It’s that season again. Events related to comics, manga and related entertainment are happening all over the world even as we speak.

Big and small, these events have several things in common – fans, many of whom are not otherwise social creatures, gather to share their love of a niche form of entertainment. If you’re used to American events, you’re used to mob scenes, long lines while people lounge around, sit on the ground…even pitch tents while waiting and general chaos caused by people swinging giant weapons in crowded spaces. People push past one another, run through the halls carrying large bags and props and shove and crowd their way to popular vendor tables.

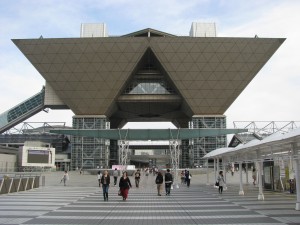

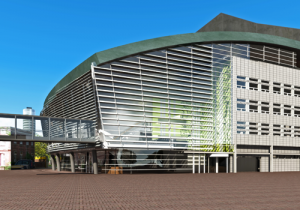

In stark contrast, at the largest comic event in Japan – the twice-a-year Comiket, held at Tokyo Big Sight, there are distinct, mostly unwritten, rules of etiquette. Some of these are to allow for crowd management, some are simply built up over years of attendees acting politely and considerately.

This year I was also able to attend a small convention in The Netherlands, Yaoi and Yuri Con. With a few hundred people, crushing lines were not going to be a problem, and etiquette was more or less, “don’t be a jerk.” The gap between these events seems almost insurmountable, until you scratch a little past the surface. So today, I want to talk about the Big and the Small of anime/manga fandom. Let’s start with the Big.

Personally, I only go to Winter Comiket. Big Sight is open on the sides, so even if it is a cold day, Comiket provides a warm coat of people. I cannot imagine how sticky and smelly Summer Comiket must be and I hope to never know. Basically, there are so many people at this event, that I commonly refer to it as “a ride made of people.”

There is nothing at any American event even remotely approaching the crowd management at a show like Comiket, which reportedly gets 200,000 people in the building at one time, and probably gets close to 500K a day, over three days. Here is a time-lapse video of the line one day at Comiket. Dawn arrives at about 1:25, so you can see the way the line is organized and Comiket opens at about 2:00.

People are shepherded into blocks; the blocks are moved forward around and through the plaza that surrounds Big Sight. People coming out of the Ariake train station are walked out and around/behind the Big Sight area, so as not to interfere with existing blocks. Even at peak waiting times, the blocks are moved efficiently – we have never waited more than about an hour to get in. Signage and volunteers move people efficiently and there is very little standing around aimlessly wondering why nothing is happening.

Line etiquette is important at Comiket, because most of what one does all day is walk, then stand in line. People attend Japanese comic events to buy comics and limited goods sold by the companies. If one wants to get official series goods, one has to line up on special lines that go to the corporate level – they begin on the side of Big Sight, not in the front. Blocks are moved in from those lines outside to stand in another line that winds its way up to the booth itself.

If one is not interested in the corporate booths (that is, there’s no rare goods one simply *must* have) then one walks up the stairs and into the front entrance:

When you come out of the tunnel, to the left are the East Halls and to the right are the West Halls.

The East Halls are like this:

There are two sets of three Halls, on one side are Halls 1-3 and the other have 4-6, each of which is Airplane hangar sized.

The West Halls are three sides around a square:

In the middle of the square is the escalator one takes to visit the Cosplay area, which is separated from the Halls, so one does not get beaned in the head by unwieldy props. At Comiket, there are specific rules around not coming to Big Sight dressed in costume, where changing rooms are located and what times attendees are allowed to cosplay.

These rules are only partially followed and one can often seen vendors coming in partial or full costume. The last year we saw more cosplay wandering around the halls than in previous years.

Also notable were the presence of people who talked in line. If you’ve ever attended a western event, you are used to the constant background level of noise that being around several thousand chattering enthusiasts create. For years, on a Comiket line – especially outside lines – it was so quiet you could hear the click of phone buttons texting. This last winter we were surrounded by people talking in line, and even saw a Comiket date or two. It was a nice slide into a less ordered world for Comiket; this addition of “social” to an otherwise seemingly solitary pursuit.

Comiket is not a “convention” in the way most fans think of it. It is a selling event, where 10,000 vendors park themselves for 6 hours in order to sell derivative, transformational and original comic works, DVDs, games, and other related media. People line up to purchase, and possibly to praise, to ask when the next collected volume comes out, if the artist is a pro, or to simply show support in the most universal way possible – by handing over money. At its heart, Comiket is about creation of work, and appreciation for that work.

Now, for the small – Yaoi and Yuri Con (YaYCon) was held in a music venue, Atak, in Enschede, The Netherlands.

There were two stages for events and the Dealer’s Room was a collection of tables in the lobby, while the Artists’ Alley was in the basement hallway. They screened some anime, but the focus was, as it so often is with western cons, participation. Cosplayers wander the halls freely, without the space/time limits of Comiket, often clumping in front of exits in response to some universal human behavior.

The Dealer’s Room is only as popular as the rarity of the items in it – people are more likely to invest money in discounted books or unusually difficult to find goods or, even better, in custom artwork from the Artists’ Alley, rather than just buy what manga or anime is for sale. Online shopping has changed the dynamic for buying anime and manga and streaming is whittling away at what is left of that. A savvy dealer brings what cannot be found elsewhere, or goes home with a lot of stock. Since doujinshi, small or self-published comics, often cannot be purchased online, events are the place to buy these, just as at Comiket. Dutch fans seem to be particularly motivated to create original works. Even at and event of this size, there were a number of groups creating original works.

Comiket does have some panels, but they are not the focus of the event. There are a few behind-the-scenes meetings, as well. Western cons, relying as they do on fan participation, spend more time on panels and workshops. At YaYCon I was invited to do a lecture on Yuri. The lecture was packed, which is to say about 30 people. But, would they get my lecture, full of Japanese terms, American slang and the occasional polysyllabic words? Oh, yeah, no problem – they laughed in all the right places. ^_^ We followed this up later with a panel of Yuri manga that is currently or soon to be available in multiple languages; English, French, German, Polish and Italian.

YaYCon presents itself not only as a Yaoi and Yuri convention, but a LGBTQ friendly space. The dynamic of the attendees were open to all representations of all sexuality, with none of the expected intolerance of other people’s fetishes one sometimes runs into at American conventions. This was a nice change of pace from conventions elsewhere.

Participation, financial support for creators, social events, artistic expo, exhibitionism, niche enthusiasm and a dash of “I know more than you about this series.” Anime and manga events are a messy stew of these elements.

Whether they are big or small, it’s clear that the chaos of creation and participation thins the line between fan participation and semi-professional employment in unique – and universal – ways.