I think I forgot to introduce myself last time, so I’ll do that now. Hi, I’m subdee, short for sub_divided. I’m still not sure what this column will be about, but I have a feeling it’s going to involve a lot of very popular, very commercial, but nevertheless very weird Japanese comics; and Kpop.

With that out of the way, I was reading this great analysis of Star Trek: The Next Generation over on Grantland.com when I came across this paragraph about Harry Potter:

One of the reasons J.K. Rowling’s books exerted such an appeal over every sentient creature on earth is that they resolved, indeed fused, a cultural contradiction. She took the aesthetic of old-fashioned English boarding-school life and placed it at the center of a narrative about political inclusiveness. You get to keep the scarves, the medieval dining hall, the verdant lawns, the sense of privilege (you’re a wizard, Harry), while not only losing the snobbery and racism but actually casting them as the villains of the series. It’s the Slytherins and Death Eaters who have it in for mudbloods, not Harry and his friends, Hogwarts’ true heirs. The result of this, I would argue, is an absolutely bonkers subliminal reconfiguration of basically the entire cultural heritage of England. It’s as if Rowling reboots a 1,000-year-old national tradition into something that’s (a) totally unearned but (b) also way better than the original. Of course it electrified people.

Have your cake and eat it too! How many pop cultural flashpoints does this apply to?

Twilight: they are dangerous immortal creatures of the night who want to eat you up (in all senses), but the good vampires practice self-control and abstinence before marriage, while only the bad ones give in to their base desires.

50 Shades of Grey: BDSM is hot, but people who are into BDSM are emotionally damaged. Never mind how damaged they are, though, because BDSM is hot! Also, the characters look a bit like Edward and Bella from Twilight. But you bought the book because it is popular, not because you wanted to read about all that.

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo: violence against women is bad, and we will prove this by repeatedly exposing the heroine to violence. Also, she’ll sleep with the married, middle-aged writer-narrator, because he is supportive and nonjudgmental. This will never blow up for him, or anything like that (though it might strain his marriage a little bit).

Pretty much any comic that decries violence against women while also making it a major part of the narrative… (paging Frank Miller, Frank Miller to the table).

While these things are fun to list, they mostly don’t involve an “absolutely bonkers subliminal reconfiguration” of the literature of an entire Imperial power – rather, they are mostly mild-to-medium exploitation fare that decry sex acts while also pleasurably indulging in them. In fact, I feel that by bringing them up, I am diluting the purity of the original author’s idea, which he goes on to discuss in terms of Star Trek: TNG being a fantasy of a conservative, hierarchical society (Starfleet Academy) organized around the pursuit of liberal ideals like inclusiveness and multiculturalism.

I can think of a recent novel/anime/manga series that might fit, though: and that’s Sainkoku Monotagari.

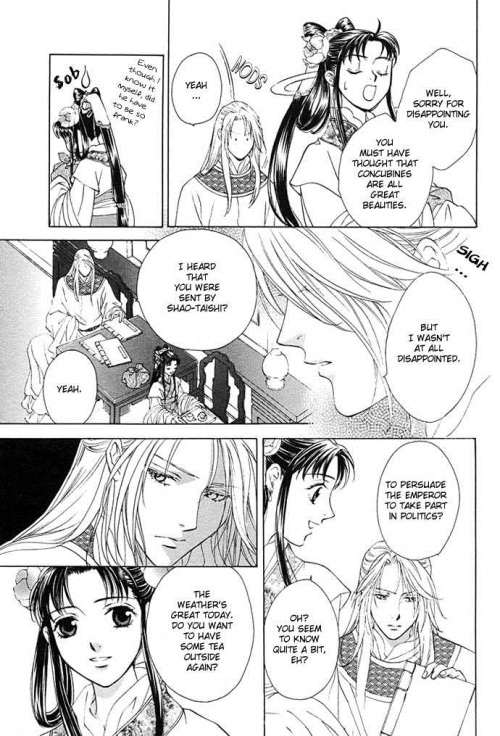

Clumsy girl + multiple hot guys with long flowing hair and robes = must be shoujo

Saiunkoku Monotagi, “the story of the country of many-colored clouds,” is a light novel series centered on the adventures of a young would-be government official, who dreams of passing the imperial exam and loyally serving an Imperial China-esque country. The catch is, she is female, and therefore forbidden from sitting the exam.

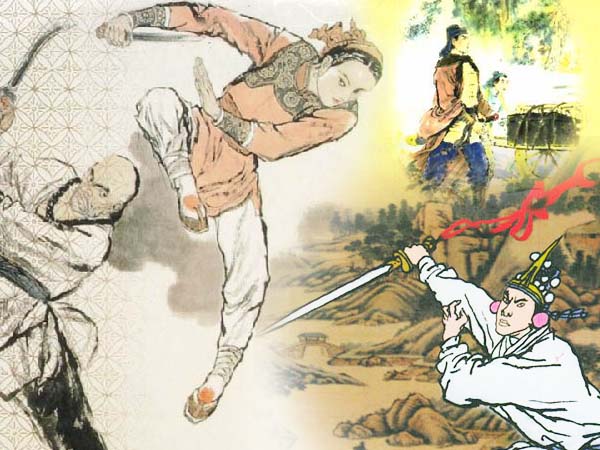

You see where I’m going with this, right? There’s a history of these Fantasy Imperial China stories in East Asia, but traditionally the women in these stories are either great marital arts masters (if wuxia) or supernatural creatures (if supernatural kung-fu). In the more “realistic” palace-drama stories, meanwhile, they are either married to/the daughters of male characters; or evil harridans who work behind the scenes, through the men with official positions. They don’t study hard and work diligently to accomplish great feats right out there in the open…

Yeah, why not!

Sainkoku isn’t the only story to look at history and imagine a better place for women, of course. It’s been compared to the 2003 K-drama Jewel in The Palace, about the Joseon Dynasty’s first female court physician, for instance. (And indeed the plot of Saiunkoku – first volume published in November of 2003 – shares many similarities with the plot of Dae Jang Geum.) Looking beyond historical dramas, there have been an even greater number of fantasy re-imaginings. Here’s an excerpt from the TV Tropes entry for Feminist Fantasy:

Another type of Feminist Fantasy is a feminist retelling of an old story, like a fairy tale or folktale. These are very popular nowadays, and seem to be the way this generation of Disney princesses is turning out—see Enchanted and Princess And The Frog. The former is completely self-aware and sends up the traditional Disney Princess archetype, and the latter is about a princess who wants to be a businesswoman and ends up with a guy along the way.

On the Princess and the Frog –> Enchanted continuum, Sainkoku falls in the middle, but closer to Princess and the Frog (straightforward pursuing-a-of-dream-that-does-not-involve-a-man) than to Enchanted (purposeful deconstruction of genre tropes).

Which genre tropes are we talking about, though? Reverse-harem tropes, where the female protagonist is inexplicably surrounded by hot men who compete for her attention? Shoujo tropes, where the protected, naïve main female character betters the lives everyone around her with the strength of her pure love? Palace Drama tropes, where factions cross and double-cross each other in a struggle for political power? Wuxia tropes, where supernaturally gifted swordsmen wander the countryside righting wrongs or at least testing their skills?

If you picked E, all of the above, you’d be right. Sainkoku is a palace-drama story dressed in shoujo reverse-harem clothing, with some wuxia and supernatural elements thrown in to keep the audience interested.

See this page for more on wuxia

In Japan, most fans are fans of the novel series, first, and of the anime series (released but now out of print in the US) and the manga series (currently publishing under the Viz – Shoujo Beat line) second. If they are really fans, they might also collect the mini-novels and calendars; read the spin-off novels focused on other characters; and listen to the drama CDs by the anime voice actors. SaiMono, in other words, is an institution with a wide reach… JK Rowling, incidentally, is currently at work on a spin-off novel about Sirius…

As far as who reads the books: SaiMono isn’t just a shoujo series targeted at young girls, it’s also one of the pinkest shoujo series ever. Check out these covers:

Surrounded by beautiful men, check, pink, check, flowers, check, long flowing robes and hair, check and check…

In fact, “pink” is more true of the anime series than of the novel series, whose covers actually become progressively less pink as time goes on. Still, it’s partially thanks to the breast-cancer-awareness levels of pinkification going on in the anime and early novel illustrations that my friend Charmian – notesonleaves – spent so long trying to convince us that Saiunkoku Monotagari is a strong dramatic story outside of the “reverse harem” and “anachronistic girl power” and “shoujo whitewashing of brutal history” trimmings. And she was right! Actually most of it is politicking and character development. To hear more, read on…

In Saiunkoku, the bad old days of civil war, famine, poverty and unpredictable politically-motivated assassination are within the living memory of most of the cast. Not only that, but these events – and dysfunctional family power struggles – have left most of them with PTSD, or personality disorders, or other remnants of trauma. In the middle of this group of very competent, but very damaged weirdos, Shuurei sticks out not because she is especially sheltered, but because she was able to depend on her family at all. The past playing itself out in the present, especially through barely-suppressed memories of past trauma, is another thing Saiunkoko Monogatari shares with Harry Potter, of course.

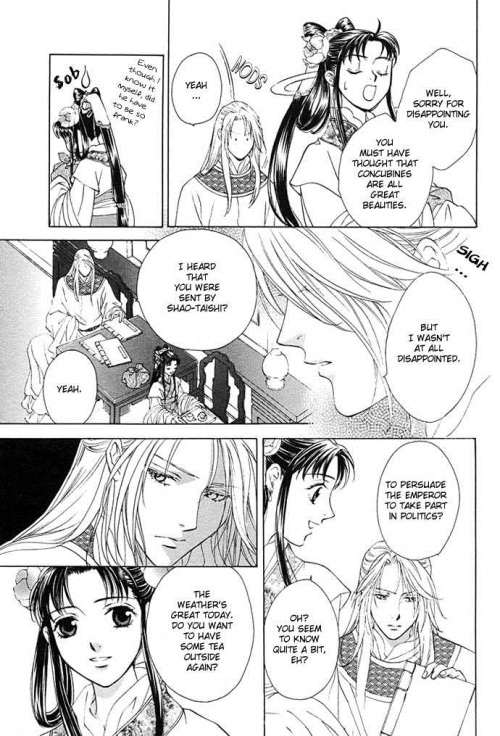

On that note, while the SaiMono-the-manga is mostly just a mechanism for delivering the story of the light novels, one place it really shines is the conveyance of subtle shifts of emotion – especially when it comes to Shuurei’s main love interest, the King –

Ryuuki, who became King by default after his older siblings all eliminated each other

It’s against this background that the story takes place, initially framing itself as the story of Shuurei pretending to be a member of the harem so she can get the thrice-shy Ryuuki, who is pretending to exclusively like men, to participate more in his own government.

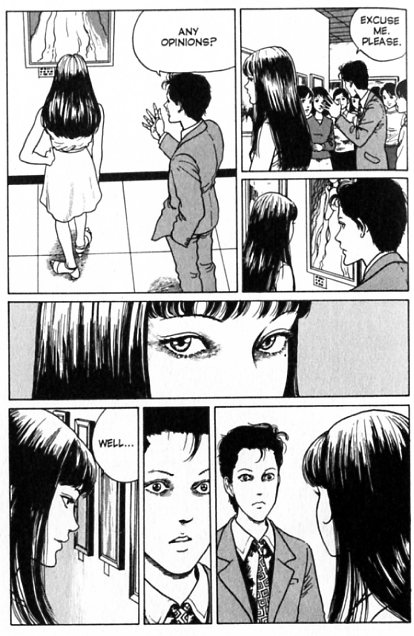

So since this story begins, literally, within a harem, let’s first talk about the reverse-harem angle. SaiMono owes a big debt to Fushigi Yuugi, the story of a modern girl sucked into a fantasy novel. Miaka finds herself at the center of a web of beautiful and damaged men, despite being, like Bella and Sailor Moon, a clumsy and gluttonous teenager without many traditional leadership qualities.

Fushigi Yuugi’s Miaka and Tamahome

Measured against this yardstick, Shuurei emerges largely as a refutation. She’s not clumsy or gluttonous: she’s good with money and skilled at a classical instrument (the ehru). Furthermore, Shuurei’s goals stand directly in contrast to Miaka’s goals: to serve her country impersonally and professionally as an official, relying on her own intelligence and skills rather than a man.

A traditional feminine failing possessed by the protagonists of these kinds of stories – because, let’s face it, they aren’t cute if they don’t have at least one – is not being able to cook, but the story explicitly makes Shuurei a great cook. Her father, a mild-mannered librarian with a hidden ruthless side, is the one who cutely can’t cook.

All is not refutation and subversion, however. Shoujo plots work better if their main characters are a bit naïve or idealistic, so they will work to change the system rather than accept their place within it. This is the case in Sainkoku, where Shuurei stands out among the traumatized cast as having been unusually sheltered. She’s helped, often secretly, by very many men throughout the narrative, including her father (secretly a SPOILER), her retainer (secretly a SPOILER SPOILER), her uncle (with SPOILER family connections); and the King, who wants to marry her but in the meantime will support her dream.

What’s interesting about all of these sheltering men, actually, is the way that SaiMono insists that the male urge to shelter young female relatives is at least partially pathological. Her father and the retainer, for instance, are secret – or maybe not-so-secret – psychos who are largely genial and apathetic in all things – until you threaten their loved ones (and isn’t that usually considered a feminine quality – the mother bear protecting her cubs?). The worst culprit in the arena of psychotic over protection, though, is Shuurei’s loving uncle Reishin, who is so determined to love and protect her from afar that he can’t even approach her, but only watch over her secretly. Even his friends think he’s a creep.

Within the story, the fact that Shuurei has been sheltered is actually a problem – it gets in the way of her being an official. The male cast are constantly watching her, and constantly telling each other not to interfere too much – to let her make her own mistakes and learn from them.

So SaiMono is a fix-it story, designed to rectify this one galling aspect of otherwise very enjoyable palace dramas: that there’s no space in them for strong female characters to pursue their (non-romantic) dreams. Not only is it a fix-it story, it’s one that sticks with its principles even against what the readership might like to see. For example, even the other characters, after a certain point, are rooting for Shuurei to end up with Ryuuki – but to do that would be to throw the story back into that other kind of narrative, of women working through men. She can’t marry him without giving up her dream, and he can’t make her do it without betraying her trust. The two premises of the story, that it’s a shoujo fantasy and that it’s a feminist fantasy, are at odds with each other. It’s not clear until the very last moment which one will win out.

A properly feminist story can’t have only one good female characters, of course: it also needs strong female role models. So SaiMono has a character who’s a princess with wuxia skills; another who’s a high-class courtesan owner of a brothel; another who’s a ninja; another who’s an inventor; and so on. The author appears to have put some thought into Sainkoku as a work of feminist fantasy, in other words.

That being the case, are the old bugaboos, the evil women with special powers, exorcised in this story? And are those who don’t think it’s appropriate for a woman to become an official recast as the villains, the way they are in Harry Potter? Sort of, but then again not really. There *is* an evil supernatural woman (although, on the other side of the ledger, also a good one). Shuurei is on the side of progress for women and inclusiveness in government, but also on the side of entrenched “major clans” over the wishes of the members of the petty nobility. Since there are a lot of factions, it’s hard to say who the “villain” is, apart from the people Shuurei has to win over.

That’s because SaiMono, despite initial premises, is committed to the idea that the world is complex. For instance, passing the exam doesn’t magically confer respect upon Shuurei, who continues to struggle with others’ perceptions that she is not capable. Similarly, it’s not enough for Ryuuki to suddenly decide that he wants to participate in the leadership of country: there are forces that have already moved to fill that role, and some of them are no less patriotic and well-meaning then him, and are much more competent.

I mean, don’t get me wrong: SaiMono is still young adult fantasy entertainment. Even “complex” issues tend to have simple solutions, as when Shuurei fixes the fortunes of a poor province with no natural resources by establishing a university there. Still, simplified or not, these kinds of plots are what I was hoping to see in The Legend of Korra, another story about a young, sheltered female protagonist with the potential to do great things. Korra let me down when the writers supported her choice to become a vigilante, but SaiMono surprisingly held up.

Korra looking over Ba Sing Se, the capital city of the Earth Kingdom and a complicated place.

Sainkoku Monotagari is idiosyncratic in other ways besides just the commitment to a feminist message. For instance, the author has a favorite reoccurring character type: the seemingly-well-adjusted mild-mannered underachiever, who turns out, almost invariably, to be a scarily competent and ruthless person. In the world of SaiMono, younger siblings very often assume leadership within clans while their more-damaged overachiever older siblings play hooky. There’s also the fact that the series’ main love interest, the King, is bisexual – a surprising angle, and possibly the most subversive thing about the series. Although, sadly, this plot point doesn’t get a lot of play after Ryuuki decides that Shuurei is the love of his life and that he’ll take only one wife.

Returning to the original premise of this post: perhaps that opening quote doesn’t apply as well as I thought, as there is very little that’s “subliminal” about the feminist retelling of this series. It’s not only a clear attack on the idea of separate roles for women, but also pretty careful to include a wide variety of female role models. On top of that, though I’m not familiar enough with this to say for sure, I do sometimes get the idea that “subversion” is a wuxia genre trope to begin with… although then again Saiunkoku is more of a palace drama than a wuxia story…

A better case might be made for some of the other idiosyncrasies of the series: for instance, Sainkoku’s take on standardized test-taking (passing the test is when your problems begin, not where they end). Or how about the insistence that birth order and skills are less important to success than personality and temperament? What about all those “lazy” hidden genius characters who don’t work hard but succeed anyway, but then throw that success away? …Actually who am I kidding, that’s not a subversion, that’s the premise of lots of Japanese fiction. They are really entertaining, though.

Ran Ryuuren, eccentric genius #10 in an ongoing series

Since this article started with a discussion of Harry Potter, I’ll end with a short list of other ways in which it is superficially similar to JKR’s bonkers subliminal reconfiguration: first of all, an emphasis on wacky hijinx among a large ensemble cast; related to that, a strong sense of character and of individual characters having their own motivations and lives outside the main storyline; finally, the nominal “mystery” plot of each volume – which is however much less mysterious after all the politicking and hijinx are stripped away.

Finally, of course, it’s a massively popular series! Light novels series, anime, manga series, voice actor drama, tons of character goods and officially sanctioned side-stories and spin-off novels…. there’s a Saiunkoku machine. And no wonder. I feel like some bronies should be discovering Saiunkoku, which is another one of those sparkly pink woman’s stories purposefully built to include asskicking as well as dark, tragic pasts. Maybe if the anime weren’t out of print, or the characters didn’t have such damnably difficult to remember names (Shuurei vs Shuuei vs Seiran vs Seien vs Shouka vs Shoukun vs Shusui). If the anime ever gets put back into print, perhaps we’ll see.

Or, you know, young adult entertainment