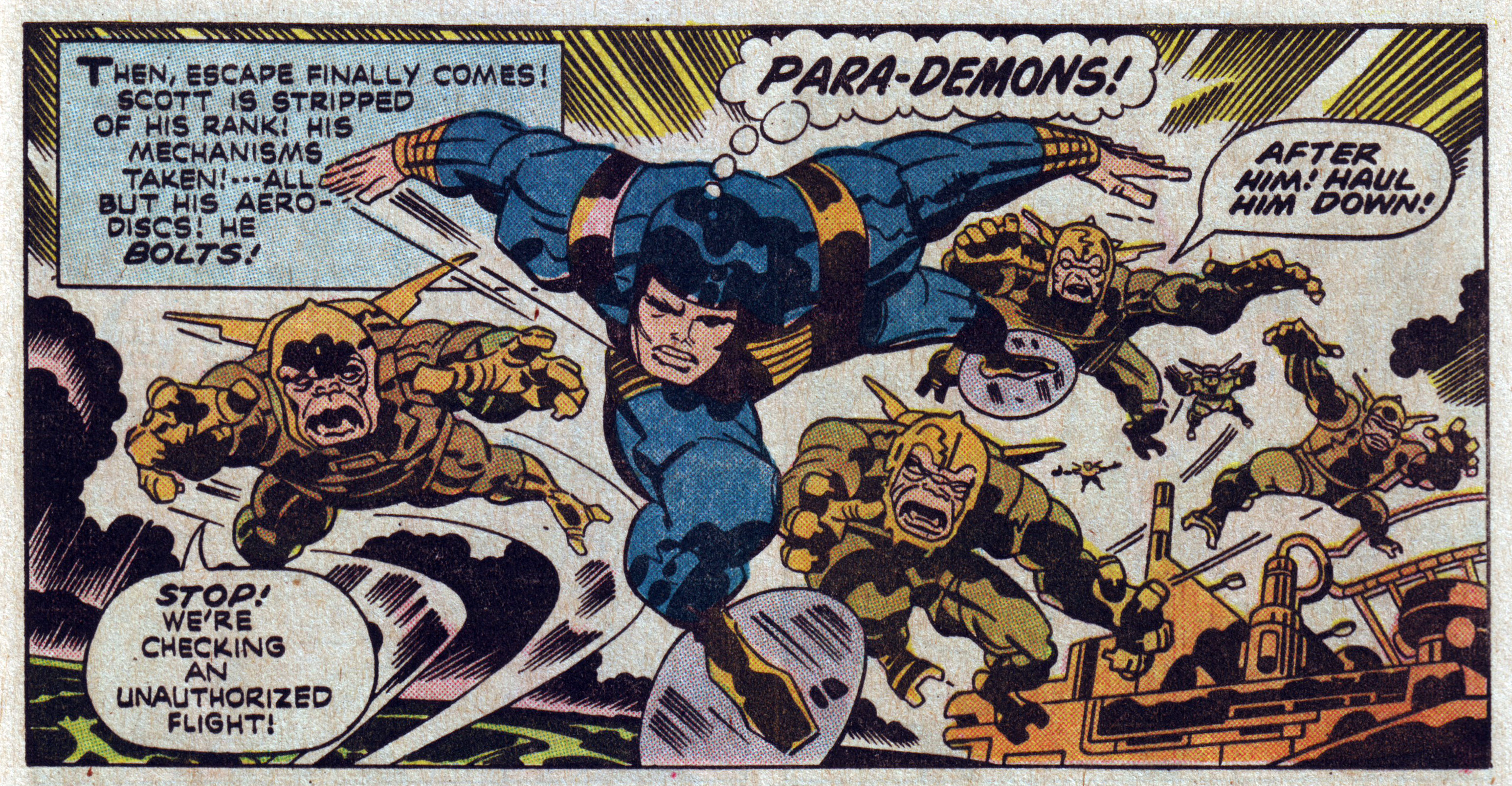

Of late, much of comicdom has been abuzz with the sale of the original art for the cover to Amazing Spider-Man #328 (by Todd McFarlane) for $657,250. Of this, I shall say very little. Suffice to say that the same auction house will be offering a small but similarly sized painting by Pierre-Auguste Renoir in November with a high estimate of $700,000. One presumes that this painting will sell for slightly more even if it isn’t the finest work in Renoir’s oeuvre.

Proceeding much more quietly over the last few months has been the gradual disposal of one of the finest collections of Gasoline Alley dailies in existence. The collection is not notable so much for its size (which while large, only numbers in the 100s at last count) but for the absolute significance of what they depict, their vintage, and their aesthetic merit. The auction house handling the sale has stated that all the art comes from the “Estate of Frank King”.

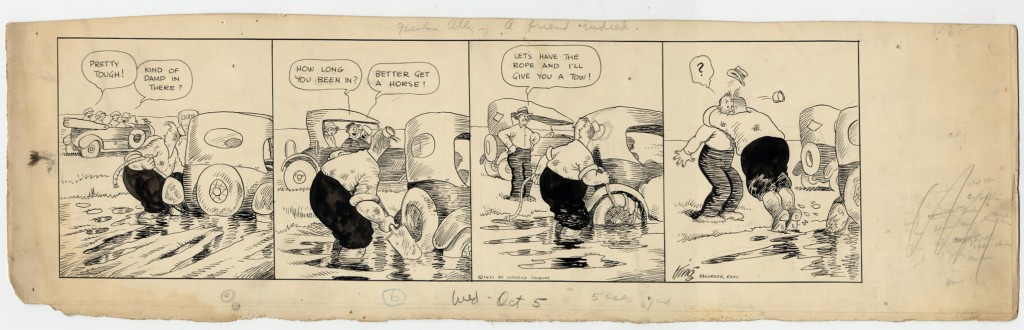

King’s skillful, light ink drawings can be found on modestly sized (about 6″ by 21″) sheets of aging paper with traces of stains and browning. The paper itself seems roughly cut from larger sheets and is frequently in excess of the requirements of the art. King gave individual titles to each daily, often writing these concise commentaries in cursive pencils at the top or sides of the finished art. Their importance relates to King’s working methods and his intentions. For obvious reasons, these titles aren’t reproduced in the recent Drawn and Quarterly reprints though the original art would have contributed greatly to the quality of that reprinting. The smeared countenance (in the reprint) of the “first Skeezix” strip of 14th February 1921, for example, would also be pleasantly rectified by the original art to that daily (which is soon to be offered at auction).

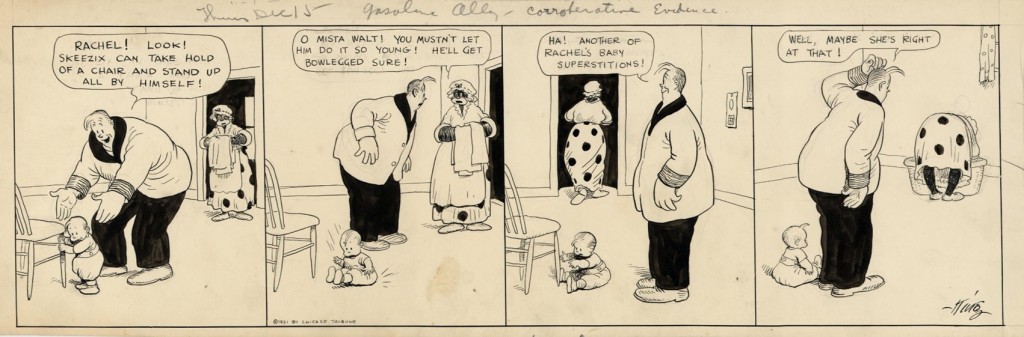

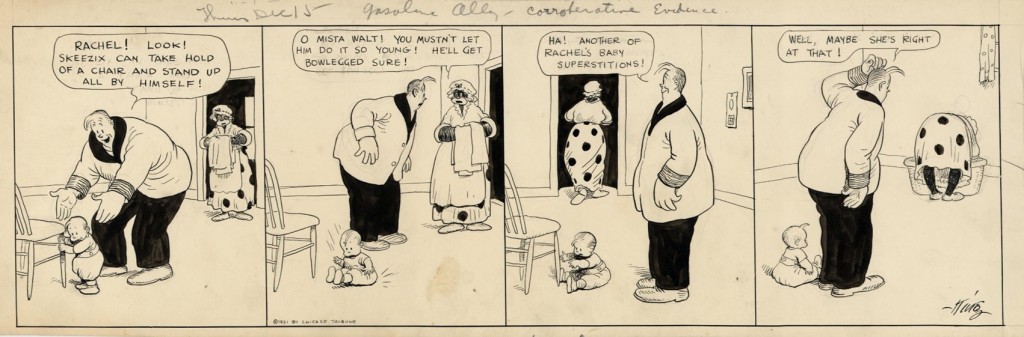

The more I look at Gasoline Alley, the more it seems to me that it is the kind of strip which is best appreciated the way it was originally intended—as a daily serial—and not read at length in the book collections which are undoubtedly welcome from an archival perspective. The passage of time is critical to the reader’s engagement with the strip. This can be easily appreciated if one considers that dailies acquired by a Gasoline Alley devotee like the collector C. E. in which we see Skeezix’s developmental milestones—from sitting (22nd September 1921) to standing (15th December 1921)—and his fateful meeting with his dog, Pal.

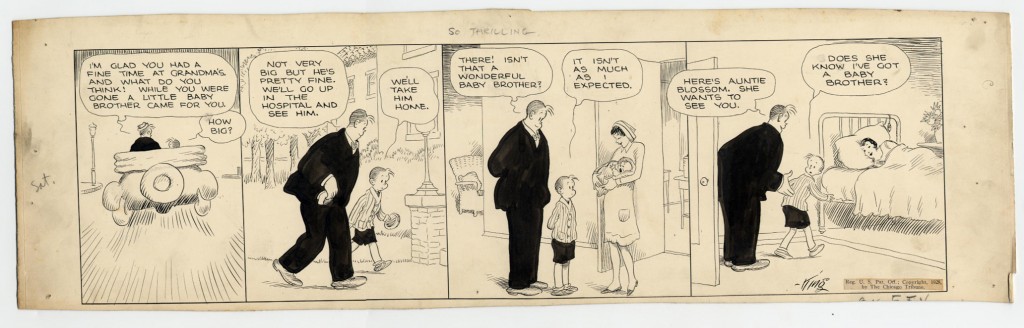

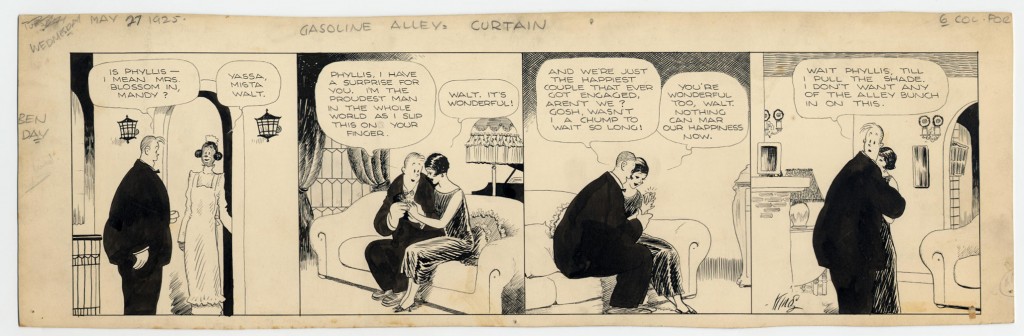

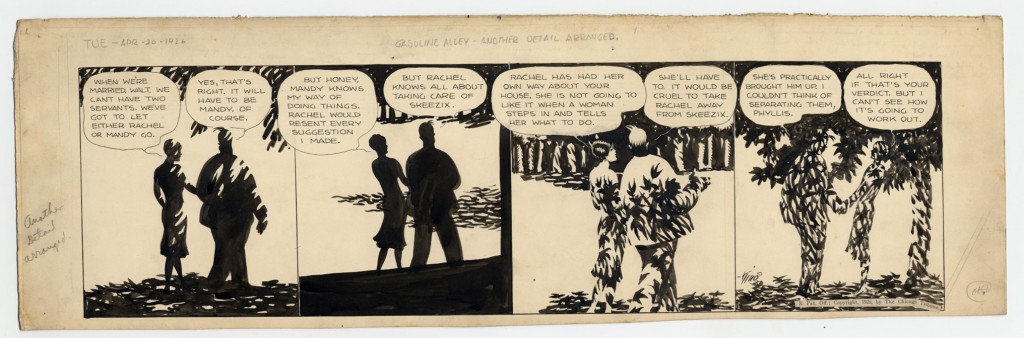

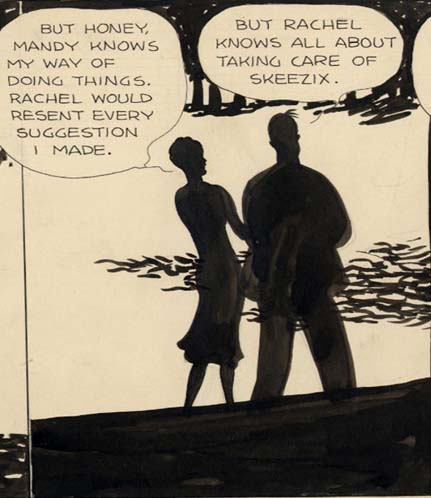

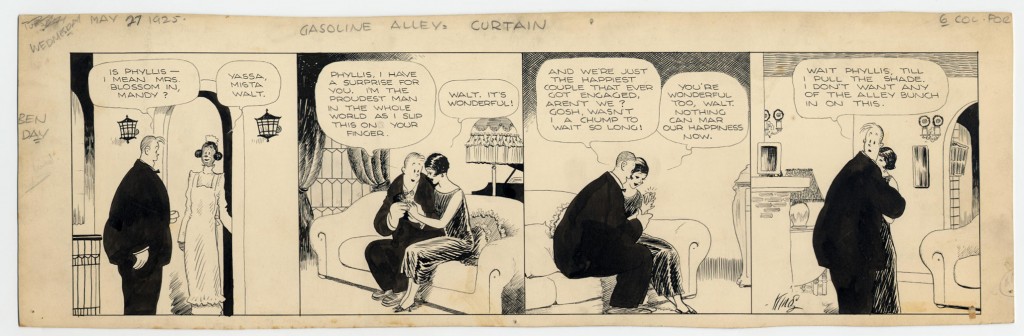

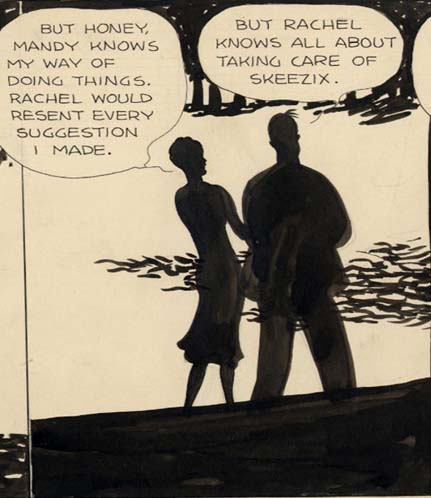

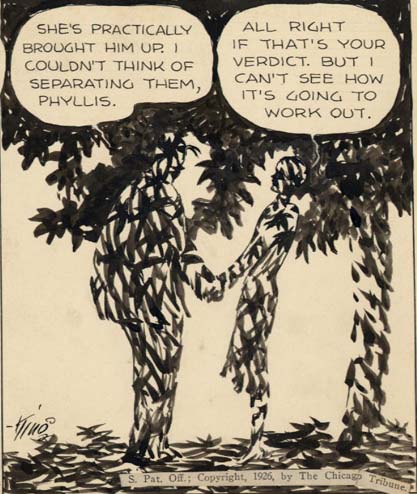

And if we treasure that moment when Walt finally gets engaged to Phyllis Blossom (the matriarch of a long line of Gasoline Alley characters)…

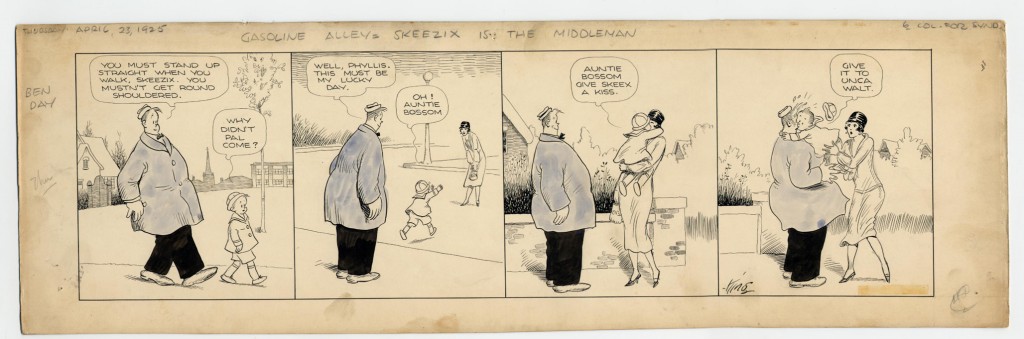

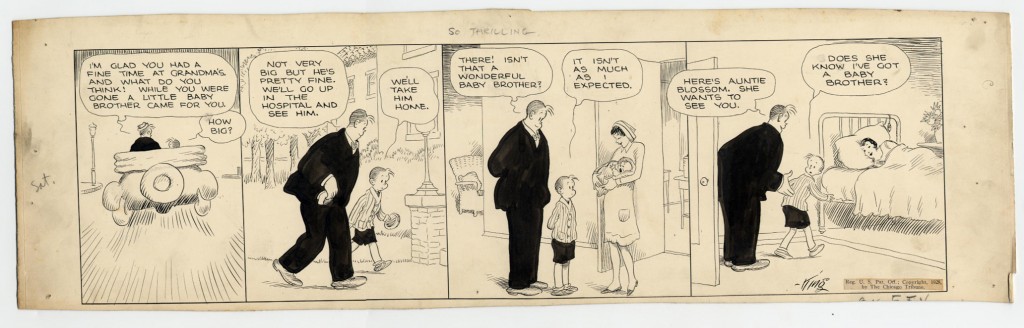

[Skeezix meets his brother for the first time.]

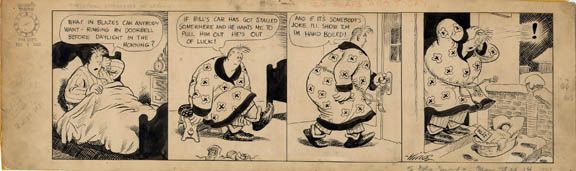

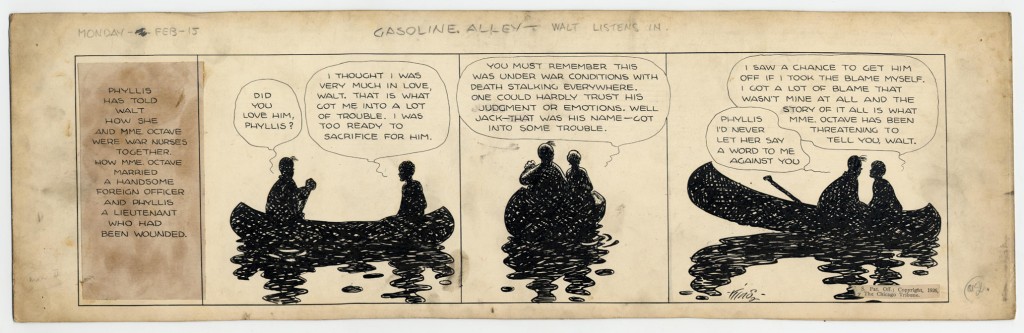

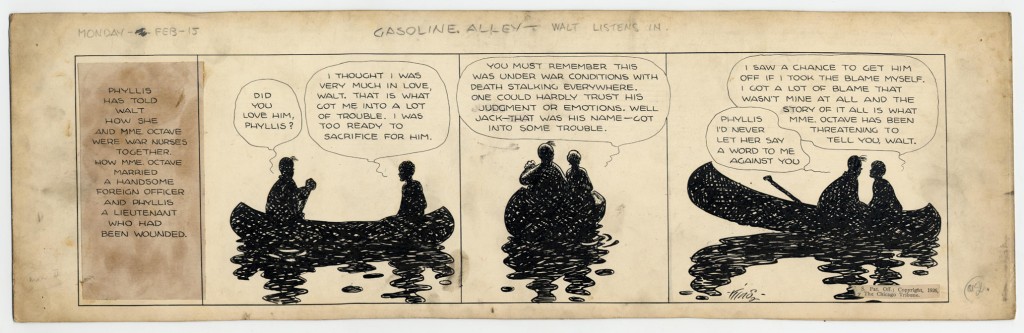

…it is only because of the couple’s long and chronologically drawn out process of courting, and the nefarious schemes instigated to pull the couple apart. The scenes of dark foreboding…

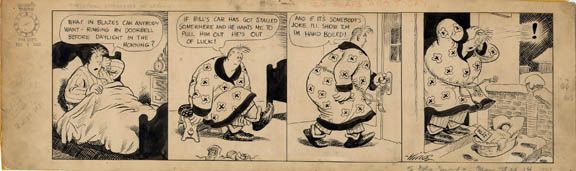

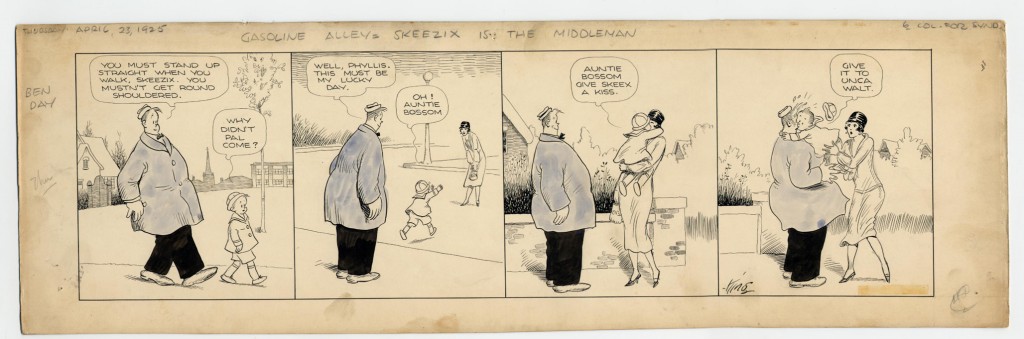

…contrasting with the almost saccharine, though not wholly preposterous, moments of cuteness.

While we may chuckle at these gentle scenes from another age of romanticism and worldly denial, King’s attention to detail is still striking. In the third panel of the daily above, Phyllis Blossom’s eye is subtly curved into an inverted U denoting delight and in the scene below where she is given her engagement ring, she suspiciously casts an eye out at the reader in the fourth and final panel.

***

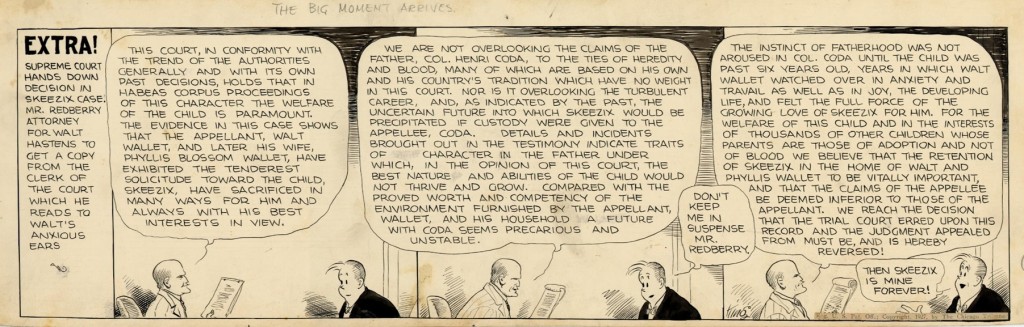

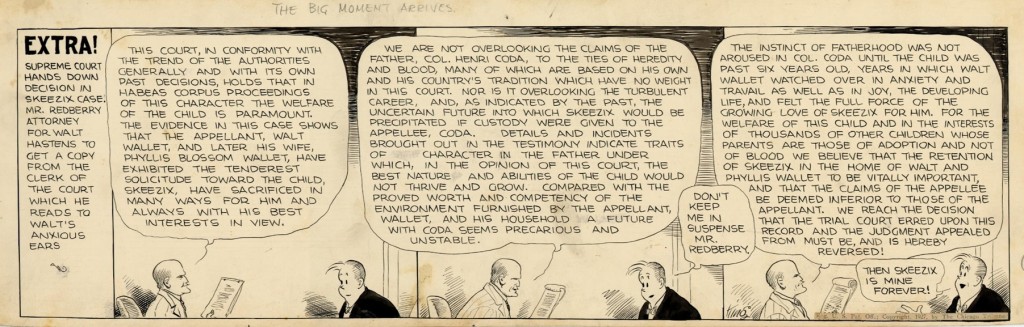

I should add at this point that the acquisition of any fine collection of art has less to do with taste than with other factors. Far more important in the case of comics, is availability followed by price and financial ability. Only then does the collector face the question of taste. As far as Gasoline Alley is concerned, the choice (in the face of moderate financial impediments) lies between historical significance and aesthetic quality. No doubt the two often coincide in King’s famous strip but there are a number of instances where they don’t. There is nothing especially beautiful about the “first Skeezix” strip but it will surely be the most expensive Gasoline Alley daily ever sold when it comes to auction. Much the same can be said for the daily of 23rd Novemeber 1927 in which Walt gets full and final custody of Skeezix, one which I was hoping to acquire but missed out on due to a lack of stomach. The strip has little going for it in the art department but is pretty significant as far as what it portrays.

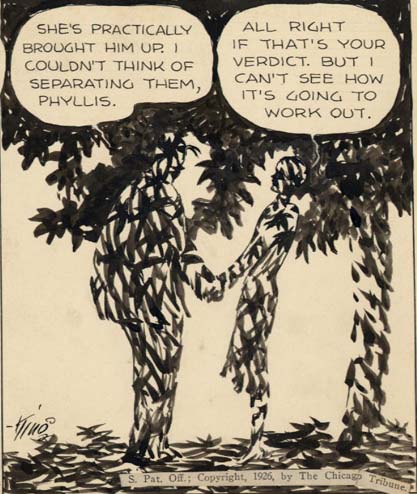

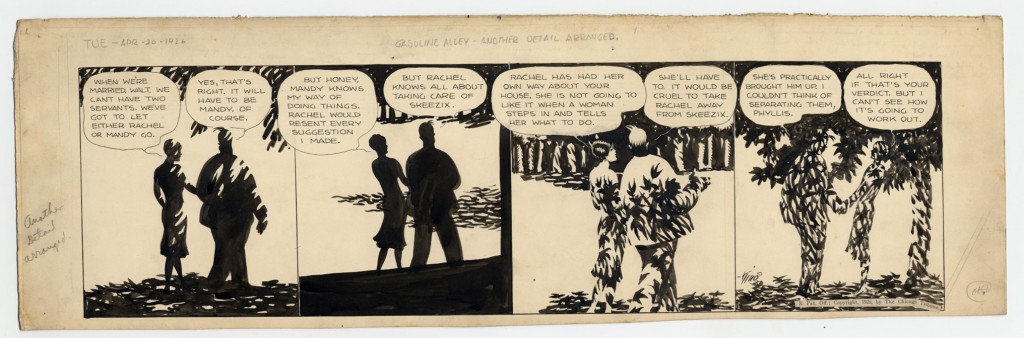

By comparison, if we consider the daily of 20th April 1926, we might say that there is almost nothing of significance being discussed; nothing except the fates of two black maids (for the uninitiated, the strip was hardly short of appalling “mammy” scenes in its early years).

Yet there can be little doubt that this is one of the most formally beautiful dailies that King ever drew. It is, of course, daring in presentation with little continuity in the backgrounds except for the impression of a forest. It is the two figures of Walt and Phyllis which push the narrative along, first proceeding down a path dappled with shadows, skirting the edges of an unseen jungle; then proceeding past the harsh vertical and diagonal lines cast presumably by a man-made structure; before settling on an Edenic scene under a tree.

[from the collection of Rob Stolzer]

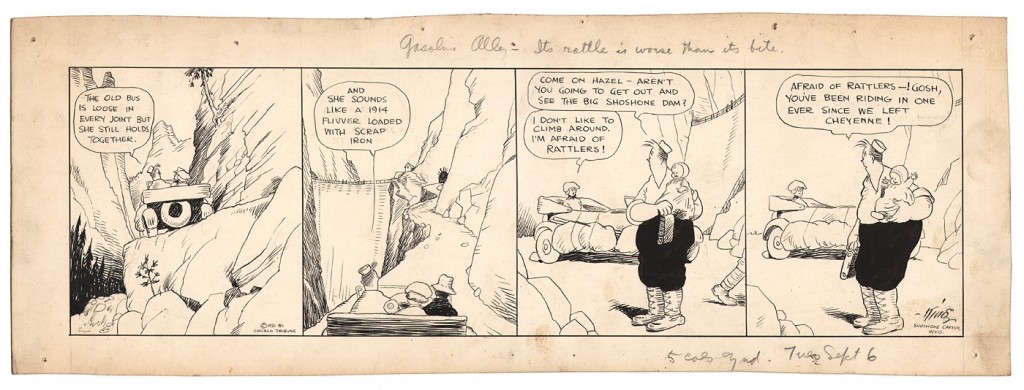

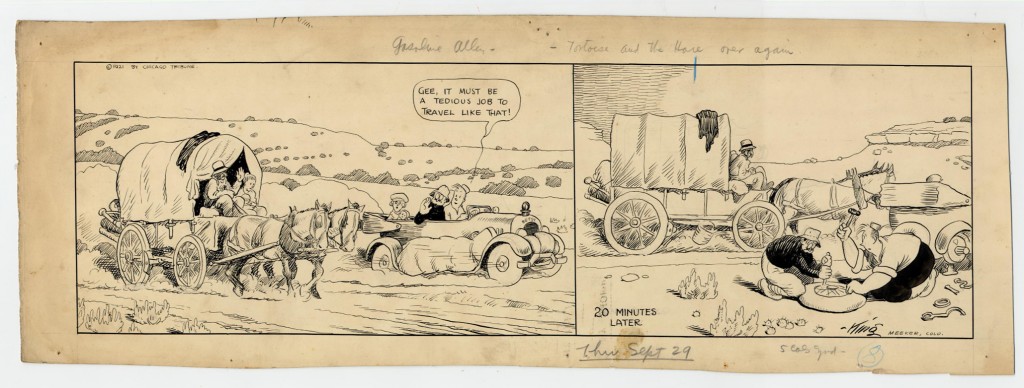

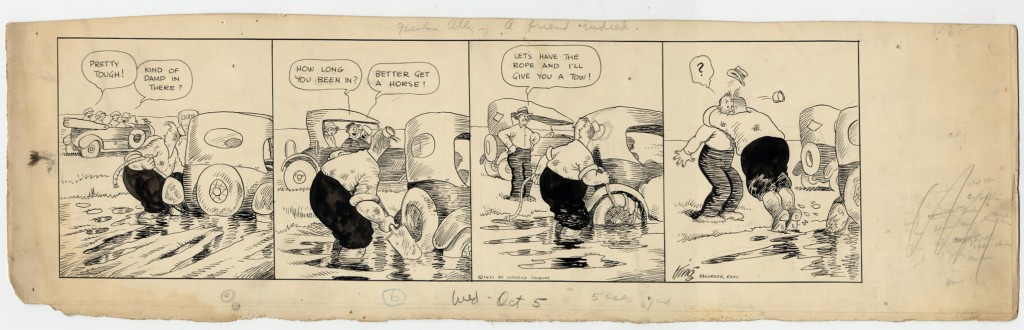

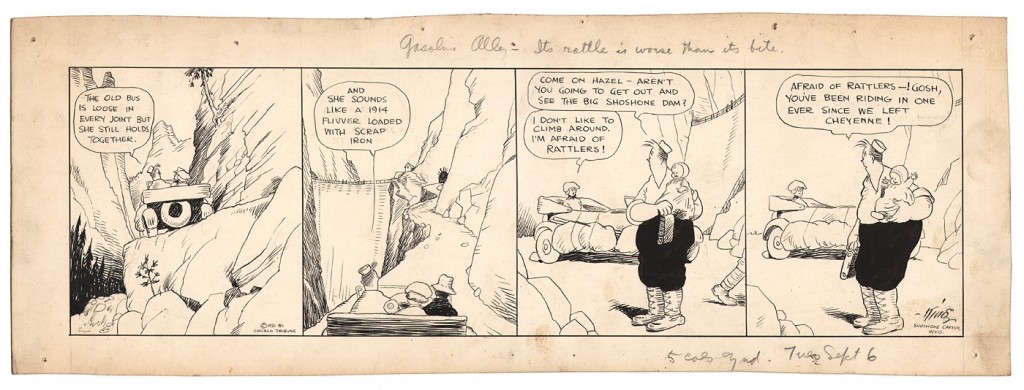

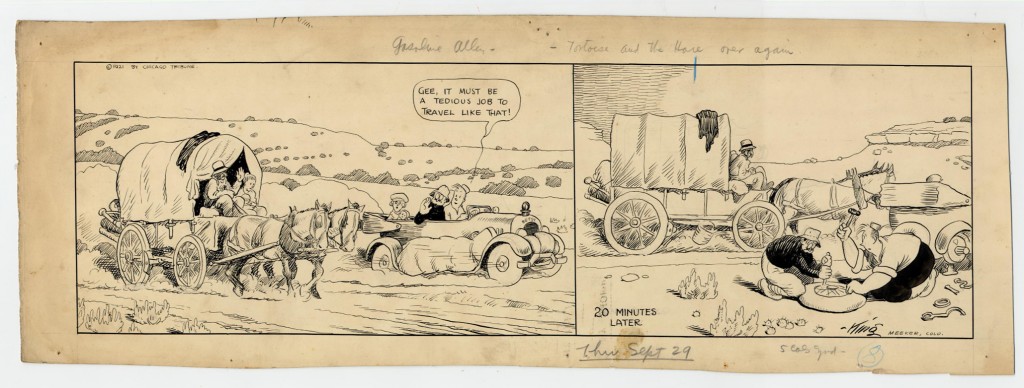

There was ever this mix of industrialization and nature in King’s early Skeezix strips, the most notable example being the tour of various National Parks in 1921 in which King lightly played out the tension between the old and the new…

…and the concomitant change in values.

The words provide the context for this minor masterpiece in King’s oeuvre—a mild dispute which is finally resolved harmoniously—the interplay of emotions entirely carried by the workings of the forest light which flickers tentatively in the darkness…

…before reaching a kind of balance as Walt and Phyllis arrive at a domestic compromise.

And is it a coincidence that in this discussion of two working class African Americans, we should see the figures of the very white and Caucasian Walt and Phyllis turn from deep black to a variegated pattern of shadow and light?

***

But let’s return to the question of price vs. value which I mentioned at the start of this article.

While the sale of the McFarlane cover may seem a losing proposition as an individual investment, there is every reason to believe that the high price will be turned to profitable ends by the main players in this game—the auction houses and retailers who carry art of an equivalent “stature”. The rumor mill has not dismissed the possibility that the art itself will be sold quite magically for a profit in years to come, the highly manipulable art of price ratcheting now coming firmly into play.

In contrast, one of the famous Gasoline Alley “woodcut” Sundays—a masterpiece of the form—sold for just over $20,000 just a few months back. To put things in even finer perspective, if every one of the current crop of Gasoline Alley dailies (about 300 as of 13th August 2012) sold for $2000 (a handful have sold for more, most have sold for much less), the entire proceeds would still be less than the amount achieved for the aforementioned McFarlane Amazing Spider-Man cover.

Even so, this prime set of Gasoline Alley dailies, are very likely depreciating investments which will find it hard to keep up with the rate of inflation. The nostalgia value for these strips is almost non-existent, the collectors of these dailies being well worn and with at least a little toe (if not a foot) in the grave. The decision to sell at this opportune moment when the Drawn and Quarterly reprints have had time to settle in was probably wise though the rate at which they have been released is less possessed of the finest marketing sensibilities. And while it is excellent news for collectors that Americans disdain so much this small corner of their rich cartooning heritage, it does suggest that the greater part of this significant Gasoline Alley collection should have found a home in a comics museum the likes of which does not as yet exist. This rather than being scattered to the winds, bereft of the aesthetic weight of its size and the sheer breath of art, storytelling, and gentle humor.

Further Reading

Robert Boyd complains about the hopeless philistinism of the McFarlane purchase.