The index to the Indie Comics vs. Context roundtable is here.

____________

As an avowed post-modernist, I have been known to proclaim that “context is everything” on more than one occasion. And because context is everything, one of my favorite things in the world is when a creator takes a property and recontextualizes part of it. Done properly, this can provide an entirely different viewpoint on something that I thought I knew and understood.

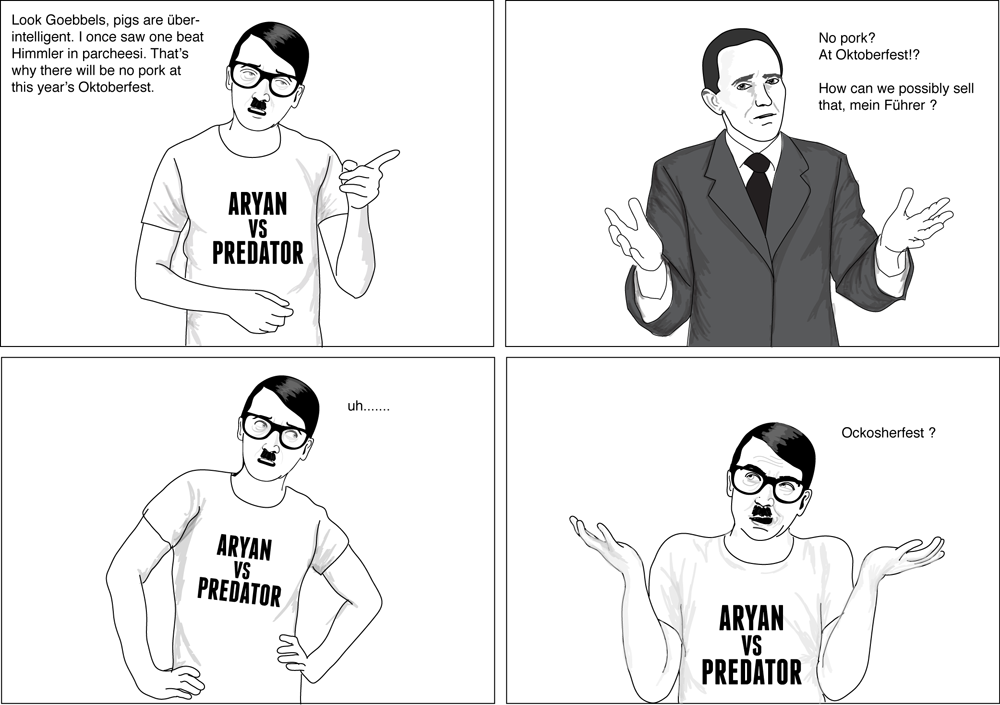

For example: Hipster Hitler by James Carr and Archana Kumar. The high concept is pretty straightforward; in his character bio, the authors write “Failed artist, vegetarian, animal rights activist, asshole – it all just fits.” The concept was originally presented as a webcomic and was subsequently published in book form by Feral House.

(And yes, Hitler was a real person, not a fictional character. However, it could be argued that he has become a larger-than-life caricature of a villain since his death. This is certainly the viewpoint that the comic is written from.)

In Hipster Hitler, the recontextualized Hitler is presented alongside his generals and advisors, who are still in their original context. As you would expect, the interaction between generals and a hipster who happens to be their leader provides the majority of the comic energy in the series. The only other recontextualized character in the series is Joseph Stalin, who is presented as Broseph Stalin, complete with red Solo cups and a popped collar.

What makes the series interesting to me is that a detailed familiarity with both contexts – World War 2 and contemporary hipsters – is required to really understand all of the humor. The best thing about the series are Hitler’s t-shirts, white with a pithy saying. One of the more obscure ones reads “Artschule Macht Frei.” To get the joke, you have to know that Hitler didn’t get into art school and that the phrase “Arbeit Macht Frei” (Work sets you free) was over the gates to Auschwitz – clever, but in poor taste. The joke in another strip turns on the knowledge that Hugo Boss designed the uniforms of the Wehrmacht.

Drawing the parallel between Hitler and hipsters didn’t take a lot of work, but writing an entire book of jokes about the juxtaposition without being too overtly offensive did. To a certain extent, anything that humanizes Hitler has the potential to be offensive just by its very nature. Here, though, the comparison doesn’t cast Hitler or hipsters in a favorable light. And that’s why I think it works.

Mind you, it doesn’t say anything profound about the human condition, World War 2, the Third Reich, Hitler or hipsters. But then again, it’s not trying to. As far as I’m concerned, the whole thing is just a vehicle for some really entertaining t-shirts – “Three Reichs and You’re Out,” “Under Prussia,” “Ardennes State,” “I Control the French Press.”

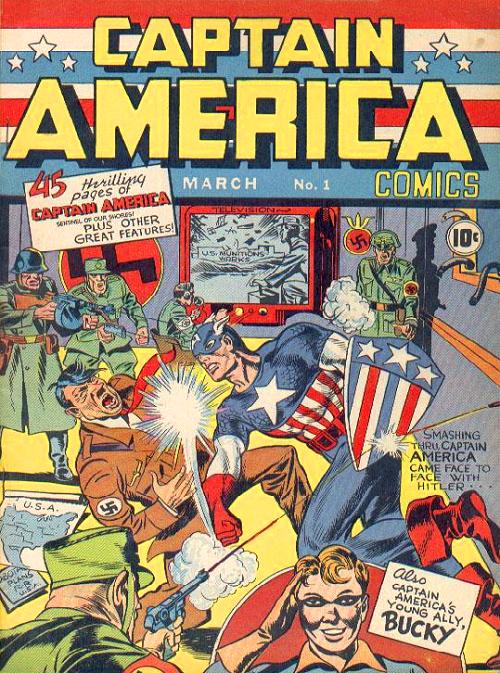

For more profound insights into the human condition I look to American Captain by Robyn. Presented entirely on a dedicated Tumblr, the premise of American Captain is that Captain America (from the movies) is dealing with the culture shock of waking up 40 years later by producing a series of autobiographical comics.

The two contexts are fairly obvious – the universe of the Marvel superhero movies and the world of autobiographical comics, which we get mostly through the art style. There’s a third, less obvious context, however – fandom. The entire point of the series comes directly from the fandom impulse to interrogate the inner lives of characters as revealed in settings and scenarios that are other than the canonical appearances. This comes through in the description of the premise, at the point where I had to specify which Captain America was being presented.

Understanding American Captain does not require nearly as much contextual information as Hipster Hitler does, but it helps if you’ve at least seen The Avengers. Still, a diary comic written by a fictional superhero is a concept that begs to be at least partially unpacked.

In addition to the understanding that Steve Rogers has an artistic background and would probably gravitate to autobiographical comics as a form of self expression (which has a weird mirror in the canonical comic series in the 1980s, when Mark Gruenwald had Steve Rogers penciling the Captain America comics), the series explores the fish-out-of-water experience of a time traveler from the past. In the comic book, this is old news and Steve Rogers has long since acclimated to the present. But in the movie universe, this is still relatively new information, ripe for exploration.

A few strips capture quiet one-on-one moments among the team and there is an entire series of strips following Pepper Potts, who has taken it upon herself to educate our narrator about recent art history. One of the more profound sequences follows Steve Rogers and his undiagnosed PTSD and the ways he deals with the revelation that he’s not as mentally together as he’d like to believe.

The strength of the strip is in the vulnerability that Rogers reveals in his diary comics. Presumably, nobody is reading them but him. However, we know that isn’t the case because we, the readers, are reading them. By doing so, we get a direct insight into his most personal thoughts and interactions in a format that is utterly private (or so the conceit goes).

The effect is unsettling and deliberately so. A man who wakes up decades after everyone he knows has died is not going to have an easy time adjusting to the modern world. The biggest issues will be the smallest things. In a universe that seems to be focused on blowing stuff up real good, being able to slow down and appreciate the details is a breath of fresh air.

Whereas Hipster Hitler is primarily concerned with from pointing out that certain entitled personality types have been around for much longer than we’d like to believe, American Captain is more subtle and nuanced. Considering that the former is a comedy and the latter is focused on the quiet desperation of Steve Rogers, this makes sense. However, both work because someone noticed that there is more than one way to look at the characters.

By picking the characters up from their original context and shaking off the detritus that has accumulated over time, the original foundation of what makes the characters who they are is revealed. Hitler is a hipster. Steve Rogers is an artist. Context is everything.