Six miles away from my office is a theater that plays Bollywood movies simultaneously with their Indian release. This is one of them.

***

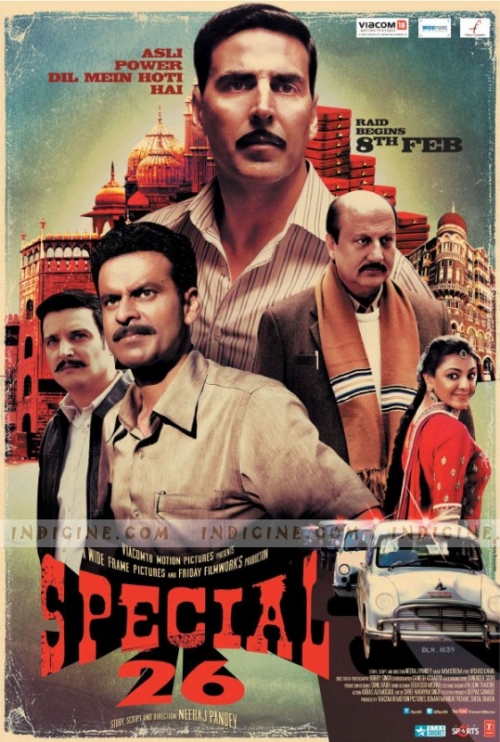

Special 26

Directed by Neeraj Pandey, 2013

***

*SPOILERS THROUGHOUT*

***

WHAT CAN WE GUESS THE FILM IS ABOUT FROM THE UNSUBTITLED TRAILER?

One initially expects the picture is about a revolution in chroma key backdrops overtaking India’s newsreaders, but this is quickly proven superficial. Some variation on “TRUE INCIDENTS” awaits, dear children, with the authoritative voice of Akshay Kumar barking “raid dalni” while clacking fonts assure us that shit will imminently get at least as real as Zero Dark Thirty. At least. Look at Anupam Kher slap that guy. I swear to god, I walk out of every Bollywood movie wanting to slap as many people as conceivably possible; no other world cinema tradition has so *totally sold* the virile crack of flesh on cheek. Mmm! Anyway, it looks like the Central Bureau of Investigation is raiding the hell out of major dudes, except REAL IS FAKE and vice versa, leading to at least one broadly satirical(?) speech on the value of patriotism delivered by a top-ish Hindi movie star in a crisp professional shirt. Action! And a little dancing!

***

WHAT IS THE HISTORY BEHIND THIS PICTURE?

Once upon a time, there was a boy from Punjab who grew up in the markets of Chandni Chowk and went to school in Delhi and Bombay, and then, apropos of apparently nothing beyond personal desire, relocated in his late teens to Bangkok to study martial arts, at which time he supported himself as a waiter and a chef. Upon returning to India as a martial arts instructor, he unexpectedly broke into modeling, and then, by chance, the cinema. “I’ve been linked with every heroine I’ve acted with,” he would later say, but this was only fitting: a gadabout reputation for a Bollywood outsider, a strapping naïf who would take what he wanted, when he wanted it, and saunter away whistling to the next big thing.

Most Bollywood heroes have legends, and this is the legend of Akshay Kumar, born Rajiv Hari Om Bhatia, active since 1991, and limited only — so the stereotype went — by his own whimsical ambitions. He would score lead roles, sometimes, and big hits, sometimes, but in the ’90s he was mainly associated with the B-grade arena of action pictures just a little ways past the vogue for those. He even had his own signature series of films: Khiladi, or “Player,” which did not hew strictly to action or suspense over the course of its eight feature-length installments, but that was where it always returned. Where Kumar, who did a little of everything, always returned. He was a ‘classic’ Bollywood workhorse, at one point appearing in a dozen feature films in one year, which by that time was very much not the behavior of a ‘major’ star.

Still, there are occasional benefits to prolificacy. In 2007, sixteen years into his career — having spent much of the decade oscillating between dubious action and romantic comedy with dips into outright drama — Kumar unexpectedly saw each and every one of his four releases hit hard, with three of them grossing over Rs 100 crore.

Suddenly, he could no longer be ignored as a periphery leading man, and gradually — be it through artistic desire or a sense that he could branch out into different areas of potential income — his risks became higher-profile.

In 2008, Kumar and his wife founded Hari Om Entertainment, a production company. Their first project, Singh is Kinng, betrayed a global outlook, with footage mostly shot in Australia, a plot remade from an ’80s Jackie Chan vehicle, and a closing credits cameo appearance by American rapper Snoop Dog. It was a financial success. The next year, Kumar seemed to double down with Chandni Chowk to China, an ambitious India/U.S. co-production with an autobiographical slant to its script. You’ve probably not heard of it, despite Warner Brothers ensuring distribution in North America; like all Bollywood/Hollywood team-ups, it seemed fated as marginalia on both sides of the globe. Interestingly, despite the seemingly personal nature of the project, Kumar managed to keep Hari Om out of the mess, though his brand nonetheless suffered; by the end of 2009 he had also co-starred in Blue, the most expensive film in Bollywood history (as of then), which also under-performed.

This prompted a particular type of conversation about Kumar, one which continues to this day: is he really a movie star? He *is* to some degree, of course — he’s the lead actor in an awful lot of movies — but his reliability as a ‘draw’ is more comparable to a Matt Damon or a George Clooney (the reduced ‘stars’ of high-concept, branding-mad America) than the Hero is Everything ethos still in strong effect in Hindi pop cinema.

The temptation, then, is to hypothesize Kumar as the potential herald of a less star-focused Bollywood, though a connoisseur might simply dub him a minor presence in the constellations. My own first encounter with his work came similarly troubled, through 2010’s wretched Action Replayy, an utterly risible fusion of Back to the Future and The Taming of the Shrew that nonetheless startled me by how completely fucking serious Kumar seemed to be taking the Crispin Glover role of a nerdy, put-upon dad, waves of shame and resentment all but jumping from his face for the first two reels of the picture. “What the hell is this guy doing?” I thought. “He’s not a terrific actor or anything, but he’s taking this dumb shit so… seriously.”

By the end of that year, my feelings had evolved in a typically perverse manner. Ask anyone — anyone — what they made of Kumar’s Christmas 2010 co-production, the notorious Tees Maar Khan, and they will instantly claim a career low for its leading man, and potentially the whole of 21st century Hindi film. It was moronic, it was insulting, it was ugly, and, worst of all, it was quite lucrative, due to intense hype, incessant advertising and a massively front-loaded opening weekend, nimbly avoiding the word of mouth that would eventually win the film a 2.5 rating on the IMDB, one of the lowest from Bollywood-acclimated users.

I rather like Tees Maar Khan. It’s the bitterest movie in the entire world, and damn fascinating as a moment capture. Directed by Farah Khan — an acclaimed dance choreographer, media personality and probably the only woman in India who could realistically call herself a superstar filmmaker — and written & edited by her husband, industry gadfly Shirish Kunder, the film is uniquely positioned as a peek into a private world of politics, resentments, and general beefs.

Adapted from Vittorio De Sica’s 1966 Peter Sellers outing After the Fox, the plot finds Kumar as a legendary con man, who, cognizant of the bottomless hunger Indian cinema types have for Western approval, poses as M. Night Shyamalan’s lighter-skinned brother and hooks up with a pretentious film hero driven Oscar-crazy in the wake of Slumdog Millionaire. An absolutely vicious parody of megastar social crusader and ‘quality’ Bollywood icon Aamir Khan (with more than a dollop of Shah Rukh Khan plopped on top), the delusional actor is more than willing to participate in BIG-TIME HOLLYWOOD PROJECT — amusingly pitched as a paean to Indian suffering, i.e. the only way to get Americans to acknowledge anybody outside of the first world — which is actually just an excuse for ‘director’ Kumar to rob a train right under the noses of ignorant, starry-eyed village folk.

The true objective, of course, is to broadcast Khan’s & Kunder’s unflagging sneer at everything in show business that irritates them, including but not limited to Hollywood influence, cultural tourism, bucolic ‘patriotism’ and the current crop of heroines — poor Katrina Kaif seems to have been cast as the female lead specifically so Khan can make fun of her; despite being a romantic interest, Kumar never shows her the slightest affection outside of the obligatory song sequences, which is a bit of parody all its own — not to mention critics, audiences, and indeed, the very notion of cinema ‘art.’ To Khan, through her onscreen avatar, film direction is revealed as a con game, useful primarily for facilitating a properly modern Indian lifestyle — rightly separated from the laughable grotesquery of dirt-eating village life but proudly self-reliant and anti-American in its urbanity — with the happy accident of people sometimes finding themselves entertained in the process of being used, the stupid fuckers.

Taken in this way, Tees Maar Khan is a genuinely radical (if gigantically obnoxious) work of thematics, totally unafraid of seeming shrill or hysterical or any of the other gendered insults you can throw at a woman behind the camera. Employing an ultra-high camp mise-en-scène recalling late ’90s Old Navy commercials, its soundtrack prone to screeching “TEEES MAAR KHAAAN” at every instance of on-camera mugging, the film all but dares you to hate it, to get up and walk away from its brazen irritations; such provocation is a very rare thing in eager-to-please Bollywood, especially coming from as otherwise easygoing and cosmopolitan a guy as Akshay Kumar, who must have felt weird as hell seeing the results. He nonetheless teamed with Khan & Kunder again for a 2012 directorial project by the latter, an eccentric children’s film titled Joker that proved so unpleasant a process Kumar abandoned promotions for his own co-production and left it to die a dog’s death in theaters.

Yet given the latitude of perspective, it’s easy to see why Kumar would click with the surface attributes of such filmmaking. His style of delivery hews toward the very broad and loud, to the point where anything resembling a subdued performance inspires a Jim Carrey-like overcompensating toast to fresh-blazed subtleties. He is also that special kind of macho male whose classical masculinity is so little in doubt he’s become fond and unafraid of strutting around in pink and incorporating effeminate, almost coquettish overtures into his presentation.

You can see why a Farah Khan would find him camp as fuck, though Kumar’s tiny resistance to heteronormative standards may betray a deeper sympathy; while Tees Maar Khan adopted the I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry approach of cracking gay jokes as a means of normalizing homosexual relationships, one of the songs in Kumar’s 2011 Canada-set co-production Thank You matter-of-factly depicts one man slinging his arm over another, flowers in hand, while the star producer gazes on in approval. Similarly, the skin color jokes of Tees Maar Khan are refracted in Kumar’s 2012 neo-masala romp Khiladi 786, which posits Kumar’s hero cop and a brown(er)-face doppelganger brother as scions of a wildly mixed-race family, the earthy harmony of which is stereotypically but earnestly emphasized.

Perhaps most startlingly, Kumar has recently set up a second production house, Grazing Goat Pictures, for the purposes of exploring ‘quality’ films. Its virgin feature effort was 2012’s OMG – Oh My God!, an adaptation of a popular stage play Kumar credited with inspiring a profound change in his religious practice. A riff of sorts on the 1977 George Burns starrer Oh, God!, the film maintains the pose of a light comedy, but also directly tackles the industry of diverse religion in India in an unusually thorough manner. More than anything else, it’s been the critical and popular success of this film that has threatened to completely revise Kumar’s reputation – suddenly, he is “mass” and “class” alike, and uniquely equipped to push Hindi pop movies into less-comfortable places. Or so is the wish.

***

WHAT HAPPENS BEFORE THE INTERVAL?

Immediately, we are confronted with a most patriotic illusion, as a serious young woman delivers a speech detailing the idealistic motive behind her applying for a job with India’s Central Bureau of Investigation (“CBI”). Visible on the margins are her interviewers — Akshay Kumar and veteran character actor Anupam Kher — who, if you have done any research whatsoever prior to seeing the film, are evidently not real CBI officers, though they maintain classically straight faces throughout the process. Soon, we are seeing footage of an authentic 1980s Republic Day parade; this is both to establish the time period of the film, as well as writer/director Neeraj Pandey’s satiric theme. Unique from India’s Independence Day (which celebrates liberation from British rule), Republic Day commemorates the adoption of India’s first Constitution, thus placing its focus on the stability of a federal apparatus that still employs the CBI as its primary criminal investigation body.

Naturally, it’s all bullshit. Particularly since the 1970s — a great era of social entertainments pitting angry young men like Amitabh Bachchan up against an uncaring society toxic with corrupt administration, self-serving capitalism and ruined idealism — ‘adult’-oriented Bollywood films have been massively skeptical of the efficacy of business and law enforcement powers; rare is the public works official not hungry for kickbacks, or the titan of industry not sleeping on black money, or the policeman not toadying for regional dictators. If there’s elections that aren’t rigged, I haven’t seen ’em. Even the brazenly reactionary neo-masala wave, escapist as it is, typically frames its swaggering, mustached hero cops as aberrations: forces that defy the will of the majority and the laughable ruse that is the ‘rule of law’ to bring immediate, popular justice to the displaced and needy.

Pandey is working loosely from a true story in Special 26 — a 1987 incident in which fake CBI officers robbed a Bombay jeweler under the auspices of an official raid — but his deployment of a ‘period’ setting also (inexactly) evokes an older era of Hindi film for its gloss of righteous criticism. Indeed, for the first fifteen or so minutes of his film, Pandey strings the less studied viewer along by presenting Kumar & Kher and their gang of loveable cronies as *actual* CBI officers, prepping for and carrying out a tax raid on a local politician. Basically — in movie terms! — that means CBI officials get to burst in on somebody’s home or place of business on suspicion of tax evasion, literally tearing apart the walls searching for money the suspect has inevitably stashed in huge clumps somewhere on their property. “You will be cursed!” shouts a woman as the men move a religious icon from its place of rest, complacent as everything else in a shit society.

It’s all quite exciting; Pandey hails from the world of television commercials and documentary film, having only made his theatrical feature debut in 2008 with A Wednesday!, a Hollywood-sleek hour-and-forty-minute tour of a day in the life of a police commissioner (Kher again) who must negotiate a mysterious terrorist threat. Special 26 is his sophomore feature, likewise effective at caffinating legal procedure – witness Akshay Kumar, clad in a crisp, Rick Santorum-worthy sweater vest ensemble, wriggling his ‘stache while knocking on walls, cracking the dirty politician’s private property like it’s a bank safe! And what a slap Anupam Kher delivers when the suspect hazards a bribe!

Perhaps the seasoned viewer can’t possibly believe such upstanding civil servants could really exist; when Kher delivers a snappy catch phrase to a goggle-eyed young policeman about the importance of Heart, it’s a self-evidently filmi moment, dreamed up on the fly by a man who has doubtlessly crafted his con man persona from long hours in the theater, all the better to fool higher-paying rubes. Perhaps this charade of idealism is merely Pandey’s shaggy dog way of setting up a joke, the punchline arriving when Akshay Kumar — handsome here like a old American matinee idol — tears off his facial hair as the team makes its getaway.

But Special 26 is also cognizant of audience expectations on a less confrontational level. At two hours and twenty-three minutes, this is a far longer film than A Wednesday!, and Pandey spends much of the first half detailing the circumstances that have led Kumar & Kher into their situation. The latter is not a stern authority figure at all, but a comical neurotic — such an ability to convincingly switch between ‘funny’ and ‘serious’ personae has made Kher one of the very few Bollywood lifers to occasionally pop up in English-language films, such as David O. Russell’s The Silver Linings Playbook — who needs a lot of extra money to support his gigantic family, while Kumar is just a roguish romantic who hopes to earn enough scratch to spirit his girlfriend away from her unhappily looming arranged marriage.

As we eventually discover, Kumar was once a CBI prospect who was rejected for service due to his lack of skill with English (a neutral, ‘universal’ language); as a result, his obsessive knowledge of federal procedure empowers him to throw India’s would-be national outlook back in its rotten, corrupt face… anyone prominent can be targeted for a fake raid, after all, because everyone is corrupt. If director Pandey notices that such all-devouring cynicism is just as much a movie device as goody platitudes, he doesn’t let on, perhaps embracing this cooler brand of artifice in the same manner a masala director might crank out the fights and dances.

There are dances in here, though. Ha ha.

You’ll notice I didn’t identify the girlfriend just above. Sadly, that’s because actress Kajal Aggarwal (mostly of Telugu and Tamil ‘south’ film) is saddled with one of the most thankless, do-nothing roles in recent memory, stranded amidst a romantic subplot that eats up an extraordinary amount of screen time without accomplishing anything beyond the most banal platitudes. Obviously, such problems are not unique to Bollywood. Were this a Hollywood film, I’d theorize that some studio executive had delivered a note reading “MAKE AKSHAY SYMPATHETIC, XOXO” but it seems likely here that the romance takes up so much space to facilitate adequate song tie-in monies for somebody’s corporate partner somewhere. I don’t mind when a Hindi action movie breaks into song and dance — you just buy into that possibility coming in — but the music of Special 23, set to ‘missing you‘ montages and the like, works at direct cross-purposes with the suspenseful, relentless, immersive pace Pandey obviously seeks to build. A ‘traditional’ Bollywood movie is so often a work of vignettes – a modular evening of courses. This is like eating a piece of a steak, and then waiting a while for the second piece to be brought out, and then the next, and the next.

But then, that is the balance when you seek to go big. Akshay Kumar may be a modest progressive, but knowing that he *can* pull off such things carries with it the burden of popular expectations that facilitate that very freedom, particularly when he’s not in control of the production. The public expects a sympathetic, heroic figure, and Special 26 is altogether eager to play up Kumar’s movie star reputation as much as his offbeat tendencies. The result is really a hybrid film, but not something that benefits from hybridization: so eager to provide a slick, straightforward work of suspense and critique, Pandey winds up seeming less sure with the songs or the romance than any of the ’70s and ’80s social picture forebears he plays at emulating. Like Kumar, he is man slightly astride his transitional age.

***

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER THE INTERVAL?

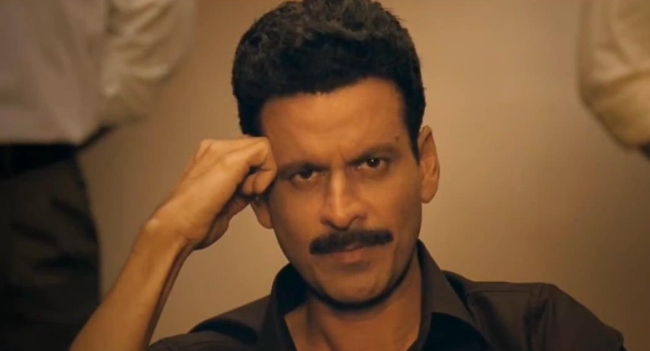

The second half of the film primarily concerns the climatic jewelry heist, as well as a cat-and-mouse game played between Kumar/Kher and and actual CBI investigator played by the always-excellent Manoj Bajpai, whom nobody will call a traditional movie star, though he embodies a more intense tradition than Akshay Kumar.

A television actor who made his film debut in 1994 via future (and temporary) Oscar semi-darling Shekhar Kapur’s Bandit Queen, Bajpai rose to prominence in 1998’s Satya, one of the landmark works of contemporary alternative Hindi pop cinema – not exactly the ‘parallel cinema’ of art film, but a distinctly vérité, rough-hewed, criminally-focused brand of urban fiction. The director of the film was Ram Gopal Varma, a prickly, erratic, sometimes rather goofy figure deserving of more attention than I can afford right now, though it’s sufficient for these purposes to note that he’s often sought new and potentially unpleasant ways to produce ostensibly popular films, including recent forays into (unwatchable) microbudget filming and (slightly underrated) consumer-grade digital photography, recently given way to large-format tragic docudrama.

Even more pertinent, though, is the co-writer of Satya, one Anurag Kashyap – more than anyone else, Kashyap embodies the present counter-mainstream in Bollywood, perhaps because his films often strike an explicitly critical stance against the Hindi film norm. His 2007 feature directorial debut, Black Friday, despite its stance as (another) tragic docudrama, was both a sensitive investigation of the heroic/villainous police dichotomy and an avowed cinematographic influence on Slumdog Millionare, while his 2009 Dev.D mined intriguing veins of misogyny and self-abuse from the beloved, oft-filmed Bengali novel Devdas.

Bajpai reunited with Kashyap for his most recent directorial pursuit, 2012’s weird, beguiling, tiring, indulgent, and undeniably 5 1/2 hour-long Gangs of Wasseypur. Eventually split into two films for ease of release, the project was a shoot-for-the-moon attempt at a century-spanning, multi-generational crime saga comparable to The Godfather and its sequels; while the results frankly suggest less of a novelistic immersion than a filmmaker simply unwilling to edit much of anything, Gangs of Wasseypur nonetheless boasts a commanding, impulsive performance by Bajpai (and an equally good Nawazuddin Siddiqui), and an all-time high for the agony of influence active in Kashyap’s cinema, climaxing in an agonizingly long, unbroken shot of a wounded man crawling through a house in flight from assassins, the soundtrack humming his very favorite cheesy Bollywood romance song to give him strength, to fortify his misguided character, to affirm his misspent life.

Where Kashyap is agonized, Pandey is content. He establishes Bajpai a bit prior to the interval, in an extended chase scene that serves mainly to give him something ‘active’ to do in a screenplay that might otherwise leave the audience unstimulated for a millisecond. Egged on by the aforementioned goggle-eyed (now seemingly humiliated) young policeman from the prior raid, Bajpai muscles his way into the jewelry plot, which centers around Kumar & Kher recruiting a cadre of underemployed dumbass civilians to serve as an unwitting backing army in the raid. They are not quite the “Special 26” of the title, however, as Kumar & Kher are (of course!) playing a long con, and (of course!) the goggle-eyed cop was a deep-cover plant, in on the scheme the whole while, and (of course!) our anti-heroes have prepared for every eventually, ultimately using the real CBI as an inadvertent decoy while the real raid goes down with triumphant slow motion punctuation at a different locale.

Yet where does this leave us? One might assume that Pandey is making a point about capitalism — there’s a classically cheesy humanizing moment near the end where Kumar mails Bajpai back some money he snatched from him earlier, ’cause he don’t steal shit from honest working men — but the only real success his heroes enjoy is their entry into a more relaxed social strata. Indeed, they mostly take advantage of their fellow proles in the process, without a lot of regret, if never exactly to their material detriment. Maybe Kumar hasn’t wandered so far from Tees Maar Khan after all. Maybe this is all nothing more than a writer/director applying all sorts of domestic mainstream gloss to his foreign mainstream influences, and happily cashing in – Special 26 is already the second-highest grosser of 2013, standing at about Rs. 65 crore, having done enormously well for an ‘small’ film.

Still, there is a weird ambiguity at the end of the picture, as the frustrated Bajpai suddenly receives a new lead on the whereabouts of the thieves, just before the end credits. Did censorship concerns prompt a crime (sorta) doesn’t pay (maybe) denouement? Or did Pandey mean to suggest that, having become rich in place where rich equals corrupt, his heroes will inevitably become corrupt as well, and require toppling? Endless conflicts like that can power endless, profitable, probably banal fictions, though the success of this one again inspires hope for another small line of credit extended to Akshay Kumar, another possibility for another small step for this Bollywood outsider, wormed goodly inward and now slowly navigating his way out.