So John Simms is now Michelle Gomez. Presumably Time Lords have always had the regenerative ability to change sex, but it took a half century of Doctor Who adventures before anyone dared to notice. The villain’s new body also gives the former Master the ability to stick her tongue into Peter Capaldi’s mouth. The Guardian’s Mathilda Gregory wasn’t shocked: “Discovering the Master had kissed the Doctor and called him her boyfriend didn’t seem odd, because there has always been sexual tension between the two, but seeing Missy being able to express it made it clear how heteronormative TV can be.” Matt Hill at ScienceFiction.com was more irked: “If this is the way the Master felt like treating the Doctor, why is it the only time we see a kiss [is] when the two participants for all intents and purposes fit a heterosexual norm?”

I agree, but I’m intrigued by a larger pattern of villainy. Why do evil homicidal men keep turning into evil homicidal women?

I’ve been catching up on old episodes of Syfy’s Haven with my wife and son, and 2012’s season three features a serial killer dubbed the Bolt Gun Killer (a possible homage to and/or knock-off of the cattle gun-wielding Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men). He not only murders women, but he slices off his favorite parts to stitch into a new body. The Killer is clearly male—the blurry surveillance image proved it even before detective Tommy Bowen is unmasked—but that Frankenstein body he’s making isn’t his bride. It’s himself. Like Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs, he’s sewing a new skin so he can become a woman. Except the Haven writers (I seriously doubt Stephen King had any influence on this plot arc) gender flip the gender flip by revealing that the skinwalking killer was originally a woman who now slides in and out of birthday suits, male or female, while busy assembling one that looks like her old self.

She wants to impress her returning husband (he spent a few decades in a magic barn and/or alternate dimension), and her plan more-or-less works. But no one comments about the Bolt Gun Killer’s gender and sexuality ambiguity. When “she” slips on a man is “she” still a woman? Or is she a man with a female gender identity? Since the Killer’s spousal devotion is constant, does that mean she changes sexual preference when she changes genitalia? In the Troubled universe of Haven, are gay men and straight women the same under the skin?

Chris Carter belly-flopped into similarly murky waters in the 2008 The X-Files: I Want to Believe. A pair of gay villains, Janke and Franz, abduct women to extract and sell their organs on the black market. Except sometimes Franz needs a whole body for himself—everything but the head (which Janke buries in a field for the FBI to find with the help of a psychic pedophile priest who molested Janke and Franz as altar boys). Franz’s first and presumably male body may be in that ditch too, though it’s unclear how long his team of assistants has been removing his head and reattaching it to new bodies. Women’s bodies. Are women just easier for Janke to abduct? Or does Franz have a female gender identity? And if so, how does Janke, a gay man, feel about his husband’s new vagina? In the outed truth of Carter’s Catholic universe, are gay men just straight women attached to male heads?

Again, Carter and his co-writer, like the Haven writers, don’t comment on the implications—they don’t even seem aware that their fantastical sex change operations sew up anything but plot holes. There are other examples—the female H. G. Wells from another Syfy show, Warehouse 13; Tim Curry’s Dr. Frank N. Furter, that “sweet transvestite from Transsexual, Transylvania” landing on Earth via The Rocky Horror Picture Show—but I prefer the original transsexual supervillain/ess because s/he is also the original comic book supervillain.

When Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Ultra-Humanite debuted in Action Comics No. 13, he was a bald guy in a lab coat and wheelchair. All those seemingly unrelated adventures during Superman’s first year—a crooked football coach, a war-profiteering munitions manufacturer, a circus-foreclosing loan shark—were all part of the retconned Ultra’s improbable plot for world domination. Superman thwarts him four more times in 1939, ending with the villain’s explosive death in No. 19. He’d mysteriously vanished from plane wreckage in No. 13, but this time Shuster draws the corpse. “Dead!” declares Superman.

Action Comics No. 20 introduces Dolores Winters, a Hollywood actress who lavishes Clark with thanks then cold shoulders him the next day. “It doesn’t make sense!” he exclaims. “Females are a puzzle—movies queens in particular!” After the “vixen” kidnaps a yacht of millionaires and threatens to murder them, Shuster draws the first wordless panel in Superman history.

“Those evil blazing eyes,” declares Superman, “there’s only one person on this earth who could possess them . . .! ULTRA!”

The “person” confirms: “My assistants, finding my body, revived me via adrenalin. However, it was clear that my recovery could be only temporary. And so, following my instructions, they kidnapped Dolores Winters yesterday and placed my mighty brain in her young vital body!”

Although Shuster draws that young vital body with his standard vixen proportions, Superman can’t drop the male pronouns. “He must have as many lives as a cat!” he says after Ultra’s inevitable escape, wondering “will he continue his evil career?” But when Ultra returns in the next issue, the captioned narration accepts her sex change, mentioning “her last encounter” and “her hideaway.” Even Superman adjusts, calling her a “madwoman.”

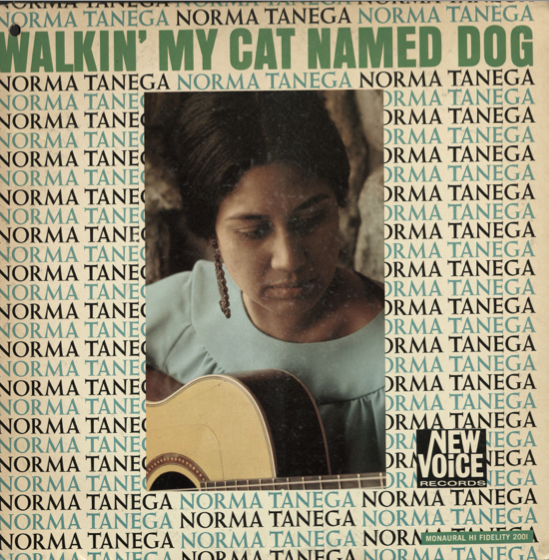

Ultra expressed no sexual desires before his operation—so 1939 readers, like 2014 Doctor Who viewers, would have assumed he was straight. But given all the young vital bodies available for transplantation, why did he instruct his minions to stick his brain inside a gorgeous woman’s skull? Next thing he’s using his new pussy (a cat trapped in a fence) to seduce a male scientist—but that’s just to get the scientist’s atomic-disintegrator, right?

Ultra pulls on a pair of pants before leaping into a giant vagina–I mean, volcano–at the end of No. 21, but the next issue begins the two-parter that introduces Lex Luthor to the Superman universe. Ultra never returns. “It all seems to be a terrible nightmare!” declares the pussy-freeing scientist. Superman doesn’t want to talk about it: “Well, leave it go at that.”

I’m thinking Siegel’s cisgendered editors wanted to leave it go too and told him to flip villains. 1939 wasn’t ready for transsexuality. 2014 may be past it.

Ultra, Franz, and the Bolt Gun Killer have one thing in common: a brain. The rest of their body parts are detachable, but their skull-housed sexualities and gender identities seem constant. Franz is a straight male brain. Bolt Gun and Ultra are straight female brains. None of them actually change. The Master is different. I’m not sure exactly what happens inside a Time Lord’s cranium during regeneration, but the brain–the physical organ–must transform with the rest of the body. Only the mind remains. Which means a Time Lord’s identity transcends anatomy: the Master is neither female nor male, neither gay nor straight. Time Lords have no baseline sex or sexuality. The Doctor Who thought experiment posits a universe in which cisgendered-heteronormality isn’t even a possibility.

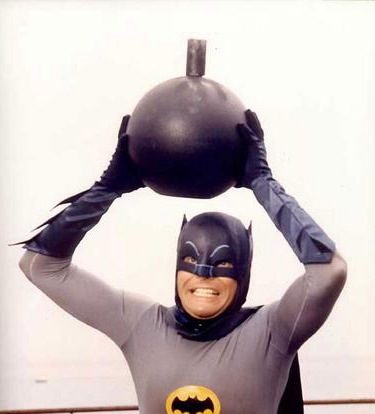

The Master is also the first sex-changing villain whose sex change isn’t a manifestation of his villainy. Franz, Ultra, and Bolt Gun are variations on Buffalo Bill–a character so two-dimensionally vile, audiences root for Hannibal Lecter instead. Bill is subhuman, and his homicidal attempts to become a woman are his only defining feature. Except possibly his thigh-tucked penis:

The Mistress stands apart from Bill, Franz, Ultra and Bolt because she didn’t abduct and murder actress Michelle Gomez to get her body. Missy is still a homicidal psychopath, but her sex change isn’t monstrous. The character may be evil, but not the transsexual transformation. That’s a first in pop culture supervillainy.