In case you didn’t know, in February of 2013, at the end of 700 issues of Marvel’s Amazing Spider-Man, Peter Parker died. Well, Otto Octavius aka Doctor Octopus, as he lay dying in a prison hospital, managed to switch bodies with his greatest nemesis, and then his body died with Parker’s consciousness or spirit or whatever still in it. Essentially, Dr. Octopus became Peter Parker, aka the Amazing Spider-Man, now referring to himself as—with no sense of irony—the Superior Spider-Man. The Amazing Spider-Man title that started in 1963 ended with that 700th issue and Marvel began a new series, The Superior Spider-Man, also written by Dan Slott (with pencils and inks by varying artists).

This was a controversial move among die-hard Spider-Man fans, especially those active in various internet forums and on Twitter. They were not happy with Dan Slott (though not as unhappy as many were at the prospect of a black Spider-Man, but that’s not really surprising). There have been plenty of things over the years that have made Spider-Man comics fans unhappy with the Marvel writers and/or editorial. The most prominent among these was the “soft reboot” of Spider-Man’s continuity in 2008 that magically dissolved Peter Parker’s 1987 marriage to Mary Jane Watson and put his secret identity back in the bag after the events of 2006’s Civil War (to name two events that many fans also complained about when they happened), but to actually kill Spider-Man and have someone else take his place unbeknownst to everyone else in the Marvel Universe? That is akin to saying that the Peter Parker we’ve known for years was really a clone of the real Peter Parker who’d actually been wandering America with a faulty memory since the 1970s! Oh wait…they did that once already. It didn’t stick.

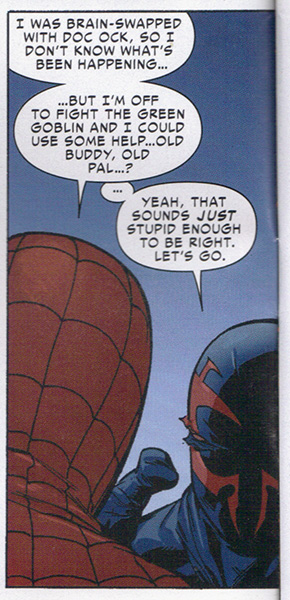

Of course, this didn’t stick either, and comics fans should have known better. In the penultimate issue of Superior Spider-Man, Peter Parker’s consciousness regains control of his body, and he saves the day. Soon after volume 3 of Amazing Spider-Man began with what I assume will be a long story about putting to right everything Octavius did wrong. I don’t know, I have basically dropped the Spider-Man titles for now…perhaps in the future there will be another iteration I’ll be interested in. But here’s the thing, a returned “real” Peter Parker/Spider-Man will still be responsible for whatever ills caused by Doc Ock assuming his identity, just as he is still responsible for everything done by previous versions of Peter Parker/Spider-Man who made poor choices because of the thread of shared identity, regardless of what changes to the character have been made, undone or forgotten.

If there is one thing we can count on in mainstream superhero comics it is the strange tension between the accretion of change and the status quo. That is, while the status quo tends to draw characters back towards it, undoing the events of intervening issues, the changes back and forth and the inconsistencies they engender become part of that on-going story. Even when writers and editors don’t explicitly bring them up within the narrative as they are happening, chances are some creative team down the line is going to pick out that rupture as a way to develop a rehabilitative narrative and turn the story back in on itself. Honestly, I never know if I should love or hate this kind of thing in serialized superhero comics. It seems awfully insular, but at the same time some really fun stories and creative thinking through attention to detail have come out that way. I guess, the most accurate answer is that sometimes I love it and sometimes I hate it, depending on how well it is written. I love the mid-80s revelation that Mary Jane knew Peter Parker was Spider-Man all along, and the related account of her abusive and poverty-stricken family that belied her party girl attitude. But I hated the early 2000s recasting of Gwen Stacy’s time in Europe before her death as a time when she secretly gave birth to Norman Osborne’s rapidly maturing Green Goblin offspring.

Superior Spider-Man is the latest iteration of this cycle. It is just that by appearing to remove Peter Parker altogether, ending a 50 year-long series and starting a new title, the change seems all the more extreme and hostile to fans that abhor change and uncritically embrace their facile notions of tradition. However, Dan Slott seems to have been attempting to accomplish something interesting with the character of Peter Parker/Spider-Man with this series. By temporarily removing him, Slott provides a narrative space for a rehabilitation of a Spider-Man character that despite his self-righteous pretensions regarding power and responsibility has a long history of both abusing power and being something of an impulsive jerk. Furthermore, the inconsistency of how characters are written over the decades means that there are extreme cases where Peter Parker/Spider-Man has been particularly self-centered, immoral or brutal. For example, there’s the 90s story where Peter struck his then pregnant wife Mary Jane (Spectacular Spider-Man #226). Or the 60s comic where he refused the Human Torch’s help with the Sinister Six (Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1), despite his aunt and girlfriend being in danger. Or, in the 80s, when he brutally beat up Doc Ock and tore his mechanical limbs from his body in Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man #75.

Even Slott has contributed to this when he had Spider-Man condone and participate in Guantanamo-style torture of Sandman for information during the “Ends of the Earth” story-arc. Peter didn’t even bother with the usual moral-wrestling afterwards.

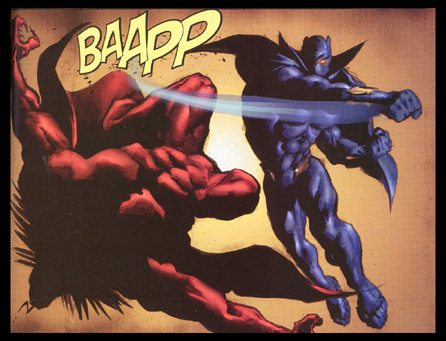

Slott attempts a potential rehabilitation of Spider-Man not by trying to put the genie back in the bottle and writing a Spider-Man that annoyingly clings to a classic and pollyanna notion of his morality, but by going in the other direction. He gives us a Spider-Man who adopts the dubious code of the contemporary superhero, who does the things that so many fans want their “heroes” to do and gives us the piling consequences to such an approach. In other words, the Superior Spider-Man blurs the line between the behaviors of heroes and villains in the superhero genre by muddying the very identity of the hero within the narrative itself, rather than by creating a new character (like Spawn) or a parody of an existing character that exists in a separate narrative space (like Lobo was supposed to be to Wolverine). In the course of 30 issues, the Superior Spider-Man kills two different super-villains (shooting one in the head!), viciously beats three others (two of whom are harmless, jokey type foes), blackmails J. Jonah Jameson (currently acting mayor of the city of New York) in order to get a property for his own secret headquarters (Spider-Island), hires groups of armed minions, sets up his own network of surveillance cameras and spider-bots all over the city, and never considers the rapey implications of being with women under an assumed identity.

He charges head first into the criminal status quo, using the language of “finally doing” what other superheroes, like Spider-Man, never have the guts to do. He destroys “Shadowland,” Kingpin’s ninja-filled headquarters and reveals the current incarnation of the Hobgoblin’s secret identity the first chance he gets. Basically, he acts decisively, aggressively and without a thought to the consequences. He is always sure that what he is doing is right, and if not unambiguously and morally right, then at the very least justified. When Mary Jane Watson’s nightclub catches fire, rather than swing over there to save her no matter what, like Peter Parker would do, Octo-Parker merely alerts the fire and rescue authorities and chooses to take out Tombstone and his toughs instead. Mary Jane is surprised when her confidence in her hero’s arrival ends up being misplaced. Octo-Parker doesn’t care about her feelings, he only cares that he did the rational thing. Most versions of Parker would have agonized over the choice.

I am of the school of thought that what makes the Amazing Spider-Man work as a comic book is not Spider-Man himself, (or at least not just Spider-Man), but Peter Parker—both in terms of his relationship to his alter-ego and his various social relations with his large supporting cast. The Superior Spider-Man for the most part eschews his social obligations for his own ambition. Sure he is able to maintain a better relationship with his Aunt May (a point made creepy by Otto’s romance with May once upon a time) and a romance with fellow scientist Anna Marie Marconi (my favorite new character from the series), but only because he is also willing to ignore what he deems as “petty crime,” unconcerned with the potential personal costs of those crimes as the real Peter Parker learned to be upon the death of his uncle.

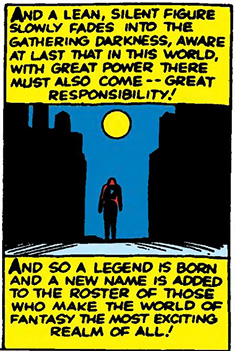

It seems to me that Superior Spider-Man is a kind of answer to a particular kind of fanboy complaint about Peter Parker’s frequent whining and self-doubt. At its heart, Spider-Man comics have been best when they successfully mix a kind of high-flying urban adventure story with characters deeply enmeshed in a setting rife with contingencies. In other words, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility” is not about doing “the right thing,” it is really about there being no right thing. There are no good choices. There is only taking responsibility for the outcome of your choices. If anything, Peter Parker as sad sack who occasionally snaps at the people around him and takes on the guise of a happy-go-lucky nut in a bright blue and red costume making with the snappy patter as a form of catharsis (and cathexis), shows us an attitude to the world that is more real (and subsequently paralyzing) than our own often is. The various tales of Spider-Man highlight the complex (forgive me) web of human interaction. It is like a four-color version of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men. The more you can do the worse the possible outcomes for doing it.

To put it as succinctly as I can, the story of Spider-Man’s origin begins with his sense of responsibility for his inaction—not doing something, not stopping that thief led to the death of his Uncle Ben. Thus he decides to make his life one of action. As the 60s cartoon theme-song says, “wealth and fame he’s ignored / action is his reward.” However, moving beyond that origin point, taken broadly, the Spider-Man narrative seems to be actually about the equal dangers of taking action. Everything Spider-Man chooses to do has consequences, some foreseeable and others not so much, and all of them, even when he succeeds, are to some degree bad. This is especially true when he acts impulsively, like in Amazing Spider-Man #70, when he decides to stand up for himself and put a scare in J. Jonah Jameson, but then realizes he may have given the man a heart attack!

It becomes clear, looking over the arc of Amazing Spider-Man with the 31-issue run of Superior Spider-Man as a kind of coda, that “With great power, comes great responsibility” is not referring to the responsibility to do good that comes with great power—it is everyone’s responsibility to try to do good—but that the consequences of acting have a greater reach the greater your power. Even one of Spider-Man’s most classic scenes reinforces this idea—when saving his girlfriend from a plummet off the George Washington Bridge, the snap of her head when caught by his web breaks her neck and kills her. The tragedy is compounded for the reader by Spidey’s self-congratulatory monologue upon catching her and as he pulls her back up. It may not be Spider-Man’s fault that Gwen dies, but it falls in the realm of his responsibility. In the epilogue story aptly named “Actions Have Consequences,” in the final issue of Superior Spider-Man (this one written by Christos Gage), Mary Jane and Carlie Cooper (another of Parker’s exes) even discuss Gwen’s death in the context of Peter’s responsibility and their own safety. As Mary Jane succinctly puts it when Carlie confirms that Peter was taken over by Doc Ock: “Explains a lot. Doesn’t change anything.”

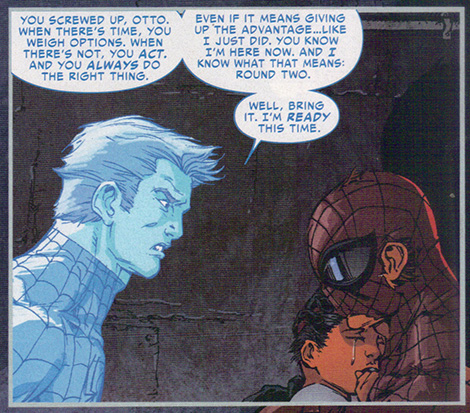

Unfortunately, like most things superhero comics, because of that tension between constant change and adherence to an always returning status quo, whatever promise Slott’s Superior Spider-Man run may have had to explore this idea of responsibility as a core aspect of the Spider-Man character collapses by series end. Unable to deal with the multiple moral quandaries set up by the Green Goblin, Octavius makes the noble sacrifice. He erases his own memory and consciousness from Peter Parker’s body, allowing Parker’s psyche to take over again. In that moment the story becomes not about responsibility, but about some essential Peter Parker-ness that makes him best suited for the job. Boring. In fact, it is worse than boring: the manifestation of Parker’s spirit or psyche or whatever (don’t ask me how it is supposed to work) makes a defining statement that actually makes his perspective indistinguishable from Octo-Parker’s. He says, “When there’s time, you weigh the options. When there’s not, you act. And you always do the right thing.” But isn’t that basically what the Superior Spider-Man has been doing for the 30 issues before this confrontation, because he was sure that his every choice was right?

It certainly doesn’t help that the moment of the “real” Parker’s triumphant return is marred by Giuseppe Camuncoli’s lackluster art and his seeming inability to draw a recognizable Peter Parker. He has a tendency to draw faces like characters are in the middle of an aneurism after straining too hard on the toilet.

Ultimately, what interests me about Superior Spider-Man is its existence as a self-contained example of the flexibility of identity made possible by serialized narratives. There is an incredible torsion of serialized comic book characters, a slow (and sometimes fast) twisting of a character’s identity until editorial has no choice but to declare that the character was a Skrull or a space phantom all along. Much like he did with his run on She-Hulk (though more subtly), Dan Slott plays with this meta-knowledge, by having Spider-Man’s Avenger cohort check him for those possibilities. But the possibility they can never check for without mimicking She-Hulk’s addressing of the fourth wall, or being written into the self-reflexive comic world that Alan Moore created when he took on Supreme, is that this strange-acting version of Spider-Man is the result of 50 years of changeless change.

Or perhaps, it might be more accurate to adopt Paul Gilroy’s notion of “the changing same” to the discussion of serialized comic book identity. Rather than look for an authentic identity as emerging from a relation to some originary moment or particular period of time (like the Silver Age or the Ditko era), we should see it as a developing diverse set of possibilities bound together at any given point by a shared set of collected signifiers that have come together to represent the character. As such, at any period of time the same set of signifiers may not all be present, or have made room for newer ones or to rehabilitate ones previously abandoned.

While the crisis in Superior Spider-Man revolves around the changes evident to those close to Peter Parker/Spider-Man, to the public at large, Spider-Man has not really changed. He is an unpredictable enigma upon which preconceived notions can be projected. Sure, some of Parker/Spidey’s relatives, peers and other companions can tell something is off about him, but the Spider-Man identity remains mostly unchanged in that whatever bizarre behavior he may be exhibiting must be seen in context of a figure that once leapt around the city in an iron spider suit, or a black costume, or a black costume with a slavering maw, or with two extra sets of arms, or drove around in a Spider-Mobile, or…or…or… In other words, he remains a colorful figure that is always changing—compelling but potentially dangerous.

I have not read every Spider-Man comic ever published, but I’ve read enough to appreciate that Slott’s Superior Spider-Man distilled a particular essence of the character that at least feels like a thread that existed throughout the character’s history. There are other elements of the character that have been emphasized over the years—his “spiderness” in Stracyzki’s strained and mostly ignored “The Other” storyline, his employment at the Daily Bugle, his relationships with women, his totemic rogue’s gallery, his run-ins and misunderstandings with the law. But his struggle over the range and depth of his responsibility to others has basically always been there. In removing it as an obstacle to being Spider-Man, Slott manages to put it back in focus as essential to making 50 years of continuity cohere.

[This piece has been cross-posted on The Middle Spaces]