We’ve had a lengthy thread about the relative merits of Watchmen here. Lots of interesting contributions from Eric Berlatsky (my brother and an Alan Moore scholar); Marc-Oliver Frisch; Darryl Ayo Brathwaite (who wrote the original post); Chris Mautner, and just a ton of other people. For me personally, though, the highlight has been Jeet Heer’s negative take. As Ng Suat Tong said recently, Watchmen hasn’t attracted a lot of skeptical criticism. Anyway, I thought I’d reprint his thoughts here. (Noah B.)

Heer’s comments have been extensively rearranged and edited so that they can be read through with a minimum of difficulty. Please see the numbered links for the original comments. (Ng ST)

(1) The idea that Watchmen, of all things, is the greatest graphic novel ever is so alien to my experience of art that I find it fascinating. I’ve actually read Watchmen a couple of times to figure out why some people love it so. And while I can recognize the craft and intelligence that went into it, I’m still left with a work that lacks any of the humanity, humor, and depth to be found in the works of Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, Jaime Hernandez, [and] Gilbert Hernandez.

(2) [In] brief, the political critique of modern America to be found in Lint or The Death Ray seems to me much sharper than the politics of Watchmen. Both Lint and Andy are recognizable and plausible personality types whose character traits reflect dark aspects of the national psyche. That’s one example of many.

(3) [The] best argument that can be made on behalf of Watchmen [“is that superheroes and pulp narratives are a pretty important way in which we think about our geopolitics and our selves.” (Noah Berlatsky)]

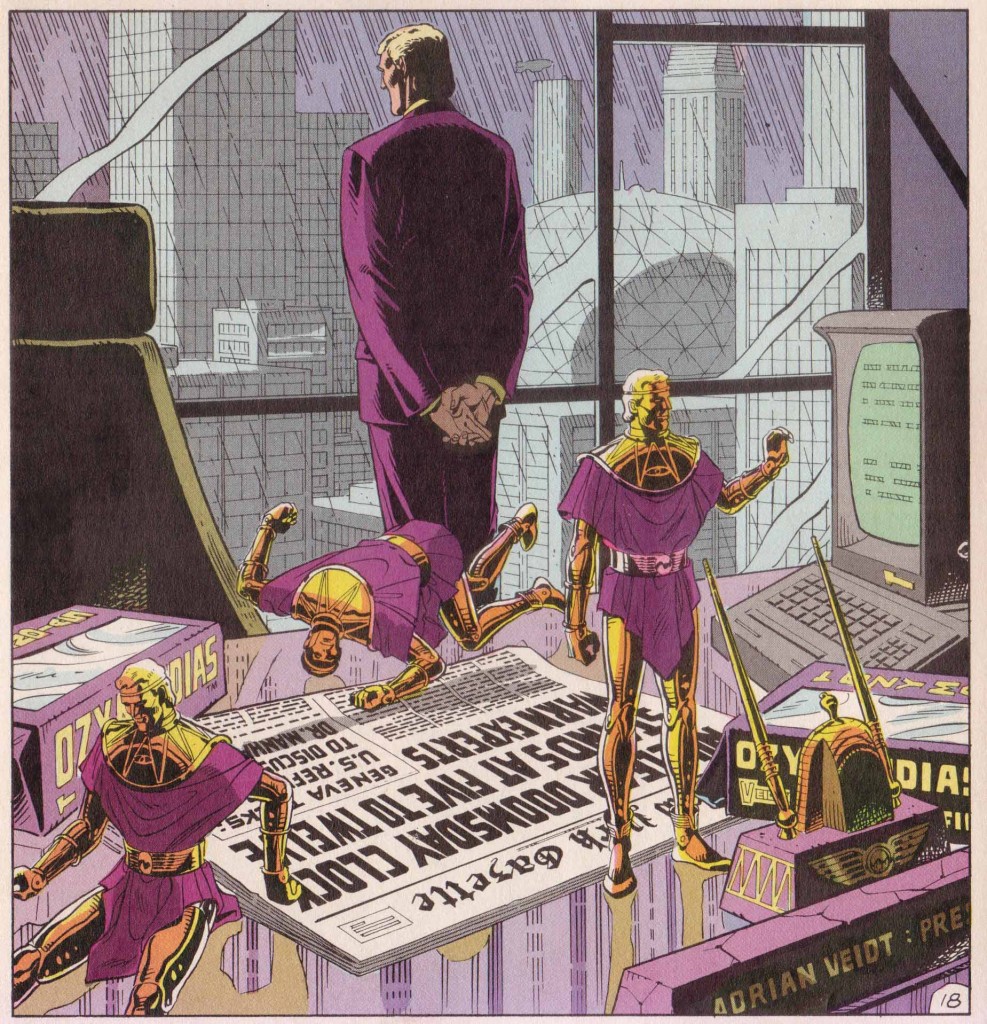

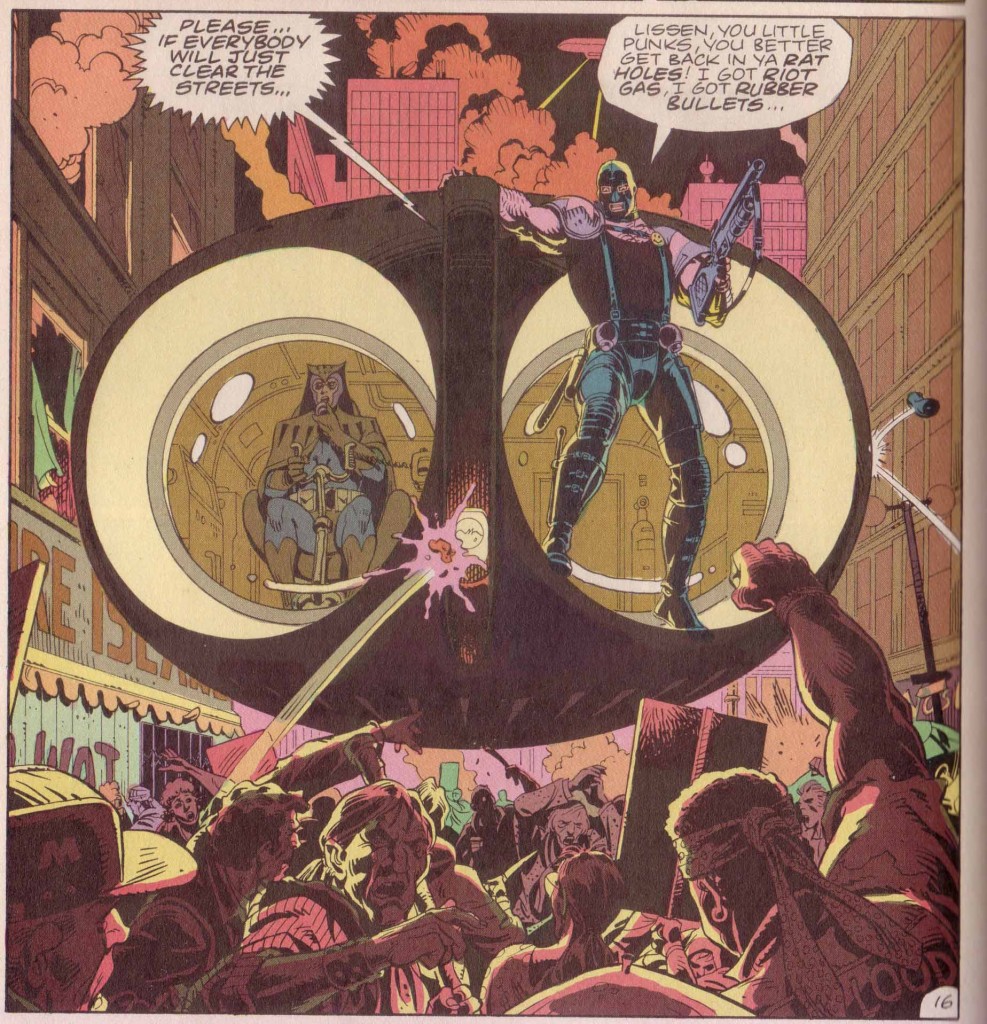

The problem is that politically the book accepts the geopolitical implications of superheroes on their own terms, so the only solution to nuclear Armageddon is the intervention of “the world’s smartest man” and the disappearance of the superhero god. For a professed anarchist, Moore has very little faith in grass-roots political activity. In the real world, the Cold War came to an end because of human agency: Gorbachev and other communists apparatchiks started to see that the regime was untenable, and were pushed for reform by dissidents while in the west Reagan had to start negotiating with the Soviets because of the peace movement. So the real heroes who saved humanity from nuclear war were figures like Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov, Lech Walesa, Gorbachev, E.P.Thompson, Helen Caldicott, etc. and the millons of ordinary people on both sides of the Iron Curtain who refused to accept the Cold War consensus. There are no counterparts to such figures in Watchmen: humanity’s fate is decided by superheroes (one of whom is willing to sacrifice millions of lives for his political agenda, another of whom is indifferent to humanity’s continued existence). There’s a despair for humanity at the heart of Watchmen which I reject both on political grounds but also because it seems callow and unearned. The darkness of Moore’s vision is ultimately closer to Lovecraft than to Kafka (think of the giant tentacled space monster Ozymandias concocts).

(4) It’s true that both the United States and post-Soviet Russia have many flaws. But fortunately there are people in both countries who are working to make things better and challenging the authorities. This type of resistance is notably absent in Watchmen. V for Vendetta is an interesting book because it does show resistance to the ruling class, but that resistance takes the form of a superhero. We can take control of our destiny but only if the superhero shows us how (and if we’re a woman, he might have to torture us along the way). There is an interesting tension between Moore’s anarchism, his philosophical determinism, and his use of the superhero genre. In my charitable moods I like to think of this tension as fruitful rather than incoherent. It certainly helps make Watchmen a little bit less programmatic than it would otherwise be.

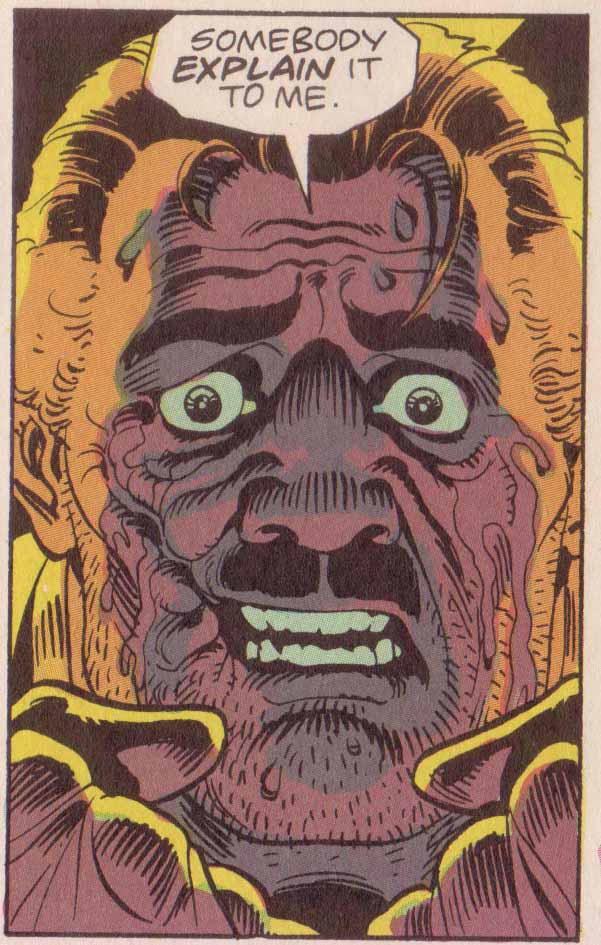

(5) [If] we take the deaths in Watchmen seriously we should regard Ozymandias as a moral monster, a veritable Eichmann. Yet even after the extent of Ozymandias’ actions are revealed, he’s treated not as a moral monster but rather as a pulp figure, a superhero-who-turns-out-to-be-supervillian. His plot is so outlandish that we can’t treat it seriously and feel the full moral import of his actions. (6) The thing is, in the context of the book Viedt is cool in the way that Rorschach is cool. Viedt has a secret hide-away, just like Superman! He’s the smartest man in the world and a gifted inventor, just like Lex Luthor! He’s always one step ahead of the game, just like the Kingpin or Dr. Doom! So as you read about his plot, Viedt doesn’t seem like Eichmann or Beria or Pol Pot. He seems like Dr. Doom or Magneto. So it’s hard to take his crime or moral culpability seriously. Or at least I can’t take it seriously. His murders don’t seem real. (By contrast, the killings in The Death Ray are chillingly believable). (7) If the squid is supposed to be idiotic and Ozymandias is an idiot and the ending a stupid anticlimax, then doesn’t that undercut the moral horror we should properly feel at the fact that within the narrative Ozymandias has killed millions of people in cold blood? We don’t think of Eichmann as an idiot who came up with an idiotic and anticlimactic scheme.

(8) It seems to me that Eric, Noah, and Mike (among others) all fall into the same habit of reading Watchmen the way Moore intended the book to be read, as an anarchist critique of superheroes and authoritarianism. But it seems to me that like many other works of art Watchmen is latent with contradictory meanings that undermine the authorial intent. It’s a story where the superheroes act and ordinary people re-act (just [as] in Shakespeare the tragic hero acts while the secondary characters and ordinary people re-act). Because characters like the Comedian, Ozymandias, and Rorschach are the agents of change and action, they are the figures that engage the imagination. It’s no accident that DC is doing “Before Watchmen” about the early life of the heroes rather than “The Early Life of the token black and lesbian characters who die in Watchmen.”

According to Mike Hunter, the fans who love Rorschach and identify with him are “dimwits” who have an “asinine” reaction. But in point of fact I think such readers understand the narrative logic of Watchmen better than the defenders on this site (Eric B., Noah, and Mike among others) do. These Rorschach loving readers understand that he’s presented as sympathetically as Peter Parker or Bruce Wayne — he’s someone who has been wronged and he’s ready to kick-ass. When you read a superhero story, your natural instinct is to identify with such a character, even if he’s a fascist loser. Moore’s authorial intent can’t overcome the logic of the genre, in part because Moore’s skills as a pastichist makes him do all the right genre moves to win over readers.

As for Rorschach being a complex character, the fact is that he takes the law into his own hands and beats people up. Am I [correct] in thinking that he also kills people? So he’s a thug — in real life he’d be horrifying but in the context of the book he’s sympathetic — because the book ultimately accepts the logic of the superhero genre. Also self-pity is a big part of the fascist mindset but Moore does not sufficiently distance us from Rorschach to make us critical of his self-pity — rather we share in it. Again, Clowes handles this better in The Death Ray.

(9) [I was just looking at Katherine Wirick’s piece on Rorschach as a rape victim.] It’s a very smart piece. This is not meant as a knock on Wirick (who makes a convincing case for how Rorschach should be interpreted) but I’m wary of accounts of fascism that start with the victimization of fascists. To the extent that fascists are victims or losers, its because they’ve benefited from systems of privilege (capitalism, imperialism, patriarchy, imperialism, racism) which are being challenged.

Mike Hunter: “…there are plenty of examples of humble, noncostumed humans, who are shown as moral, caring, striving to do the right thing, for all their final fate. The cops and psychiatrist who as their last act moved to stop the fight of the lesbian couple. The way the salt-of-the-earth newsstand vendor, as death moved to overwhelm the city of New York, protectively embraced the black kid who’d been hanging out reading this pirate comic. As their bodies merged and dissolved, tears came to my eyes…”

(10) Non-superheroes in Moore’s universe can try (unsuccessfully) to defend themselves but they can’t make their own history or challenge the power that be. (11) It’s fairly common in movies to spend a few moments with sympathetic figure — say a cop who is about to retire — who is then killed. This is done to establish some moral gravitas or emotional engagement on the cheap. In terms of narrative, these characters are created in order to be killed. That is what Moore is doing — being talented he does it well, but it’s still a relatively cheap effect.

In the real world, thankfully, ordinary people can and do stand up to tyranny, even if they are often defeated. (12) [In] 1984 Winston Smith and Julia do resist the totalitarian state. They are ultimately defeated and brainwashed (in a horrifying way) but despite the defeat the book hinges on the idea that there will be some internal resistance. There’s no resistance in the world of the Watchmen, only futile attempts to save a few lives in the fallout from the actions of the superheroes — but no attempt to change the system whereby the superheroes dominate or the geopolitics the superheroes are embedded in and support.

(13) Despite repeated attempts to enter into it sympathetically, I can’t accept the characters in Watchmen as human beings. Moore has them do all sorts of improbably things (like a woman falling in love with her rapist). They seem like puppets to me. There is also sorts of violence in Watchmen — rapes, murders, and even the killing of millions — but none of [this] effects me as I read the book because none of the characters are able to stake out the emotional claims that are necessary in order for us to care about the fate of fictional creations. It’s telling that many readers seem to fantasize about being Rorschach. If the violence Rorschach unleashes had any felt reality, those readers would be terrified of Rorschach and regard him as a psychopath.

(14) That’s why I brought up Clowes. He has the ability to create characters that you can both empathize with but also see their flaws and limitations — no one wants to be Andy in The Death Ray, although despite how horrible he is he remains recognizably human. The middle-aged Andy is pretty much an asshole, albeit one gifted (as many Clowes characters are) in self-justification. But the young Andy was more sympathetically presented — he’s someone in flux, with good traits and bad. The story is about the process where the young Andy starts on the road that turns him into the middle-aged Andy. And Clowes sense of how characters are shaped and formed by their environment seems much more plausible that Moore, who has a crude pop-Freudian understanding of personality formation (i.e. trauma leads to violence). The same applies to Lint — the process by which Lint becomes who he is, the way he’s shaped by his memories and decisions as well as his lifelong traits, is very finely handled. By contrast, Roscharch is just a high-brow version of The Punisher or Wolverine — a psychopath you can root for!….I just don’t see the Moore of Watchmen as being anywhere near the writer Clowes is.

(15) [As for] the rape of Sally Jupiter, just in terms of Watchmen itself, it’s a fairly minor lapse but becomes a bit more problematic because of the pervasiveness of sexualized violence towards women in Moore’s work. Again, I think there is a charitable interpretation that can be made: Moore is interested in creating genre-deconstruction and pastiche of genre material. The “damsel in distress” is a key figure in many genres and Moore is simply bringing to the fore the rape subtext that is latent in many narratives. But it’s possible to take a more critical stance towards Moore’s handling of rape as well.

(16) [My] objection isn’t that Watchmen is a superhero comic. I have a high regard for the superhero comics of Kirby, Ditko, Eisner, Cole, and others. As I noted elsewhere Kirby offers a clue as to what bothers me about Watchmen. In all his comics Kirby created an open universe that could be imaginatively inhabited and colonized. Moore’s genre work, by contrast, seems not just closed by the airtight structures the author has created but even suffocating in the way they don’t allow the characters any freedom from the dictates of the plot and theme. A character like Maggie (in the Locas stories) or Andy (in The Death Ray) has the ability to surprise you even as they remain true to their nature. By contrast, Moore’s characters are merely pawns in the service of his agenda.

It seems to me that the critique [recently] leveled against Jaime Hernandez applies much more to Watchmen. Watchmen really is a giant Easter egg hunt. Moore is quite clever at packing his narrative with lots of little clues that readers can spend endless hours matching up in order to solve the puzzle. But I find this type of cleverness to be an arid and gimmicky exercise because the story is so utterly devoid of humanity, so utterly contrived and constructed.

____________

Okay, I think that’s it. Thanks to Jeet and all who participated. It was a fun discussion. (Noah B.)

Well said, Jeet.

I didn’t read “Watchmen” until relatively recently.

I was stationed on the island of Okinawa from 1985-1991, and thus never saw it until many years after the initial publishing brouhaha.

When I finally did sit down to read it, after I was done, I was kind of wondering what all of the fuss was about.

Don’t get me wrong — I enjoyed it. But I have to wonder if the reason “Watchmen” became iconic was because it was a quantum shift in superhero comics during the 1980s — today, not so much.

I guess a parallel is, say, “Action” #1, which was a quantum shift in comics in 1938, but by today’s standards, it’s quaint, at best.

Mind you, I’m not comparing Moore’s writing to Siegel’s — taht’s not fair to Moore, whose writing sophistication level far exceeds that of the Superman co-creator. But the IMPACT on the audiences of each era may be similar.

Just thinking out loud.

So, the “mostly of historical interest,” argument huh? Ouch.

Moore’s genre work, by contrast, seems not just closed by the airtight structures the author has created but even suffocating in the way they don’t allow the characters any freedom from the dictates of the plot and theme.

This kind of makes me want to read it…

Since I couldn’t do it before Noah closed the other thread, I want to congratulate Jeet for his participation in the book “Too Asian?”.

I actually opened the other thread back after a breather…but hopefully Jeet will see it here.

On Moore’s never-ending trips back to the well of sexual assault on women: the lifetime incidence of assault on women, even in the developed world, is shockingly high. The International Violence Against Women survey reported a figure of 57% in Australia who had been sexually and/or physically assaulted at some point in their life. In the US, the Centers for Disease Control have reported a figure of 50%.

Granted, the figures would be higher for women in Moore’s work, but you could make the case that he’s just being true to life here.

“I can’t accept the characters in Watchmen as human beings….They seem like puppets to me.”

This is a common thing to say in literary criticism, but isn’t it an odd thing to say because they are characters, not human beings, and they never will be unless science invents a way to materialize our thoughts. In any case, Heer’s thoughts suggest to me that the real question is this: why do we read or watch stories? Heer seems to suggest that he reads to learn life lessons. But is there really just one answer?

I don’t necessarily agree that individuals have lots of control over history, or that Dan Clowes is a genius, or that rape is a topic to avoid discussing.

But I like Jeet’s critique of the sympathetic fascists and the fatalistic politics. If mass slaughter isn’t a major ethical flaw, then what is?

@Bert Stabler. It’s not a matter of believing that “individuals have lots of control over history” but rather believing that humans as a collectivity do have some say over their destiny and aren’t just puppets (as they are in Watchmen). On this question, I always liked the statement from Marx (or was it Engels) that people make their own history but not under the conditions of their choosing.

Nor did I say that “rape is a topic to avoid discussing.” I don’t even really object to Moore’s handling of rape so much as I’m troubled by it — troubled by the way he keeps going back to rape and keeps using it to spice up some fairly conventional pulp plots. Even here, I’m open to the argument that Moore is actually satirizing the “damsel in distress” motif that is a bedrock of pulp fiction by showing the actual grim things that happen to damsels.

As for Clowes, I don’t think its necessary to think he’s a genius to appreciate that he handles similar material better than Moore.

“troubled by the way he keeps going back to rape and keeps using it to spice up some fairly conventional pulp plots”

Is he spicing up the plots? Or is he addressing the way that pulp’s fetishization of force and sex is implicated in some brutal real world consequences?

It doesn’t have to be one or the other, of course….

I haven’t read any Clowes since David Boring, Velvet Fist, and Ghost World. So I’ll defer on that one.

That’s a good Marx quote. I just think dissidents (and most celebrities) are fetishized for ideological reasons more often than particular people have even marginal effects in mass society. But certainly no reason to leave it all to superheroes.

Women’s bodies are used as phalluses in art of all kinds, but the idea that its spiciness in Watchmen is highly irresponsible doesn’t totally convince me.

Which is less the case with his take on justified violence in general, which is why I think your (Jeet’s) objections are legitimate.

Bert, are you saying that Watchmen justifies Ozymandias’ mass murder at the end? Because I really don’t think that’s the case (it’s much, much more ambiguous than in V for Vendetta, anyway; part of the reason why I prefer Watchmen.)

Actually, that part of it doesn’t really seem very ambiguous. Veidt’s actions are never justified or justifiable in the book. It’s clear that he spurs on the approach of nuclear war and then acts to avert it. He assumes war is inevitable, but there’s no indication that he (or the Comedian) is right about that. He takes it upon himself to “save” everyone from something which may well never have happened in the first place…

And that’s just on a plot level. Obviously killing millions of people is horrifying in itself.

Doing so based on a presumption about the future is clearly not meant to be seen as “justifiable” or justified.

It does come across as more justified in V for Vendetta, but even there, it’s fairly ambiguous. V’s torture of Evey definitely makes you question V and his behavior, even if his “revenge killings” don’t.

I need to re-read Watchmen… my last recollection was that both Veldt and Rorshach come off sympathetic albeit opposed. Someone’s got to massacre, someone’s got to torture, cycle of life. More existential perhaps, Niebuhrian if you will, but maybe there’s a strong indictment in there.

I just reviewed the plot on Wikipedia– Veldt is peobably not an entirely lovable tycoon-emperor, but I still remember feeling as if all the misery sort of balanced out rather bleaklky. Still a good story and all.

There is a condemnation or at least critique of Ozymandias/Veidt but it comes on pragmatic grounds — i.e. his scheme probably won’t work in the long run (i.e. Dr. Manhattan’s statement that nothing ever ends and the survival of Rorshach’s diaries). But as I said, this condemnation is relatively mild — most of the surviving heroes agree to go along with the scheme which only Rorschach (a highly dubious character and borderline insane) condemned outright. And within the book Ozymandias/Veidt is not (pace Noah) presented as an idiot. He’s presented as the smartest man in the world and his intelligence is respected by all the other characters, even if they morally disagree with him. Within the logic of the book, his scheme is presented as perfectly rational, if also cruel — and only flawed in the sense that all human endeavors are flawed (i.e. subject to being unraveled and thwarted by unseen contingencies).

Yep. Niebuhrian, Obamanian, pragmatist. The half-life logic of “nothing ever ends” pretty much dispenses with earthly justice.

I think Veidt’s definitely working in a Niebuhrian paradigm…but I don’t think that ends up validating Niebuhr. It’s more than Veidt not being entirely lovable; it’s that there’s plenty of evidence in the book that he’s a fool and a megalomaniac, and that his gleaming new empire is a tomb (his name is Ozymandias, after all.)

Or to put it another way…if Obama and his drone strikes are Ozymandias, then Obama comes off looking pretty bad.

I’ll agree with Jeet it’s ambiguous. Ozymandias is very smart and very powerful…but so’s Obama. So’s anyone who’s going to get into a position of massive power and influence.

There is a pragmatic criticism, but there’s also (as Jeet suggests at the end of his comment) a suggestion that pragmatism in itself is a flawed philosophy. Veidt’s error is to forget that all human endeavors are flawed, that the world is not ultimately in our control, and then to follow through on that error by murdering millions of people.

In terms of moral condemnation, Rorschach (the unwavering nutcase), condemns him, Laurie and Dan (the hapless everyday witnesses) punt, and Dr. Manhattan somewhat approves — but, you know, it’s not especially clear in the logic of the story that Dr. Manhattan is a whole lot more sane than Rorschach is. His reaction to Veidt is similar to what he does when the Comedian shoots his pregnant girlfriend; he just shrugs. Is that because he has a wider perspective, or is it because he’s a moral monster?

I don’t mean to say that it’s entirely clear; I think Eric maybe goes to far to the other extreme. But the comic is definitely not unambiguously cheering for drone strikes or invading Iraq or whatever other superpower deus ex machina is supposed to lead to utopia.

The one unbelievable and perhaps problematic characterization here is that Veidt actually feels guilt for what he’s done. The folks who actually commit these kinds of atrocities rarely do, as far as I can tell.

Veidt feels guilty… but are we seriously claiming that someone like Truman, in private moments, didn’t feel guilty about dropping the A-bomb. Do we know this? Maybe I’m too charitable about human nature (something I’m rarely accused of, btw), but this seems unlikely to me.

Btw, the best evidence of my claims above is the “mise en abyme” of the pirate narrative. There, the sailor “predicts” that the Black Freighter will come to Davidstown, wreaking havoc, etc. He acts on that prediction, gets there ahead of the ship and starts wreaking havoc himself on what he believes to be the pirates…but actually he kills/hurts his own family, friends, and neighbors. The scenario is an exact parallel to Veidt’s. Veidt makes a prediction and acts on it, killing and wreaking havoc, etc. The sailor’s actions turn out to be based on an incorrect prediction (and he sails off the hell on a road paved with “good intentions”), and he commits deeds he never had to do. — To me, this is a clear indication that Veidt’s actions are themselves based on a false prediction and that the giant squid attack was unnecessary. The parallel between Veidt and the sailor is obvious in other ways (both sailing off to “save their worlds” on the backs of the dead)…and it remains so here. Like the sailor, Veidt has “good intentions” but commits actions that are not only horrible, but are also unnecessary on based on false premises.

The only thing redeeming about Veidt is that he definitely feels like he’s doing the right thing. He actually thinks he’s “saved the world”–but it’s pretty clear that he’s wrong about that.

Dan, Laurie, et. al. don’t approve of Veidt’s actions. They simply say that it’s “too big” for them to decide. Also…it’s already happened. Blowing the whistle doesn’t bring back the dead, but it might screw up any potential positive consequences. I’m not saying I agree with this logic…but that’s the basic situation. Nobody ever actually says, “Hey, it was a good idea…,” including Manhattan.

People do try to make the argument that pragmatist realpolitickers feel more anguish about their crimes (even Zizek with Stalin a little) than crazy fanatics (Rorshachs) or mystics (Blake). Tough decisions are tough, don’t you know.

And ultimately it’s all for naught because people are hopeless, which seems not that far from capitalist deterritorialization via transcendent annihilation.

Also…I find it hard to read the book as “Rorschach vs. Veidt” in philosophical terms, though that’s how it seems to come off in the end. Rorschach is much like Veidt… He kills the few to (supposedly) protect the many….He supports Truman’s dropping of the A-bomb (a clear parallel to Veidt’s actions). Both take their own personal morality/justice and apply it to the world with no external sanction. In many ways, they’re the same guy. (One major distinction is that Veidt is willing to sacrifice the innocent, while Rorschach is only willing to kill the ‘guilty’—but since they’re guilty only by his judgment, the distinction isn’t as stark as it might appear).

Veidt actually references the black freighter story explicitly when he’s talking about his guilt.

I’ve read a bit about Truman. I’ve never seen any evidence that he felt any guilt after dropping the bomb. He was convinced that more (or at least some) americans would die in a land invasion. And when you have a weapon in wartime, you use it; that’s the pragmatic calculus.

Truman wasn’t terrible as presidents go, but that still leaves plenty of room for him to be a moral monster.

This is analogous to The Watchmen as I see it.

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_xRFNBWST25E/TPiI4x4RLxI/AAAAAAAAGOs/-2s9rgKBBlw/s1600/McDonalds+Toy+Art+Car.jpg

Yes, Veldt and Rorshach (and maybe Jon) are supposed to be the same person, which is an intriguing and subtle idea. But yeah, Veldt feels deeply, so he’s the most sympathetic. Because, as Benjamin noted, bourgeois capitalism is the closest thing to sustained mass anarchy history has known, and Moore likes anarchy.

Oh, and the art car reminds me more of Geoff Darrow.

Veidt’s the *least* sympathetic, though. Who likes Veidt? He’s a self-righteous asshole. He even murders his cat, for goodness sake. I seriously doubt many people would choose him as a favorite character.

Murders his cat… well, that’s hard to argue with. But I’m sure he did it for freedom/deeply vital strategic interests.

Veidt also profits from the squid-bombing, tailoring his corporate advertising to capitalize on the new utopian mood.

When I read “The Call of Ctulhu” a couple of years ago, I thought, “This is just like the end of Watchmen,” but when I Googled around, no one else seemed to have made that connection. Jeet Heer is the first person I’ve ever seen mention it, and I think it was a deliberate reference on Moore’s part.

The cat murder was for nothing. He sacrifices the cat to kill Dr. Manhattan, but it doesn’t work — and as Dr. Manhattan points out, it was pretty easy to see from the get-go it wouldn’t work.

I was being snide about the strategic interests, but of course he thought he had some. I agree with Jeet that Veidt is not a hero, but is sort of tragically yet comically endearing– Hamlet meets Dr. Evil meets H.P. Lovecraft.

The Black Freighter story-within-a-story is the best evidence that Ozymandias/Veidt is being condemned. I like the obliqueness of the condemnation which undercuts the bluster and melodrama of the main story. Having said that though, as I said before Moore proficiency at using genre tropes overwhelms the critique of genre that he wants to have. Ultimately, Ozymandias, like Rorshach, is cool because he does cool things and wins the post facto acquiescence (however reluctant) of most of the other heroes. The fact that we’re talking about him as if he were Harry Truman, rather than Eichmann, is telling about how Moore stacked the deck to make his horrible actions seem reasonable in the context of the book.

To me, there is a difference between (one the one hand) Truman dropping the A-Bomb on Hiroshima or Obama’s drone attacks versus Ozymandias’ space squid scheme. Whatever you might think of them — and I think Truman was wrong and am divided about Obama — these are democratically elected officials who have all sorts of checks on them and do their actions in public. If the American people were really horrified by Truman they could have thrown him out of office in 1948 (and Obama this year). Alas, few Americans are bothered by either the bombing of the Japanese cities or the drone attack. Still, Ozymandias’ plot is different — he’s the sole mastermind (none of the other participants even know about it) and it is done in secret. There really is no check on him — he’s literally a superman in the sense of being an ubermench — beyond good and evil. Again I think Moore is being critical of Ozymandias but the logic of the book makes his actions ambiguous in a way that I find troubling.

“Whatever you might think of them — and I think Truman was wrong and am divided about Obama — these are democratically elected officials who have all sorts of checks on them and do their actions in public”

They’re democratically elected by Americans. They bombed the shit out of other countries, who didn’t have much say one way or the other, much like the New Yorkers killed by Ozymandias.

I think the 9/11 attacks work as a comparison to Ozymandias as well, if you’d prefer that.

1) Even if we agree that Rorschach is “cool”, I can’t accept that Ozymandias is too — other than the bit where he catches the bullet. He’s a prick, and he comes off as such.

2) The point of the implicit pragmatic criticism of Oz. at the end of the book isn’t that it’s the only grounds for condemning his actions. It’s that even on its own grounds, his master-plan is stupid. If the ends justify the means, they only do so when the means actually produce the ends.

I have to say, I do like the idea that Veldt, Rorshach, Jon are all variations of the same personality type. What united them is they are all isolated individuals incapable of having relationships with other people (whether out of psychological reasons or because, in the case of Jon, they really are non-human). This stands in contrast to the two lovers. And in point of fact, the most human and poignant recurring image in Watchmen is two lovers clinging together against the backdrop of Armageddon — an image taken of course from Hiroshima.

It’s definitely the case that Dan and Laurie are functional human beings, and Jon, Veidt, Rorschach, and the Comedian are all antisocial psychos. It’s why I find Dan and Laurie by far the most sympathetic characters in the story at this point.

You often see people saying about Laurie that she’s defined by her relationships and so she’s not as much of a hero or some such…but of course, she’s defined by her relationships because she’s relatively normal, and relatively normal people are defined by their relationships, rather than being murdering isolated psychopaths like the rest of the characters in the story (except for Dan…who is also defined by his relationships.)

Very nice point about the recurring lovers, too.

Yeah, for me Dan and Laurie provide the heart and moral center of Watchmen, to the extent the book has a heart and moral center. They do counterbalance a lot of things I don’t like about the book.

Hah! They’re definitely the superheroes for the people who don’t really want to read about superheroes. I liked Rorschach best when I was a kid, but as I get older and more boring I much prefer Dan and Laurie.

———————————

R. Maheras says:

…When I finally did sit down to read it, after I was done, I was kind of wondering what all of the fuss was about.

Don’t get me wrong — I enjoyed it. But I have to wonder if the reason “Watchmen” became iconic was because it was a quantum shift in superhero comics during the 1980s — today, not so much.

———————————–

Unfortunately, you didn’t read it when it was the perfect time to read it. It’s still a great work, though nothing could equal the impact of reading this precedent-breaking work when it was new, and undiluted by lesser imitations.

What would the blasé youngsters of today think, seeing Psycho for the first time? Even if they could appreciate the craftsmanship, so many of its tropes have been absorbed into the culture, its once-shocking violence far outstripped, lessened in impact and freshness by countless crappy imitations… (Lucky me, I got to see it in a big old “movie palace”-type theater, the audience what seemed like a major part of the student body of a girls’ school…)

————————————

SD says:

Moore’s genre work, by contrast, seems not just closed by the airtight structures the author has created but even suffocating in the way they don’t allow the characters any freedom from the dictates of the plot and theme.

This kind of makes me want to read it…

———————————–

Kind of Kubricky, the mind-boggling attention to detail; though Moore’s is a far warmer view of humanity…

————————————

Bert Stabler says:

…If mass slaughter isn’t a major ethical flaw, then what is?

————————————–

Tough love? But, seriously…

————————————–

eric b says:

Actually, that part of it doesn’t really seem very ambiguous. Veidt’s actions are never justified or justifiable in the book.

——————————————

Isn’t killing millions in order to prevent the killing of billions and the virtual annihilation of human civilization, a defensible tactic? Like amputating a gangrenous arm to save a body, locking away (or even shooting) plague-carriers to prevent them from infecting an entire population?

——————————————

It’s clear that he spurs on the approach of nuclear war…

——————————————-

No, he doesn’t; and saying “it’s clear” won’t make it so. He sees signs all over of oncoming Armageddon, and figures how to capitalize on the zeitgeist with products to fit those tastes.

——————————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…it’s that there’s plenty of evidence in the book that he’s a fool and a megalomaniac, and that his gleaming new empire is a tomb (his name is Ozymandias, after all.)

__________________________

Heh, heh! Indeed it is:

———————————————-

Ozymandias

by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

I met a traveler from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

————————————————

————————————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

The one unbelievable and perhaps problematic characterization here is that Veidt actually feels guilt for what he’s done. The folks who actually commit these kinds of atrocities rarely do, as far as I can tell.

————————————————-

Oh, it’s not so bad; he makes himself feel guilt, because he thinks he should. “I’ve made myself feel every death…”

————————————————-

eric b says:

…Veidt’s actions are themselves based on a false prediction and that the giant squid attack was unnecessary.

————————————————-

How so? Was all-out nuclear war not terrifyingly imminent? Has the U.S. and Russia decided to “bury the hatchet” and not told anyone? I must’ve blinked and missed that part…

————————————————–

The parallel between Veidt and the sailor is obvious in other ways (both sailing off to “save their worlds” on the backs of the dead)…and it remains so here. Like the sailor, Veidt has “good intentions” but commits actions that are not only horrible, but are also unnecessary on based on false premises.

————————————————–

And Veidt tells Jon at the end, he has dreams of swimming toward what is clearly supposed to be the Black Freighter (though it’s never actually mentioned); to join the damned murderers aboard like the hapless chap in the pirate comic. (Ah, I see Noah’s beat me to mentioning this…)

————————————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Veidt’s the *least* sympathetic, though. Who likes Veidt? He’s a self-righteous asshole. He even murders his cat, for goodness sake.

————————————————

Haw! But, (as I’d argued earlier), that cat was a devil! Well, symbolically, anyway:

————————————————

Mike H. says:

Recently, was reading again Steven King’s The Mangler in a horror-story collection, and was struck by mention of a demon named Bubastis.

As we all surely recall, that was the name of Ozymandias’ pet, a huge, genetically-modified lynx. Historically, supposed witches, as one of the perks for having sold their soul to the devil were given a demon companion/assistant in animal form, usually that of a cat.

(Looking online for more info, was struck by how Bubastis’ appearance made this “familiar” symbolism blatant; his genetic modification making his ears resemble horns, fur predominantly red, the stereotypical color of demons: http://watchmen.wikia.com/wiki/Bubastis )

Though the supernatural does not figure into Watchmen (at least not openly; with the book’s many layers, I’m reluctant to say nay), this is another way for Moore to indicate that with his murderous world-saving scheme Ozymandias has, in effect, sold his soul to the devil. (Damned himself, as more clearly indicated by the recurring dream of approaching a Black Freighter-like ship he mentions to Dr. Manhattan towards the end.)

————————————————-

————————————————-

Jeet Heer says:

The Black Freighter story-within-a-story is the best evidence that Ozymandias/Veidt is being condemned. I like the obliqueness of the condemnation which undercuts the bluster and melodrama of the main story.

————————————————–

Just one of the countless brilliant things about Watchmen!

—————————————————

Having said that though, as I said before Moore proficiency at using genre tropes overwhelms the critique of genre that he wants to have.

—————————————————

Darn that pesky talent! A good point, though. I’m reminded of how young, gorgeous and charismatic Marlon Brando made Stanley Kowalsky far more sympathetic than Tennessee Wlliams had intended.

———————————————–

…in point of fact, the most human and poignant recurring image in Watchmen is two lovers clinging together against the backdrop of Armageddon — an image taken of course from Hiroshima.

————————————————-

Dunno about the “of course” — there were only isolated human shadows ( http://www.thehypertexts.com/images/hiroshima-shadow-2.png ) not those of pairs of lovers, burnt into walls by the atomic explosion– but Dan has a nightmare of him and Laurie ending up like that; there are the “ominous,” disturbing silhouettes of embracing lovers painted on building walls; the newsstand owner covers the pirate-comic-reading kid in a protective embrace, their shapes merging and dissolving in the blast from Veidt’s attack on New York…

————————————————

…To me, there is a difference between (one the one hand) Truman dropping the A-Bomb on Hiroshima or Obama’s drone attacks versus Ozymandias’ space squid scheme. Whatever you might think of them — and I think Truman was wrong and am divided about Obama — these are democratically elected officials who have all sorts of checks on them and do their actions in public. If the American people were really horrified by Truman they could have thrown him out of office in 1948 (and Obama this year). Alas, few Americans are bothered by either the bombing of the Japanese cities or the drone attack.

————————————————-

Not to overvalue the sensitivity of the American people, but as this story of the suppression of films showing the true horrors of Hiroshima makes clear — http://www.cddc.vt.edu/host/atomic/hiroshim/index.html — it’s not as if the vast majority of the American people ever get much more than a carefully censored, sanitized and “spun” view of our government’s less-noble moments.

(More Hiroshima horrors, not for the faint of heart or expectant mothers, at http://therearenosunglasses.wordpress.com/2009/10/16/atomic-shadows/ and

http://www.gensuikin.org/english/photo.html )

Well, you’ve certainly proved that at least one reader can seriously see Watchmen as justifying mass slaughter. Point to Jeet.

Oops, this is the link to the “suppression of films” story: http://rogerhollander.wordpress.com/tag/nuclear-warfare/

I think Jeet problematized Moore’s aestheticized politics a smidgen. But you know a real Holocaust justification in sci-fi is Frank Herbert’s God Emperor of Dune. That’s some creepy tedious Nazi stuff. Actually, it’s no Watchmen but it’s entertaining.

Aesthetic elitism, which Moore has perhaps critiqued devastatingly and/or an ambivalent relationship to, is a fairly staked-out political viewpoint in the modern era. Flaubert once said something about he cared far less about a poor man than about the vermin that lived in his clothing.

Didn’t read all of this….but, in response to Mikem Veidt predicts nuclear war in the mid-1990’s…then hurries things along so that he can control it (by getting Jon off planet mainly). That is, he causes the mid-1980’s approach to nuclear war (invasion of Afghanistan, etc.). He thinks (based on evidence) that the war is coming in the ’90s, but if it were “inevitable” that it were coming then, he couldn’t make it come earlier. He causes the immediate circumstances the book shows. Was nuclear war ACTUALLY inevitable in the 1990’s. Well…obviously not in our world. In the Watchmen world….we only have Veidt’s word for it. He spurs things along to have more control…i.e., he causes it.

And all of that is clear enough if you read closely. Veidt has a chart predicting war in the mid-1990s (Rorschach and Dan discuss it)….it’s a chart that shows his research and predictions. But it never happens…thanks to him. (Reread it Mike–I’m sure you’ve read it tons of times—but if you look for that bit, I promise you’ll find it)

———————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

Well, you’ve certainly proved that at least one reader can seriously see Watchmen as justifying mass slaughter.

———————————-

With the world situation as shown in the comic, the “atomic clock” ticking ever closer to Doomsday, blood pouring ever farther down it as each issue came out (The suspense! BTW, I lived through the Cuban Missile Crisis; as I imagine few others here aside from Russ recall, it was an…unsettling time.) Moore surely intended Ozymandias’ plan to come across as justifiable in a “lesser evil” fashion, even if horrifying.

To just have him be, and for us to simplistically see, Ozymandias as just another Nazi mass murderer…

(As Jeet says we should do — “if we take the deaths in Watchmen seriously we should regard Ozymandias as a moral monster, a veritable Eichmann” — trying to push Watchmen readers into having simplistic reactions to what are actually morally-complex/ambiguous characters. Indeed, he wants us to see Ozymandias in the Mr. A black-and-white fashion that Rorschach sees him! Then in the next sentence, he criticizes the book for having qualities which are “pulpy,” “comic-book-y.”)

…is to “dumb down” that aspect of the Watchmen far below what was actually achieved. Sure, Ozymandias has many of the trappings and qualities of a stereotypical comic-book or James Bond movie supervillain; his Arctic lair even reminding of the Fortress of Solitude.

But one of the things Moore did was not only to use genre tropes and genre-type characters to explore moral and philosophical questions, but to depict those in an infinitely more interesting and complex fashion than had ever been done before.

(In contrast, even the ultratalented Chris Ware’s “Super-Man” character and Clowes’ Death Ray critique of genre tropes and characters are, if astringent, far more limited. In the latter case, the critiques are, “power corrupts” and “evil is banal.” Who’d’ve thought?)

Making Ozymandias just a plain ol’ Evil Mass Murderer would delete many of the fascinating nuances and “sides” to the character and his actions than the book clearly laid out.

———————————-

Point to Jeet.

———————————-

Ahhh, “even a broken clock tells the right time twice a day”!

———————————

eric b says:

…Veidt…spurs things along to have more control…i.e., he causes it.

…(Reread it Mike–I’m sure you’ve read it tons of times—but if you look for that bit, I promise you’ll find it)

———————————

Thank, I will! (Every time I read Watchmen I see at least one new, significant detail I’d never noticed before…)

So maybe Veidt is the original Hooded Utilitarian! Huh? Eh?

Btw, I agree with Mike that it comes across as fairly ambiguous. There is an argument to be made for Veidt’s point-of-view. The material that undercuts this view is, as Mike says, subtly presented. I do think the balance of evidence is against Veidt, but it is “in our hands” to ultimately decide…according with RSM’s “Rorschach blot” view of the book.

I always have students who think Ozy is justified in the book (usually, though, they are not the best students).

Ouch! Do your good students talk about the difference between diagetic and non-diegetic justification? That’s always kind of a thing with tragedy. “Macbeth, don’t listen to your wife! She doesn’t have your best interests at heart, and she’s also an invention of a patriarchal discourse!”

“Didn’t read all of this….but, in response to Mikem Veidt predicts nuclear war in the mid-1990?s…then hurries things along so that he can control it (by getting Jon off planet mainly). That is, he causes the mid-1980?s approach to nuclear war (invasion of Afghanistan, etc.). He thinks (based on evidence) that the war is coming in the ’90s, but if it were “inevitable” that it were coming then, he couldn’t make it come earlier. He causes the immediate circumstances the book shows.”

Eric, I don’t think I agree. The 5 minutes to midnight symbolism of the clock occurs in the first scene with the comedian button, before Jon leaves the earth. The set pieces them-self are telling us the world’s heading towards kablowie. It’s bigger than Veidt’s theories or Veidt’s plans.

The fact that Veidt is aware of the pirate story undermines the idea that its commenting on him. Its far more ambiguous because he has self knowledge of that “cautionary tale” so would have at least repeatedly considered whether he’a making an intellectual mistake.

Which doesn’t mean he’s correct- but he is in no way clearly incorrect either. I think Moore described Veidt in interview as enlightened but damned- which is contradictory. Enlightened would mean he’s correct, damned would mean he’s incorrect. I guess he’s both at once, hence the sort of non-ending.

Although one (unintentionally) silly thing about Veidt is he doesn’t know enough about computers to chose a strong password. In retrospect that scene makes him look pretty dumb.

The password thing is really dumb. There’s no way a smart guy like that would be so transparent. Which means either a) he’s not that smart or b) lame plot contrivance… I’m going for b.

I just finished rereading yesterday and… I don’t think Moore sells the impending apocalypse/WWIII (I agree with Eric). I didn’t ever get the feeling that is wasn’t just a case of people being paranoid. I mean… “oh no the Soviets invaded Afghanistan”… Umm, so. We know they did that in the real world and nothing happened (well, stuff happened but not WWIII). For me that’s a real weakness in believing the apocalyptic part of the narrative. Which I guess makes the case for me that Veidt actions were paranoid and monstrous without any justification.

That he gets away with it seems like the triumph of a supervillain. Which I guess one can read as part of Watchmen’s working against genre expectations.

Well, the plot twist is just the thing. What if Veidt wanted the information discovered as part of his total evil/messianic vision? Inky blobs within inky blobs….

I think you can see the computer as a sign that:

1. Veidt wanted them to find him.

2. Veidt is so narcissistically (or however you spell that) obsessed with his stupid superhero identity that he couldn’t resist referencing it in his password (kind of like the Riddler or Penguin or whatever other Batman villain.)

3. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons didn’t know very much about computers when they created Watchmen.

1 or 2 seem feasible — but if I had to choose I’d put my money on 3.

I don’t know– the deceptivenss of the obvious, Purloined Letter style. I’m sure Moore is something of a Poe fan.

————————————-

pallas says:

…The fact that Veidt is aware of the pirate story undermines the idea that its commenting on him. Its far more ambiguous because he has self knowledge of that “cautionary tale” so would have at least repeatedly considered whether he’a making an intellectual mistake.

————————————–

I don’t recall he was aware of, at least that particular pirate story. Even if he hired its writer to come up with wacky SF ideas (young “squids” eating their way out of Mom, for instance) in that island of his…

—————————————

I think Moore described Veidt in interview as enlightened but damned- which is contradictory. Enlightened would mean he’s correct, damned would mean he’s incorrect. I guess he’s both at once, hence the sort of non-ending.

—————————————

Does being enlightened guarantee against making mistakes; decisions with the best aims that end up creating or facilitating horrors? If “the road to Hell is paved with good intentions,” you can be morally correct in your positions/ideology, and still create devastation in this world…

—————————————-

Bert Stabler says:

…What if Veidt wanted the information discovered as part of his total evil/messianic vision?

—————————————-

Or, subconsciously wanted to be found out, stopped or at least punished?

I’d go with Noah’s “3. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons didn’t know very much about computers when they created Watchmen.”

Or, AM could’ve decided that a whole issue devoted to their trying to crack the code would not do much for the story flow…

Veidt talks about the story specifically; talks about climbing towards a black ship. And he surely knew the story; he hired and then murdered its author.

He has visions of the story after the squid is delivered. These visions/dreams are part of the psychic shockwave the squid releases. Veidt doesn’t know the story consciously/explicitly. It’s part of all the shit coded into the squid since Shea was on the island.

Aha! That makes sense. And is quite clever (unlike the password, alas.)

HEy you guys maybe all these questions about Veidt will be answered in an exciting new series coming soon from DC. Wouldn’t that be cool??!! You can also learn all about the giant squid’s backstory, where he gets all his special equipment, and the motives behind his crusade against crime

——————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

Veidt talks about the story specifically; talks about climbing towards a black ship. And he surely knew the story; he hired and then murdered its author.

——————————-

Dunno if it’s elsewhere in the comic (maybe I can reread it again this weekend). I also thought he mentioned “climbing towards a black ship,” but what he actually tells Jon is,

“Well, I dream, about swimming towards a hideous… No. Never mind. It isn’t significant…”

From what we know, surely it’s the Black Freighter that’s his dream-destination, but it’s not spelled out.

And he indeed “hired and then murdered its author,” but does that indicate he knew the writer’s entire corpus? No time to confirm now (my new job schedule’s “normal hours”), but I recall the writer, Shea, as some comics scripters did, went on to a successful career as an SF author, which is likely where Veidt — who doesn’t seem the type to have “wasted his time” reading comics as a kid — knew him from. And thus chose him to come up with alien planet and lifeform images to implant into Squiddy.

——————————-

Eric b says:

He has visions of the story after the squid is delivered. These visions/dreams are part of the psychic shockwave the squid releases. Veidt doesn’t know the story consciously/explicitly. It’s part of all the shit coded into the squid since Shea was on the island.

———————————

No, that mostly-lethal psychic shockwave was limited in range to New York city and its surroundings. Veidt was careful to be well out of range.

And why would a comic-book pirate story be coded into the creature’s brain? It was all intended to be creepy alien stuff that the blast survivors would have impressed into their minds…

“He has visions of the story after the squid is delivered. These visions/dreams are part of the psychic shockwave the squid releases”

I don’t know about that. The actual line from Veidt is

“Jon… I know people think me callous, but I’ve made myself feel every death. By day I imagine endless faces. By night… well I dream about swimming towards a hideous… no. Never mind. It isn’t significant.”

Veidt is saying it at what appears to be the day the squid attack occurs (Rorcshach is killed, Jon peeps in on Laurie and Dan, then walks over to talk to Veidt to say don’t worry about Rorshach). I always read it that he must have been dreaming it before the squid attack… I guess you could try to argue there’s a day missing between pages or something, (Rorshack hangs out at Veidt’s home for a night before trying to leave?) but you seem to be making an assumption (And Veidt studies pop culture for his manipulations of course) and I think “by night” implies its an ongoing thing pre-attack.

Regarding the password thing, I suspect hindsight’s relevant. Everybody knows about the importance of a $tRONGGp@$$werd nowadays, but in 1986 it was less at the forefront of the collective consciousness.

I love Alan Moore, but he’s not perfect. The bit in From Hell where the police try to set some guy up to take the fall for the Ripper murders by dropping him in the water with stones in his pockets, then suggesting to the papers that he might be the guy, falls similarly flat for me. If you were trying to paint the guy as the killer, wouldn’t you trumpet it to the press? “We cracked the case! Victory for us! It was that drowned guy.”

I still think Veidt’s got psychic shockwaves. The squid is coded with all kinds of disturbing shit…everything they could throw into it from the “creative people” on the island. Which included Max Shea. The shockwave kills all the New Yorkers, obviously, but it’s more minor effects can be felt further away… (I think the book says this somewhere—not explicitly about Veidt, but in general—though I’m less sure about this one).

The crappy password has extradiegetic functions (though it’s stupid diegetically). The “II” in Rameses II is a “rider” which fits into the “Two Riders Were Approaching” thematics in that chapter.

I agree that that’s just a crappy plot device…one of view in the book that creaks… I believe Moore has admitted as much.

Still…we can take it as evidence that maybe Veidt isn’t _that much_ smarter than everybody else, contributing to the reading of his hubris.

I was sick for the last few weeks and so missed my chance to weigh in on some things said elsewhere on a now-closed comments thread. So here is as good a place as any.

Yeah, I like Deathray, Ice Haven and the works of Jaime Hernandez and C. Ware way better than Watchmen—and all the other fetishistic underwear epics that pollute American comics.

I see a lot of hope in the work being done outside the mainstream.

But corporate comics are truly crap product, screw all the “modern myths” drivel and I am ashamed to have contributed even as little as I have to that mound of turds. Live and learn.

Despite this, I still love some of the artists I grew up on, like Toth and Kirby, although in the latter’s case I should point out I don’t like to call him “the King” because I don’t believe in royalty, not in life, in comics or in rock and roll. Yes, Kirby’s art boards rightfully belong to him and his heirs, not the company. The bulk of his originals on the market are stolen work, most of it taken under the watch of the wretchedly vicious Jim Sh**ter. Everything that wasn’t returned to Kirby by Marvel (including the pages given away at the office) should be considered stolen, and that is what in my opinion the Kirby family should be seeking compensation for—but since there is no provenance in comics original art and apparently, no ethics among its dealers, tough.

I was also just sickened to hear that Darwyn Cooke is making half a million stomping on Alan Moore’s back, as John Byrne did on Kirby’s. I found Cooke’s first Parker book so vile and misogynistic that I will never buy another of his works—-and I wonder how he can get anything done with everyone including the comics award judges sucking his dick. That said, I think American corporate comics deserve degraded talents of this ilk. No art involved, just derivative exploitation that leads to loud, bad and unwatchable movies. Okay, that’s it.

It’s good to have you back, James.

Whether or no American corporate comics deserve degraded talent, they sure have it. It’s kind of amazing how bad they are at this point.

In the consideration of the psychic shockwaves argument, keep in mind that Moore’s general philosophy and the construction of the book itself suggests those psychic shockwaves might be felt backwards in time as well as forwards.

One proviso to the post above — as I acknowledged in the original comment thread in response to Eric Berlatsky, my use of the word “token” was unfair to Moore.

Let me also add that James Romberger is a man taste and intelligence!

“But I find this type of cleverness to be an arid and gimmicky exercise because the story is so utterly devoid of humanity, so utterly contrived and constructed.”

Complaining that Watchmen is utterly contrived seems (to me) to be missing the point. It’s like complaining that Finnegan’s Wake is crazy gibberish (or something).

But still – nice discussion. And really like all the comments (even if I don’t agree with half of them).

I showed this article to my friend.

Here’s what he said:

so basically it wasn’t enough like his social studies degree?

the whole eichmann para makes the no sense. i don’t get what more humanity means, other than, what, it should have been a bit more wussy?

so fanboys wanna be rorshach. fan boys wanna be the doctor in human centipede. there’s no accounting for idiots. doesn’t make rorschach the hero.

here’s the problem with ppl like heer. they think art’s about a message when art’s about ambiguity/ambivalence/play. rorschach is both wolverine style superhero and ugly psycho, both guy to feel sorry for and fascist with repellant beliefs. MAYBE THAT’S THE POINT (copyright me)

plus, his account of the cold war having ended because of People Power (cut to inspiring 80s montage of fall of berlin wall) places him in the category of moron.

what is a dan clowes’s death ray and is it a good thing?

also – urgh god i hate it when people think they’re being smart when they’re being stupid – in the comments the author’s talking about ozymandias’s plan being sypmathised with coz he’s smart and everyone considers him as smart and the only problems with it that moore shows are pragmatic ones (rorschach diary, nothing ever ends etc) BUT THEN WHAT’S THE FUCKING POINT OF THE BLACK FREIGHTER THAT RUNS THROUGH THE ENTIRE BOOK.

Jesus.

hmmmm! for some reasons there’s this story about a sailor who, in an attempt to save something he loves from bad guys, literally rides on the backs of the dead and becomes a monster and loses his soul. i wonder if it’s meant to have anything to do with the supervillain who dreams of a fucking black frieghter.

eh, probably not. i did politics at universty by the way. look, i will mention marx here: marx.