I was glad to see mention of writer Christopher Priest’s long run on Black Panther (62 issues, 1998-2003) in the comments on Qiana’s post about African American comics. Partly this is just because I have a real affection for those comics, which I consider to be among the smartest superhero serials of their day. It’s also partly because I think Priest’s run is very much engaged with some of the questions of what makes a comic an “African American comic” in ways that haven’t always been appreciated. This becomes especially apparent in the later issues of the series, none of which have been collected or reprinted. The intro that Qiana mentions is housed on Priest’s site along with a host of other writing about his time in the industry that I’d recommend to anyone interested in questions of race in comics – not just the narratives but the industry, too. When you take all those essays together, one quality that emerges is Priest’s ambivalence over his position in the comics field — or maybe over his legacy, since he’s no longer really active. As the first African-American editor at Marvel and DC and the first African-American solo writer, he’s a figure of historical importance in comics, and reasonably wants that to be recognized. Yet he’s also wary of being pigeonholed as a “black writer” and only being offered “black books”

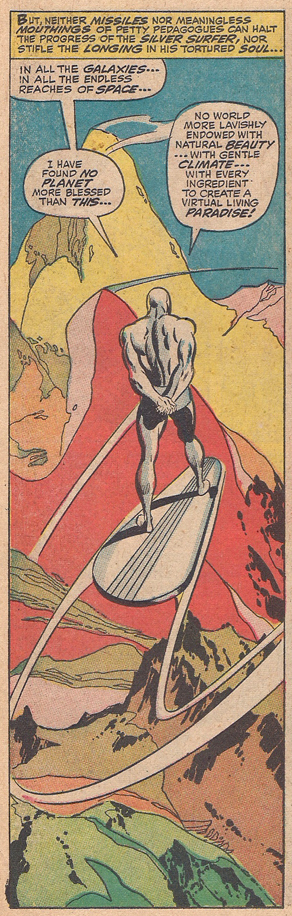

Just what makes a book a “black book” is the question, of course. The Black Panther is an interesting case in point here. He’s the first black superhero, and it makes sense to think of Black Panther comics as “black comics.” But he was created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, and much about the character — his costume, his name, his setting, his origin, his supporting cast, his powers, his conflicts — was created by white writers and artists up to the point that Priest took over. (Artist Billy Graham is the only exception I can think of, though there may be others.) Though Priest praises aspects of previous creators’ takes on the character, especially the original Lee/Kirby stories and the work of Don McGregor, he also indicates that, whatever the good intentions or noble efforts of those creators, no one had really been able to get the Panther over with comics’ predominantly white readership. The character had been relegated to eternal B-list status, because, Priest argues, to write him well would be to acknowledge that an Afrofuturist superhero-king with the resources at the Panther’s disposal would upend the basic conventions of superhero storytelling in the Marvel Universe. Is it possible to acknowledge these realities and have the book succeed with an audience that is pretty happy with those conventions, thank you very much? Is it possible to offer a new take on the Panther that explicitly contrasts with his traditional depiction without having fanboys cry foul? (If you think that’s not really a concern, just remember the online controversy that ensued when Dwayne McDuffie wrote a sequence in which the Black Panther puts the Silver Surfer in a headlock; see also here for a selection of now-deleted responses to McDuffie’s use of Storm and Black Panther in FF that included calling for a “lynch mob”).

These questions are at the heart of what I think is a very shrewd, thoughtful engagement with race and comics history in Black Panther. In the pages of his run, Priest explicitly contends with the character’s problematic history, frequently utilizing retcons to develop his depiction of T’Challa as a strategic mastermind and ultra long-range planner whom no one, including his ostensible pals on the Avengers, has ever really taken seriously enough to understand. The example many people remember from early in the series is the revelation that he only joined the Avengers in order to spy on them because he perceived the explosion of American superheroes as a potential threat to the sovereignty of his kingdom of Wakanda. That emphasis on the Panther as a monarch is key to Priest’s depiction. He gets labeled a superhero because that’s the only way Americans, who are blind to the cultural significance of his ceremonial garb, can make sense of him. His real peers, as the “Strum und Drang” storyline (#26-29) makes clear, are other monarchs such as Doctor Doom, Namor, and Magneto — men for whom morality is (at least) secondary to the protection of their kingdoms. If it bothers you that Panther is consorting with supervillains, well, that just goes to show that you’re still viewing him through the wrong lens.

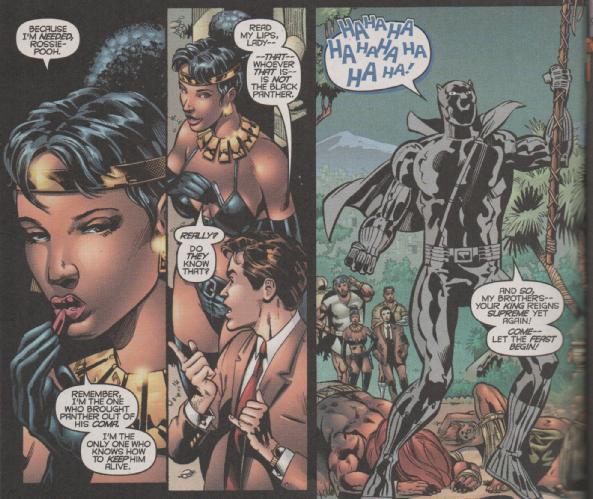

But in addition to rewriting the character’s history, Priest also struggles with the character’s future. He doesn’t own the Black Panther, after all. Even if he writes a “definitive” Black Panther story, his definition will only last until the next writer comes aboard with his or her own ideas and directions. Some of Priest’s most interesting work on the series comes in its third and fourth years, as Priest begins imagining potential futures for the character, potential ends to his story. For instance, in issues 36-37, Priest riffs on The Dark Knight Returns, using an “imaginary story” to examine how an older, slower Panther comes to terms with how his commitment to his kingdom has alienated him from his family and turned his son into a terrorist. But the questions of the Black Panther’s past and future come together most intriguingly beginning in issue 35, with the discovery of a duplicate Black Panther kept in stasis, hidden away in a desolate corner of Wakanda – a duplicate that T’Challa’s old foe Man-Ape describes as “the true, the original Black Panther!” When we next get a look at the character, this time in action (#40), it seems like Man-Ape might be right. The duplicate Panther is wearing his classic uniform from his debut in Fantastic Four #52, and he easily commands the respect of Wakanda’s warring tribal factions with his natural authority and high-minded rhetoric.

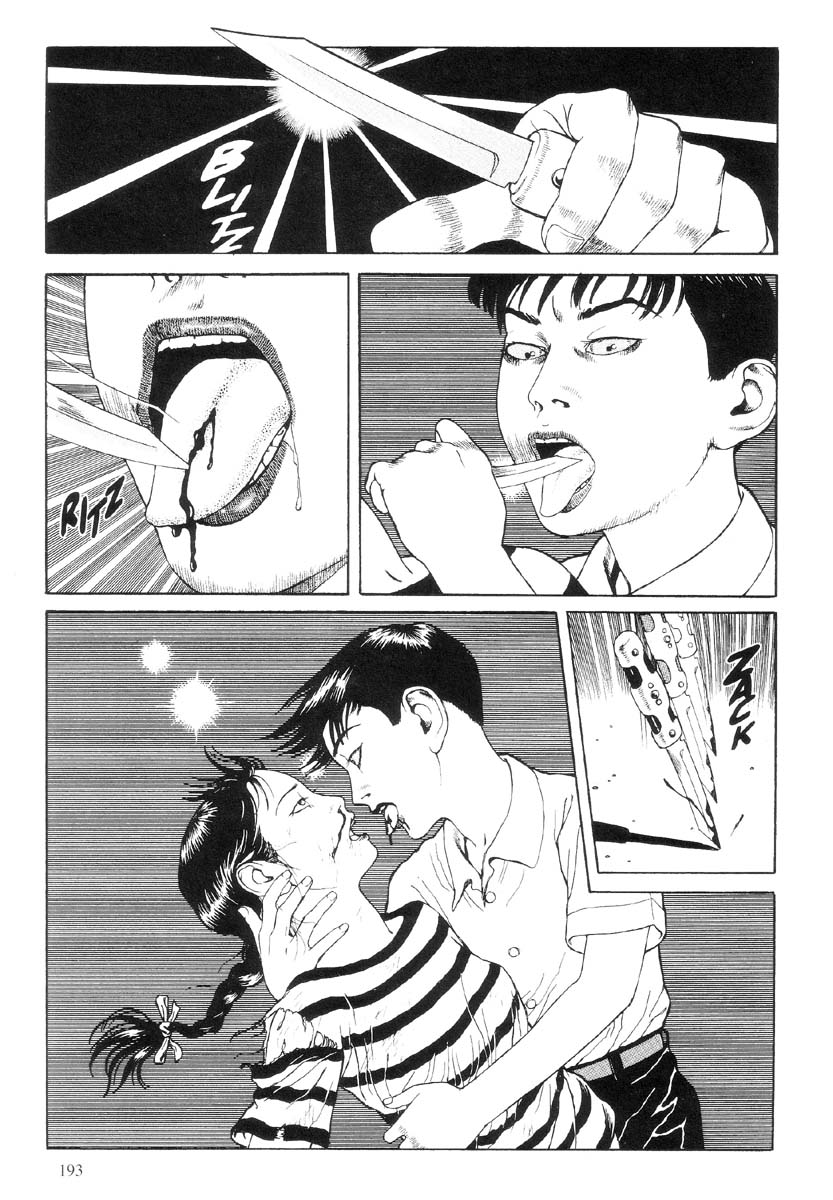

But take a closer look. Something is up here. The Panther isn’t just wearing his classic Kirby uniform –he’s also drawn in the Kirby style. The chunkier, blockier line and distinctive Mike Royer-esque inking make him a “visual alien” –to use the immensely useful term coined by Jones, one of the Jones Boys, here at HU— in a world defined by the smooth Neal Adams sheen of Sal Velluto and Bob Almond, who provided the art for most of the series’ run.

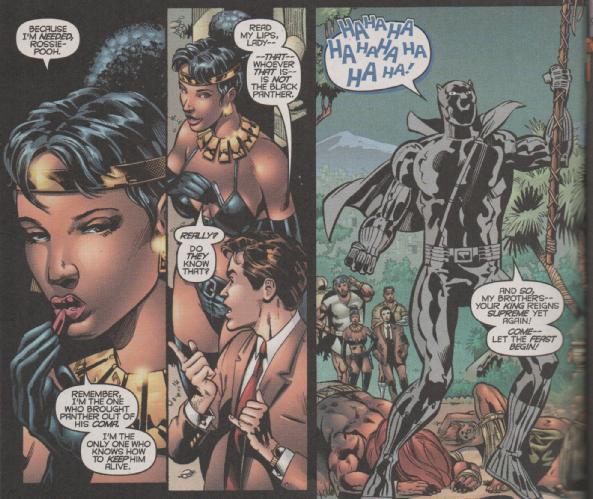

From Black Panther#41 by Christopher Priest, Sal Velluto, and Bob Almond.

With the appearance of Kirby Panther, the metatextual aspects of Priest’s narrative become explicit. The unsettling, awkward effect created by Kirby Panther’s distinct visual appearance, which he maintains throughout the run, reflects his role in the series. He represents a kind of interpretive crisis for the readers and for the book’s supporting cast: Is he the real Panther, preserved in amber since the last time King Kirby touched him, and the self-serious, arrogant Panther that we’ve been reading about is a fraud? Or is this a bit of revisionist comics metacommentary in which a simpler, happier version of a beloved character climbs out of the memory hole to chide his contemporary incarnation for his unheroic ways and unclean thoughts? Or is he there to demonstrate the ridiculousness of the original Black Panther, a well-meaning embarrassment that can be superseded now that someone who truly understands the character is finally in control of his destiny?

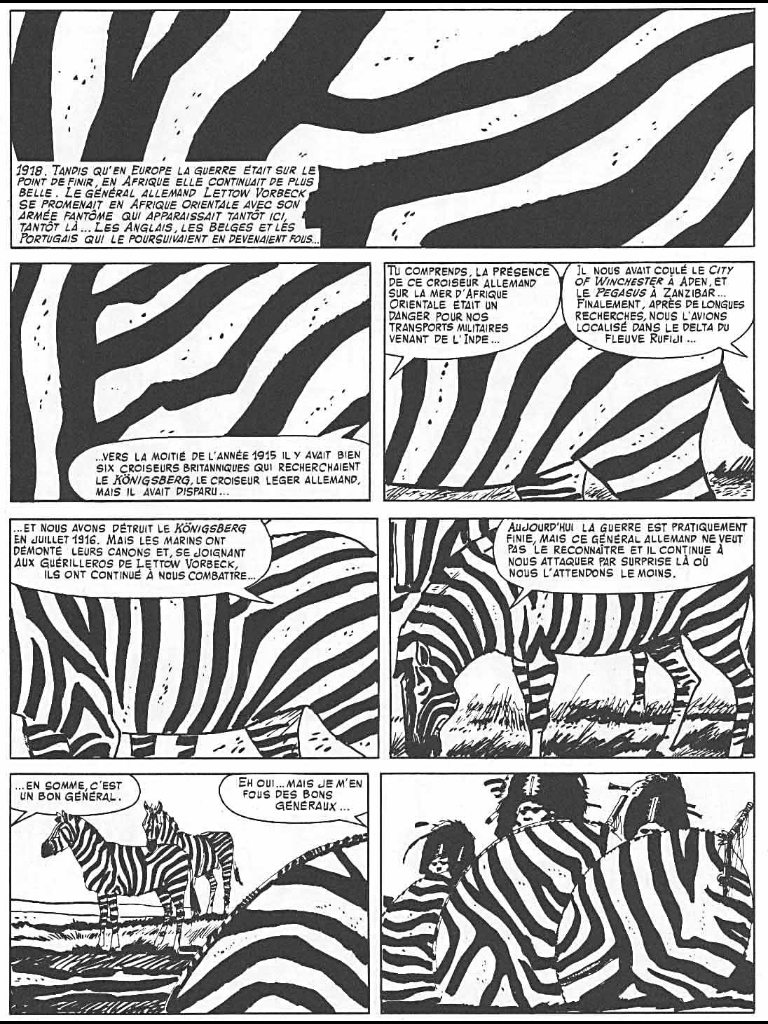

I should stress here that this Kirby Panther is a very particular Kirby Panther, having less in common with the Panther in his first Fantastic Four appearance and more with the voluble, buoyant hero of Jack Kirby’s 1977 Black Panther series. Kirby cast T’Challa as a giddy adventurer-king who quested after priceless treasures and triumphed over weird menaces with vigor and elan. Oh, and he had ESP. This makes it hard to give a simple answer to any of those questions above. I think those late-era Kirby Black Panther comics are enormous fun, but it’s easy to understand how an audience who had gotten used to the angsty meolodrama of Don McGregor’s Jungle Action would have seen them as a jarring shift and maybe even a step or three backward in sophistication. It’s arguably also the era of the character’s history in which race receded furthest into the background. One could make the case that, in contrast to McGregor’s Wakanda, a richly imagined nation of contending political forces with a complicated history, Kirby’s mythical Wakanda might as well be Asgard — although Adilifu Nama in Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes argues compellingly for the significance of the 1970s Black Panther as a kind of aspirational Afrofuturist space-opera hero. But in any case, what we have here, or seem to have here, is the reappearance of a “classic” version of the character (Kirby is his co-creator after all, can’t get more classic than that) who is also an off-model version, one about whom readers of Kirby’s series were strongly divided.

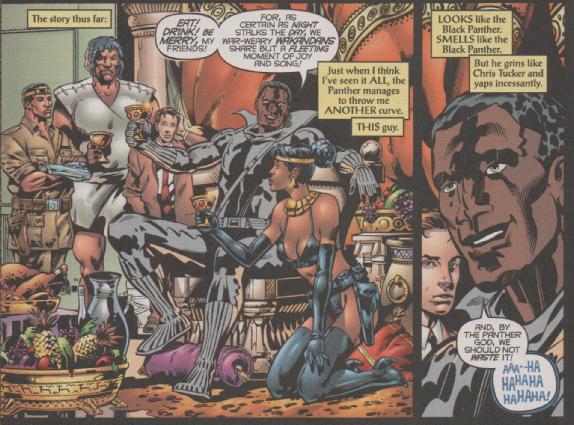

From Black Panther 49 by Christopher Priest, Sal Velluto, and Bob Almond.

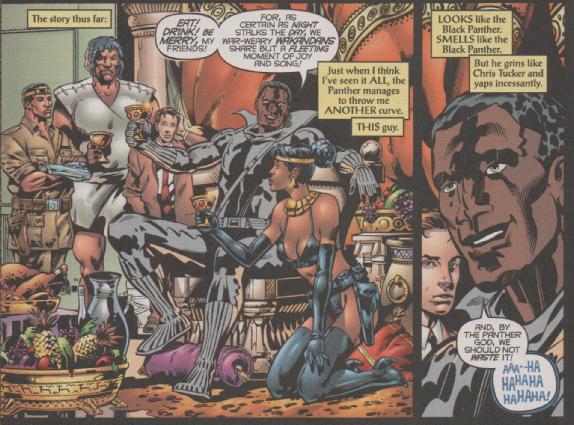

But again, Priest is up to something a little different. At first, Kirby Panther seems to function in ways that could let you make a case for any of the possible interpretations I mentioned above. Nearly everyone in the supporting cast treats him as faintly ludicrous — Ross refers to him as the “‘Look, I have Pupils!’ Fruity Pebbles version of the Black Panther” (#42) and “Ross Perot in a kitty suit” (#43). He laughs constantly. He quickly accumulates more and more elements of the Kirby series, breaking the quarantine that Priest Panther has imposed to get his old band of treasure-hunting frenemies — Abner Little and Princess Zanda, also drawn Kirby-style — back together. They embark on a madcap caper that contrasts with the grim business of the main story, in which Priest Panther wages a physical and political battle against Tony Stark, trading body blows and hostile takeovers in order to protect Wakanda’s sovereignty (and, as it turns out, that of the United States). When he’s with Priest Panther, Kirby Panther urges him to embrace life and live in the moment in a manner which could be read as charmingly old-fashioned or mildly insane: “I am the best part of you! I am that which you now wholly deny yourself! . . . Call in the Dancers!” (#41). (He calls in the dancers a lot.) Yet his exuberance proves so infectious that even Ross, the Priest Panther’s closest confidante, begins to think that his friend may be the imposter after all.

From Black Panther 41 by Christopher Priest, Sal Velluto, and Bob Almond.

But there are no imposters. And Kirby Panther is not a blast from the past. He’s displaced in time — but he’s from years into Priest Panther’s future. Through the powers of King Solmon’s Frogs, two golden frogs that can snatch warriors from anywhere on the timeline and an important plot device in Kirby’s run, Kirby Panther has mistakenly ended up back in his own past. Priest Panther was keeping him in stasis not from shame or to protect his throne, but to save his life. Both men suffer from a degenerative brain condition, the result of a battle with Iron Fist. Kirby Panther’s has progressed to the point that merely to stand is agony, despite his bravado. At some point down the line, it seems as though Priest Panther will inevitably accept his swift-approaching fate and adopt Kirby Panther’s carpe diem perspective. In some ways, though, this revelation only complicates the question of how Kirby Panther functions in the narrative — is he a cynical reminder that the character, owned by Marvel Comics, is essentially impervious to any of the changes that Priest might want to make, and he’ll ultimately revert back to a baseline characterization established by his creators?

I don’t think that’s how he functions, but I do think that’s the anxiety that Priest is contending with. There’s a key difference,however: Because Kirby Panther isn’t the original Kirby Panther, but instead a visitor from the future, he has already been Priest Panther. And the ruthlessness and strategic mastery, the downright meanness, of Priest Panther, is part of his history now. Priest makes this clear in issue 45. When Priest Panther is preparing to go toe-to-toe with Iron Man, Kirby Panther knocks him out and takes his place, and he proves to be every bit the methodical, unsentimental, ends-focused schemer that Priest Panther is. His finishing move is hacking Tony Stark’s artificial heart and sending him into cardiac arrest, an act that the story presents as a potentially unforgivable violation of the friendship between the two men – not the sort of thing you would have seen in Kirby’s series. The costume swap between the two Panthers continues on for a couple of issues, underlining that these are two aspects of the same character, not a real character and a fraud.

Kirby Panther dies in issue 48 and touches off a chain of events that lead to T’Challa abandoning the throne. The series, never a strong seller, got one more chance at life with a soft reboot under Priest’s guidance, having T’Challa train an upstart New York City policeman to be a superhero. (As the White Tiger, this character, Kasper Cole, became one of the stars of Priest’s short-lived follow-up series The Crew.) It’s not really clear if the idea is that Kirby Panther’s death frees Priest Panther to take a different path or that now he’s locked him into a time loop — time travel theorists can puzzle that out. But ultimately, I’d argue that Priest gets to have it both ways. Yes, his time with the character is finite, and ultimately he may always be more strongly associated with a “classic” take. But by creating a Kirby Panther who is marked by the experiences of Priest Panther, he metaphorically asserts the significance of his take on the character, insisting that it is going to be a part of the character’s history even if future writers emphasize other aspects, that it’s impossible to ever really wipe the slate clean and go back to earlier times. Or maybe he’s not asserting the significance of his take but just expressing a longing for that significance.

In some ways, this desire to ensure that one’s contribution is lasting and recognized is probably no different than the way anyone who has a healthy run on a corporate comics property feels. But I’d argue that it’s fundamentally connected to the questions that sparked this whole discussion and in particular to the question of what it means to produce “black comics” in the context of the American comics industry. Though it seems paradoxical, Priest’s solution to the dilemma of how to produce a comic that takes a nuanced and complex view of blackness in an industry dominated by conventions that would impede such a view being fully realized, for an audience that has a narrow, often negative view of what a “black comic” is, starring a character who bears the weight of forty years of history, is to enter into a kind of metatextual collaboration with the works of prior artists and writers, however skillful or hamfisted they may have been, and to find ways to simultaneously honor and rewrite their contributions. (In some ways Priest’s approach to writing Black Panther fits well with the model of misprision and revision that Geoff Klock suggests is the defining component of contemporary superhero narratives in How to Read Superhero Comics and Why.) Priest’s use of Kirby Panther is maybe the most obvious example, but I think the whole series can be fruitfully read as a meditation on difficulty and complexity involved in creating a “black comic” within the constraints of the American comics industry.

______

Just as a side note, I only sporadically followed this series when it relaunched under writer Reggie Hudlin, but I’d be curious to hear how those who followed Hudlin’s Black Panther thought he negotiated these questions, especially since Marvel seemed to make a concerted effort to make his series a more integral part of its shared superhero universe.