This first ran on Splice Today.

——————-

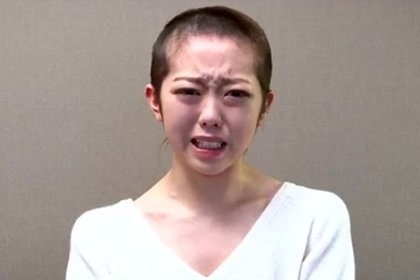

Japanese pop star Minami Minegishi, member of the pop-band-cum-walking-reality-show AKB48 was caught leaving the home of Alan Shirahama, a member of the boy-band Generations. In the US this would be gossip fodder and a boost for both their careers. In Japan, though, it was a scandal—Minegishi had signed a contract promising not to date, and the apparent tryst with Shirahama violated her agreement with management. Facing the prospect of being kicked out of the band, Minegishi recorded a video for the band’s official channel in which she tearfully begged to be forgiven… and explained that she had shaved her head in penance. (The official video seems to have been taken down, but a sample is here.)

As I noted above, AKB48 is not just a band; it’s a kind of American Idol reality-show performance-art extravaganza, with 88 members, different teams, and a cast of aspiring wannabe singers. Fans are encouraged to follow individual performers as they try to get into the band and then move up the ranks, eventually graduating as they get older.

The performers are banned from dating because having boyfriends would interfere with the fantasy of virginal purity and availability which drives the male fan investment. In this context, Minegishi’s tearful apology is itself a packaged dramatic moment in the band’s marketing; the singer’s deference and pain are, and are meant to be, consumable entertainment. Which in no way means that her tears or desperation aren’t real, it just means that real tears are extremely valuable to her employer. It’s possible that the management miscalculated somewhat on the extent of the international push back, or, perhaps not. Scandal is rarely bad for business.

All of this is fucked up, as Ian Martin points out in an excellent article for the Japan Times. Different cultures are different, and I’m as wishy-washy as the next liberal relativist, but still. Forcing young women into the closet and then raking in money based on their emotional distress is evil, whether it happens next door or overseas.

In this case it did happen overseas, and it’s hard not to in part react by saying, “Those Japanese are crazy!” There’s certainly something to that—the individual giving up her rights to the collective, and the ritual apology both seem quintessentially Japanese. It’s impossible to imagine even a pre-fab pop star like Justin Timberlake or Britney doing anything like this, not least because their images and marketing are partially based on rebelliousness.

Still, if mores are not the same in the US, the underlying dynamic is perhaps not necessarily quite different enough from comfort. I’m thinking of Ann Wilson, the force-of-nature vocalist for the 1970s rock band Heart. Wilson was allowed to date—the hit song “Magic Man” is about her then-relationship with band manager Michael Fisher. Nor was she not a contractual employee of her band. And her appeal to fans was not her virginal fantasy persona, but her amazing singing.

Or so you’d think. And yet, over the course of Heart’s career in the late 70s and 80s, Wilson started to gain weight. As the VH1 “Behind the Music” episode makes clear, this became a serious problem. Music critics were vicious, incessantly focusing on Wilson’s appearance rather than on her phenomenal singing. The band’s label was just as bad. They harassed Wilson constantly… and tried to cover up her weight in videos by piling her hair higher and higher and by focusing more and more obsessively on sister and Heart guitarist Nancy Wilson’s breasts.

In the “BTM” episode, Nancy notes that the management kept saying that if Ann would lose weight they would make more money, which was kind of ridiculous since they all were, as Nancy said, making plenty of money. Similarly, it’s difficult to believe that AKB48 would actually stop being successful if it allowed its performers to date. The issue, then, seems like it’s less dollars per se than a kind of ideological capitalist rage for totalizing commodification. The product must be the product; the product shall be the product; that’s the logic of the market, and if there’s some human over there with desires or a body, then that human needs to be erased.

Sometimes the erased humans in question can be male… but women, in our society and in others, are more enthusiastically objectified than men. Thus, in Japan, Minegishi’s boy-band boyfriend didn’t face any repercussions for having a girlfriend. And in America, there’s Meatloaf. Guys aren’t expected to be fantasies, or products, the way women are in Japan, or were in the 1970s—and the way they still are, in many ways, in the US today. In that sense, Minegishi’s video doesn’t seem odd or foreign at all. On the contrary, it seems quite, depressingly, familiar.