My son drew these and said they were dragons behaving like cats. So here is a dragon behaving like a cat awake.

And here is a dragon behaving like a cat asleep.

This review first ran at The Comics Journal.

______________________

Steve Ditko

Strange Suspense: The Steve Ditko Archives volume 1

Fantagraphics

This is a collection of comics great Steve Ditko’s first published stories, mostly pulp horror from the early 1950s. I found it literally unreadable.

Usually when I write a review, I try to put in an honest effort to actually read every word. I gave it a go here and…well, this is what I found myself trudging through in the second story in the volume, “Paper Romance.”

It was too late for me to back down now! So I wrote the letter as soon as I got home. A letter that had been in my mind for years…telling everything about myself and hinting at what I was looking for in a man…the rest was to come if and when somebody answered my letter! The next few days dragged by with leaden feet and after a while I forgot completely about my letter…well not completely! But then…

Did you read that whole thing? If you did and you enjoyed it, you’re a hardier soul than I. “I got my letter and then I thought about my letter and then I thought about my letter some more and then I used a metaphor: ‘leaden feet’!” That’s just dreadful. And, yes, that’s the one romance story in the book, but the horror and adventure comics are not appreciably better; there’s still the numbing repetition, the tin ear, and the infuriating refusal to finesse said tin ear by leaving the damn pictures alone to tell their own story.

Whether this is Ditko’s fault entirely is unclear. Fantagraphics doesn’t give writer’s credits for the volume, which may mean that Ditko wrote the stories himself or, alternately, that the scripters are anonymous. Even if I don’t know who to blame, though, I sure as hell am blaming somebody for the fact that when the goblins surround Avery, we have text telling us “They decided it was time to surround Avery” so that Ditko has to squeeze the actual picture of the goblins surrounding Avery into an even smaller space. And even when the text boxes fall silent, we have the endless nattering of the dialogue balloons. If the haunted sailor says he hears a wild laugh once, he’s got to say it five times. It’s like having your tale of suspense shouted at you by your elderly deaf uncle . Who is stupid.

Even putting aside the writing, in terms of visual flow and storytelling, Ditko, at least at this point in his career, varies between mediocre and downright bad. He’s got some entertainingly loopy ideas, but he’s constantly burying his punchlines — in his riff on Cinderella, for example, the final panel is supposed to show you the good prince changing into a vampire and the three sisters with their legs ripped off so they fit the slippers. But it’s done so small I had to stare at it for a good 15 seconds before I could make head or tail of it, and then all I could think was — why do you need to pull a leg off to fit into a shoe? Wouldn’t you want to cut the foot instead?

But the solution to all of these problems is easy. Just sell your soul to the devil for the power to create an invulnerable super-worm with poison lipstick who will tear out your uncle’s eyes and replace them with wax. Or something like that. I’m not really sure of the exact plot ins and outs, because I just skimmed the whole damn thing, thank you very much, which was a much, much more pleasurable experience than reading those first couple of stories. Because, whatever Ditko’s limitations, even at this early stage in his career, he’s a fascinating artist with a bizarre and entirely idiosyncratic visual imagination. Eerily writhing smoke, expressive hands twisted into unlikely or even impossible positions, angled shots from up in the skylight — none of this will surprise anyone familiar with Ditko’s work, but it’s all as tasty as ever. In this volume I noticed especially his faces. Everyone in Ditko has these strong lined physiognomies that hover on the verge of caricature. The result in these horror titles is that humans and monsters aren’t so much opposed as they are on a continuum of potential deformity. Even Ditko’s hot dames have features which are too heavy, too malleable — they look like female impersonators, or like they’re wearing masks.

My favorite image in the book wasn’t typical Ditko at all, though. Instead it was this.

Usually Ditko’s drawings are crowded, even cluttered. This panel, though, uses negative space like a Japanese print. It’s an intriguing reminder that, along with the inevitable stumbles, apprentice work can also result in the occasional uncharacteristic, and surprisingly graceful, experiment.

There were a lot of great story arcs written during the Silver Age of Comics, which most comics historians agree spanned the years 1956-1970. But the best one, in my opinion, “If This Be My Destiny,” was published as a three-part story in “Amazing Spider-Man” issues 31-33, cover-dated December 1965 through February 1966.

But before we can analyze exactly why the story was so special, we first need to identify who the key player was in its creation, layout, pacing and overall story.

Stan Lee was attributed as the “writer” of the story in the credits, but he, as I discuss below, had nothing to do with the story arc’s creation. For while he wrote the dialogue after the pages were laid out and drawn, he did none of the plotting, and had zero input on the pacing, basic character interaction, mood, and story direction. All of that was done by artist Steve Ditko.

The “Marvel Method” of creating comics during this period was peculiar in that regards, especially for Lee’s top bullpen artists Ditko and Jack Kirby. When the process was first implemented by Lee in the early 1960s – ostensibly to save him the time of writing a full-blown script – he and the artist of a particular comic book would have a story conference, work out a plot, and the artist would go home and draw out the entire issue. The finished pages would then be given to Lee, who proceeded to add the dialogue.

But by the mid-1960s, Kirby and Ditko were so good at creating and plotting stories that Lee himself admitted in a number of interviews that he often had little or no input for story arcs. In fact, he often would have no idea what the story for a particular issue was going to be about until after the pages were delivered by the artist.

Lee himself details this Marvel Method process in an unusually candid interview he did for “Castle of Frankenstein” #12 (1968), a magazine that covered popular culture from that era:

“Some artists, of course, need a more detailed plot than others. Some artists, such as Jack Kirby, need no plot at all. I mean I’ll just say to Jack, ‘Let’s make the next villain be Dr. Doom’… or I may not even say that. He may tell me. And then he goes home and does it. He’s good at plots. I’m sure he’s a thousand times better than I. He just about makes up the plots for these stories. All I do is a little editing… I may tell him he’s gone too far in one direction or another. Of course, occasionally I’ll give him a plot, but we’re practically both the writers on the things.”

This was also true with Ditko and his early Marvel Method process on “Amazing Spider-Man.” He and Lee would have a story discussion, after which Ditko would leave, pencil out the story and then, inside the panels, write in a “panel script” (suggested dialogue and narration). He would then bring the pages back to Lee and they’d discuss the story from start to finish. Ditko would annotate any changes outside of the panels, and then he’d leave the penciled pages with Lee. Lee would then write in the final dialogue and the book would be lettered. Ditko then picked up the lettered pages, and made any of the annotated changes during the inking process.

But Lee really had no long-term vision for Spider-Man. He never thought about what he would do with the characters from one issue to the next. He’d just say, “Let’s make Attuma the villain,” and Ditko would have to talk him out of it. The glue that really held the Spider-Man direction and continuity together in those early days of the character was Ditko.

Over time, Ditko received more and more story autonomy and character development latitude that by about issue #18, he was doing the sole plotting chores with no input from Lee. But it took time for Lee to give Ditko what was then unprecedented plotting credit, beginning with “Amazing Spider-Man” #26 (July 1965), and ending with Ditko’s last issue, #38 (July 1966).

As with many aspects of those murky creative days at Marvel, Ditko’s credits raise questions. For example, why did Lee agree to give Ditko plotting credit, but not Kirby, whose “Fantastic Four” and “Thor” plotting autonomy was apparently quite similar? And why did Lee, when he finally did start giving artist and plotting credit to Ditko, suddenly, after one issue, expand his own credits from “writer” (his standard credit line for the first 26 issues of “Amazing Spider-Man”) to both “editor and writer”?

Around the time Ditko began receiving plotting credit, a rift between the two arose and, according to several Marvel staffers, was so acute, Lee would not speak to Ditko. It was during this year-long communication blackout period that Ditko wrote his Spider-Man magnum opus, “If This Be My Destiny.”

Additional evidence that Lee had no story input during this period can be found in “Amazing Spider-Man” #30, which set the stage for Ditko’s historic three-issue story arc. In that issue, the villain is a thief named The Cat, but Ditko also introduced, in two different parts of the story, henchmen for The Master Planner – the surprise villain for the “Destiny” story arc that was to start in issue #31. Yet because communication between Lee and Ditko had ceased, Lee had no idea who the costumed criminals were and misidentified them as The Cat’s henchmen – which, upon close examination of the story, makes no sense. It’s not until the next issue that the error becomes obvious to Lee and he gets a better grasp of Ditko’s storyline.

So, now that we have a better understanding about who created what for this historic story arc, exactly what is it that makes Ditko’s “Destiny” so great from both a literary and artistic standpoint?

How does one go about measuring greatness? After all, there are no established standards for greatness in comics, or, for that matter, the two creative disciplines that are merged to create them: art and literature.

Some argue that great art or literature is timeless, and that it appeals to our emotions in a compelling and riveting way. Others argue that it is something that breaks new ground.

Ditko’s three-issue story arc easily accomplishes all three, and a lot more.

We can glimpse Ditko’s personal, objective views about what constitutes art from his recorded statements for the 1989 video, “Masters of Comic Book Art.” Ditko said that based on Aristotle’s Law of Identity, “Art is philosophically more important than history. History tells how men did act; art shows how men could, and should act. Art creates a model – an ideal man as a measuring standard. Without a measuring standard, nothing can be identified or judged.”

It’s clear to me that Ditko, through his stories and art in “Amazing Spider-Man,” was striving to do just that: mold Peter Parker/Spider-Man into a positive heroic model.

Throughout his career, Ditko has always been a creative, experimental, thinking-man’s innovator. It was evident in his costume designs, character portrayals, settings, lighting, poses, choreography, etc. – literally every aspect of the comic book creative process. For example, no one before or since has created anything like Ditko’s multi-dimensional worlds for his Doctor Strange character. And his creative depictions of Spider-Man’s costume, devices, movement through space, and overall look set the standard for every single Spider-Man artist who has followed. I’ve been a fan of his work for 45 years, and to this day, I still marvel at how Ditko was able to take the totally fantastic and make it seem like it could actually be real.

Ditko was innovative in other ways as well. Unlike many of his contemporaries back then, Ditko had an eye on continuity, and started meticulously planning story arcs and sub-plots many months or even years in advance. Such was the case with his slow and methodical development of the Green Goblin‘s secret identity over a multi-year period, and his tantalizingly slow introduction of Mary Jane.

Ditko’s development of his “Destiny” story arc in “Amazing Spider-Man” #31-33 was no different. Ditko planted the initial seed for the arc way back in issue #10, when Peter Parker provided blood during a transfusion of his seriously ill Aunt May. As regular readers eventually found out, Parker’s selfless act of kindness turned out to be a ticking time bomb for his frail aunt, who began suffering ominous fainting spells in issue #29, and again in issue #30.

As I mentioned above, the mature, heroic side of Peter Parker and Spider-Man had been building for many months before the “Destiny” story arc kicked in – a steady drumbeat that would soon reach a deafening crescendo. At the same time, Parker was enduring important emotional lows and highs. For example, his long relationship with Betty Brant had been pulled wire taut in the months preceding “Destiny,” and was at the breaking point. Likewise, Parker graduated high school in issue #28, and was about to go off to college and enter what he hoped was a new and exciting chapter of his life. But despite his emotional roller-coaster rides, it was clear to the regular reader that Parker was growing more mature, determined and focused both as a normal person and as Spider-Man. He was no longer the silent doormat for his boss, J. Jonah Jameson, his high school nemesis Flash Thompson, or any other negative influence in his life.

It was at this convergence of events where “Destiny” began, and the reader soon found out just how mature, determined and focused Parker and his alter ego would be under the most harrowing of circumstances – circumstances that would have the highest emotional stakes imaginable for the character.

As the three-issue story arc opened with issue #31, the stage is set for what’s to come when Spider-Man stumbles across the Master Planner’s men fleeing, via helicopter, a location where they have just stolen some radioactive atomic devices. A battle ensues, but they escape. It is during this escape that the Master Planner’s underwater refuge – a key location later in the story – is revealed.

The scene shifts to Peter Parker’s home, where he waves goodbye to his Aunt May before heading off to his first day of college. The reader can see that she is gravely ill, but she’s doing her utmost to hide it from her nephew so he doesn’t worry. When Peter returns later that day, she can hide it no longer and collapses in his arms. Her illness is so serious, their family doctor admits her to a hospital. Peter is by her side until she falls asleep, and heads for home. Here the emotional roller-coaster starts its journey again as Peter tries to juggle college, lack of sleep, mounting bills, and Aunt May’s illness all at the same time. But Aunt May’s illness overshadows everything else and his new classmates find him aloof and distant.

As his money pressures mount, Peter changes to Spider-Man so he can look for news photo opportunities around the city – as taking news photos for “The Daily Bugle” is his only source of income. He gets a tip that a robbery will be taking place at the docks that evening, and when he arrives, he once more finds the Master Planner’s men attempting to steal a ship’s radiation-related cargo. Another battle ensues, and they escape again – this time into the water using scuba gear. As the issue comes to a close, an unseen Master Planner, in his underwater lair, mulls how Spider-Man is thwarting his attempt to use radiation secrets for nefarious purpose. But the final three panels are far more ominous: the doctors caring for Aunt May have finished their tests, and conclude that she is dying.

Issue #32, “Man on a Rampage,” opens in the Master Planner’s underwater hideout, and we quickly find out that he is actually none other than Dr. Octopus, one of Spider-Man’s most dangerous foes. The scene then shifts to Peter, whose relationship and money problems keep mounting. But things get even worse when he visits the hospital and the physician attending to Aunt May informs him that her terminal illness is being caused by an unknown source of radioactivity in her blood. Peter immediately realizes that the radioactivity must have come from his contaminated donor blood which Aunt May received during a transfusion many months earlier for a different illness.

And while the radioactivity is harmless to him, it is having a devastating effect on Aunt May. So not only was young Parker responsible for the death of his Uncle Ben when he first became Spider-Man, he may soon be responsible for the death of Aunt May. This emotional realization is perfectly portrayed by Ditko, along with Peter’s vow that he will not fail at saving a loved one again.

Parker then gets an idea. He tracks down Dr. Curtis Connors (aka The Lizard) – a blood specialist who he hasn’t seen since issue #6 – and, as Spider-Man, gives him a stolen vial of Aunt May’s blood, and begs him to see if he can discover a cure for his “friend.” Connors agrees and after some tests says that an experimental serum called ISO-36 might help – but it will cost money. Parker leaves, hocks all of his personal laboratory equipment, gets the money, and returns to Connors’ lab as Spider-Man. While they wait for every available bit of the rare serum to be express-delivered from across the country, Parker, a budding scientist in his own right, helps Connors with some preliminary lab research. Suddenly, Connors gets a phone call informing him that the ISO-36 was stolen by the Master Planner’s henchmen, and Spider-Man explodes into action.

In an effort to find the precious stolen serum, Spider-Man literally does go on a rampage, snatching up criminals and stoolpigeons, smashing down doors and rooting through every underworld nook and cranny across the city for any possible leads. As the clock ticks, we see Aunt May slip into a coma, Dr. Connors patiently waiting, and a desperate Spider-Man becoming more and more frantic.

Suddenly, after swinging into a blind alley, his Spider-Sense points him to a hidden trapdoor leading to the underground tunnel entrance for the Master Planner’s underwater hideout. Battling through dozens of henchmen, he slips through a sliding doorway into the tunnel. Alerted by one of his men that Spider-Man is searching for the stolen ISO-36, Dr. Octopus decides to use it as bait so he can kill Spider-Man, once and for all.

He places the serum in the middle of the cavernous domed main room of his underwater lair, and waits. Spider-Man enters, and despite a last-second warning by his Spider-Sense, the trap is sprung and a raging battle ensues. But Dr. Octopus soon finds out something is different this time, as Spider-Man is fighting like a man possessed. Startled, Dr. Octopus quickly shifts from offense to defense, and within minutes is no longer fighting, but trying to find a way to escape the madman he is facing. A main support beam is shattered during the fight, and as the machinery inside the dome begins collapsing, Dr. Octopus slips away. But Spider-Man is trapped.

For the last three pages of issue #32 and the first five pages of issue #33, Ditko creates the most masterful bit of sequential art of the Silver Age, and possibly ANY age. It is an artistic tour de force that needs no words to convey the story. The drama, stakes and emotional tension of the main character could not possibly have been wound any higher as issue #32 came to a close. And I don’t think there was a sentient reader alive back then who wasn’t gnawing his/her fingernails to the bone waiting to find out what was going to happen in issue #33.

As issue #33, “The Final Chapter,” opens, the powerful visual sequence begun in the previous issue continues. After a four-panel recap, we see a hopelessly-trapped Spider-Man buried under the weight of an enormous mass of machinery as the main room of the underwater hideout of Dr. Octopus begins to flood. Aunt May is dying, and the serum he needs to save her lies on the floor in front of him, just out of reach.

And just when you think it’s over for Spider-Man, and that he’s doomed to die, he once more thinks of Uncle Ben and Aunt May, taps a latent reservoir of sheer will and determination from his innermost being, and attempts one last time to break free. Ditko captures the agonizing struggle pitch perfectly, with sequential pacing that rivals that of the best comic book or film. And with one last mighty heave, he’s free (See Figures 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11).

But Ditko’s not finished. During the next 15 pages, Spider-Man must overcome even more physical and emotional adversity to save his aunt. But I’m not going to spoil the entire story arc. Grab a reprint of issue #33 and finish it yourself. You won’t regret it.

A few final points about the “Destiny” story arc and Ditko’s often underappreciated creativity.

First, the reason I showed wordless versions of the story’s pages was two-fold: to show how visually powerful Ditko’s storytelling abilities were, and to highlight just how crucial artists like Ditko and Kirby were to creating stories using the Marvel Method during the Silver Age.

Second, I want to make sure everyone understands just how much responsibility the artist had back then. In cinematic terms, Ditko not only co-wrote the screenplay, he was the storyboard artist, director, film editor, casting director, cameraman, cinematographer, production designer, costume designer, art director, stunt director, and set designer. Lee, on the other hand, co-wrote the screenplay, and did the “sound” editing.

So, while Lee’s dialogue certainly enhanced the story, Ditko was the creative force behind almost everything else. In that regards, if the story were a Corvette, Lee applied the paint job, pinstripes and some of the detailing, but Ditko designed the car, crafted all the parts, and assembled it.

‘Nuff said!

Folk psych droney dirges mix. Download There Is a Kingdom here.

1. Let No Man Steal Your Thyme — Anne Briggs

2. Lowlands — Anne Briggs

3. Born-Again Fool — Patty Loveless

4. If I Could Only Fly — Merle Haggard

5. It won’t Be the Last Time — Justin Townes Earle

6. Famous Blue Raincoat — Leonard Cohen

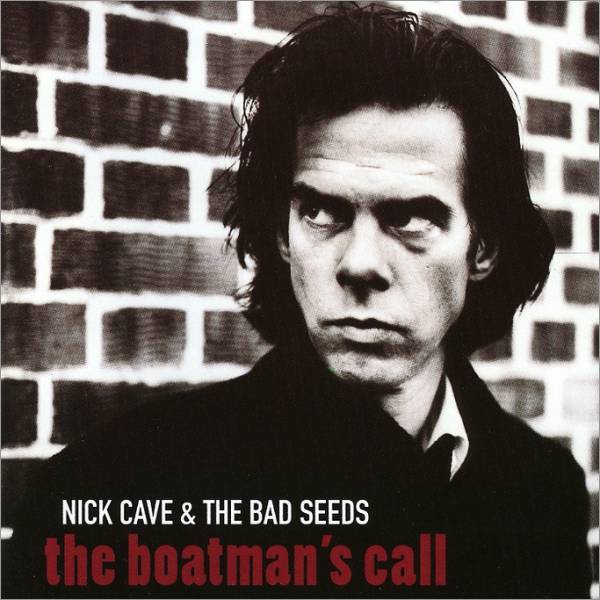

7. There Is a Kingdom — Nick Cave

8. A Detective Story — Tommy Flanders

9. One Man Rock and Roll Band — Roy Harper

10.Withered and Died — Richard and Linda Thompson

11. Motion Pictures — Neil Young

12. Violence — Low

13. Sally Free and Easy — Magic Hour

14. The Hand That Rocks the Cradle — The Smiths

Cloud Atlas

By David Mitchell

I approach contemporary science fiction with a certain wariness. Many of my friends are sci-fi/fantasy fans, and they are only too happy to recommend books. Invariably, whenever I read one of these books I’m left wondering, “Why did I waste my life reading that?” I’m not interested in reading another techno-military thriller, or a 20-volume “epic,” or a tedious story about a robot who contemplates the meaning of love. But after hearing multiple people praise Cloud Atlas, curiosity got the better of me. I’m glad to say that it wasn’t any where near as bad as I feared. I still didn’t like it , but I don’t feel like I’ve wasted hours of my life reading it. So that’s progress.

Cloud Atlas consists of six stories arranged in chronological order through the first half of the book, then the first five stories are revisited and concluded in reverse-chronological order in the second half. The stories are:

The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing – circa 1850, a diary written by an American traveler who spends time on the Chatham Islands before sailing for home. Much of the story describes the impact of Western colonialism on Pacific islanders, particularly the Moriori, who were nearly destroyed by a combination of Maori invaders and European diseases. Ewing is a relatively decent man, but he unthinkingly embraces the prejudices of his era until he meets a Moriori stowaway named Autua. Ewing saves Autua’s life, and the latter returns the favor by saving Ewing from the villainous Dr. Goose who planned to rob and murder Ewing.

Letters from Zedelghem – a series of letters written in 1931 by Robert Frobisher, an aspiring composer who flees his debts in England and moves to rural Belgium. There, he finds a position as the understudy to a famous but ailing composer. Robert is a bit of a rake, and seems poised to exploit the composer and his lusty wife for all they are worth. But his fortunes turn for the worse after a falling out with his employer.

Half Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery – a crime story set in 1975 California. Luisa Rey is a journalist working for a trashy tabloid who stumbles upon a major scandal involving a dangerous nuclear power plant and a murdered whistle-blower.

The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish – a contemporary comedy about an aging publisher who flees his troubles and inadvertently ends up in a retirement community. The community is run like a prison and the aging residents are treated little better than criminals. Most of the story details Cavendish’s escape attempts.

An Orison of Sonmi-451 – a dystopian sci-fi drama set sometime after a global nuclear war. Korea escaped destruction, but it is now ruled by a totalitarian-capitalist regime that relies on artificially-grown slave labor. Sonmi is one such slave, but she experiences an “ascension,” becoming fully self-aware and joining a rebellion. Sonmi is later captured and narrates the story to her interrogators prior to her execution (the orison is a recording device).

Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After – a memoir by Zachry, a Hawaiian tribesman who lived in a primitive farming community long after a nuclear war wiped out most of humanity. Zachry assists Meronym, one of the last remnants of a technologically advanced society, in gathering useful information. Zachry is eventually saved by Meronym after his village is wiped out by a more violent tribe.

The stories are interconnected in several ways. All the lead characters except Zachry possess the same comet-shaped birth mark, and Mitchell has acknowledged that they are a single reincarnated soul* (Meronym is the last reincarnation). Each story also acknowledges the existence of the chronologically earlier story. Frobisher reads Ewing’s journal, Luisa reads Frobisher’s letters, Cavendish reads a book starring Luisa, Sonmi reads a book about Cavendish, and Zachry encounters the orison that recorded Sonmi’s confession.

And there are themes common to all six stories, particularly the universality of violence, conquest, and exploitation. Ewing is a witness to Maori and European imperialism, and he is personally the victim of deception and violence. Frobisher is exploited by his employer. Luisa is nearly murdered by the corrupt owners of the nuclear plant. Cavendish is cruelly treated by the “caretakers” at the retirement community. Sonmi is enslaved, manipulated, and finally executed by an oppressive state. And Zachry’s entire world is destroyed by a predatory tribe. But Mitchell also acknowledges a gentler humanity that can triumph over our baser instincts. Autua saves Ewing, just as Meronym saves Zachry several centuries later.

For Mitchell, the triumph of good over evil is dependent on story-telling. This is particularly evident in Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After. As they lynchpin story, it binds the chronological narrative to the motifs that reoccur in the other five stories. It largely succeeds in highlighting Mitchell’s themes about human predation versus the “ascension” of the human spirit. Much of the story involves Zachry and Meronym fighting or evading the barbaric Kona tribe. Also, while Zachry’s tribe is more peaceful, he himself repeatedly struggles with violent impulses. At one point, Zachry actually has a conversation with the Devil (Old Georgie) and barely resists the temptation to murder Meronym. And Zachry’s tale suggests the moral value of story-telling. Zachry is the only survivor of a brutal attack on his tribe, and he eventually re-settles with Meronym’s people, who record his memories. His spiritual struggles and moral triumph serve as a inspiration to the surviving humans.

This theme re-emerges at the end of the second half of the Adam Ewing story (which is also the end of the entire novel). Ewing narrowly escapes murder at the hands of a (white) doctor who embraces a nihilistic, predatory philosophy. Ewing is saved by Autua, a dark-skinned ex-slave. These events cause Ewing to rethink his entire worldview, and he decides to become an abolitionist. In his words, “If we believe humanity may transcend tooth & claw, if we believe divers races & creeds can share the world … such a world will come to pass.”

So there are plenty of ideas bouncing around the book, and its division into six stories allows Mitchell to explore those ideas in six different genres. In each story, Mitchell demonstrates basic skill as a genre writer, whether he’s writing faux-memoir, mystery, or science fiction. In theory, Cloud Atlas should be an exciting and challenging book. In practice, the book fails to live up to its pretensions, largely because Mitchell’s ideas are not as profound as he seems to think they are. To summarize the main points of the book: if people choose to be good, then the world will be a better place. And story-telling is an effective way to convey moral lessons. The obvious response to these points is “No shit!” People have been well aware of these insights for at least the past two thousand years.

A more interesting observation might involve asking why people continue to do immoral things despite the countless stories intended to teach a moral lesson. If Cloud Atlas is any indication, Mitchell’s answer would be that humans are naturally predatory (they have an inner Old Georgie) and so there will always be at least some people who are violent, cruel, and selfish. That’s partly true, but it elides the fact that many violent, cruel, and selfish people nevertheless consider themselves moral, and they may even behave with kindness in a different context (for example, in the treatment of their own family). A sophisticated view of morality would have to look beyond a simplistic predator/victim relationship.

I don’t see much moral complexity in Cloud Atlas. The “good guys” are always likable, POV characters. They may be flawed, but their flaws are surmountable or at least forgivable. Ewing starts off as a racist, but he has an epiphany and embraces racial egalitarianism. Luisa Rey pursues journalistic truth and saves lives. Sonmi achieves greater self-awareness and defies a totalitarian state. Zachry resists temptation. Even the self-absorbed Frobisher isn’t that bad a guy, and he ends up being rather sympathetic in his final days.

The “bad guys,” on the other hand, are a uniformly reprehensible lot with no redeeming qualities. Dr. Goose is a psychopathic murderer. The businessmen in Half-Lives are almost comically villainous. The “caretakers” encountered by Cavendish are petty tyrants. And of course there is an oppressive state and the violent Kona tribe in the last two stories. Because Mitchell leans toward a simplistic, good vs. evil dichotomy, he can’t offer deeper insights about human morality. And without these insights the stories can only be described as forgettable genre works.

For example, Half Lives was a crime thriller, so Mitchell could draw ideas from an enormous collection of works. But while Mitchell replicates the basic formula and rhythm of a crime thriller, he doesn’t create a particularly compelling or memorable story. It’s an “airport novel” with a few liberal biases: corporations are evil, nuclear power is bad, journalists are noble heroes, etc., etc. All that righteousness becomes rather tedious, and it weighs down what would otherwise be a decent plot. Nor does it help that Luisa Rey is a dull heroine who stumbles through her own narrative while side characters perform all the heavy lifting.

An Orison of Sonmi-451 had far greater potential, as it borrows concepts from Huxley, Orwell, and the other great writers of dystopian fiction. In one sense, it’s an extremely derivative story, and Mitchell openly acknowledged his inspirations (primarily Brave New World and 1984). Being derivative doesn’t necessarily have to be a mark against it, as writers are constantly stealing ideas from each other. But Mitchell only steals the surface of ideas, and he adds nothing new to the genre. Huxley was interested in the relationship between eugenics and class (mostly because he belonged to a a family of eugenicists), while Orwell was interested in propaganda, particularly the manipulation of language. Mitchell touches a little on eugenics and propaganda, but he does little more than regurgitate older ideas. He’s far more interested in writing a story about a heroic slave who triumphs over her oppressors, even from beyond the grave. Though she was executed, the novel suggests that Sonmi’s confession become public knowledge and inspire a slave rebellion. She even comes to be worshiped as a goddess in Zachry’s time. It’s so predictably uplifting I wanted to puke. I’m not suggesting that the triumph of good over evil is objectionable per se, but it seems absurd to take the ideas of dystopian futurists and tack on a happy ending straight out of a Hollywood blockbuster.

Though the happy ending approach may explain why Cloud Atlas will soon be in a theater near you.

_________

Somehow, I have a collection of some of Geoff Jones’ work on the Teen Titans sitting on my shelf. It’s called “The Future Is Now”, and includes Teen Titans 15-23 from 2005, according to the copyright page. Honestly, I don’t know how it got here. I didn’t buy it; I know my wife didn’t buy it. Maybe somebody who thinks comics are still for kids gave it to us for the boy? I don’t know; I’m stumped.

In any case, Matt Brady’s epic Johns takedown from September, and some of the defenses of Johns which resulted, made me wonder if I should check him out (especially since, for whatever mysterious reason, I can do so for free.) In particular, I have to admit that I find this sequence from (I think?) some Blackest Night bit really hilarious.

Zombie mothers vomiting rage bile on their zombie offspring — that’s solid, goofy entertainment. I’d read a whole book of that for free.

Alas, “Teen Titans: The Future Is Now”, does not include any rage-bile vomiting, nor any zombie babies. Still, the first couple pages are kind of enjoyable. Superboy (who is a clone of Superman with telekinetic powers) is going on his first date with Wonder Girl (a new one named Cassie Sandmark, not Donna Troy — just in case anyone cares.) Anyway, she shows up late because, as she said, she wasn’t sure which skirt to wear, he tells her she looks amazing, they flirt and talk about taking it slow, and then Superboy (who isn’t totally in control of his powers yet, I guess) accidentally uses his X-ray vision and sees through his clothes, which he obviously finds super-embarrassing, albeit not entirely unpleasurable.

Not that this is great comics or anything, but it’s competent, low-key, teen superdrama in the tradition of Chris Claremont and Marv Wolfman. The art by Mike McKone and Mario Alquiza isn’t especially notable either, but it is at least marginally competent in conveying spatial relationships and expressions. Superboy covering his face with his hand is cute, for example. I could read a whole trade of this without too much pain or suffering.

Unfortunately, I don’t get a full trade of Claremont-Wolfmanesque teen super soap opera. I only get about four pages. Then Superboy is pulled into a dimensional vortex and Superboy from the future appears, and then there’s a crossover in the 31st century with the Legion of Superheroes, and then we’re back in the near future meeting the Teen Titans’ future selves who have all gone to the bad, along with a raft of other future-selves of guest stars…and then there’s a crossover with what I guess is the Identity Crisis event, which involves Dr. Light and Green Arrow and again about 50 gajillion guest heroes.

Luckily, I’ve been wasting my life reading DC comics for 30 years plus, so I know who all the guest heroes are, more or less. I know who the Terminator is, even though no one bothers to tell me; I know what the Flash treadmill is, even though it’s really not explained especially well. I even know why Captain Marvel Jr. can be defeated by a video-recording that shows him saying “Captain Marvel.” And if that last sentence made no sense to you, consider yourself fucking lucky.

So, yes, I can figure out what’s going on. But why exactly do I want to spend several hundred pages watching Johns move toys from my childhood from one side of the page to the other and then back again? I’d much rather find out more about Superboy and Cassie Sandmark. They seemed like smart and maybe interesting kids. But whether they are or not, I’ll never know. Johns is so busy throwing the entire DC universe at his readers that we never get to learn much about the characters who the book is ostensibly about. Honestly, I had to look at the opening credits page of the book when I was done to even figure out who’s supposed to be in this version of the Teen Titans. The team virtually never even fights as a team, much less slows down long enough to engage in even perfunctory character development. Cassie and Superboy’s romance is barely mentioned again; instead, the big subplot/emotional touchstone is Robin dealing with the death of his father — a death which appears to come out of nowhere, presumably because it was part of some crossover in some other title.

In a spirited defense of Geoff Johns, Matt Seneca argued that Johns sincerely believed in hope and bravery, and was “creating a fictional universe with no relation to ours whatsoever but using it to address the most basic (or hell, base, i’ll say it, who cares) human emotional concerns.” Maybe I’m reading the wrong Geoff Johns comic, but I have to say that there’s precious little of hope, or bravery, or of human emotional concern, base or otherwise, in these pages. Mostly there’s just a commitment to continuity porn so intense that even the most rudimentary genre pleasures are drowned in a backwash of extraneous bullshit.

Maybe Johns could tell a decent story if he had an issue or two to himself without some half-baked company-wide storyline to incorporate. But since it’s pretty clear from his career that he lives for those company-wide storylines, I’m not inclined to cut him much slack. As it is, I picked this up hoping to get a nostalgic recreation of the mediocre genre pulp of my youth. “Nearly as good as the Wolfman/Perez Teen Titans” — that doesn’t seem like it should be such a difficult hurdle. And yet there’s Johns, flopping about in the dust, the bottom-feeder burrowing beneath the hacks in the turgid swill of the mainstream.

This was originally published in Tagesspiegel. It is translated by Marc-Oliver Frisch.

_______________________

Although, as with Abecederia, Blexbolex is once again paying tribute to pulp culture, he remains best known for his children’s books: People, for instance, received a “Most Beautiful Book in the World” award at the Leipzig Book Fair in 2009. But in his works for mature readers, the beauty results from the composition of horrors founded in reality as well as in fantasies produced for a mass audience.

And so, one line tells all about No Man’s Land, Blexbolex’s most recent pulp-culture tour de force: “At the end of the road I see on the top of the highest mountain the ruins of the same temples made of papier mâché that I once saw in a Tarzan book.” An obviously absurd reference to Tarzan’s dime-novel, film and comics incarnations—after all, without knowledge of the pertinent publishing history and the fact that papier mâché is also known as pulp, such references are inscrutable.

On the previous page, Blexbolex—alias Bernard Granger, a Frenchman now living in Leipzig—refers to the “covers of a science-fiction novel by Roy Rockwood.” Rockwood is a collective nom de plume under which adolescent utopian adventure stories by multiple authors were published at the onset of the 20th century, including Bomba the Jungle Boy, the tales of one of Tarzan’s many epigones.

Consequently, the tale of an agent’s attempt at self-discovery in no man’s land, between all fronts, can be difficult to follow. Mainly, this is due to the author’s playful use of meta levels, which involves a nameless narrator visiting classic adventure-genre locations such as submarines, ghost ships or mysterious islands before, finally, returning to his own self. In a recurring motif of this journey, the main character is repeatedly breaking through reflective surfaces, be they windows or mirrors. Thus, the references—in images and words—to the moldering refuse of bygone cultural ages prompt reflections on identity. Blexbolex primarily relies on an associative reception, so institutions with a sense of moral entitlement, such as state and church, may well be depicted here as being circled by instinct-driven sharks. The conflict over the freedom of imagination and, consequently, the future, which is also a struggle over ethics, is illustrated by the character of Banks—a composite monstrosity made of multiple personalities and artificial flesh in whose services the protagonist finds himself—and by the hero’s opponents and intermittent collaborators Gregory Rabbit and Puss in Boots. It is a conflict that is carried out with excessive ruthlessness by both sides, but, at least in moral terms, can be won by neither.

This portrayal of a general lack of orientation is emphasized by references to authors writing under collective pseudonyms, whose interchangeability within the pulp mass-production chain has bred equally interchangeable role models with immutable heroic attributes. Everything seems right and nothing wrong, the means applied degenerate into ends in themselves, and moral boundaries are continually adjusted. Affirmative identification gives way to conceptual randomness. Blexbolex creates wild phantasmagorias of opposites growing ever closer in their approach. He stages them by way of a clear separation of contours made possible through the limited use of colors, as well as deliberately established exceptions from this rule, in which the colors overlap in ways that might seem unintentional.

These graphics, made digitally and sometimes resembling defective screenprints, are influenced by children’s-book illustrations, but also by the covers of science-fiction books. The “Série noir” paperbacks by authors Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett or Jim Thompson published in 1950s France constitute another influence. It is those writers’ style and variety of characterization that resurfaces in the prose below the illustrations. Another influence is “neo-noir” author James Ellroy’s, whom Blexbolex holds in high regard. Blexbolex’s literary approach, on the other hand, evokes William S. Burroughs’ cut-up technique in Nova Express. As a result, readers have to continually reassure themselves of the continuity, taking their cues by turns from graphics and words. Conceptually, at last, there is a kinship with the Fernando Arrabal play And They Put Handcuffs on the Flowers.

True to the aforementioned literary traditions, No Man’s Land provides an opaque type of social criticism in a drug-induced fever haze, delivered with visual three-color precision and predetermined breaking points. Regardless of the debatable timeliness of this vernacular, and despite its consummate delivery, Blexbolex’s wallowing in the beauty of the trivial, which is fully accessible only to adept readers, unfortunately represents a big hurdle when it comes to receiving the message.