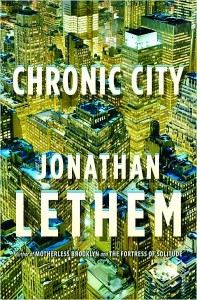

In part one I discussed how the existence of the internet complicates and modifies many of the ideas laid out in David Foster Wallace’s “E Unibas Pluram and in particular how our transition from a nation where human labor is engaged in making objects to one in which it is engaged in making images is a key societal change that a recent crop of novelists are trying to address. Today, I’ll talk at length about Jonathan Lethem’s recent novel Chronic City as an example of this.

____________________

It’s hard to summarize or even introduce the plot of Chronic City, as its gradual unfolding and the realizations that come with it is an important part of the experience of a first reading, but as Hooded Utilitarian is a pro-spoiler kind of place, let’s give it a shot. Chronic City concerns the (mis)adventures of a washed-up former child star named Chase Insteadman who enjoys a mid-thirties second celebrity due to his engagement to a doomed astronaut named Janice Turnbull. Janice is stranded in a space station behind a line of Chinese mines, a series of letters she writes to Chase her only communication with the Earth (or the reader). Chase meets and befriends a washed-up cultural critic named Perkus Tooth, who is one of contemporary literature’s great eccentric side-kicks. Perkus, who made his reputation posting hand-scrawled broadsides on the walls of buildings all over New York, now lives in a rent-controlled Upper East Side apartment where he does lots of drugs, eats cheeseburgers and muses about the hidden connections between various pop culture ephemera.

It’s hard to summarize or even introduce the plot of Chronic City, as its gradual unfolding and the realizations that come with it is an important part of the experience of a first reading, but as Hooded Utilitarian is a pro-spoiler kind of place, let’s give it a shot. Chronic City concerns the (mis)adventures of a washed-up former child star named Chase Insteadman who enjoys a mid-thirties second celebrity due to his engagement to a doomed astronaut named Janice Turnbull. Janice is stranded in a space station behind a line of Chinese mines, a series of letters she writes to Chase her only communication with the Earth (or the reader). Chase meets and befriends a washed-up cultural critic named Perkus Tooth, who is one of contemporary literature’s great eccentric side-kicks. Perkus, who made his reputation posting hand-scrawled broadsides on the walls of buildings all over New York, now lives in a rent-controlled Upper East Side apartment where he does lots of drugs, eats cheeseburgers and muses about the hidden connections between various pop culture ephemera.

Perkus and Chase’s crew is rounded out by two other friends: Richard Abneg and Oona Lazlow. Abneg, a former tenant-rights radical, now works for New York’s billionaire mayor undoing rent stabilization laws. Oona, Perkus’s former protégé with whom Chase begins an affair, ghost-writes celebrity autobiographies. Together, they discover and begin chasing after quasi-mystical objects called chaldrons, odd sparkling urn-like containers that they’ve only glimpsed images of on Ebay.

The novel moves with the episodic rhythms of a difficult friendship. There are bursts of and gestures towards an overriding narrative involving a conspiracy that remains thoroughly in the background until the final few chapters. In its place, are many many conversations about pop cultural artifacts, soirees amongst the elites of Manhattan and ongoing searches for capital-t Truth.

Wallace talks about us being one big audience, but Chronic City is after something a little bit different. Through Chase’s eyes, what we see is an age where we are spectators and consumers, yes, but we’re also performers. We’re also the ones making the very culture we’re the audience for. Via YouTube, Facebook, Blogs, Tumblrs, Twitter, Pinterest, through Vimeo and Etsy and Soundcloud and countless other outlets, we are audience and performer at the same time. We can no longer claim—as Wallace does— that a culture is being imposed on us, one that’s simultaneously delightful and infantilizing and isolating. We are both halves of the equation now. Whatever happens, we are complicit in it.

Complicity is the big wrinkle that Chronic City brings to this issue. And it turns out that once you start looking for it, the word complicit appears all over the book[1]. The word first surfaces on page 13 when Chase is trying to explain his newfound friend Perkus to the reader, when, after a litany of different cultural subjects Perkus would rant about, Chase sums it up thusly:

In short, some human freedom had been leveraged from view at the level of consciousness itself. Liberty had been narrowed, winnowed, amnesiacked. Perkus Tooth used the word without explaining—by it he meant something like the Mafia itself would do, a whack, a rubout. Everything that mattered most was a victim in this perceptual murder plot. Further: always to blame was everyone: when rounding up the suspects, begin with yourself. Complicity, including his own, was Perkus Tooth’s only doubtless conviction. (emphasis mine)

The tone here is not moralistic. Chronic City is not saying—and never says— that we are evil for our participation. If anything, it views this participation that we all do (including Perkus, including Jonathan Lethem, including me, including you) as a fact. The book may be trying to make us see this participation, but it’s not scolding us for it. Instead of judging us as Perkus does, Lethem tries to make us aware of the ways that we all make our bargains, have our scripts and have to pay a price for being in and enjoying this society we’ve made.

And we do enjoy it. Let’s not bullshit each other. Like Richard Abneg screaming that he wants to fuck a Chaldron the first time he sees one, there’s something very ecstatic about all of this. It’s not without joy. But it’s not without its price either, particularly for us artistically-inclined folk. The internet has both devalued creativity and enabled it. There’s more writing—and reading—going on than at any point in human history, and much of it is for free. Facebook is able to have a small staff because its users make its content for them.

That content is worth pausing to consider. I find it striking, for example, that the first major internet meme most people I know encountered involved baby talk gibberish scrawled on pictures of kittens, and much of the writing we generate is poisoned with reflexive bad-faith and a kind of unquashable rage. And there’s a constant feedback loop of participation, anger and trollery begetting anger and trollery like the two warring factions in The Butter Battle Book.

I’m complicit right now, come to think of it. I am writing this post for free on the internet. Generating more content, some of it fueled with internet skepticism, a skepticism that is immediately defanged because you have to get onto the internet to read it in the first place. Indeed, I don’t watch DFW’s six hours of television a day, but I spent a great deal more time than that staring into my computer screen, interacting with people online, passing along memes and hashtags, doing a lot of things that feel like work but aren’t, participating in this culture I also try to critique. What choice do I, do any of us, have?

Chronic City is examining this world built on complicity, built on active—if often unwitting—participation in the very systems that we are angry at and want to overthrow. And it examines that world through the very specific—and very odd—eyes and words of narrator and protagonist Chase Insteadman.

Chase is a retired act-or. He no longer acts. That’s the key aspect of his character. Within the book there are only a handful of moments when Chase consciously commits some kind of action in pursuit of an objective (or, in other words, acts the way we expect a protagonist to act). Instead of being an actor, Chase is imbued with a kind of monstrous self-awareness. He might be blind to the realities of his life, but he knows he’s blind. One of the great pleasures of the book is reading Chase talking about himself, which he does with some regularity. Pay particular attention to the way he phrases the following on 63 and 64:

The only role I ever played to anyone’s complete satisfaction was Warren, on Martyr & Pesty… The show itself was avowedly “dumb” and we all (writers and actors, network, critics, audience) flogged ourselves those days for our complicity in its runaway success, but I, the exception was unaccountably “soulful.”… I no longer act, that is unless you’d call my every waking moment a kind of performance.

Or this on 66-67:

I’m outstanding only in my essential politeness. Exhausting, this compulsion to oblige any detected social need. I don’t mean only to myself; it’s frequently obvious that my charm exhausts and bewilders others, even as they depend upon it to mortar crevices in the social façade…. But if beneath charm lies exhaustion, beneath exhaustion lies a certain rage. I detect a wrongness everywhere. Within and Without, to quote a lyric. It would be misleading to say I’m screaming inside, for if I was I’d soon enough find a way to scream aloud. Rather, the politeness infests a layer between me and myself, the name of the wrongness going not only unexpressed but unknown. Intuited only. Forbidden perhaps.

It is a very curious thing for a protagonist to be someone who doesn’t act. Doubly curious when that person is also the narrator. We are used to our protagonists wanting things and then taking certain actions to get them. But other than sex with Oona, we know very little about what Chase wants. Chase has little inner life, and is open about this. To drive the point home, Insteadman’s apartment is basically empty, devoid of any belongings worth describing. Instead, what he wants to describe to the reader is the view outside of his window, a view being slowly eclipsed by a high rise going up in front of it.

Chase’s mix of self-awareness and blindness, politeness and rage results from his transformation prior to the book’s beginning from a subject into an object. He understands that his existence is predicated on being used by other people. His life is lived as an extra man at a series of high-society functions; his politeness, sit-com childhood and newfound fame as the fiancée of a doomed astronaut get him invited to various soirees where he sings for his supper by discussing his love of his lost Janice Trumbull, whom he cannot even remember anymore.

Via Chase, Chronic City shows how we are losing pieces of our subjectivity in all our constant performing for other people; we are instead becoming—and treating others as—objects. As our culture moves from making things to making images of things—a subject Chronic City turns to overtly in the second half of the book—we in turn objectify ourselves. Chase talks about this frequently. As he goes to a fancy dinner with the richest couple in New York, he remarks that his “presence for an evening, or at least the duration of an elegant dinner, had been auctioned off as a premium, at a benefit for one of Maud Woodrow’s charities. I couldn’t anymore recall which.” Six pages later, he says that his face is a mask. Chase has turned himself into an object to be sold by one person to another and he can’t even remember for what cause he’s doing it. Is it any wonder that, in the midst of the dinner, he comes down with a crippling flu?

I also don’t think that it’s a coincidence or authorial oversight that both Chase and Richard Abneg treat the women in their lives as objects. We know Oona has large incisors, heavy glasses, a black bob haircut, that she’s very skinny and that she has peach sized, impertinent breasts. We don’t know who her parents are or where she comes from. We don’t know what she desires. Chase says he loves her, but his love largely boils down to trying to investigate her, to solve the problem of who she is against her own will[2]. Abneg, meanwhile, gazes upon the sleeping form of his lover Georgina Hawkmanaji and intones to his friends, “Such an amazing shape. How can anyone ever sit in a meeting, or make a plan, or add up a column of fucking numbers, when there’s a shape like that somewhere out there, a shape like that with your name on it, coming to get you?” The Hawkman, as she is called in the book, is a shape rather than a person.

The novel situates these people, these shapes, these performers in a very particular environment, for the Manhattan of Chronic City (and I hate to spoil this, but the book is undiscussable without this knowledge) is not our New York. It’s an alternate one, a kind of Earth-2, one where instead of 9/11 a great, never-ending fog descended on lower Manhattan, one where film directors Morrison Groom and Florian Ib have directed movies starring The Gnuppets and Marlon Brando or where people listen to groundbreaking post-punk band Cthonic Youth.

There’s a heavy emphasis within the novel on spaces-within-spaces. Chase meets Richard at a party that takes place in a Brownstone within an Apartment building. A restaurant might hide a secret room. Perkus’s apartment, like a TARDIS is “a container bigger on the inside than the outside.” An installation artist named Laird Noteless’s signature artworks involve huge chasms dug into cities.

Children’s stories often begin with a kind of familiar cadence. Once there was the Land Of _______ and in the Land there was a forest, and in the forest there was a house and in the house there was a room and in the room there was a cabinet and in the cabinet there was a drawer and in the drawer there was a box and in the box there was a….

What’s delightful about this for children (and adults) is that you are waiting to get to this end of the chain, because at the end of the chain is what really matters. It’s the magic ring. Or the truth. But on the internet, when you follow the series of boxes within boxes, you always hit another link in the chain, another rabbit hole to go down. You are always going deeper and deeper into new boxes and the truth, if it exists, becomes destabilized. After all, in a world in which editing a Wikipedia article can change Marlon Brando from dead to alive, who knows what’s real and what’s fake? Chronic City takes this idea and spins a world of it. Its central trio of men—the brain, the body and the raging erection of Perkus Tooth, Charse Insteadman and Richard Abneg—seem to be on a search for truth. But the truths they eventually discover—I’ll leave them unarticulated here— might not even be true, and might not be actionable even if they are.

This all comes to a head once chaldrons show up and Perkus, Chase and Richard begin a series of mad scrambles to get their hands on one. Their first attempt leads to one of the book’s great setpieces, a mad Ebay-and-borrowed-credit-card pursuit fueled by high grade marijuana and the improvised guitar stylings of Sandy Bull (who, it turns out, actually exists). It takes quite awhile for the trio to figure out why they even want a chaldron so badly in the first place. It’s a perfect locus of desire… but a desire for what?:

“For something so warm… it casts a sort of … brusque… watery…. Shadow… over so much else… that I took for granted…”

“Despite sounding like a retarded Wallace Stevens I actually get you,” said Richard. “That thing’s the ultimate bullshit detector–“

“Sure, and what it detects is that your city’s a sucker[3], Abneg.” Perkus spoke with a startling insistence, but his tone wasn’t needling. “Your city’s a fake, a bad dream.” This was somehow the case, the chaldron interrogated Manhattan, made it seem an enactment. An object, the chaldrone testified to zones, realms, elsewhere. Likely we’d lost the auction because one couldn’t’ be imported here, to this debauched and insupportable city. The winners had been rescuing the chaldron, ferrying it back to the better place.

And so we return back to Perkus’s essential truth: that somehow a fast one has been pulled on the world by the world, leaching everything real out of the universe and, to coin a verb, ersatzing it. Perkus responds to this perceived conspiracy in two seemingly contradictory ways. He both attempts to reject the world that he views as corrupt and looks for vibrational evidence for his one truth in pop cultural ephemera. In this, Marlon Brando serves as Perkus’ Space-Coyote-Spirit-Guide, a human signpost revealing hidden truths. Or rather, the same truth, over and over again.

Whether or not the secret Perkus has uncovered is, in fact, true is an open question within the novel. Chronic City is suffused with contradictory moments, ambiguous clues, impossible moments. The reality of the novel—like the reality of Wikipedia— is too unstable to permit anything like an objective truth. As a result, the book avoids the kind of modernist and romantic clichés about outsider artists. All of Perkus’s ideas could just be a bulwark against his sense of failure, a way for him to sabotage any chance at a recognition he claims to not want but also craves[4].

The tone of the novel, as mentioned before, eschews judgment for a satirical, wise-cracking humor that covers over—and eventually gives way to—despair. For when you are trapped in a world where all is image, and those images may not even have real-world referents anymore, when the closest to freedom you can come is to realize you are a puppet, where hidden conspiracies are ever-present yet might simply be nothing more than the tacit acceptance and perpetuation of the world as it is, it’s hard not to despair.

Chronic City isn’t the only recent work to take this state of affairs as subject matter. Jennifer Egan’s Look At Me, the recent film Shame, Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore, Dan Chaon’s Await Your Reply, even Dash Shaw’s recent Bodyworld are all suffused with information-age anxieties about identity, reality, and image. Obviously, these themes are not new—they’re present in work as diverse as Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and much of Philip K. Dick as well as the Image-Fictioneers that Wallace celebrates— but in this new crop of information age literature we see these themes and anxieties jumbled and replayed in new ways. If previously we were concerned with loneliness, now we’re concerned with a kind of alienating hyper-sociality. If before we wanted to penetrate surfaces to get at the realities underneath, now we’re worried there might not be any reality to get to. If before we were victims of a system imposed upon us, now we are creators and perpetuators of that very system.

Of course, maybe it’s always been thus. Perhaps it’s just more visible now. After all, Perkus can’t point to the time when we got amnesiacked. It exists outside of consciousness, fueled by the endless money of the inescapable Manhattan, a world rendered so insular in the book that the reader is likely to wonder along with Chase if the rest of the world even exists. Of course, it does and it doesn’t. As Fozzy says in this clip, uttering the essential truth of his Gnuppet brethren, I do understand that I am not a real bear. But I know what I am… I’m a real puppet.

[1] Not for nothing, as well, are two of the four main characters sell-outs. Abneg has sold out his political beliefs and Oona has sold out her talents. Yet, and it’s a testament to the book’s charms, they remain loveable to us.

[2] There’s another essay to be written about how Oona is in many ways a response to all of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl/ Mysterious Woman Shaman clichés of early 21st century literature and film, particularly in her refusal to indulge or take care of Chase at his most immature and vulnerable moments. That’s for someone else to write.

[3] It’s not really germane, but this is one of the book’s many references to LCD Soundsystem, which joins a whole host of things that Lethem references with pithy one-liners.

[4] Perkus, we learn, turned down a book deal once because the book was going to be marketed as rock criticism and he hates rock critics.