A little bit back I wrote a piece about the upcoming black Captain America and the idea of Black superheroes more generally. In the essay I said:

So, on the one hand, a black Captain America is a strong, and welcome, statement that the American dream isn’t just for white people — that black folks can, and for that matter, have been heroes. On the other hand, though, a black superhero who just does the superhero thing of fighting criminals or anti-American spies or traditional bad guys can seem like a capitulation. Fighting against crime in the U.S. means, way too often, putting black men behind bars. Will a black Captain America serve as a kind of “post-racial” justification for that law-and-order logic? Or will he, instead, open up a space to question whether law, order, and superheroics are always, and for everyone, a good?

Criminals in the United States are insistently conceived of as black. Superheroes are iconically crime fighters. A black superhero is forced to confront that contradiction one way or the other — since even ignoring it becomes a kind of confrontation.

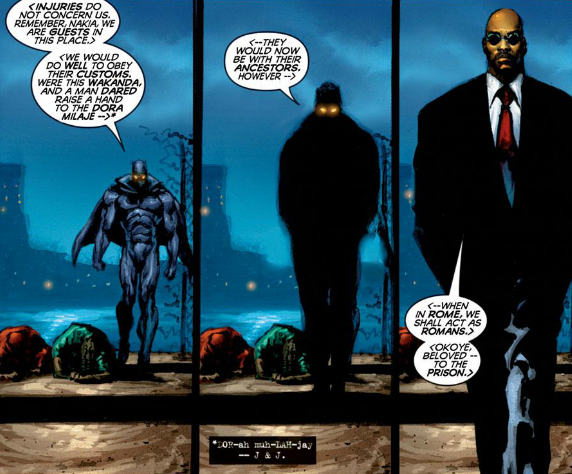

I just read the first volume of Christopher Priest’s Black Panther(art by Mark Texeira and Vince Evans), which is definitely aware of this issue, and works to address it. In the series, Black Panther is a superhero who isn’t really a superhero; he’s the king of Wakanda, a fantastically advanced African nation. He may pose as a crimefighter for his own reasons, but really he has only an at best peripheral interest in putting bad guys behind bars, or in fighting for truth, justice and the American way. You could say he’s passing as a superhero. He’s pretending to assimilate and to be one of those oh-so-folksy Kents, but in fact he’s still true to his advanced, alien Krypton — still an other, who does not belong in America, and who doesn’t have any particular desire to belong.

This is a clever, and powerful, critique of the superhero assimilation narrative, not least because of the metaphorical resonance. Black people, after all, are the one immigrant group that is never allowed to assimilate, and the one group that has most reason to know why assimilation with the as-it-turns-out-not-all-that -virtuous-Kents is not necessarily all that it’s cracked up to be.

At the same time, though, the comic is, at least in early issues, never quite willing to push the criticism all the way to its logical conclusion. Priest talks openly in his intro about the fact that the series is trying for compromise. This is most obvious in the narration by Everett K. Ross, a white guy who Priest says “interprets the Marvel Universe through his Everyman’s Eyes,” and who is “a new voice, seemingly hostile towards the Marevel Universe (and by extension, its fans.” That’s one way to read it…but you could also see Ross as a sop to those same fans, giving them an identifiable white point of insertion to interpret Panther’s amazing, mysterious blackness.

Priest’s negotiation with the superhero genre goes well beyond the use of Ross, though. The whole plot of the volume is designed to make Panther act like a regular old superhero, complete with tracking down criminals, interrogating suspects, and beating up (mostly black) gangsters. Wakanda finances a charity for inner city kids in New York City; the publicity poster child is mysteriously killed, and so Panther decides personally to abandon a volatile political situation in Wakanda in order to track down the girl’s murderer. He intends to return to Wakanda as soon as possible…but in his absence, there is a coup, and to avoid further bloodshed he is forced to remain in the U.S. and keep on superheroing. Tough break for the Panther, good luck for the superhero audience.

There is some ambivalence about Panther’s superheroing in the comic. His foster mother and others back in Wakanda tell him he’s being foolish for abandoning his kingship to be a cop (though his mom doesn’t put it quite that way.) And later it turns out his mother and the guy who usurps the throne were actually in cahoots to trick Panther to come to the New York. Rather than fighting the bad guys as a superhero, the bad guys essentially trick him into being a superhero. Supeheroing is a trap; to the extent that Black Panther is a superhero, he’s a rube.

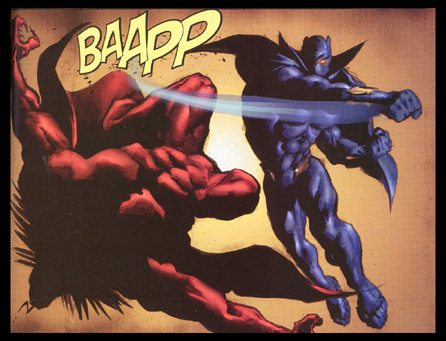

Just because the comic knows that superheroing is a trap, though, doesn’t change the fact that superheroing is a trap. Black Panther is presented as an awesomely powerful, superintelligent, spiritually advanced African king who knocks out the devil with one punch but still can’t get out of a story where his main function is to hit monsters.

“Why the hell are you wasting your time with this crap, you idiot?” is a barely subdued subconscious chorus that echoes jarringly against the more overt insistence that “Black Panther is awesome!” Making a black man a superhero, Priest suggests, can’t help but show the limits of superheroing; there’s a slapstick futility to gods and kings with vast powers slugging “bad guys,” rather than attending to the more consequential kingdoms and injustices that start to be hard to miss when the world isn’t quite so insularly white. You wonder, perhaps, if Priest is prodding, or questioning, his own genre investments — if he too, like his main character, feels a little hemmed in by the narrative in which he’s found himself; a story he clearly loves, but which just as clearly wasn’t made with him, or his (helplessly super) hero in mind.