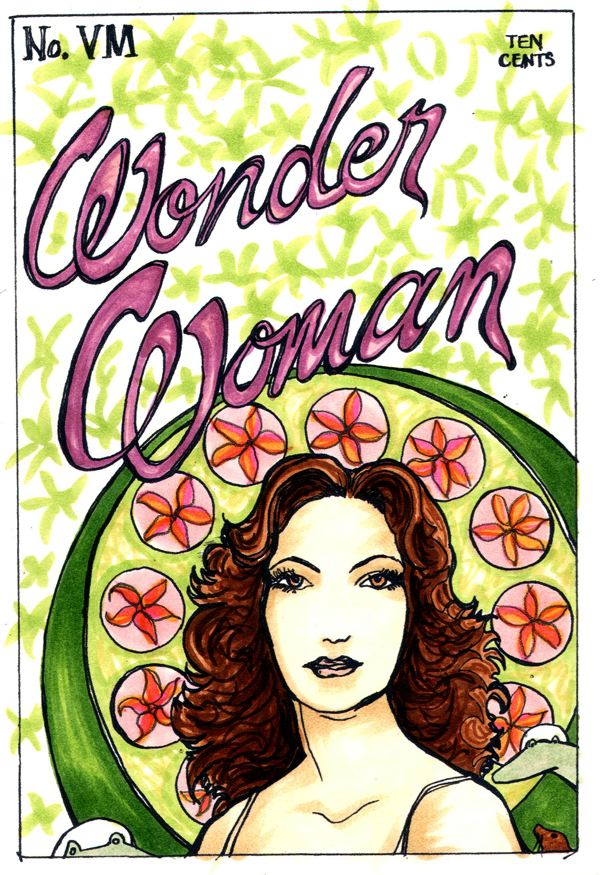

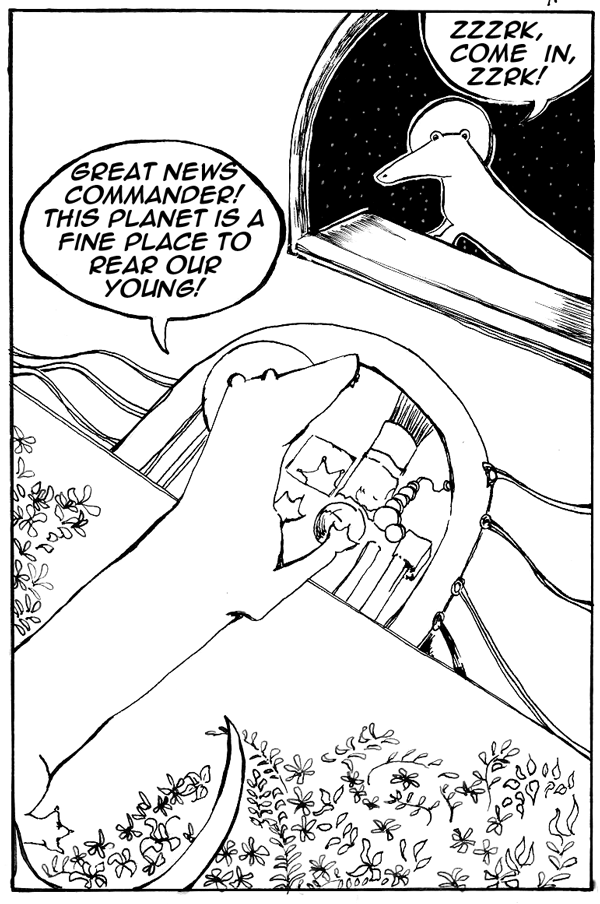

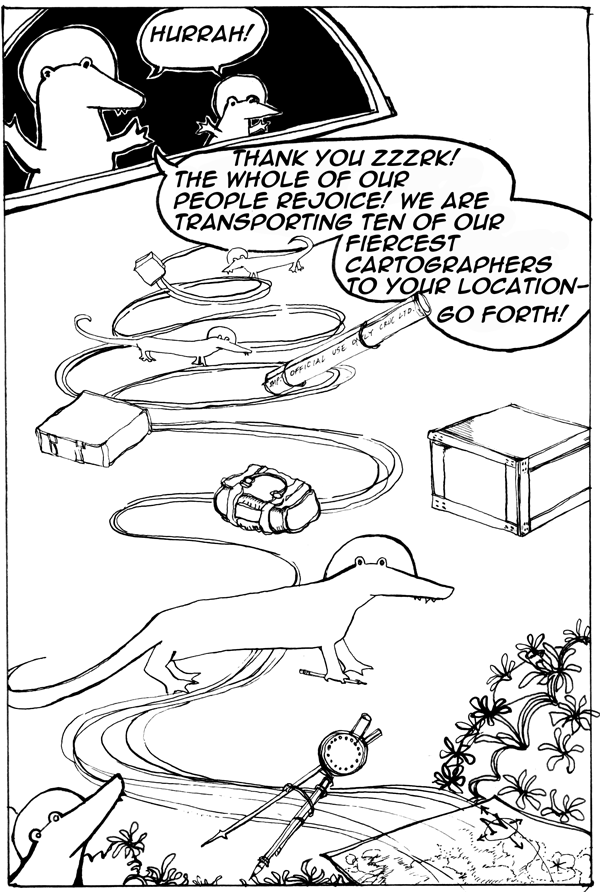

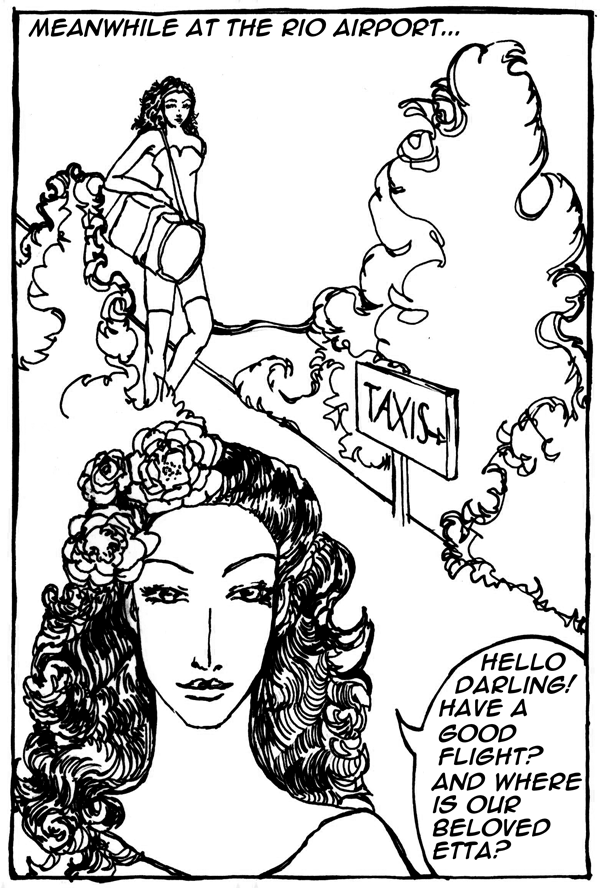

Sometimes a character feels at odds with the fictional world that houses her. I wish I liked Wonder Woman as much as I like Wonder Woman. I’d like to enjoy the super-heroine’s pluck and good cheer as much as I do her robust curves and lustrous black hair. Does this make me a bad feminist? Maybe. But it’s not that Wonder Woman’s athletic feats leave me cold. It’s her virtue that gets me down, just as her good deeds land her in aircrafts that plummet and boats that sink. Of course, she always pops back up, but it’s precisely that bounciness that feels so leaden.

Wonder Woman’s look promises a touch of evil glamor, but her dialogue is all perky efficiency. Judging solely by the character’s appearance, I’d expect a cross between Emma Peel and Bettie Page, but once Wonder Woman springs into action, she behaves more like Snow White’s love child with Nancy Drew. Unlike Batman, Spiderman, or Superman, Wonder Woman has no secret desires, no ulterior motives, no glint of malice or hint of weakness. Amazon Diana and Nurse Diana are equally cheerful, brisk, and sane. Wonder Woman’s superpowers don’t warp her; they don’t compensate for shameful deficiencies, nor are they shamefully hidden. They just turn her into a Girl Scout on steroids.

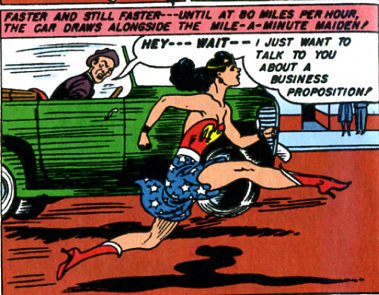

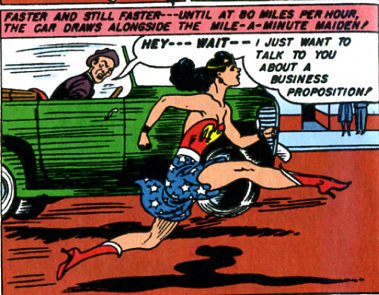

Despite her dark hair, Wonder Woman has no dark side. But why read comics if not to get in touch with the dark side? I, at least, have always preferred watching the bad guys and gals in comics and Disney films. Catwoman and Cruella have the best clothes. So in the panel below, though I admire Wonder Woman’s propulsive arms and extended legs, it’s her compressed, distorted shadow that draws my eye, not least because of the care Peter took in drawing it:

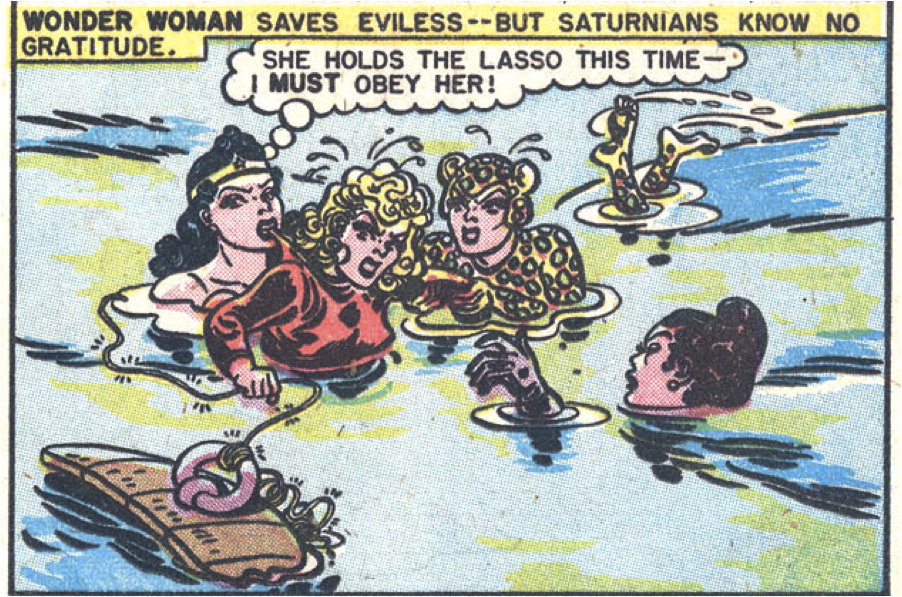

Notice that Wonder Woman is literally not in touch with her shadow in this image, just as throughout #28, “Villainy, Incorporated,” the evil she battles never taints her. Wonder Woman rarely gloats over her defeated antagonists, nor gets carried away subduing them. At one point, Giganta almost makes Wonder Woman lose her temper, but it’s far more typical for our heroine to dash off to get a purple ray machine that will keep villainous ringleader Eviless alive, or to express joy at having saved her from drowning.

If this were Mystery Men, Wonder Woman’s superpower would be agreeableness: by dint of being really, really nice, and kicking some ass, she’s going to make everyone else really nice too.

So it’s no wonder, ha ha, that my eyes keep straying to the less wholesome pleasures Peter has stuffed into almost every panel, such as the colors — especially vivid in the less authentic reprint of #28 in Wonder Woman: The Greatest Stories Ever Told.

The split between Wonder Woman and Wonder Woman manifests itself as a clash of palettes. Wonder Woman (the character) is red, blue and yellow, black and white; the one jarring note is her flesh, a rich coral beige, but we are encouraged to process that as neutral filler, not a color in its own right. Wonder Woman (the comic) is chartreuse and mauve, turquoise and forest green, and uses primary colors only as jarring accents. Sometimes the villains wear red and the Amazon guards don purple and green, but for the most part, to the villains go the subtler, less wholesome color schemes:

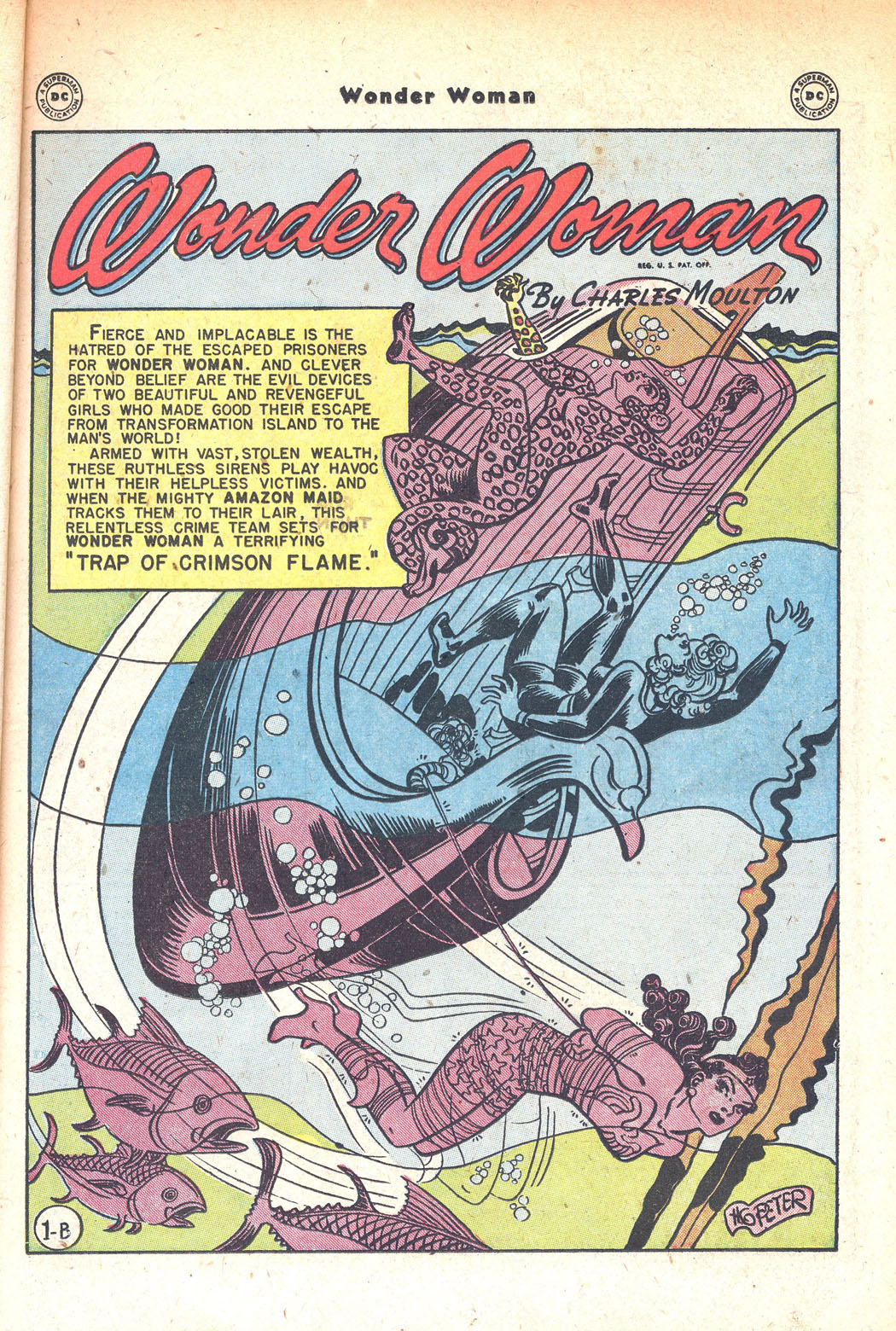

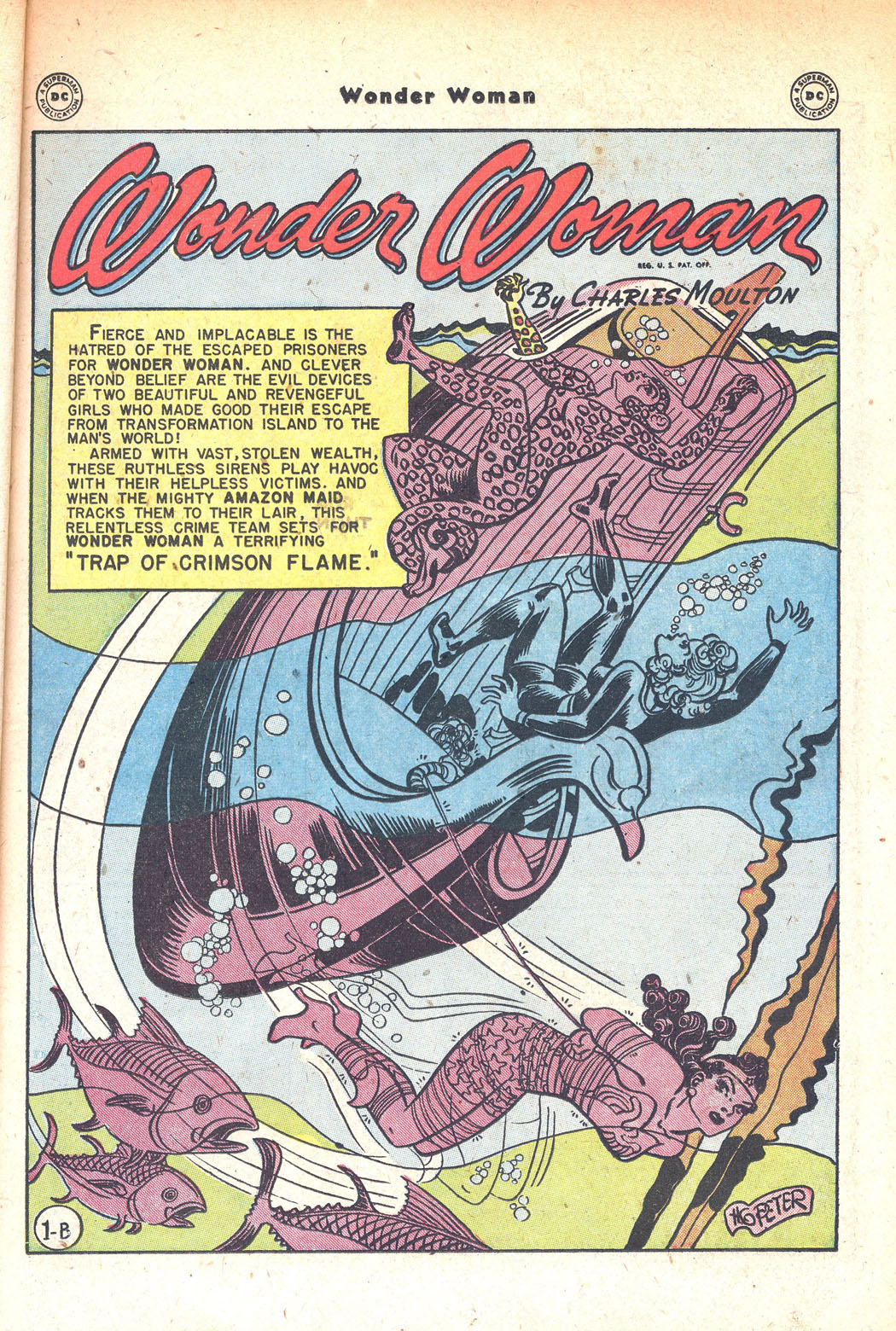

Mauve, turquoise, brown, and a muddy greenish-yellow dominate this panel, overtaking even Wonder Woman herself; her signature red and blue are relegated to the title letters. Only the Cheetah gets to be polychromatic. The color contrast provided by the yellow and brown portion of Cheetah’s arm, seen protruding above the water, gives the panel its depth of field, as do her mauve body parts, especially the sole of her foot, which invades both the print box and the reader’s space.

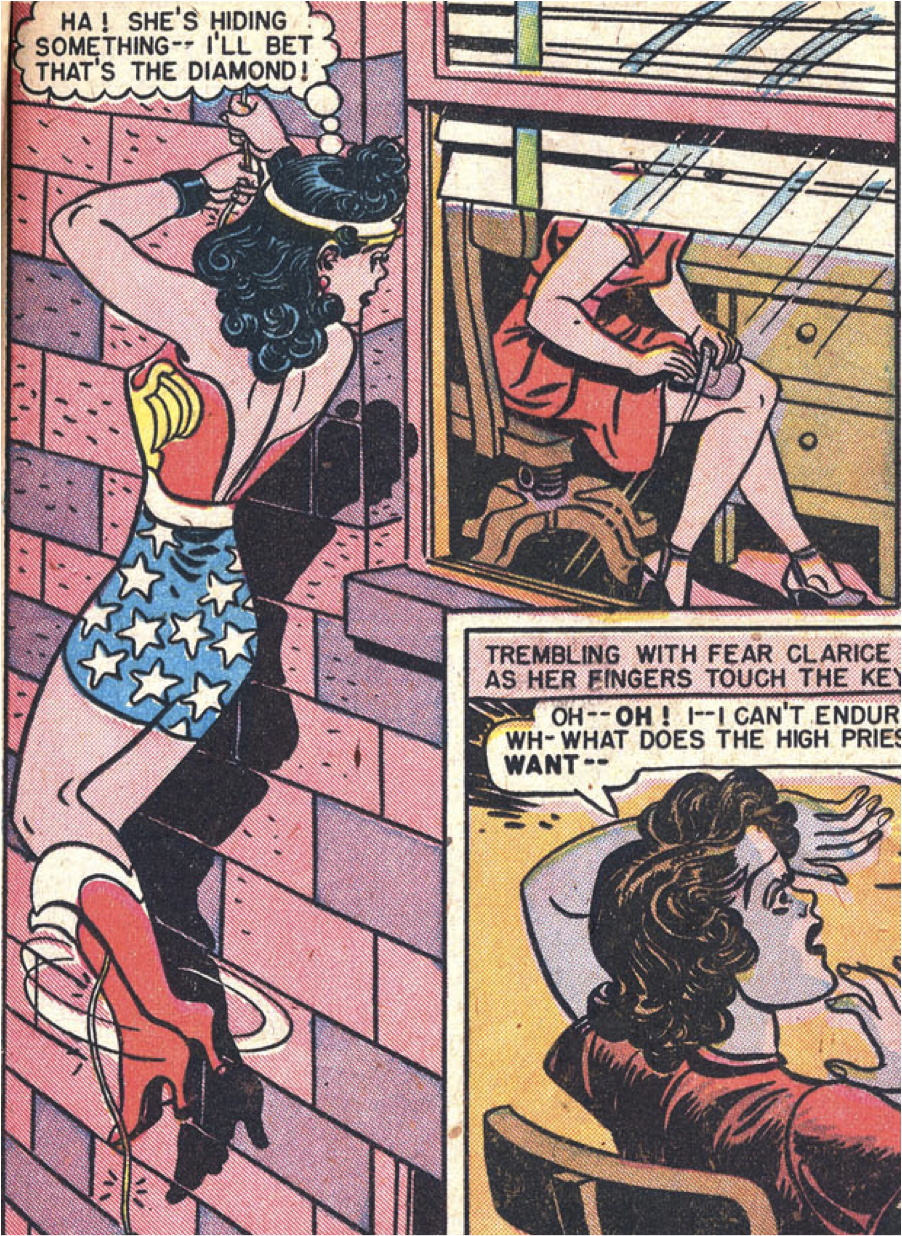

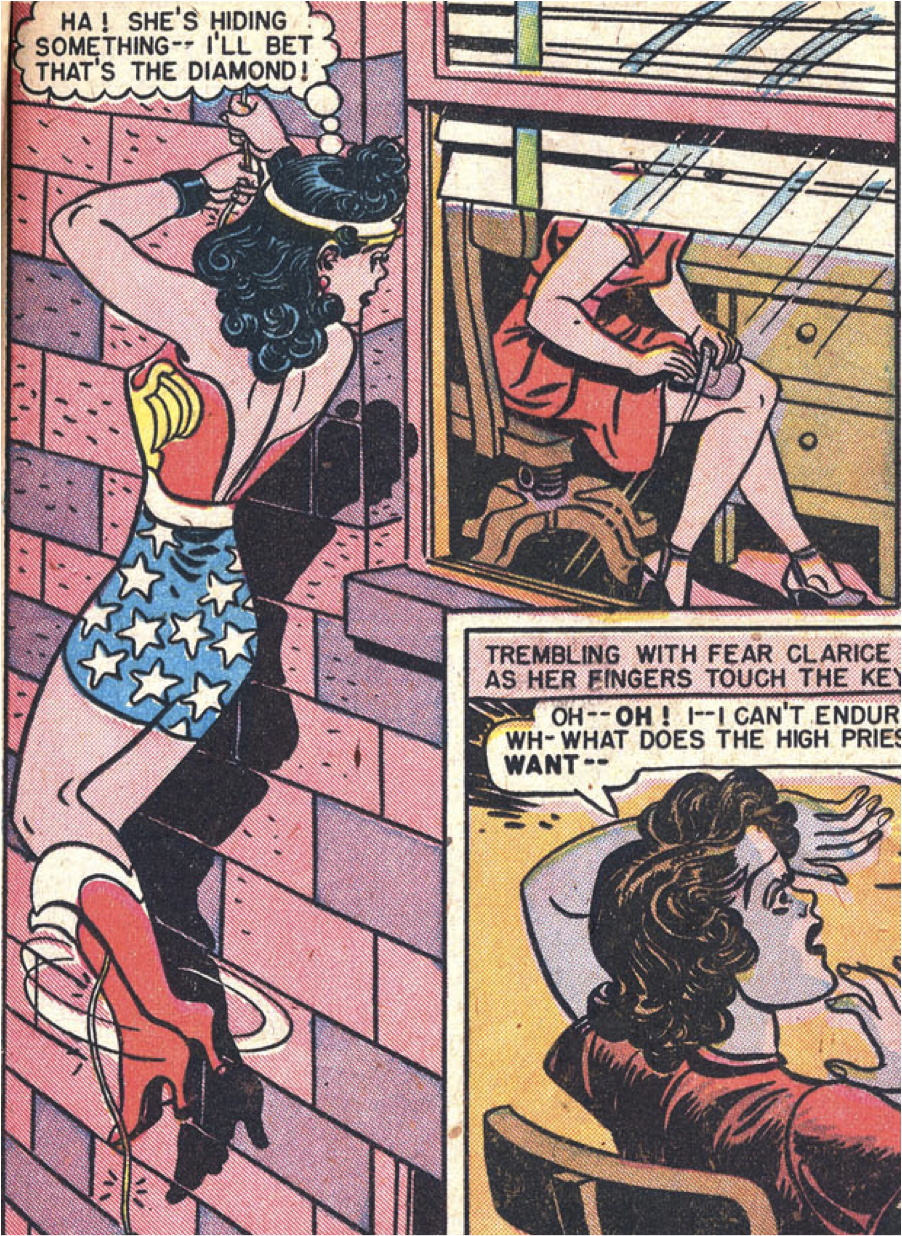

The battle between Wonder Woman and Villainy, Incorporated is a style war: patriotic primary colors versus a decadent, cosmopolitan spectrum; Roy Lichtenstein versus Picasso; Lego pieces versus burnt umber, melon, and periwinkle crayons. The more complex colors are often relegated to secondary characters and panel backgrounds, but precisely because of their outlandishness, they often end up coming to the fore. In this panel, for example, I find myself looking past Wonder Woman, at the bricks tinted pink and purple, at the gratuitously yellow-green strip on the window blinds, at the dab of purple on the spindle of the chair:

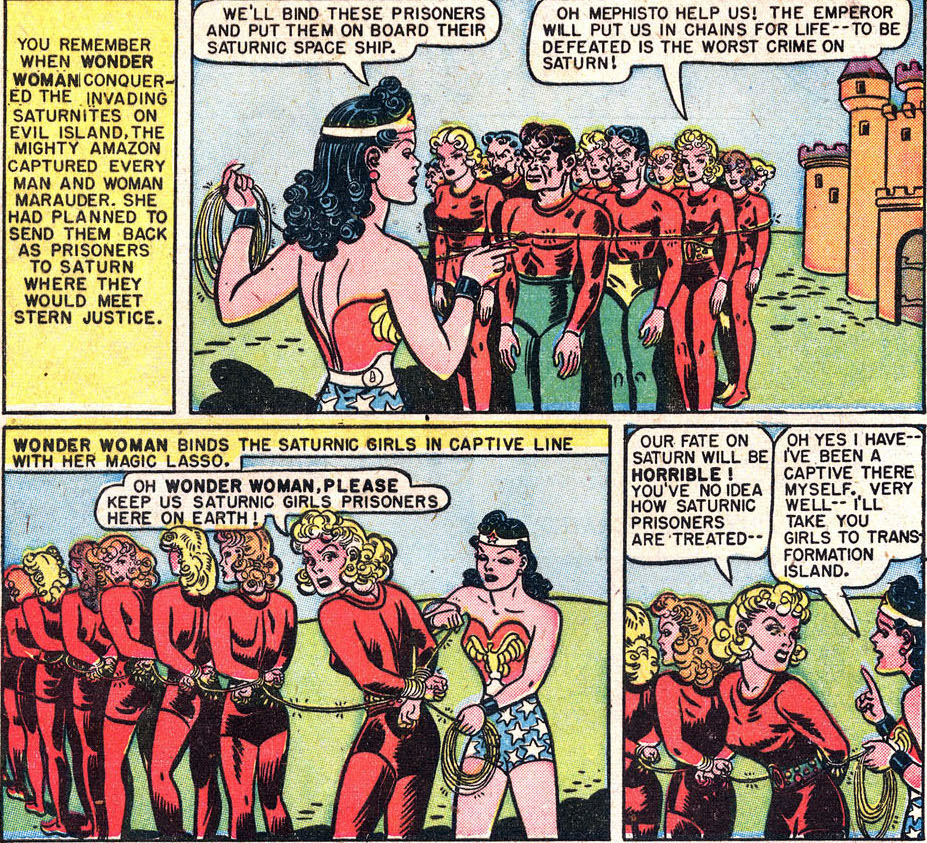

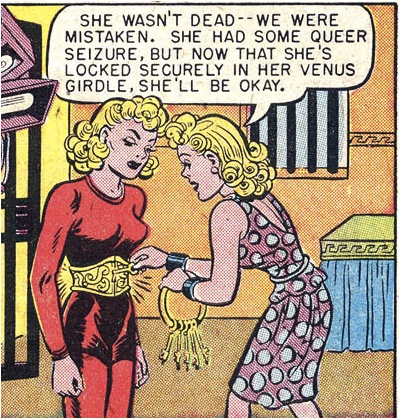

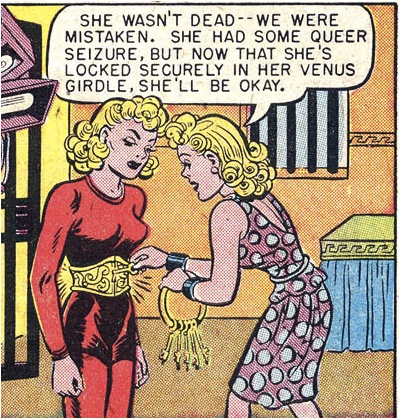

Wonder Woman’s costumes similarly pit the fascinations of villainy against the bland simplicity of the good guys. To be sure, Wonder Woman’s signature outfit is burlesque fetish wear — bustier, micro-mini, stiletto boots — but its eagle breastplate and white stars on blue background give an overall impression of wholesome Americana. Stripes are the only thing missing from this flag-like get-up, and are provided by the uniforms that the Amazons impose on their Saturnian prisoners, along with pacifying Venus girdles:

The prisoners on the right, who resist Eviless’s exhortation to resistance, speak as a united collective whose homogeneity echoes the striped pattern of their uniform; the whole ensemble embodies constricting, standardized repetition. Only a handful of prisoners, on the left above, resist the girdles. Once they’ve shed their prison garb, they pull sartorial focus:

Exchanging conformity for individuality, with stripes now removed from their persons and confined to the prison bars behind them, these figures, who make up Villainy, Incorporated, become a carnival of stripes and swirls, dots and spots, human and animal, butch and femme, West and East, pants and skirts, unitard and hoodie.

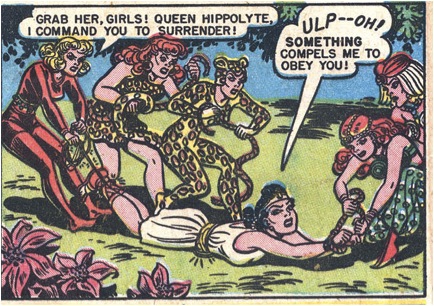

Why is Giganta in a wildcat pattern if she used to be a gorilla? Why is Cheetah sporting leopard spots? Why do those spots glow inexplicably green in the negative space between Eviless’s arm and breast? And look at the accessories — the bird headpiece, the sinister goggles, the orange scarf segmenting a red top and yellow pants, the elaborate cat ears, the fedora, the hood, the jewelry. At last, the circus has come to town. I could look at this panel for hours.

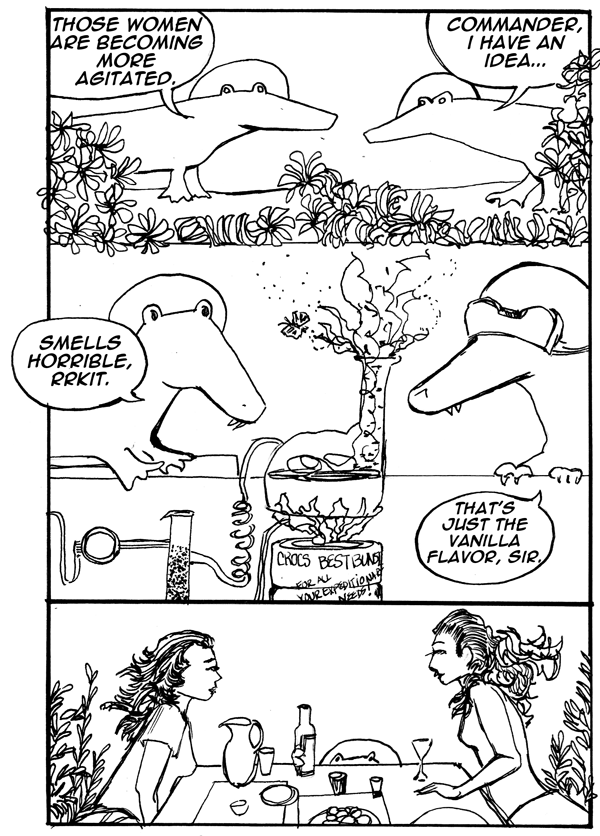

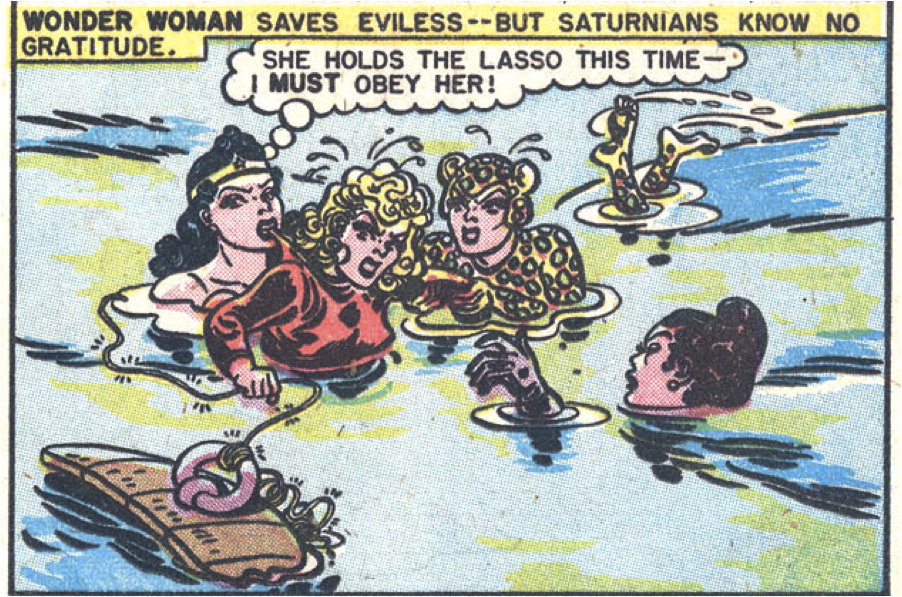

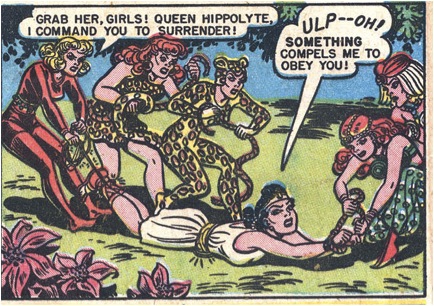

Losing oneself in one panel of a strip, or in the details of a single panel, especially in details of costume, is associated with fetishism, the fixation on a part detached from a whole. One way of describing my experience of “Villainy, Incorporated” is that I find it much easier to focus on individual panels and on details of individual panels than to follow the sequence of events, which feels more cyclical than progressive. If I force myself to focus, I see that we have eight villains, and that Wonder Woman first defeats four, then another two, and then the final duo. But tracking this is a chore, because in each of those mini-episodes, protagonist and antagonist keep switching roles: first the villains are bound to submit, then Wonder Woman, then the villains, then Wonder Woman. Often Wonder Woman finds herself having to obey the commands of an opponent who has snagged the heroine’s golden lasso, which allows anyone wielding it to compel obedience:

In this panel, I’m more interested in Cheetah’s feet than in what’s going to happen next. It’s hard to care about which particular character is wearing the Venus girdle or bound by the golden lasso at any given moment, because it’s clear that soon she will wriggle free and place it on someone else, who will in turn wriggle free and place it on her erstwhile captor.

Another way of putting this is that throughout “Villainy, Incorporated,” it’s hard to distinguish the tops from the bottoms, and sometimes even the good girls from the bad. Take Mala and Eviless, whose hairdos, like their names, are basically reflections of one another.

It’s as if the scene of sadism were more important to #28 than the story — as if sadism had itself become subject to the loopy visual tempo of the fetish. What matters most is not generating anxious suspense about what will happen next, but a feeling of secure suspension in a continuous series of images of women tying up women.

Wonder Woman thus seems to challenge the contrast between fetishism and sadism posited by Laura Mulvey in her classic essay on “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Mulvey sees Hollywood cinema as appealing to two types of pleasure that are of course related but look very different and appeal to different elements of our psyches. The first type is a fetishistic pleasure in isolated moments of female display that have no relation to linear plot progression. The second is a sadistic pleasure in narratives of pursuit, punishment, forgiveness, and control, in which men usually drive the action and women receive it. Mulvey sees both forms of visual pleasure as attempts to control castration anxiety, and people have been arguing productively with her schema for decades, which attests to both its insights and to its limitations. As Noah Berlatsky has pointed out in his readings of earlier numbers, the all-female universe of Wonder Woman undoes the identification of men with action and women with passivity and turns both the superheroine and the passive male into feminist fetishes.

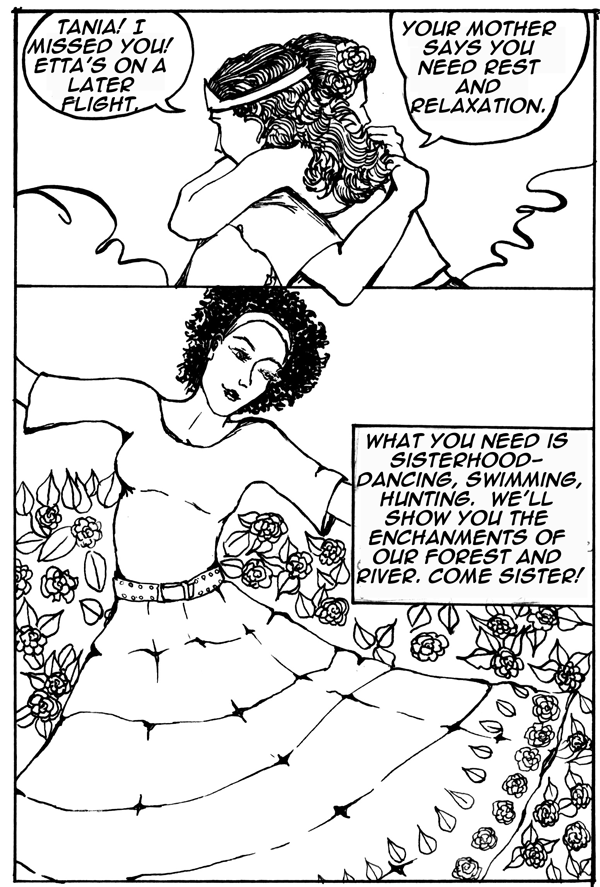

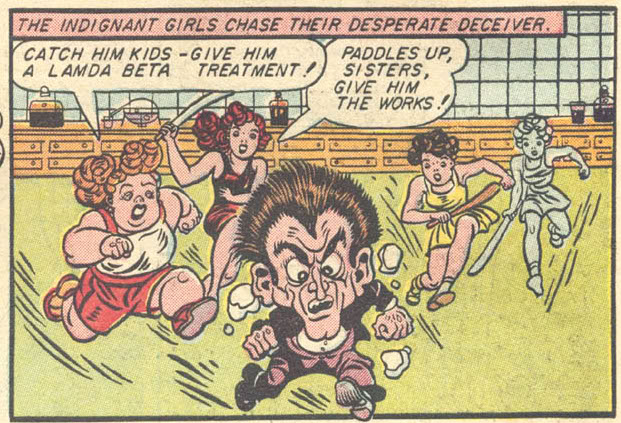

Mulvey assumes a specific kind of heterosexual framework that seems less than relevant to the lesbian kitsch world of “Villainy, Incorporated.” This is a universe of female prisons, Amazons swearing by “Suffering Sappho,”and boarding school crushes (“Oh what strength — Princess, you are wonderful!”). Is #28 just a variation on a girlie show, designed by men for men, an appropriation of lesbian pulp? Or does it allow both male and female readers to identify with powerful femininity and vulnerable masculinity? I’d incline to the latter, given how #28 pumps up female agency and bonds between women while downplaying male power. Steve is as apt to be tied up as any of the female characters, and in his last appearance in this episode, though he comes to Wonder Woman’s rescue, he’s rendered as a barely discernible stick figure.

Questions like the ones posed above are fun because they’re impossible to answer. I’ll end with another imponderable. Why don’t I find this egalitarian story line sexy, much as I enjoy the individual panels? Mulvey describes the “destruction of pleasure as a radical weapon,” and for me, #28 has indeed destroyed what Mulvey deems the sadistic pleasures of control and dominance associated with conventional linear narrative. To some, it may seem nonsensical of me to say that #28’s destroys sadistic narrative pleasure. The characters address one another as “slave” and “mistress” and there’s an image of a woman engaged in some kind of bondage on almost every page:

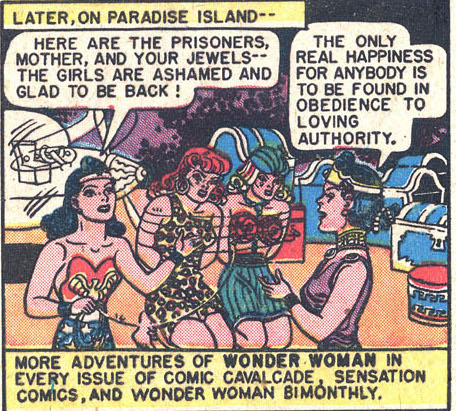

The BDSM imagery isn’t just an effect of the action-adventure plot; the Amazons speak frequently of their desire to compel “complete obedience to loving authority.”

Yet “Villainy, Incorporated” feels to me like it gently thwarts sadism, because while reading it, I find it difficult to sort out who is active and who is passive, who is subject and who is object. You’re dominant if you hold the lasso, submissive if it holds you. Even when captive, Wonder Woman performs feats of strength, like towing a submarine. The most obedient prisoners have also become so strong that by virtue of submitting to their captors they have acquired the power to rescue them:

Throughout #28, the captive guards and rebel prisoners trade places, producing the confusion of agent and object, person and thing, masculine and feminine, that Anne Cheng identifies with fetishism in her book Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface.

“Villainy, Incorporated” is obsessed with bondage scenes, but its version of BDSM is a reparative, maternalist one in which difference is dissolved, polarities blur, and rectilinear structure collapses. This relaxation of the more punitive energies that Mulvey links to classically constructed plots seems related to the shift in scene from the heterosexual one typical of Hollywood cinema to the female world of love and ritual that is Wonder Woman. It’s also related to the difference between feature films and comics; it’s as though episode #28 has internalized the seriality of the genre as a whole.

Perhaps “Villainy, Incorporated” frustrates my narrative pleasure because it often feels like it’s trying to reconcile sadism with moralism. In the name of Aphrodite, Wonder Woman practices a kind of radical Christian ethics:

The Amazons claim to be enforcing complete obedience for the good of their captives, with the aim of removing “all desire to do evil” from them. Like the nineteenth-century proponents of criminal rehabilitation analyzed by Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish, Wonder Woman prefers conversion to physical force, disciplining her enemies’ bodies in order to reform their souls. “‘I don’t feel cruel and wicked as I used to,'” exults Irene after doing time in a Venus girdle. But isn’t moral reform the ultimate invasion? What’s left of a person if she lacks even the desire to do evil? Is the problem with Wonder Woman that she is too sadistic, rather than not sadistic enough?

Or perhaps I have a lukewarm response to Wonder Woman because she dares to expose the soft underbelly that sadistic scenarios aim to protect. Explaining this requires a long detour through feminist psychoanalytic theory. Practitioners of BDSM often describe the core of their sexuality as an ethic of radical care that undoes any strict separation of omnipotence from helplessness. But many people see BDSM scenarios as appealing precisely because they revolve around polarized roles.

Jessica Benjamin has written brilliantly about sadistic fantasies and representations in The Bonds of Love and an essay in Like Subjects, Love Objects. I can’t do justice to her subtle argument here, but here’s the comic-book version of the points I find most relevant to Wonder Woman and its variations on the theme of bondage and submission between women.

For Benjamin, fantasies of erotic domination revolve around splitting. As infants, we feel omnipotent and helpless, destructive and vulnerable. Indeed, our very feelings of omnipotence make us feel helpless, anxious that our own aggression might destroy the external world on which we depend for survival. We find it almost impossible to discern the difference between what is inside us and what is outside us. We also find it almost impossible to discern the difference between the external world in general and our parents in particular, and like most psychoanalysts, Benjamin sees mothers as the prime embodiments of both the external world and parental care.

Engaging with various thinkers, including Donald Winnicott (a key figure in Alison Bechdel’s new graphic memoir, Are You My Mother?), Benjamin sees fantasies of power and submission as resisting erotic intersubjectivity, in which each recognizes the other as “a being outside omnipotent control” (186). Sadistic fantasies manage the universal infantile experience of feeling overwhelmed by both one’s own omnipotence and one’s mothers. They appease “the conflict between recognition and destruction of the other” (183) by creating a strict demarcation between fixed poles of power and submission. Benjamin writes that these are usually “organized by gender,” with men dominating and women submitting. This suggests lack of familiarity with the diverse range of BDSM scenarios in circulation for at least the last two hundred years, but gender is not really the point of her argument.

Benjamin’s key point is that s-m scenarios and erotic intersubjectivity alike are grappling with the same psychic challenge: how to reconcile tensions between sameness and difference, merger and separation, closeness and distance, acceptance and rejection, idealization and recognition. Sadistic fantasies may seem like expressions of cruelty, but in her view they are also working out the fear that the maternal object could not survive one’s aggression (196). In sadistic and masochistic fantasies, “each can play only one side at a time.” Benjamin contrasts this to erotic experiences in which those involved are neither perfectly strong nor perfectly weak. Those experiences emerge most readily when one has been able to recognize the mother as an independent subject, which helps one develop an erotic self that can play with destruction without being extinguished by it (206). Benjamin clearly prefers Eros to sadistic fantasy, but she’s not censorious of fantasy; she sees pornography as a sign of suffering mainly insofar as many people report feeling bad about their responses to it.

Where does this leave Wonder Woman? Benjamin describes sadistic fantasies as a way to cope with the sensation of “encapsulation in omnipotence,” which is an interesting gloss on being bound by a golden lasso and a Venus girdle that compel complete obedience.

I don’t think we need Jessica Benjamin to tell us that Wonder Woman #28 is obsessed with bondage. What Benjamin’s framework helps us see is that Wonder Woman revolves around what we might call maternalist bondage. Certainly, in this comic, you’re either tied up or doing the tying, and each can only play one side at a time. But characters switch from one side to another with such frequency and rapidity that they’re almost occupying both sides at once, yielding oxymoronic beings such as “captive guards” and Amazons bound by their own lassos.

The tender solicitousness Wonder Woman so often expresses for those she’s restraining (“What’s the matter, Eviless?”) makes Amazonian domination a relatively explicit expression of the need to give and receive comfort and recognition (“I hate to pull Eviless under water”). For Benjamin, sadistic fantasies exist to neutralize, even repress, such needs at their most intense and naked. Wonder Woman dares to go where most s-m fantasies don’t — into the turbulent emotional core of neediness and reparation that most sadistic scenarios tie up into neat, well-defined packages. And the vertiginous switch-hitting that results disrupts the controlled progression of plot along with the polarized distribution of power.

Wonder Woman #28 doesn’t give us perfect reciprocity; this is a classic comic, after all, and it’s inconceivable that its blissfully one-dimensional characters would lend themselves to the intersubjective encounters with difference to which erotic reciprocity gives rise.

What Wonder Woman #28 does give us is an obsessive depiction of the reversibility and replication of power between women. That reversible reciprocity is embodied in Wonder Woman’s name. WW: these initials constitute a double mirror image, since the first letter is the same as the second, and each letter consists of twin V’s. The two V’s that make up each W recur in the peaks of Wonder Woman’s boots. We have regular V’s in the back:

and inverted ones at the front:

WW is also MM upside down — just as adoration is the flip side of rage, omnipotence is the flip side of helplessness, and Wonder Woman is the flip side of Mom. But then, what isn’t?

__________________________

This is part of a roundtable on the last Marston/Peter Wonder Woman. The roundtable index is here.