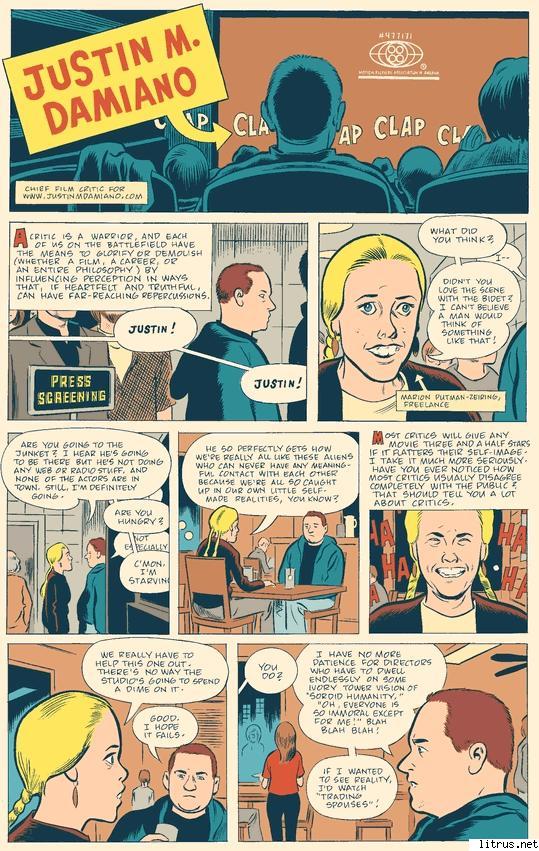

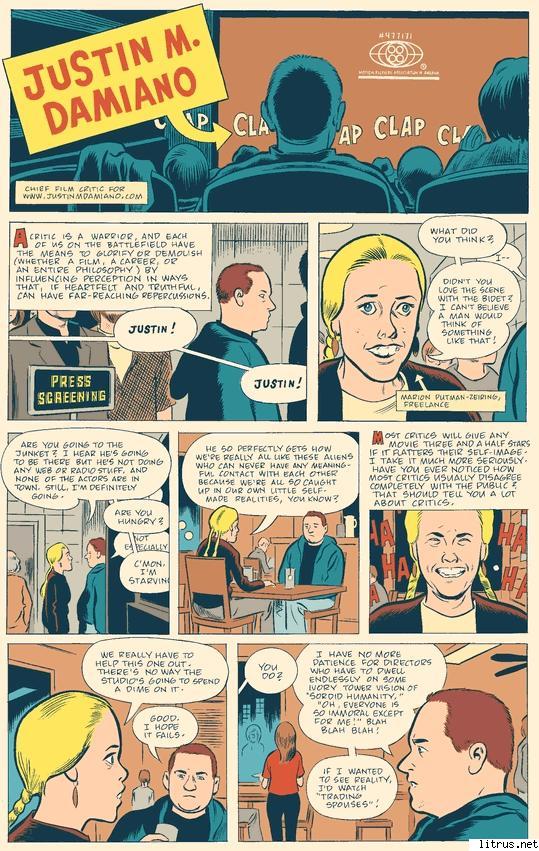

Justin M. Damiano was first published to limited notice in The Book of Other People (ed. Zadie Smith; full comic at link) in 2007. Its existence was jogged back into my memory by James Romberger’s recent review of The Daniel Clowes Reader where he calls it:

“…a classic that needs to be read by anyone who writes criticism on the internet.”

This wasn’t the way I remembered the story and I read it again to see if I had been blinded to its treasures on my first read through.

A number of critics have taken Justin Damiano to their bosoms, elevating the specific into a judgement of the whole or at least a comment on a significant number of online critics. At The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw suggests that:

“…mature, contemporary Damiano isn’t a cynic or a loser: he has transferred his idealism from the world of relationships to that of the cinema, and being an online critic, answerable only to himself, he is perhaps freer to express this pure, unapologetic idealism…Is Justin a sad sack for believing that this transcendence is to be found in the cinema rather than human relationships? Maybe – but not necessarily, and it isn’t clear that Clowes is inviting us to assume this.”

Another critic, Brian Warmoth, opines that:

“Clowes’ ability to distill the bitter side of humanity in menial activities and everyday labor or interests is extremely keen…It’s also about the rifts between critics and artists that can sometimes encompass shared ground.”

Part of this boils down to a presumption of antagonism—that artists are supposed to have a very low opinion of critics and criticism in general. It is easy to slip into this diagnosis unless one looks closely at the details of Clowes’ exposition, most of which holds very little water and specificity for critics. To suggest that Clowes was presenting a critique of critics in general here would be to do him a disservice and may even imply that he is a person of shallow intellect. Naturally the title of the anthology begs the question, “What other people?” It might be that the ultimate “other” for an artist is not his audience but his critics, but this wouldn’t be that much of a leap of the imagination for Clowes who has engaged in scathing criticism for years in the pages of his comics. Clowes isn’t so much an artist chastising critics but a practicing critic contemplating his own art.

Taking James’ premise as true, however, what exactly are the lessons we (as online critics, silent or otherwise) are supposed to glean from Justin M. Damiano?

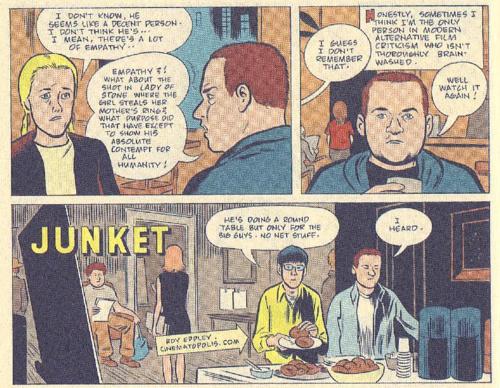

(1) Critics have a overweening sense of self-worth.

Translation for comics-kind: A comics critic is a (part time) warrior, and each of us on the battlefield have the means to glorify or destroy (whether a comic, a career, or an entire philosophy) by influencing perception in ways that, if heartfelt and truthful, can have far reaching repercussions.

This sounds insightful (and damning) until you start replacing the word “critic” with other words like, “artist”, “cartoonist”, “director”, “journalist”, “politician”, and “pop star”. Basically anybody with access to the wider media through talent, money, or both. In this day and age, this would mean a television program, a newspaper, a studio, and, yes, a popular blog. There is very little doubt though that the comics critic is the dung beetle of this august list of movers and shakers.

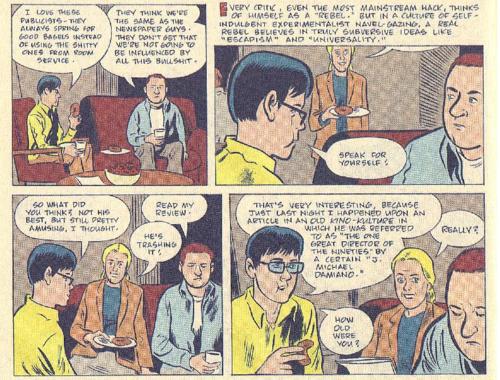

(2) Critics enjoy toilet humor (or perhaps playful metaphors).

Well, they sort of do, and they’ve also shown some fondness for bidets apparently. A clear reference to Duchamp and his porcelain urinal but also a self-referential finger pointed at Clowes himself—a very arch critic in many stories in Eightball and a florid user of metaphor.

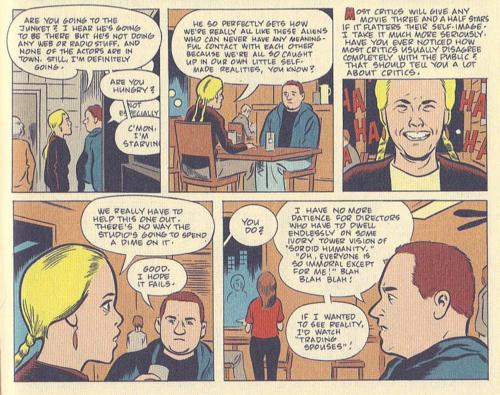

(3) Critics are self-absorbed and insular.

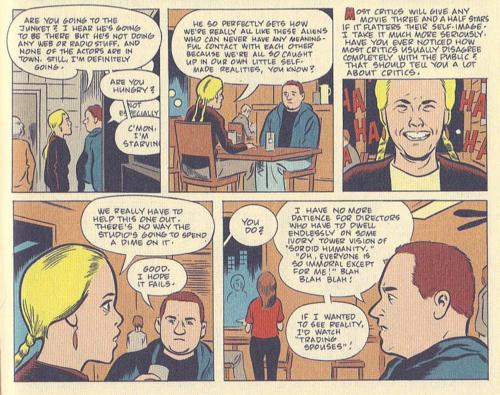

“He so perfectly gets how we’re really all like these aliens who can never have any meaningful contact with each other because we’re all so caught up in our own little self-made realities, you know?”

There’s an interplay between panels 2 and 3 on this page. The blonde girl, Marion, is the target of Justin’s irritable internal musings:

“Most critics will give any movie three and a half stars if it flatters their self-image…Have you noticed that most critics usually disagree completely with the public? That should tell you a lot about critics.” [emphasis mine]

That latter point is quite contrary to experience as a simple survey of the top 5 movies of the last two years will attest:

Top 5 movies by domestic gross 2013 with Rotten Tomatoes (RT) score

Iron Man 3 (RT 78%)

Despicable Me 2 (RT 76%)

Man of Steel (RT 56%)

Monsters University (RT 78%)

Fast and Furious 6 (RT 69%)

Top 5 movies by domestic gross 2012

Marvel’s The Avengers (RT 92%)

The Dark Knight Rises (RT 87%)

The Hunger Games (RT 84%)

Skyfall (RT 92%)

The Hobbit (RT 65%)

Of course Clowes doesn’t mean any old critic. He means critics like Justin M. Damiano who is shown throughout this page in an act of self-condemnation, hurling stones at others while he sits in his own ivory tower of arrogance and recalcitrant elitism—the stuck-up loner with delusions of grandeur; the keyboard warrior of “modern alternative film criticism.” For all intents and purposes, this would include well over 50% of all comics critics.

But what exactly does “flatters their self-image” mean? One presumes that it means that critics tend to prefer movies which align with their own vision and experience of existence. Damiano suggests that critics should instead acquire a taste for other aspects of humanity as presented on film—those which run counter to their own beliefs. It should be stressed that we are specifically talking about “taste” and not action here, for Damiano is never shown acting on his preferences in art. Thus a critic with Randian principles should be able to develop empathy for the works of Vittorio De Sica. Similarly, a critic who abhors violence and misogyny should be able to appreciate and enjoy glorifications of the same. Since Marion is portrayed as a typical online critic, some might see this a proposition put forward by Clowes but this may not be the case. If Damiano is seen as a negative indicator (in some instances), it could also be taken as an admonishment of the critical community as a whole.

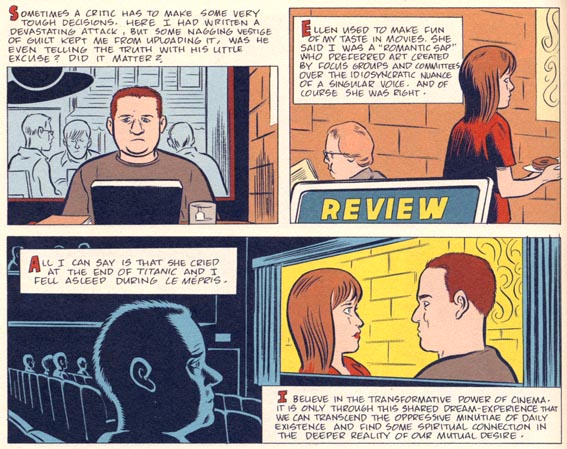

Marion’s comment that the film depicts human as “aliens who can never have any meaningful contact with each other” proves to be Damiano’s own “defect”—the very reason why he prefers “escapism” in film. The cinema becomes a brothel of whispered dreams and vicarious experience, a panacea for his lack of human contact. This explains his boredom when faced with Godard’s Le Mepris (a film about estrangement), a movie which probably mirrors all too accurately his own life. This isn’t so much Clowes needling critics so much as Clowes poking fun at himself, for his comics have consistently portrayed “sordid humanity” and immorality.

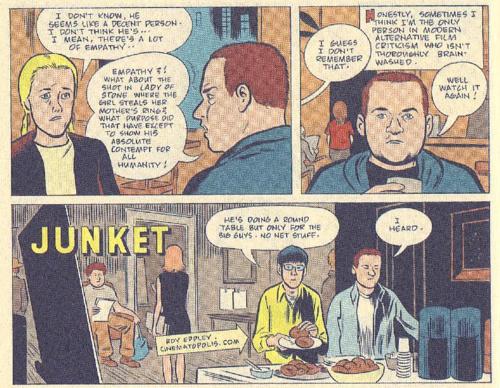

(4) Critics are mercurial and careless – “Good I hope it fails.”

But are they significantly more so compared to the general public?

(5) They don’t suffer fools gladly – “Well watch it again!”

(6) They are frequently jealous of access.

See point 4.

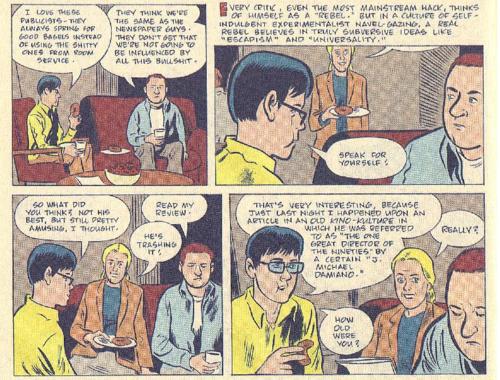

(7) “Every critic, even the most most mainstream hack, thinks of himself as a “rebel.” But in a culture of self-indulgent experimentalist navel-gazing, a real rebel believes in truly subversive ideas like “escapism” and “universality.”

This isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. Damiano suggests that every critic considers himself a “rebel,” which would make him a rebel himself. Rather than promoting “bidet” art, Justin has taken his beliefs one step further and is rebelling against rebellion—championing “escapism” and “universality.” In other words, the act of criticism is seen here not so much as an act of connoisseurship but a process of self-promotion and self-aggrandizement which has little relation to “taste” or the object beheld.

At this point, alternative comics criticism and film criticism diverge, at least in the American sphere. The gradual migration of superhero fans into alternative comics has led to a renewed interest in objects of times past and the assimilation of tropes and techniques associated with superhero comics and other forms of commercial art. Further, this might be an area where comics have a leg-up according to Justin Damiano’s injunction. The 5 nominees for Best Continuing Series at the 2013 Will Eisner Awards were Fatale, Hawkeye, The Manhattan Projects, Prophet, and Saga—all firmly lodged in the realm of of “escapism.”

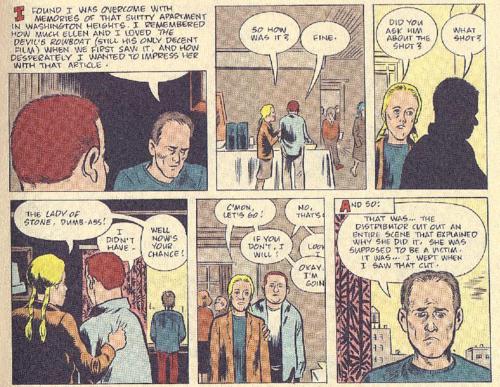

(8) Criticism is autobiographical and self-revelatory.

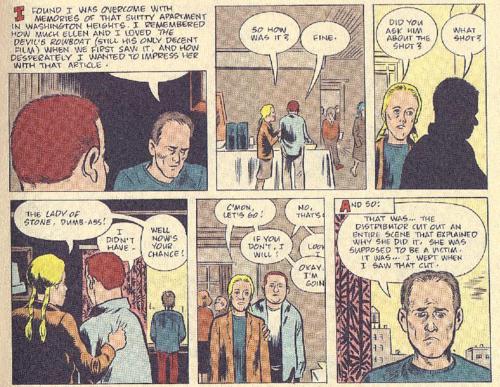

“I remembered how much Ellen and I love The Devil’s Rowboat…and how desperately I wanted to impress her with that article.”

In the first panel of this page, Damiano’s thoughts completely obscure the words of the director who bears a vague resemblance to a balding Clowes (well, it could also be Gary Groth). One might say that his own thoughts take precedence over the ideas of the director being interviewed; a point further emphasized by the revelation that a favorite scene of his from an earlier film of that director was quite unintentional (the result of a distributor cut).

This seems like a knock on critics but it actually suggests that criticism is as much an act of creativity as the production of a film or comic—a metatextual comment on the object being read. The real mark of bad criticism in my view is “objective” synopsis. I wouldn’t read criticism if it all read as if it was produced by a machine (or a marketing agent).

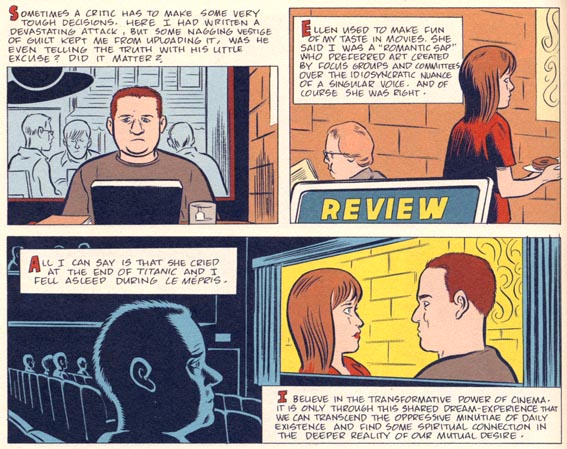

(9) Critics are frequently loners with poor social skills.

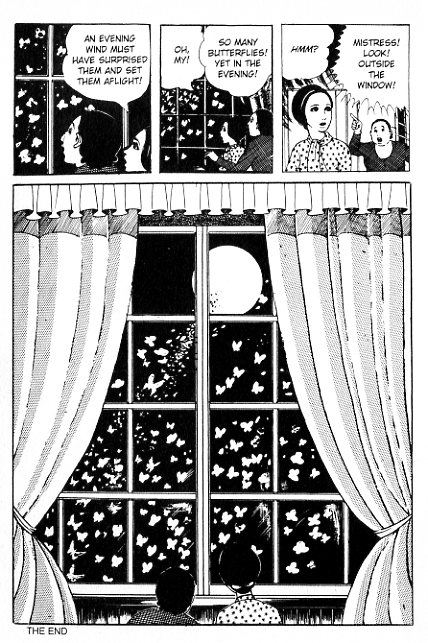

“I believe in the transformative power cinema. It is only through this shared dream-experience that we can transcend the oppressive minutiae of daily existence and find some spiritual connection in the deeper reality of our mutual desire.”

Justin is looking at a pictorial representation of a cinema screen which is actually the fourth panel of the comics page. This is probably a reference to Clowes’ own migration to and from comics and film.

Clowes’ cynicism is so thoroughly ingrained into his comics that the somewhat ambiguous but treacly conviction stated here would quickly arouse the suspicions of his long time readers. One imagines that some people feel the same way about the films they see, but this seems like a specific interjection clarifying the state of mind of our protagonist, a point reasserted on the page following where he thinks:

“When Ellen finally left, she said she felt as though she didn’t even know me. She said I lived entirely inside my own head.”

The escapism which Justin seeks in the cinema (and art) has become a substitute for any real real connection. Any warmth in expression (the bottom panel bears his least contemptuous face) or speech is reserved for the figures he sees on the cinema screen. He has nothing but distaste for the people he interacts with in the pages of this comic.

It seems to me that whatever observations Clowes makes about critics are simply a side effect of using a film critic as the main character of his story. Any bitterness or acute observation is restricted to the first half of the story and forms the bedrock for his elaboration on the protagonist later in the tale. The further one delves into Justin M. Damiano, the less it reads like a standard exposè on the failing of critics, and the more it feels like a story about a man who just happens to be a film critic. In this way, it has many similarities to one of Clowes’ earlier works, “Caricature”, which constantly straddles the line between reality and illusion in its portrayal of a caricaturist—a competent loner working the crowd and his sexual proclivities.

But even more than in that work, Justin M. Damiano turns in on itself, becoming a moment of self-criticism and reflection; a careful dissection of his own comics. The “other” of the collection’s title (The Book of Other People) is not so much his critics or his audience—they remain anonymous and unknowable. The “other” is the person that he can never hope to become.