This is a slightly revised version of a piece that originally appeared on The Middle Spaces.

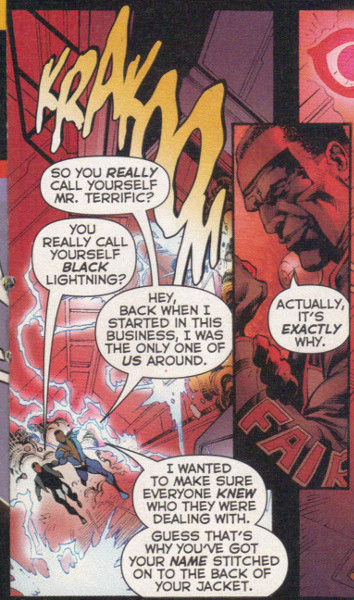

At the end of my overview of the five sad issues of Marvel’s Black Goliath, I mentioned that I was interested in spending some time with DC’s Black Lightning, so I made a point of seeking out its abbreviated 11-issue 1977-78 run and then was lucky enough to find the first five issues of the 1995 run at Half-Price Books for three bucks. As one of the commenters on that Black Goliath post mentioned, the Black Lightning run is superior to Marvel’s attempt to give another black character his own title, but at least Marvel had made two attempts, Luke Cage – Hero for Hire in 1972 and Black Goliath in 1976, before DC had even tried its first. In addition, those five issues of Black Goliath set the bar very low. It would be difficult to not improve on it, especially since the same creator, Tony Isabella was responsible for both. First of all, unlike Black Goliath, Black Lightning is his own character from name on—that is, he is lightning that is black (with a cool catchphrase, “Black lightning always strikes twice. . .” which references his penchant to follow up on problems in his community), not just a black version of an existing (or previously existing) character, like Henry Pym’s cast off Goliath (and later Giant-Man) identity. Secondly, Black Lightning focuses on a black community in DC comic’s iconic city of Metropolis that for the most part has been ignored, and mostly by Superman who calls Metropolis home. Jefferson Pierce is a kind of hero in his civilian life as well, having returned to where he grew up to be a high school teacher in a needy district, after having found success as an Olympic athlete and a having earned English and teaching degrees in college. Lastly, what I like about it—though there is also where it starts to enter problematic territory—is that Jefferson Pierce’s “blackness” is explored in relation to his superheroic identity. I find the problematic racial naming of Bronze Age characters somewhat mitigated if race is actually explored in their narratives, rather than the name being allowed to stand on its own as a kind of monolith of meaning. Geoff Johns made a point of bringing it up as recently as 2006 in Infinite Crisis #5, when Black Lightning is on a mission with another black character, Mr. Terrific. Lightning says by way of explaining his name, “Hey, back when I started in this business I was the only one of us around. I wanted to make sure everyone knew who they were dealing with.”

All that being said, it is still not a very good comic. Sure, it could have been worse. With a name like Suicide Slum they could have made Black Lightning come off like “Ghetto Man” from NBC’s Superfriends-like “Legend of the Superheroes” in 1979, but whatever promise was present in its setting and exploration of racial politics of superhero genre remains untapped. Almost immediately, Black Lightning’s narrative is mixed up with the baroque continuity of things like the League of Assassins (with an appearance by Talia Al Ghul in issue #2) and Jimmy Olsen shows up a few times, as does Superman—not sounding very Superman-like (not sure if that is sign of how Superman was being written at the time or a sign of Tony Isabella’s writing). The only interesting part of Black Lighting’s battle against street level crime is that his main opposition is this bizarre figure called Tobias Whale. Tobias Whale is drawn to emulate his name, inhumanly white, swollen, shapeless as if meant to echo Ishmael’s sentiments about Moby Dick expressed in Chapter 42 of Melville’s unrivaled novel.

Aside from those more obvious considerations touching Moby Dick, which could not but occasionally awaken in any man’s soul some alarm, there was another thought, or rather vague, nameless horror concerning him, which at times by its intensity completely overpowered all the rest; and yet so mystical and well nigh ineffable was it, that I almost despair of putting it in a comprehensible form. It was the whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled me.

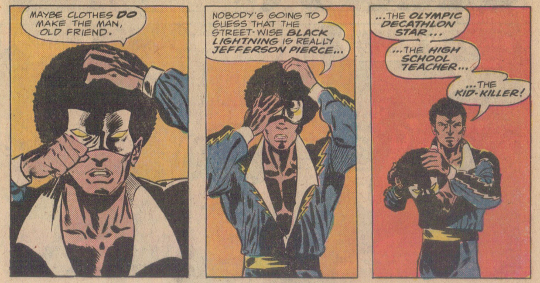

The reference may not be explicit, but I love the idea of an African-American superhero struggling against that kind of ineffable whiteness that pens in possibilities for individuals and communities. But that’s all there is here: ideas. While I can find lots of compelling possibilities in this comics, not one is developed, implicitly or explicitly. Foremost of these for me is that when Jefferson Pierce dons the persona of Black Lightning, he puts on a big afro wig and adopts a street-wise idiom full of black slang. This is intended to obfuscate his civilian identity as an upstanding member of society who talks “good English” and helps kids in the community by being a good teacher and a role model. What an excellent way to use the (secret) identity tropes of the superhero genre to explore DuBoisian double-consciousness! What a great opportunity to explore the construction of so-called authentic Black identity and its association with urban criminality and poverty!

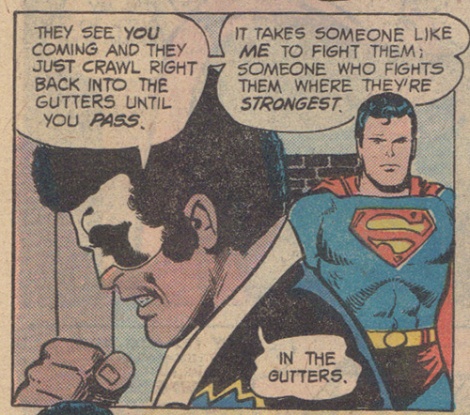

Isabella set up the aspects needed to do this—the crime is connected to people outside of the community preying on them and or manipulating their needs, the accepted and most visible authorities of the superhero community (like Superman) ignore them, from the outset Black Lightning has a contentious relationship with the cops, and so on. But these are mainstream comics, they were not ready to fearlessly explore this in the 1970s and they are not ready to do it now. I think that level of sophistication requires a more developed reading audience and the problem with superhero comics is that for the most part they still don’t know what audience they are aimed towards. As Adilifu Nama writes in his great book Super Black (2011), “[Black Lightning] articulated an acceptable (albeit formulaic) version of Black Power politics as black social responsibility” (25), but who is the audience for that kind of representation of black power politics in comics even if the implicit white power themes of the genre desperately need that kind of balance? And is it all that useful a thing to try to explore when it is written as awkwardly as it is here? Look at the panel below, from Black Lightning #5. The superhero rhetoric about crime is just the kind of dehumanizing attitude about urban problems that does marginalized black communities no good.

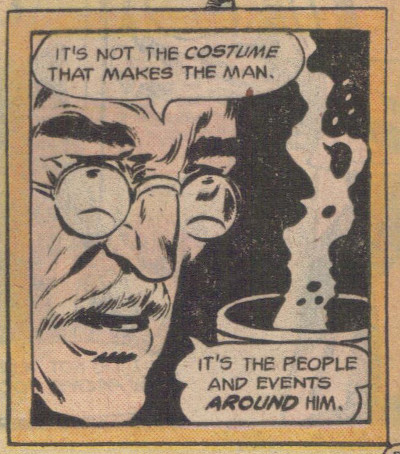

Before moving on, it bears mentioning Black Lightning’s co-creator, Trevor Von Eeden. As one of the few African-Americans working in mainstream comics at the time, he deserves more attention, not only because at such a young age he co-created such a seminal and potentially amazing character despite working in an industry hostile to people of color, but because he is clearly a talented comics artist, and while the panels I included from his work don’t show it, his run on the original Black Lightning always demonstrated an impressive fluidity of movement and had great expressiveness in his figures. He would go on to develop into an even better artist, as he was still a teen in the late 70s, and had room to grow. Furthermore, according to him, he was the one that convinced the powers that be how terrible the original idea for DC’s first African-American superhero with his own title, “The Black Bomber,” really was (and it was terrible – you can read about it here). Furthermore, there is an on-going dispute where Tony Isabella tries to take full credit for the creation of Black Lightning, when it was Von Eedon who at the very least designed his look (note how in the link above describing the “The Black Bomber” and the origins of Black Lightning Isabella doesn’t even mention Von Eeden at all!). Why should the writer get primary credit in a medium where words and pictures work together? It seems to me from what I have read that Von Eeden should have been allowed to have more influence on the character, especially since what Isabella ended up writing started weak and got worse when he got another chance in the 90s. As Von Eeden said, “If I wrote a Black Lightning story, it’d OPEN in a classroom–we’d get to meet Jeff Pierce’s students, and hear how they think, and what they have to SAY! I’m tired of black ‘heroes’ preaching to kids–whose p.o.v. they don’t even know.” Sounds like Von Eeden’s input could have led to something worth cherishing on its own merits, rather than on what could have been.

All that aside, what interests me most about the Black Lightning/Jefferson Pierce is something Von Eeden was not happy with: the awkward performance of blackness that the title tackles via the afro-wig and language shift. I am not sure that most white writers would be up to the task, but I’d love for a black comic writer/artist team to explore the idea of a successful African-American man abandoning his bourgeoisie pretensions to serve his community as an educator, and that also takes on a “down in the hood” persona to protect that community from the perniciousness of white supremacist capitalist forces that play upon the community both legally and illegally—while struggling with the problems of such self-conscious code-switching. I’d like something that seriously deals with the limited opportunities in those communities as they’d play out in the genre. This comic book could be brilliant. I imagine something like the DC comics version of The Wire, where even the best of cops and superheroes are corrupt or corruptible, where the system’s obsession with the appearance of success undermines an ability to try anything that might actually improve the communities most affected by crime. I imagine something where Jefferson Pierce has to come to grips with his own problematic position as a figure being held up as a role model for success in the black community, when being an Olympic athlete or even an a college graduate should not have to be the only way to escape the indignities suffered by so many of his neighbors and their kin. I imagine something where Black Lightning challenges the superhero status quo—where he’d decry that as the true super-villain. In the 80s, he’d be part of Batman’s The Outsiders (which were something like DC’s version of the X-Men), but I have no idea how explicitly the issues that would make his character the most compelling were ever explored in that title.

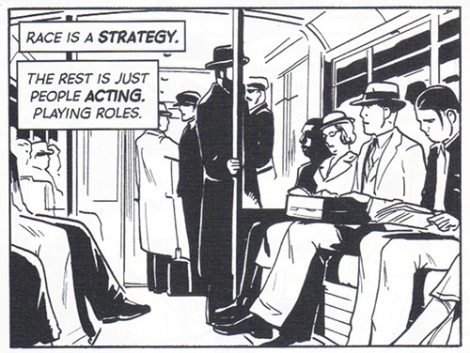

The idea of Jefferson Pierce “passing for blacker” is appealing because it provides a way to put the double-consciousness of the secret identity trope to bear upon the racial politics of the superhero genre, and to comment on our own racial politics. Black Lightning’s very conscious manipulations of both people’s expectations of him would make for a superpower I think a lot of people have in real life and put to use all the time. Most often we are just code-switching. It doesn’t make you a fake, it just makes you multi-dimensional and able to more deeply penetrate the many different facets of a community, which only appears homogeneous from a privileged position on the outside.

Reading Black Lighting made me think of Mat Johnson and Warren Pleece’s graphic novel Incognegro (2006). The similarity might not be apparent, except for the surface theme of being about black characters, but the approach to passing in both struck me. Typically, racial passing is characterized in terms of individuals taking advantage of the ambiguity of race to gain certain privileges—ranging from marrying into a white family (like Clare in Nella Larsen’s 1929 novella Passing) to just getting a table at the Waldorf-Astoria—but both these books are in conversation around the use of race and racial passing as a strategy for infiltrating a community to work toward changing it.

Mat Johnson writes Incognegro to be very self-conscious about race and identity, which makes sense given the fact that it deals with how African-American journalist Zane Pinchback uses his ability to pass for white as a way to infiltrate and report on southern lynchings in the 1930s—lynchings that were for the most part ignored by the dominant white media of the time. In other words, he is participating in some dangerous shit. Pinchback claims that it is white America’s lack of a double-consciousness around race that allows him to adopt the role of a white man. It is not only his light-skin, but also his astute observation of white southern culture, that allows him to blend long enough to gather information about lynchings and those involved. Similarly, Pierce’s adopting of a so-called “blacker” urban mode in donning the guise of Black Lighting is based on a double-consciousness. Understanding that his typical grooming and use of language is used to mark him as different from conceptions of “most blacks” in both white and black communities, his conscious change is meant to both protect his civilian identity and to better blend into the street life he is patrolling, garnering trust and gaining information about criminal activity. He’s like a one-man superhero Mod Squad.

Of course, Incognegro isn’t a superhero comic, but the opening discussion of identity certainly does echo that genre. His friend Carl calls him “Zane, the high-yellow super negro” and Zane, preparing for another trip south narrates, “I don’t wear a mask like Zorro or a cape like the Shadow, but I don a disguise nonetheless.” Unlike a superhero, Pinchback can’t save anyone. He can only observe and report. But perhaps part of my reason that I think of these two comics together is that somewhere between them is a comic I would not only want to read, but follow, buy and support (not that I wouldn’t support Johnson doing more comic work, nor do I mean that comics should be limited to superheroes). The thing about Incognegro is that the seriousness of the topic and the peril of the environment into which the protagonist and his northern friend, Carl (also passing) enter, makes the latter’s attitude about passing hard to swallow. He is just so painfully willing to play at being white and to ignore the dangers to himself and his friend (and unwilling to accept his friend’s wisdom as both a African-American that grew up in the south and who has also passed many times to infiltrate the sites of lynchings) that I have a hard time buying him as a character. Certainly even if Carl had lived his whole life in Harlem and thought of white southerns as dumb yokels, he should have known to fear of those lynch mobs, had some inclination to think back to those “A man was lynched yesterday” signs that were hung from the midtown offices of the NAACP. His comedic attitude towards passing and his wild exaggeration of whiteness (adopting an English accent) may offer some exploration about the socially constructed nature of race and stereotypes, but it does not fit the tone of the rest of the graphic novel—and certainly his final fate is anything but funny. I am not suggesting that it is played for laughs, but rather that Carl’s antics are laughable to the point of undermining my suspension of disbelief.

But maybe the superhero genre with its larger than life themes might be a better space in which to explore the comedic and the tragic (an tragi-comic) elements of race, racial passing and its many contexts. Perhaps there is a way for its “four-color” world to take advantage of the fantastic in a way that Pleece’s black and white art flattens the phylogenic racial differences we are so quick to see in the real world in order to make Incognegro work visually.

Incognegro does have other things going for it. The subplot of the sheriff’s deputy being a woman living like a man develops a compelling connection between the social construction of race and gender. The book also suggests a conflict between Pinchback’s anonymous work passing for white to report on lynchings and the opportunity for recognition as a writer provided by the Harlem Renaissance. Overall, it is a lot more sophisticated than Black Lightning even tries to be, but that isn’t a surprise given the literary writer and the subject matter.

The lynching theme of Incognegro also made me think of the poem or saying that is part of Black Lightning’s schtick, “Justice, like lightning, should ever appear to some men hope, to other men fear.” There is an unspoken double-consciousness at work there as well, because “justice” is not a neutral term or idea. Lynch mobs thought they were dispensing justice. The men that killed Emmett Till thought they were dispensing justice. What kind of justice was ever won for the countless black men (and women) who were lynched in the south (and north) to this day? I am not sure about that “ever should” part of the quote, but it certainly does appear as hope and fear to the very people that Black Lightning and Zane Pinchback are trying to help. The proclivity of “stop and frisk” is evidence that this kind of thing continues today. People like Mayor Bloomberg considered it a form of justice, but who defines justice?

The 1995 version of the Black Lightning title is in many ways worse than the 1977-78 version. I have not read Black Lightning’s time with Batman’s team The Outsiders, so I am not sure what he was written like then or what his relationship to black communities was in the 80s, though one of the letters included in issue #3 of that second volume gives me a clue—“I was never a fan of Black Lightning in the past; his anger and arrogance rubbed me the wrong way, But now that Tony Isabella has toned the character down some I find him much more likeable.” The letter writer’s attitude makes me think that Black Lightning is just the kind of black superhero character I want—not kowtowing to the white establishment of the superhero community. Can you imagine resenting the confidence and anger of a college-educated Olympic athlete superhero who is trying to help out his historically marginalized and terrorized community?

It seems what that letter writer probably really liked about the 90s version of the comic is how black urban America is represented as being every bit as terrible as the imaginations of white people could develop in the crack wars era. Many of the letters speak to how “real” it seems and make comparisons to Detroit and Chicago. It is incredibly violent. The colors are ever dark and muddy. It is full of stereotypical characters and very hokey use of African-American slang. I have only looked at the first story arc (issues #1 through #5), but unlike the original series there is no sense that the community that Black Lightning is trying to help is anything but a violent and hopeless place with a black political machine that exploits it. Sure, these ideas are not bad in and of themselves, but as others have explained many times—when the field of representations of African-Americans is so narrow, the few ways we get to see them in comics is troubling. Basically, the 1990s Black Lightning title was an attempt to cash in on the popularity of the wave of movies like Boys in the Hood, New Jack City, Juice and the like (just as films like Shaft and Super Fly influenced the creation of Luke Cage). The “realness” of the comic representation is being measured against representations of those communities in entertainment narratives (and I am including representations in the news as an “entertainment narrative”).

In the end, I want to like Black Lighting, and when I consider the character as I imagine he could be—as he is in that one panel from Infinite Crisis—it is easy to think of him as being my favorite DC character. All I need to is ignore the limited and problematic exposure he has had and imagine him representing something bigger, not taking shit from the likes of Superman or Batman, or you know just “the Man,” and inscribe him into my own narrative of the potential for the superhero genre. All I need do as reader is to think of his as not only struggling against super-villains or Tobias Whale, but against his own representation in the genre.