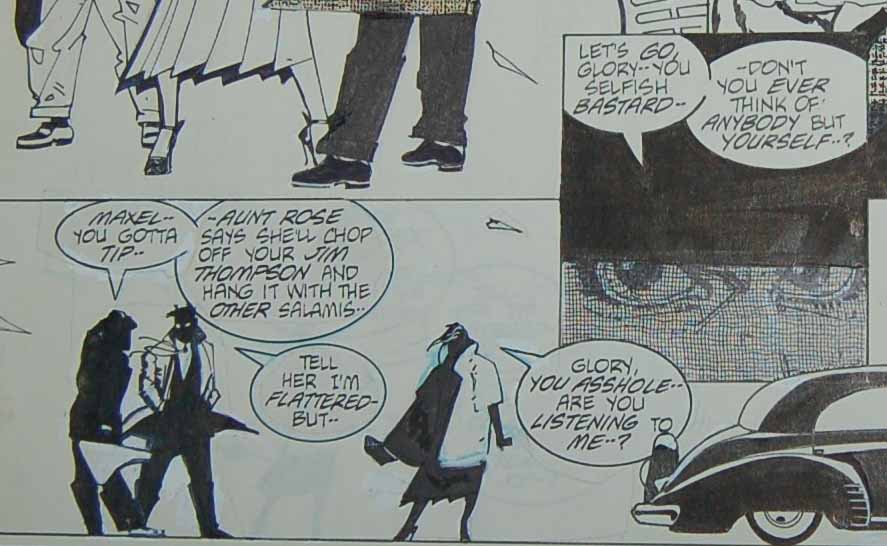

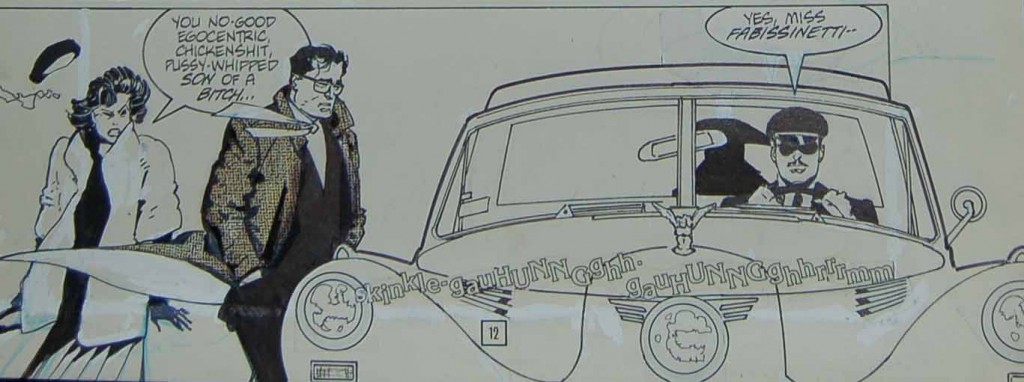

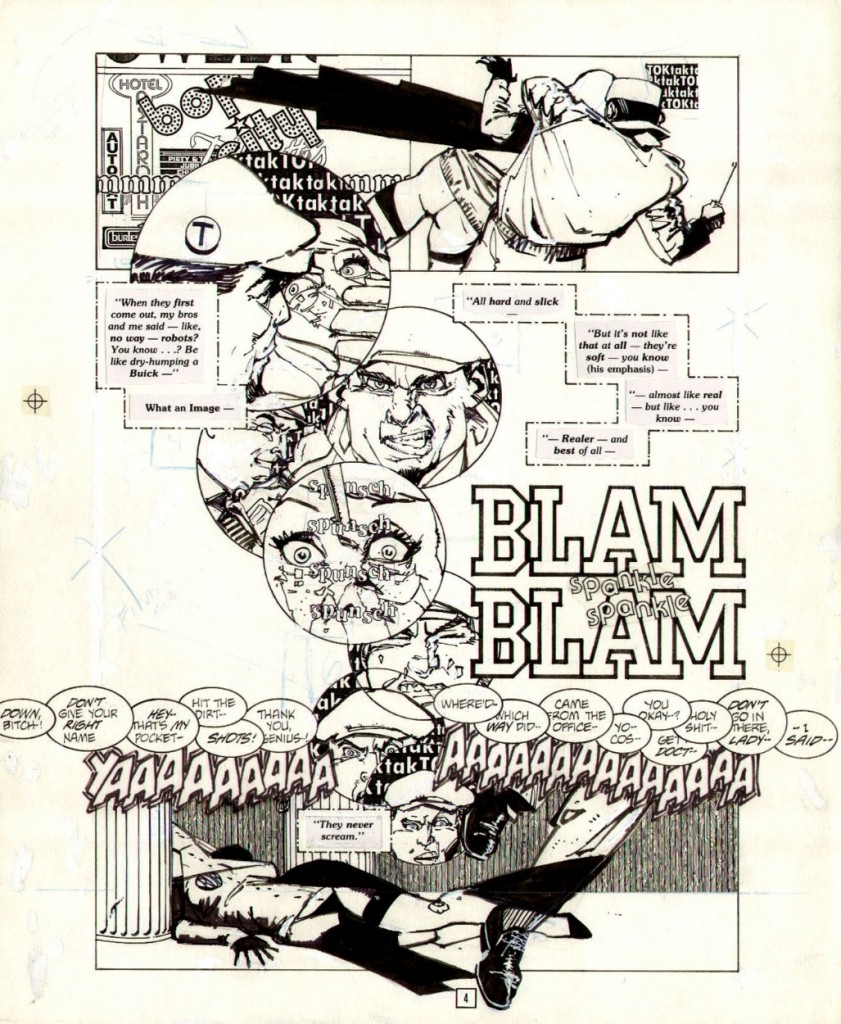

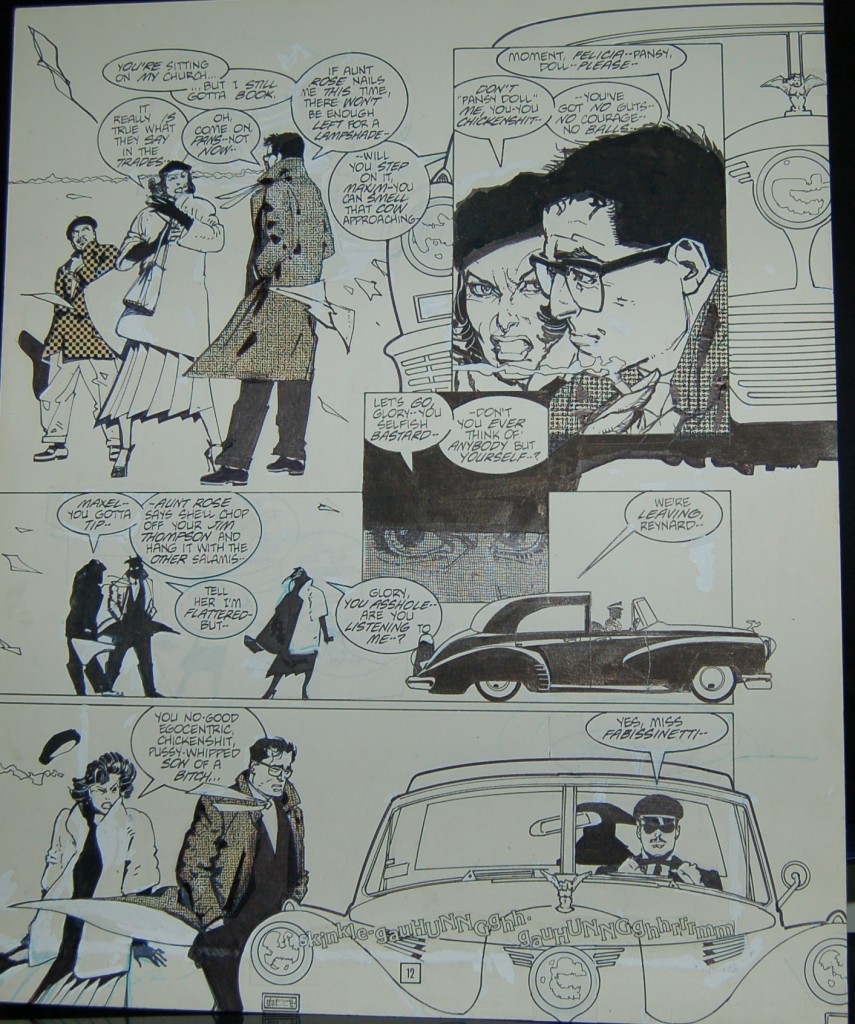

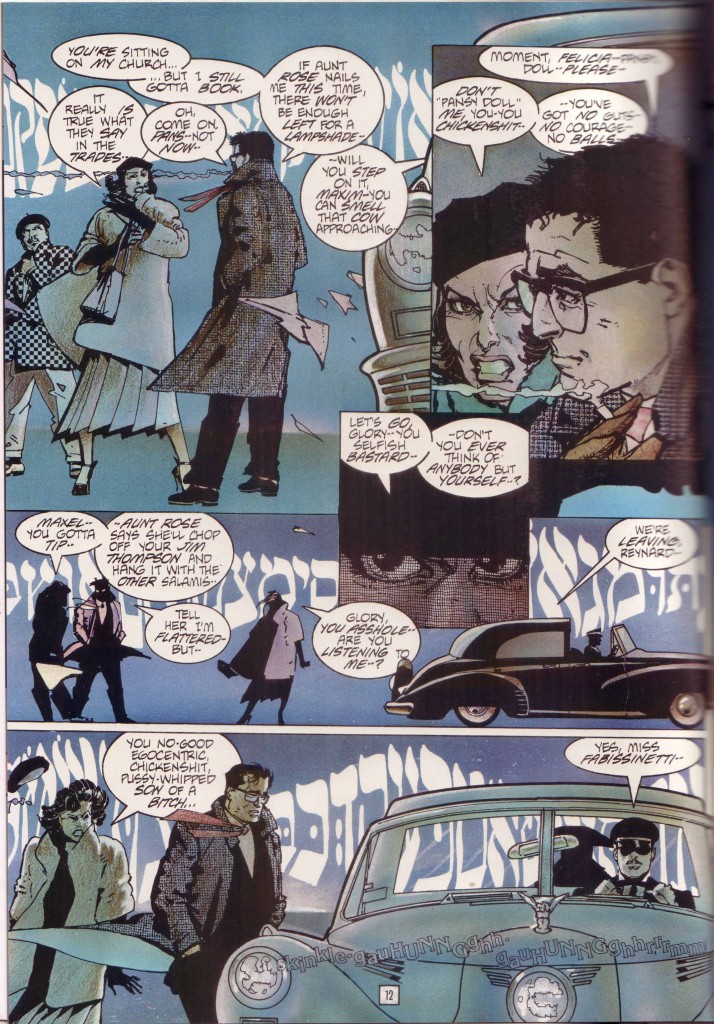

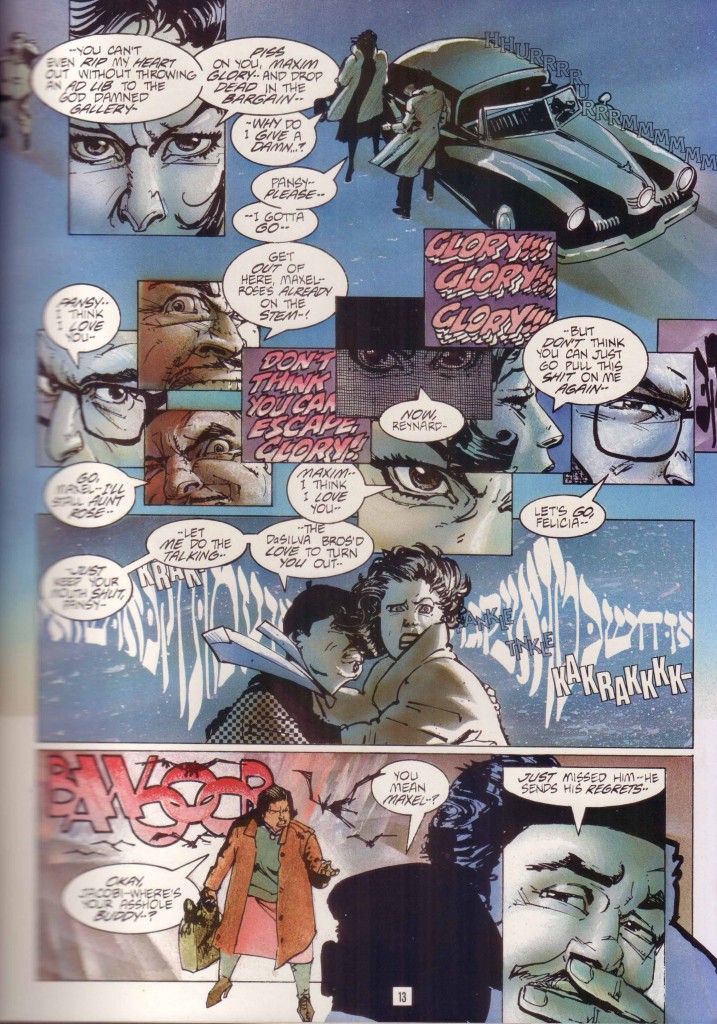

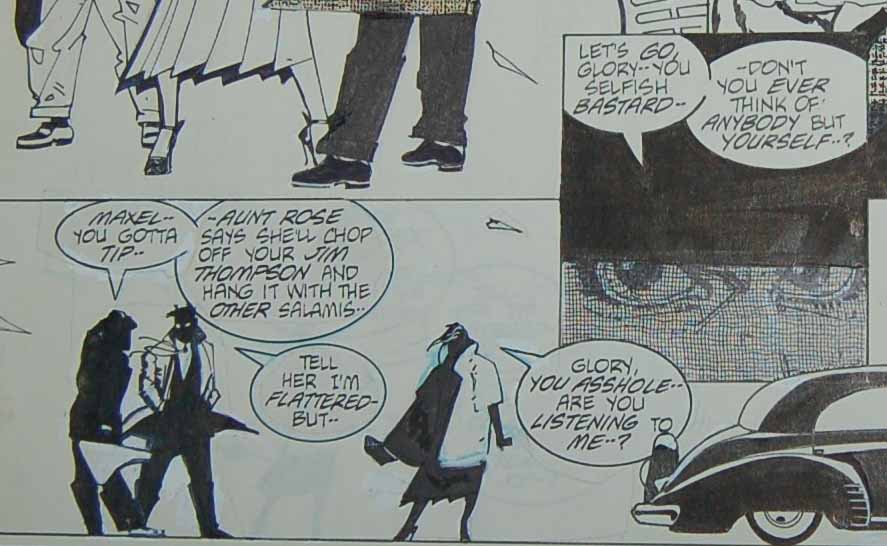

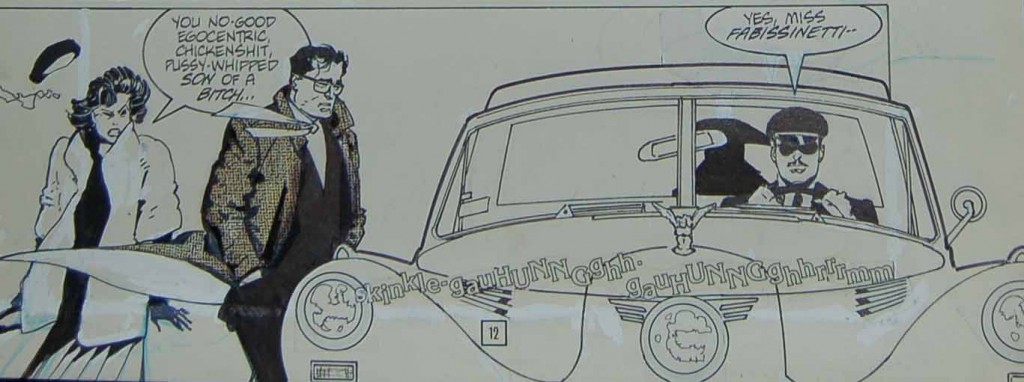

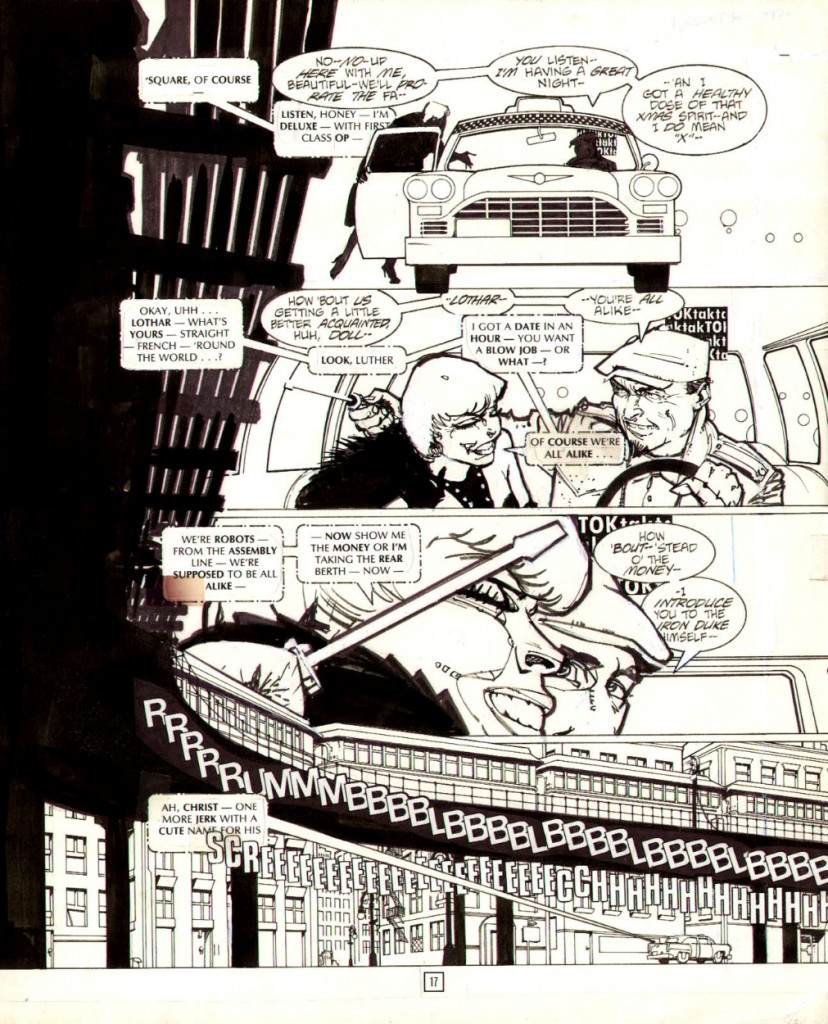

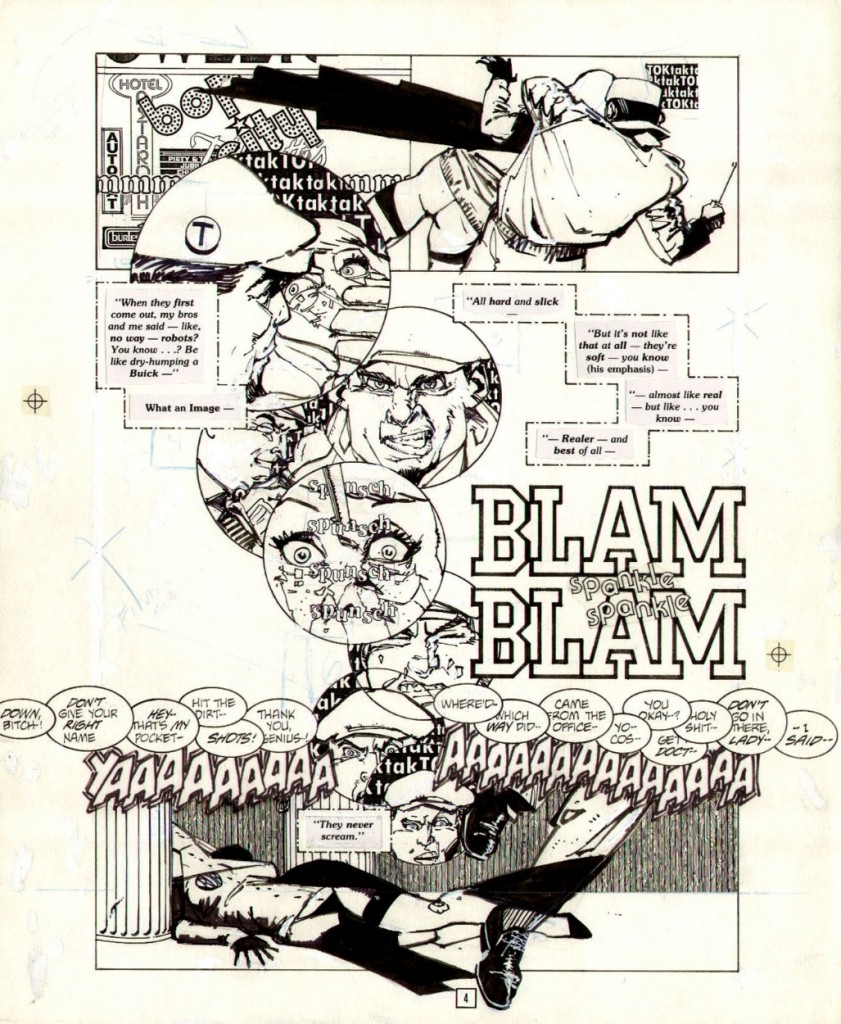

The original art itself is larger than your average modern day superhero board though not quite twice-up, bare and carrying with it all of the scars of production, as good an example as any of how the physical comic book is the final aesthetic object. The rest belongs to nostalgia, history, and scholarship. Consider page 12 (above) and its battlefield of whiteout marks, repositionings, and white spaces. The blue background denoting memory is confined to the bluelines created by Oliff as is the horizon line in the distance. The Yiddish radio transmission (or primal scream?) cutting through that space, unifying the facing pages, and signalling the imminent arrival of a crazed delicatessen owner is nowhere to be found.

This big mysterious flashback in which we see the protagonist (Maxim Glory) acting out his lines for the first time is now strangely quiet—strangled faces on aging paper. Much of Time² was built on the concept of double page spreads and this one will never tell its tale (or part of its tale) without its partner.

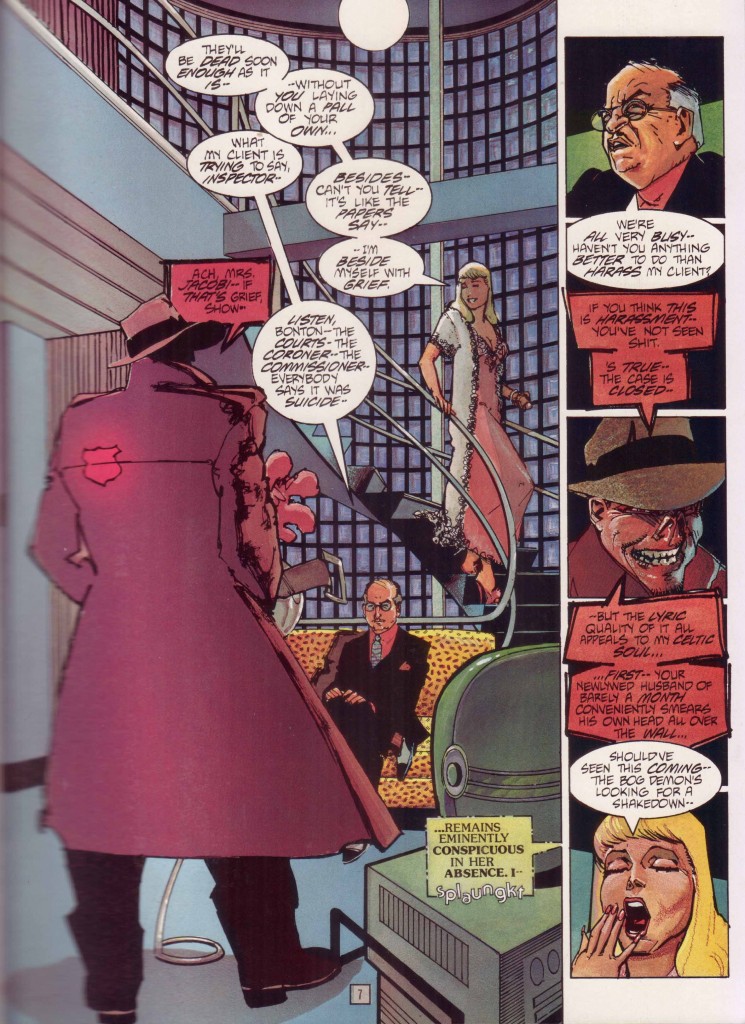

The correction marks and whiteout (that comics pentimento) suggest minor inking errors and space made for that Chaykin specialty—overflowing word balloons. Chaykin was never one to care about crushing a page with text and his words are cramped into a number of tight corners by Bruzenak. If anything it transforms from hurdle, to design element and hence to feature, like the controlled improvisations of a jazz artist.

In the second panel of page 12 we see the female figure moved to the right to make space for this dialogue, her words now protruding into the hatched lines of the center panel inset meant to denote a shadowy countenance and a veil of anger; the words “bastard” and “asshole” now inserting themselves into the schema as a central theme as it were.

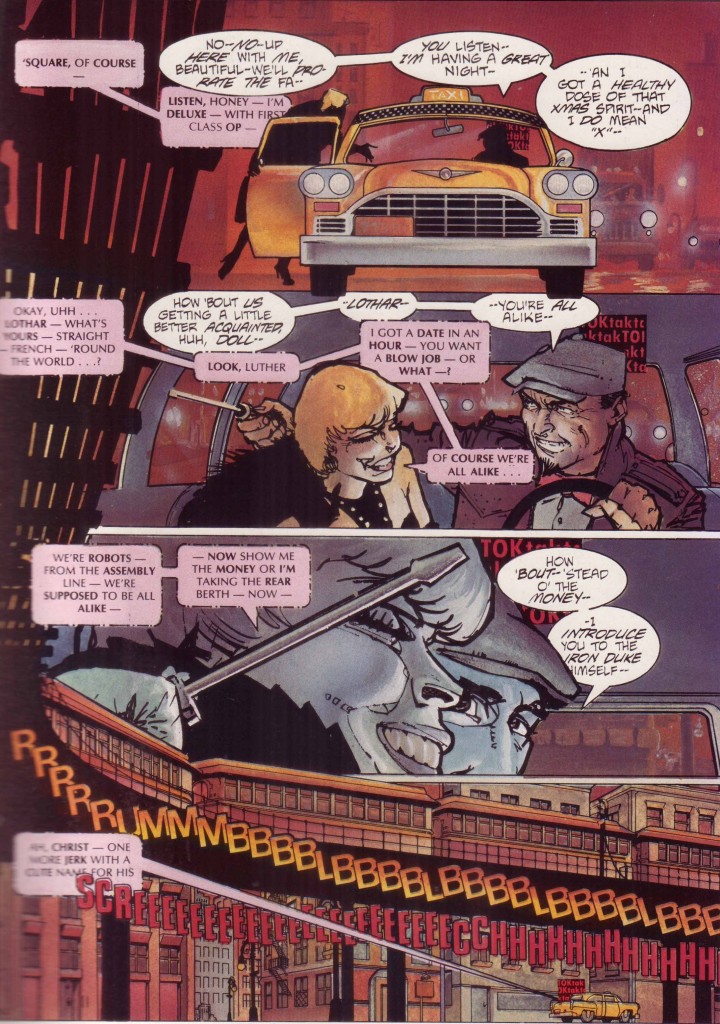

So too the interaction between the silhouette in the back of the chromed luxury vehicle (Miss Fabissinetti) and her chauffeur, Reynard; the former’s dialogue straying into the edges of the first panel and her discourse with her driver shoved to the right border like an unwanted intrusion. All of this not making sense in the flow of dialogue, a distracting placement meant to mimic her encroachments into Maxim and Pansy’s conversation. The panel borders are removed in the bottom tier to balance the page and accentuate the prominence of the vintage automobile which dominates the entire right half of the art. Maybe Chaykin just liked drawing cars (he seems to have one on every other page), or maybe it’s a link between the robot killer and Maxim who negotiate and pepper their vehicles with acts of violence (physical and verbal) towards women.

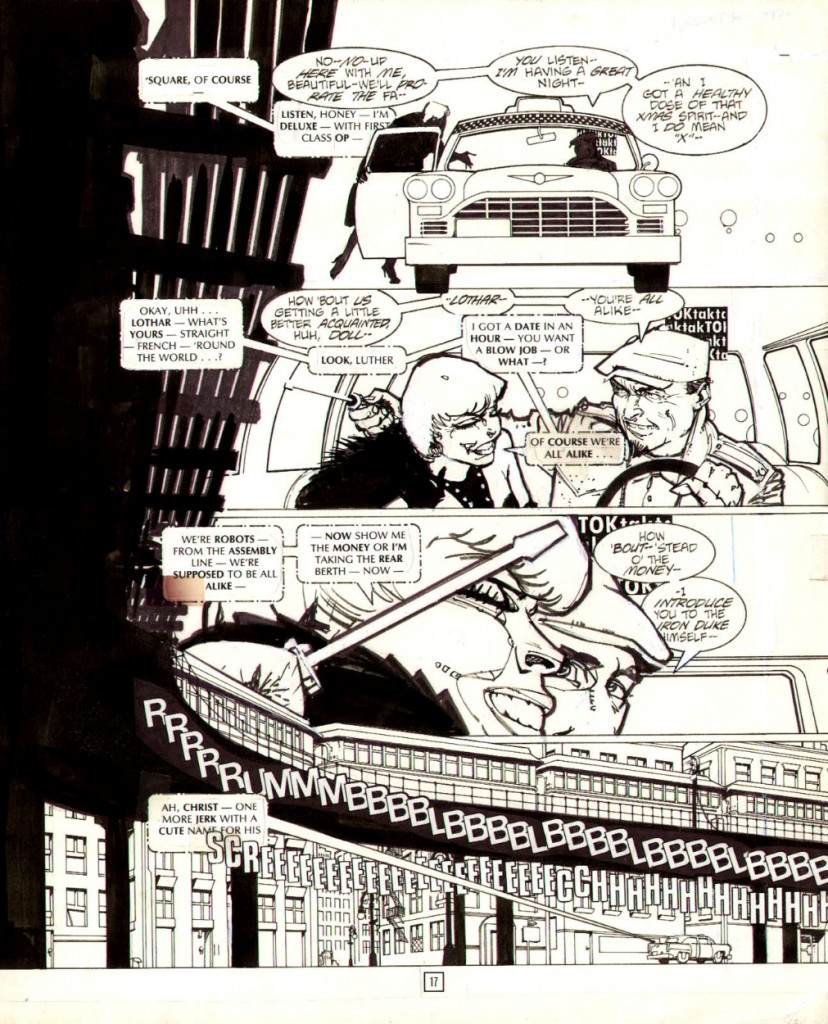

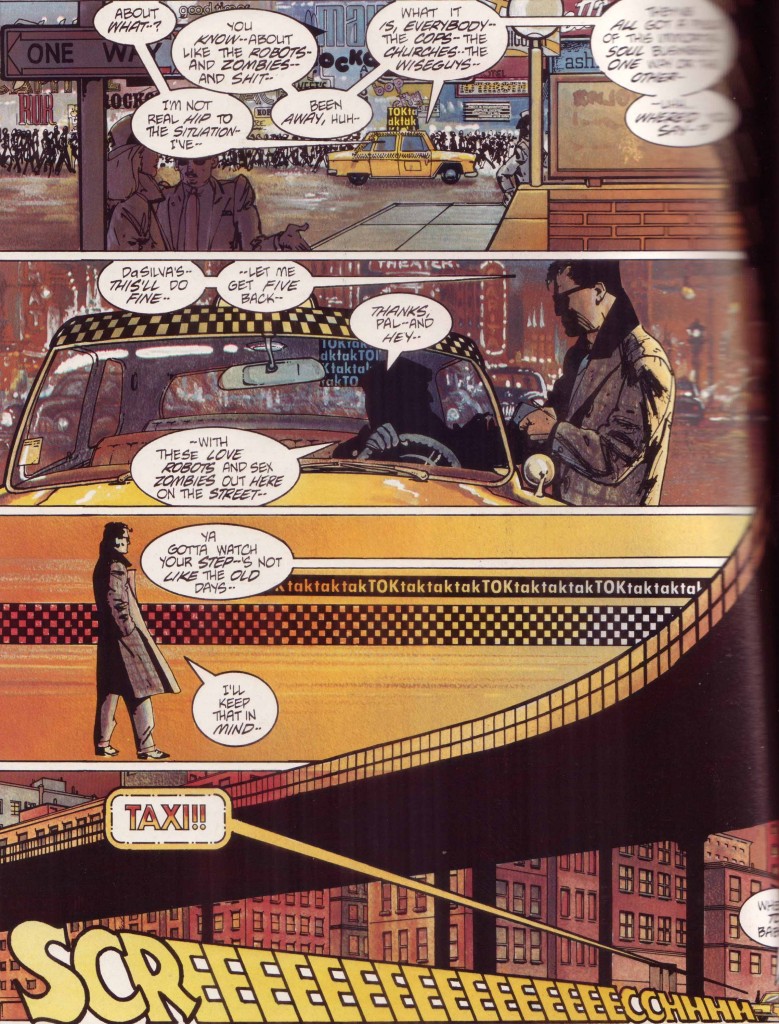

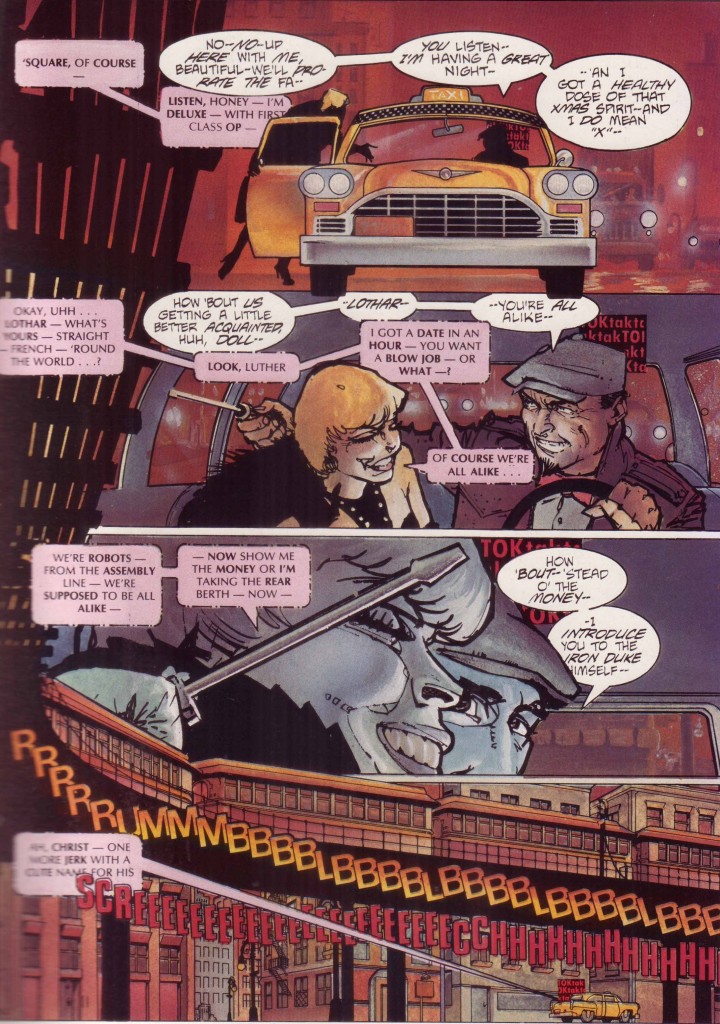

Such is the case with the double page spread on page 16 and 17, the original art for page 17 now available but orphaned from its partner.

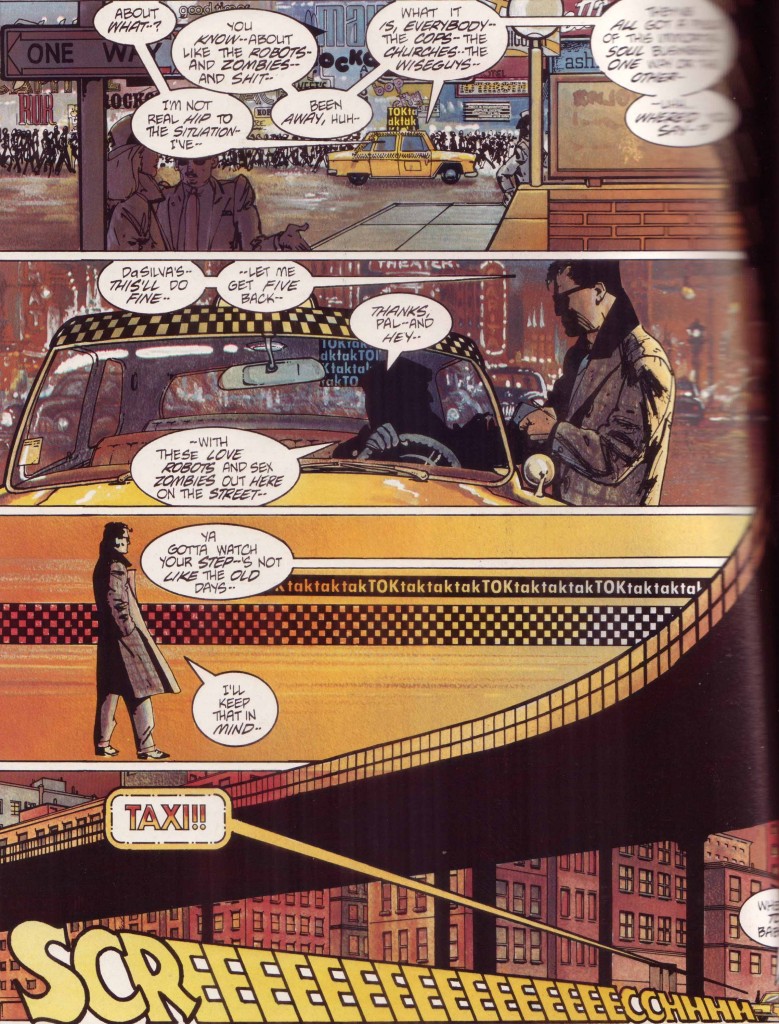

The dividing line is a rattling subway train, the multi-hued congestion and city lights once again lost to the bluelines. The yellow streak of a taxi also disappeared.

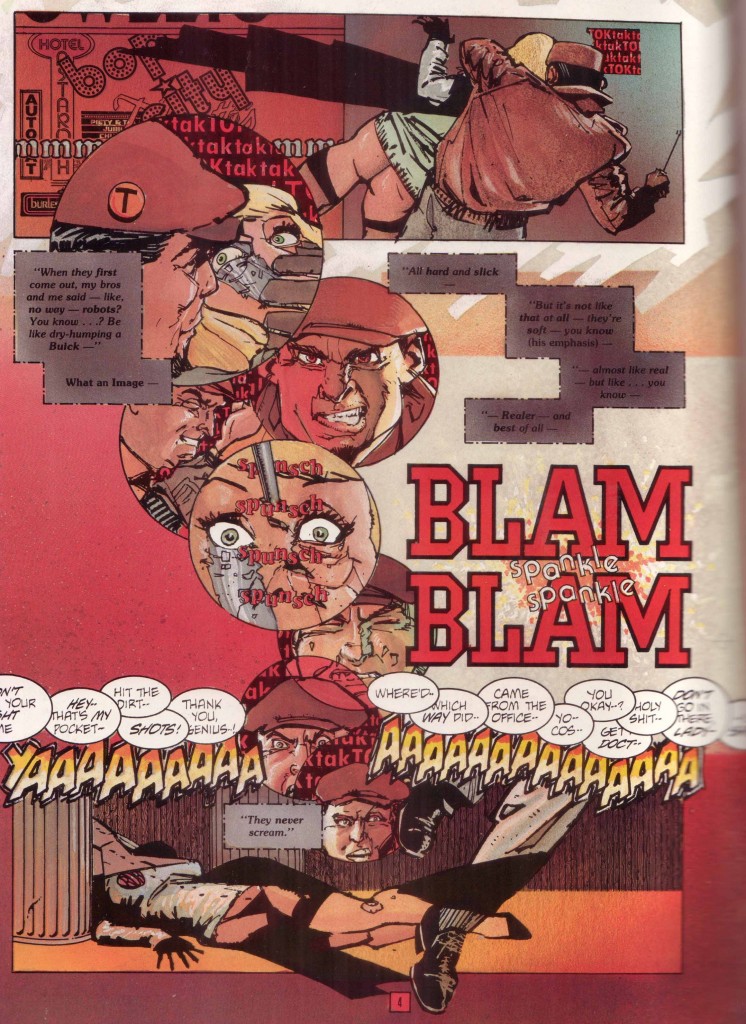

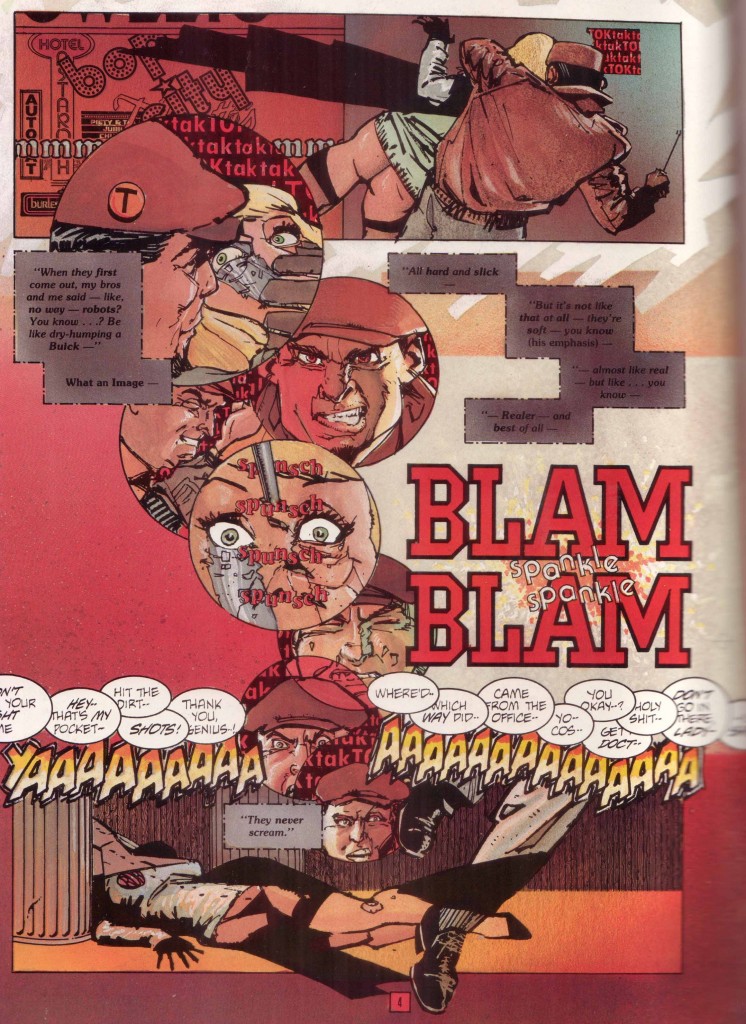

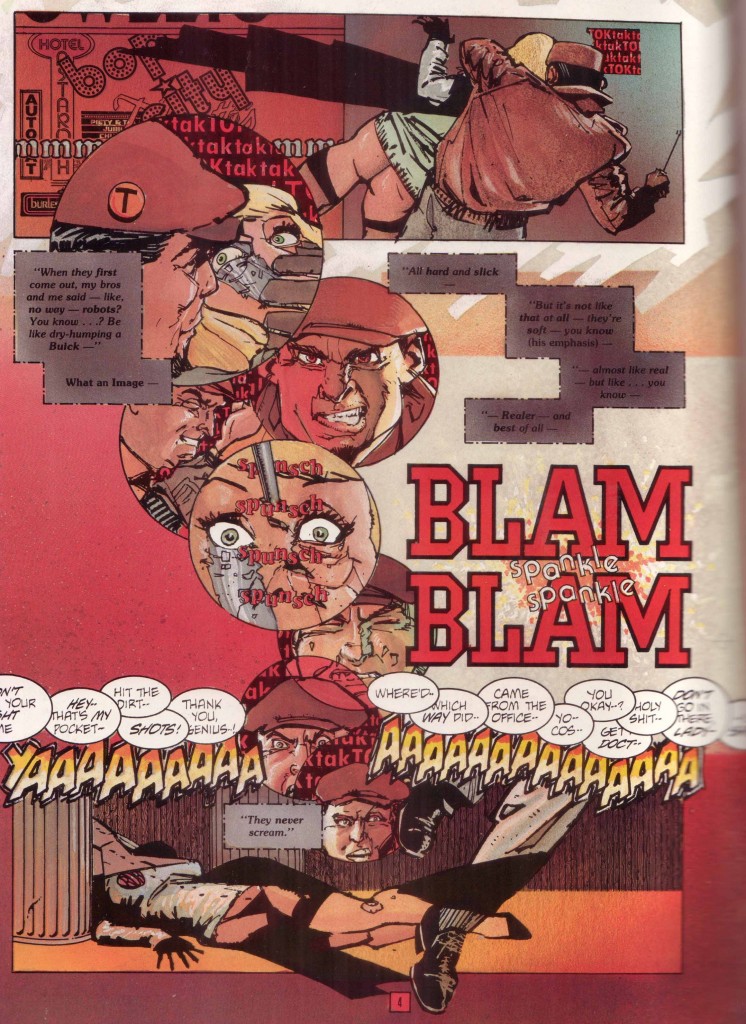

At other times, the original art reveals the joins in some of Chaykin’s bravura maneuvers. Page 4 is a smear of red neon and fury (not blood since robots don’t bleed).

Everything else comes to the fore once the parts are no longer unified by Oliff’s colors and the obscuring vision of the printing press,

The thick paste-ups of Bruzenak’s letters which seem so integrated in the comic are now seen in their rough state, the jarring changes in type (sizes, fonts, shape) a soundtrack for the city. The ink lines more clearly reveal their purpose—circular panels rising like thought balloons from the corpse at the bottom of the page, the killer’s face cracked and distorted in its final moments, the final cognitive dissonance of the android.

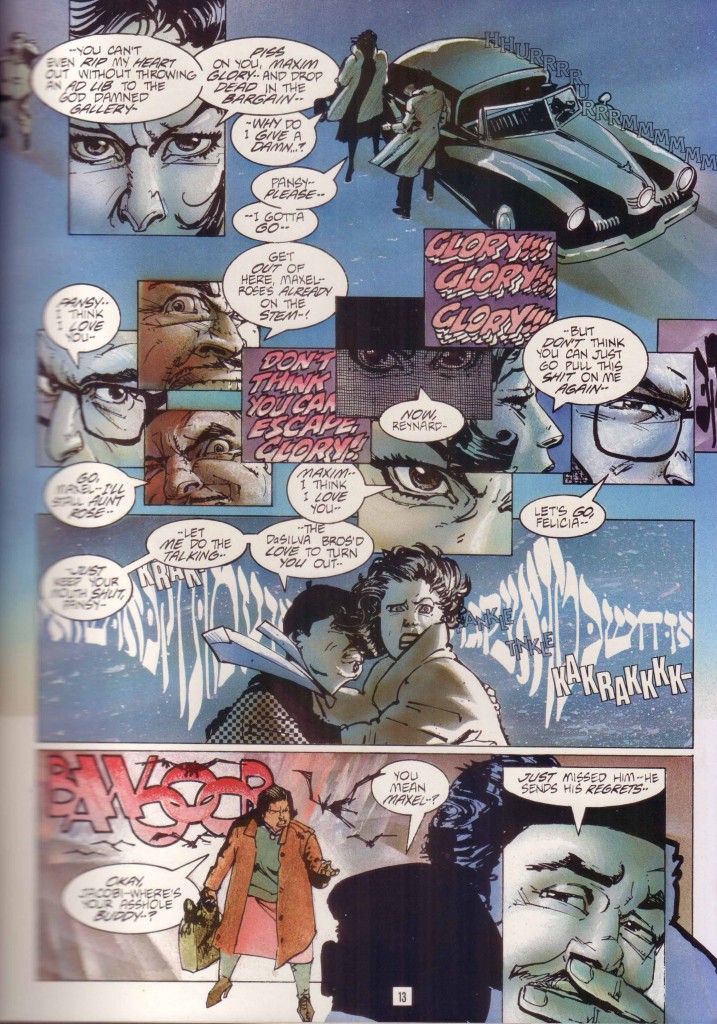

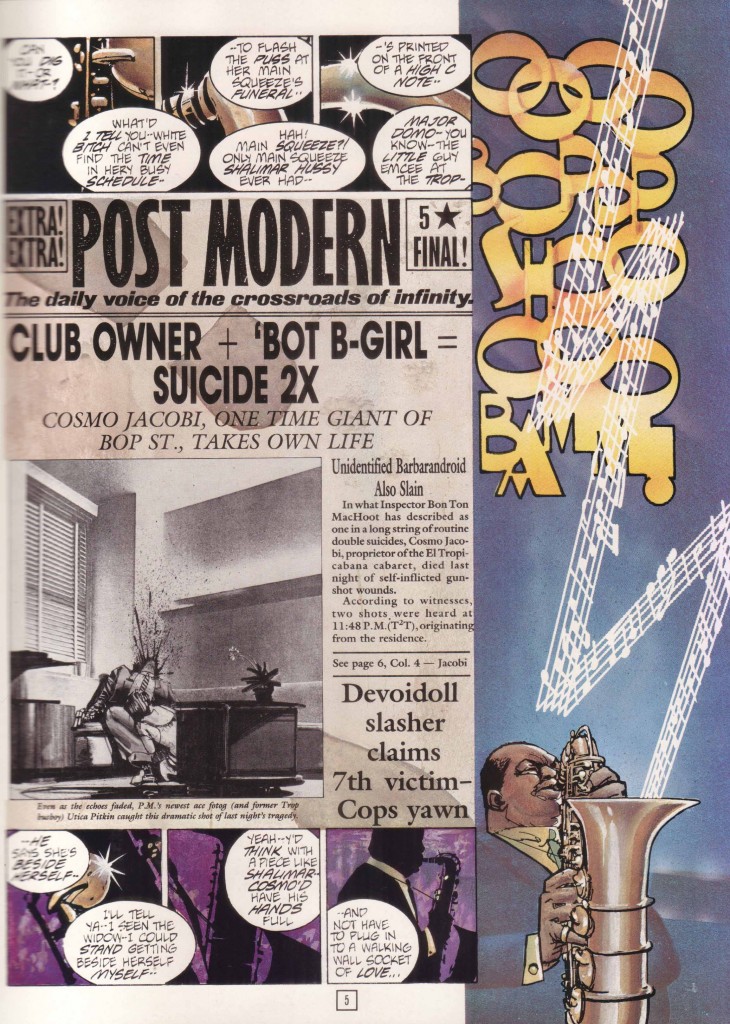

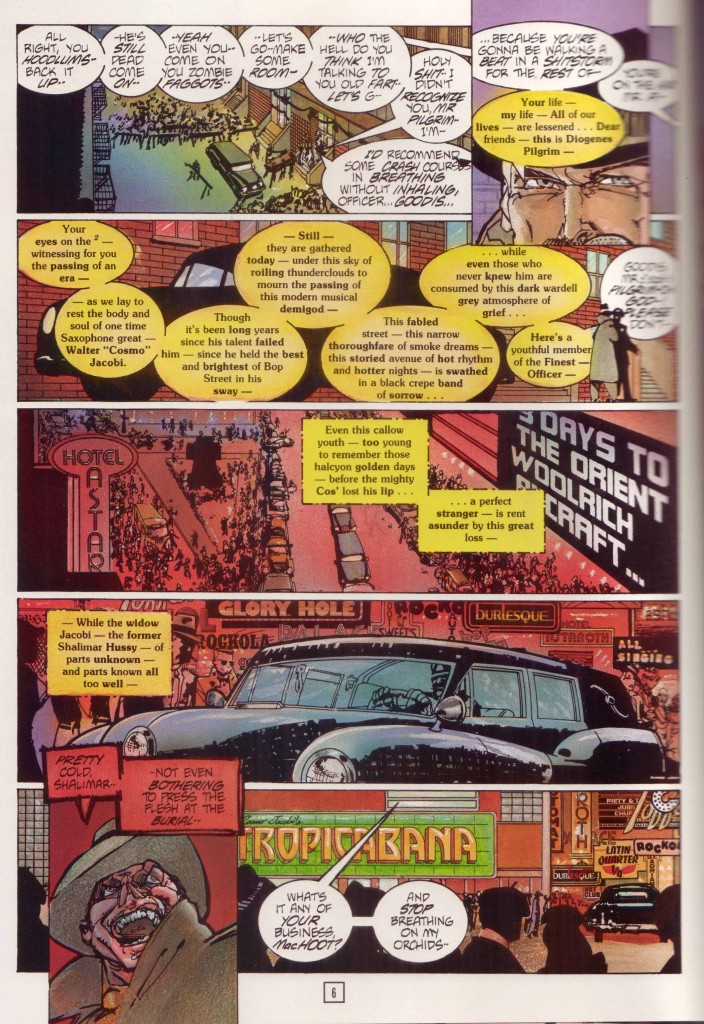

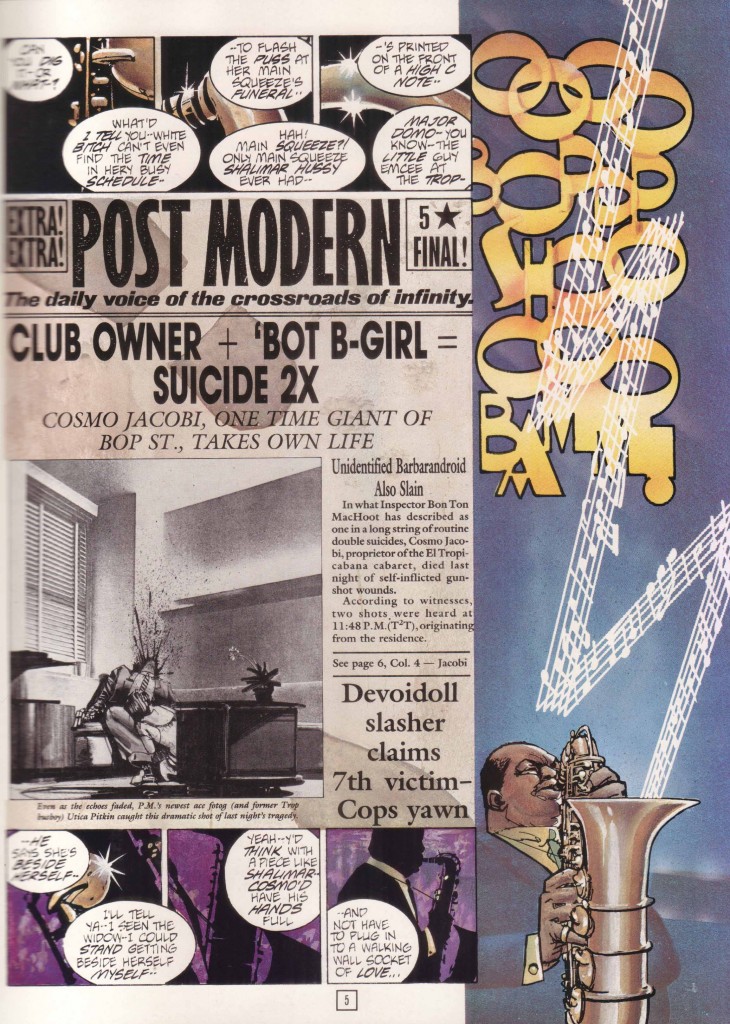

The string of disembodied dialogue sitting on the upper border of the bottom panel is a mystery to the first time reader, a cacophony floating across Time² and Chaykin’s world. That final word balloon (“-I said–“) connecting to the following page which announces the funeral and then the suicide of Cosmo Jacobi, this inverted revelation part of the Chaykin bag of tricks.

The murderer is using a screwdriver to do his work but gun shots ring out from an unknown source, for a moment overshadowing the “taktaktak” of mechanical parts and heels. A scream tears across the bottom of the page even as we’re told, “They never scream.” All of this applying to the opposite facing page: the double bang of a double suicide, the horror and morbid delight in its discovery. It is Oliff’s colors which form the dividing line between the grey marble interiors of Cosmo Jacobi’s office and the dirty red pavement of a back street killing. We might find something comparable in that confusion of sound and image seen at the start of Segio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America where Robert De Niro remembers the past through an opium haze.

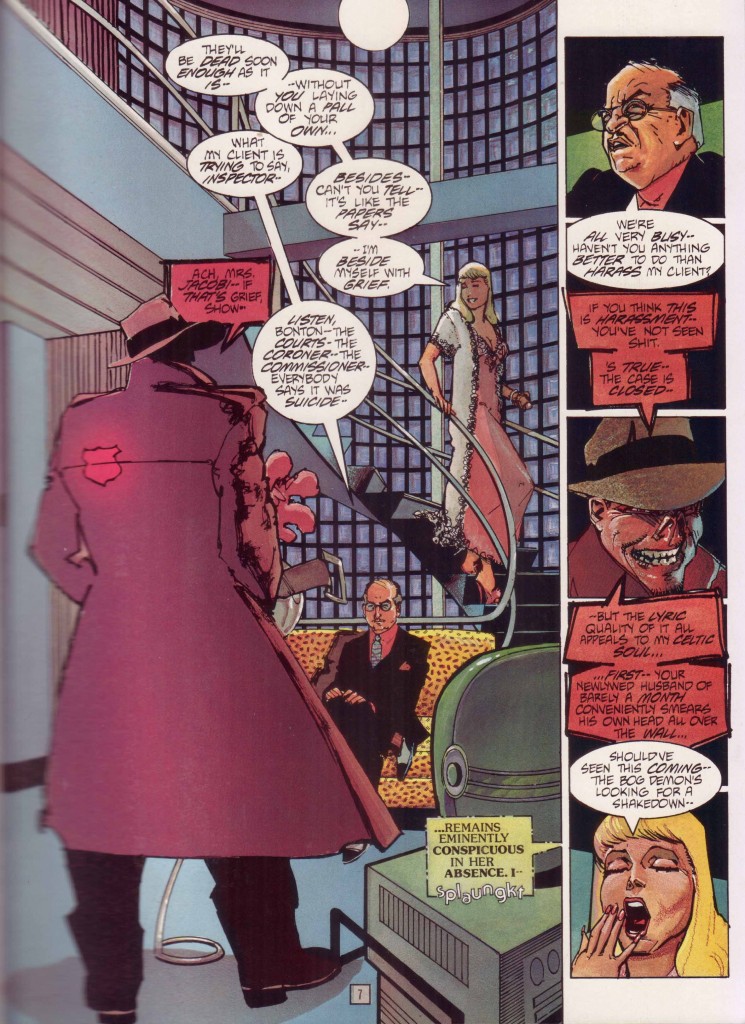

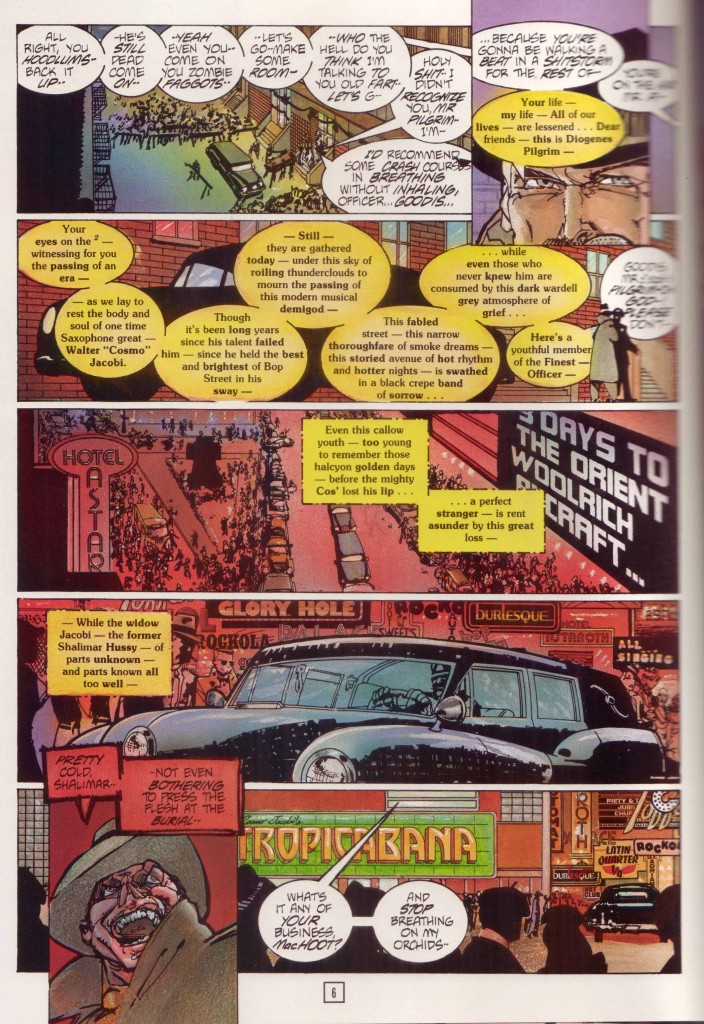

As the narrative of Cosmo’s death and the lack of despondency of his widow gathers pace, Chaykin continues to demonstrate his (over)confidence in his reader’s abilities. Page 6 begins with the neutral words of radio hack, Diogenes Pilgrim, passing through placid disconnected dialogue into anger with an unknown person, hence to a live radio transmission (colored yellow), an electronic signal (in dotted square balloons), and then the crackly end of a burbling radio in Shalimar Hussy’s apartment on the opposite page. So goes the rest of the comic, words from separate characters melding into each other as evidenced by the strangely adherent word balloons.

These are instruments singing from a score, a decadent and dissonant symphony of the city: the vanishing dialects of urban America; the genteel persistent cussing which never resorts to the word “fuck”; the elemental force of Jewish relatives; and the electric jazz cool which is (presumably) America’s greatest contribution to world culture. Chaykin states that “at its core, what Time² is, is the underworld of the city of tomorrow as visualised in the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair.” This is a world where matrons pimping demons from delicatessens are the norm, and religion and the after-life have been capitalized and released as IPOs; a lost America of the early 20th century with its bebop soundtrack, constructivist sculpture, fine dressing, and limousines with open driver compartments—a memory never never land of every time.

Jaime S. Rich links the innovations here to the work of J. H. Williams III:

“It’s a mash-up of art deco design, the seediness of old-school New York, and a cynicism about the idea of a better tomorrow. It is simultaneously nostalgic for a past Chaykin knows never was and a future that can never be….Chaykin is talking about the artistic process and living with one’s mistakes, about the clash of old-world superstition and new-world technology, about learning not to care about the stupid crap and also how to deal with relationships as an adult who actually knows a thing or two—again, heavy-duty stuff you’ve had to live through to appreciate.”

Rich sees a richer theme beneath this exercise in noise and style and I have no doubt that had Chaykin’s series reached fruition, that is exactly what we would have got. As it stands, and even with its sequel (the less satisfying The Satisfaction of Black Mariah) what we have in these 48 pages is dense prologue; a baroque joke where the punchline is totally inconsequential because its reason for being is ornamentation and counterpoint, a stream of consciousness tapped from Chaykin’s mind and life without neat ribbons or meaningful closure. As Jog puts it:

“[Time²] feels like an exercise in extended free-associative linkings of Chaykin’s internal iconography. Maybe that’s why it didn’t do all that well with readers. Proper plots do eventually emerge, more or less, but they are immediately submerged beneath the sheer import of existing in Chaykin’s universe, a pure pop surface cityscape that somehow feels achingly personal, if only through the way its creator lavishes his attention upon it.”

It is always painful when the public rejects that big personal statement and values it at rock bottom prices. A communal failing which should be seized upon gratefully by any comic art collector.

* * *

Notes from the web:

(1) Bluelines as described at Steve Oliff’s site

“…. a full color method developed in Europe, which a few American publishers used in the years just before computer coloring became the industry standard. It involves coloring on an art board that has a blue version of the line art printed on it. Then the black is shot separately, and there is an acetate overlay to show the colorist what their final product will look like. These bluelines are the actual color that was photographically reproduced. The colors are opaque watercolor (goauche), acrylic airbrush paint, colored pencil and Pantone film. They are larger than guides, and fully rendered color…”

(2) And from Frank Santoro’s inquiry into Oliff’s coloring:

“One of the main things that separates Time² from my earlier coloring jobs was that I mixed up my own special palettes of colors to airbrush, and then I used some of those same colors to paint with. Then on top of that, I was using some of the leftover frisket (a masking film) to create patterns of color. For instance there is a big shot of a girl sitting on a couch. The pattern on the fabric is mostly used frisket pieces. We used spatter and colored pencil extensively to give texture. I also used Pantone films to cast shadows over the colors once they were rendered. And finally, Howard came back in and gave a lot of the faces hard edged color. He felt some of my color edging was too soft, so he cut in some highlights.”