Kanye’s mocked for taking himself so seriously. Kim is seen as frivolous to a fault. The truth, of course, is each is always both: he is really playful, and she has incredible drive. In deed and word, they are powerful—if not perfect—forces for racial, gender, and LGBT equality. You’ll note that only one half of the couple receives any real recognition for it. It’s not a coincidence that he’s the one with the frowny face.

“Kanye should lighten up” and “I can’t take Kim seriously” sound like different critiques, but they’re both centered on the idea that one must attend to every matter in life with the appropriate degree of gravitas. It’s a value judgment that’s so instinctual and self-evident that it’s easy to mistake for a matter of fact. When our values don’t align with someone else’s, an easy way to diminish or discredit their perspective is to suggest they should be talking about something else. Something more worthy of consideration.

You’d think the world of comics would be sensitive to this brand of condescension since it still has a chip on its shoulder about being Serious Adult Art. But many of the same people who have built their lives around the idea that comics are Very Important see no irony in telling people to lighten up about issues surrounding racism or sexism. Consider this piece on representation in Avengers toys, which was described by one prominent comics critic as an “aggressive article about culture war,” and as “fannish overidentification” by another. Those guys aren’t going to say the author of the article is wrong—heavens no!—but they sure do think it’s odd that anyone would care so hard about something as soulless as corporate merchandise. Around the same time I saw another comics blogger who dedicated three paragraphs of a Very Special Post to her observation that people should talk less about Sansa Stark and more about Boko Haram. Fortunately, she’s doing her part to engage with the problem of rape by directing readers’ donations to…a random Paypal that funds computers for orphans. LOL?

The notion that lowly fandom distracts us from meaningful political engagement is not new, but it seems to me it’s been gaining traction lately, particularly among nerds. Simon Pegg recently criticized science fiction as an opiate of the masses, going so far as to invoke the patron saint of People Who Need You to Know How Hard They Give a Fuck, Jean Baudrillard. “There was probably more discussion on Twitter about the The Force Awakens and the Batman vs Superman trailers than there was about the Nepalese earthquake or the British general election,” Pegg writes. (Cluck cluck!) His point about the monetization of nostalgia wasn’t wrong, but that post was maybe half as smart and humble as he thought it was.

“Talk more about earthquakes, sheeple.” –Baudrillard

Meanwhile Freddie deBoer’s out there pushing his critique of media types who indulge in what he calls “performative love of black culture”—e.g., praise for Beyoncé and The Wire—in lieu of meaningful, challenging political discussions. Beyoncé thinkpieces aren’t going to build a better world is more or less his point, and you could object to it for any number of good reasons. For me, it resonates, though I don’t quite agree. Sure, there’s any number of more pressing matters one could choose to talk about. And yes, there is a certain sameness across publications that makes for an unhealthy critical landscape. I too perceive a flatness in tone…the vague detachment of clever people talking about clever things…the sound of content shedding its skin.

Recently deBoer put forward yet another iteration of his Beyoncé argument, a critique of The Toast that garnered him pushback (especially from women), strong praise (largely from white men), and untold fame and fortune (also, presumably, from white dudes). It was based on “Books That Literally All White Men Own: The Definitive List,” a post written by one of The Toast’s founders, Nicole Cliffe. DeBoer used it to illustrate his longstanding complaint with white media types who are progressive, but not quite political, arguing that her piece is “indicative of a growing exhaustion, with desultory, rote online writing”—much of which functions to make white people feel less white under the guise of promoting equality. He describes the thought process behind that piece and its ilk: “‘Hey, you guys like lists. And you love calling other white people white. Here you go. Eat your slop. Enjoy.’”

Heaven knows there’s plenty of slop out there! But it’s worth noting that deBoer wasn’t the only white guy who had a serious problem with this particular slop; plenty of other dudes hated it too, and his reaction can’t be divorced from that context. Like those other guys, deBoer mistook the post as a failed indictment of white male liberal arts students. But his more serious mistake, to my mind, was writing thousands of words about Nicole Cliffe’s feminism in a post that totally failed to mention Nicole Cliffe or feminism. “We’re speeding for a brutal backlash and inevitable political destruction, if not in 2016 then 2018 or 2020,” he wrote, holding up one unnamed woman’s joke as an instrument of the impending apocalypse. “If you want to help avoid that, I suggest you invest less effort in trying to be the most clever person on the internet and more on being the hardest working person in real life. And stop mistaking yourself for the movement.” (my emphasis)

This last bit is an especially curious directive, couched as it is in a post that, for all intents and purposes, conflates Nicole Cliffe with Mallory Ortberg, a joke post with political discourse, and the agenda of a for-profit website with that of the progressive movement, whatever that even is. It’s this third mistake that gets my goat. The Toast is a vital feminist force, not because its content is political, but because it was founded on the radical notion that two women can publish whatever they want—whether it’s about Harry Potter fan fic, fitness, Ayn Rand, or motherhood—and people will read it. They were so successful in that venture that they launched a vertical where Roxane Gay publishes whatever she wants. This vision—an empire of sister sites in a media landscape where networks like the Awl and Gawker dedicate a single site among many to lady stuff—is even more radical than the one on which The Toast itself was founded.

Ronbledore wants YOU to join his feminist army.

The Toast has a strong identity amongst its increasingly indistinguishable brethren, which is not an accident. It’s because the site doesn’t approach feminism as a generic movement. It explores it at the micro level by talking about our public personas and our most secret self-images, our successes and failures, our political stands and our throwaway jokes. It cedes the floor to one voice at a time—an important methodology in a world in which feminism as a movement has historically failed (and is still failing) to accept and celebrate different ways of being a woman. These voices aren’t necessarily as loud as Lindy West’s or Caity Weaver’s or Natasha Vargas-Cooper’s, or as weird as Edith Zimmerman’s or Mallory Ortberg’s. They rarely, if ever, offer takes. Instead, they amble in and out of conversations about identity in a world where there’s a tendency to whittle women down to their best or worst qualities, ignoring any part that’s not convenient or a means to an end. In this context, promoting a spectrum of voices—and making money doing it—is a remarkable political act. Mistaking that for solipsism or putting on a show is a fundamental failure to understand the stakes.

In describing the appeal of Broad City, Amy Poehler once said, “The rule is: specific voices are funny, and chemistry can’t be faked.” This is advice worth considering with regard to the urgent work of building a coalition on the left. In my experience (in life and in politics), watered-down beliefs aren’t attractive. Nor is informing people that their interests are insignificant in service of propping up your own. The way to promote engagement and build community is not to ask people to assimilate in the name of the greater good; it is to meet them where they live. To be successful, you have to have the confidence and the conviction to meet them there honestly, as yourself. Incidentally, that’s precisely what Nicole and Mallory have done. Their audience is comprised of people who support the project I just described, not undiscerning fans who “will call anything [they do] a work of genius no matter what,” as deBoer wrote.

For a long time I wondered why deBoer seems to class everything written by media types as political discourse. The answer, it occurs to me, is simple: because that’s what he does. I think that’s cool; sometimes I even think it’s admirable. But promoting progressive unity shouldn’t be about remaking other people in your own image. If there’s any truth to the idea that the left is eating itself, I’m far less suspicious of callout culture and lazy writing than the Serious Men who demand that everyone engage with the issues on their own narrow terms. Meaningful change requires diversity in both background and approach. It requires room to let people pursue their particular preoccupations.

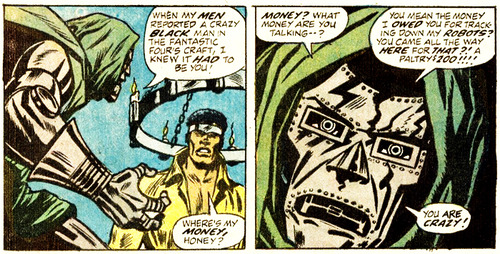

Meanwhile, the notion that we supplant real political engagement with blog slop and mindless entertainment is bunk. There’s not a writer in the history of the Internet who thinks his Beyoncé thinkpiece is going to change the world, nor is there a single nerd who thinks that Sansa Stark is more important than real people. Have a little faith that you’re not the last person on earth with a sense of proportion. Moreover, recognize the power of pop culture to propel political discourse. You can complain all day long about white people’s relationship to The Wire (which, by the way, has officially replaced liking The Wire as white people’s favorite way to distance themselves from whiteness), but the fact that its hero was a black gay vigilante has had a real, if not measurable, impact on the ways in which Americans think about race, justice and masculinity. David Palmer helped get President Obama into office. Almost a decade after his last appearance on 24, the American public still trusts him so much that he’s the face of Allstate Insurance. How crazy is that? If anything we’re desensitized to how crazy that is.

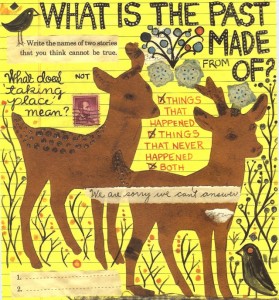

A deep abiding truth I’ve come to understand through the work of Lynda Barry is that identity is not just who we are or what we have. It is also who we can imagine ourselves to be. Stories are not an escape from our real lives; they are part of them. The imaginary past—the stories we read, the dreams we dreamed, the options we considered, and the stuff we dismissed out of hand—runs parallel to every action that’s fully realized. It constitutes an authentic contribution to our lived experience, impacting how we see the world and everyone’s place in it. It also affects how we envision the future—an act of imagination that is central to the liberal agenda.

from What It Is by Lynda Barry

One of the reasons I love the Internet so much is because it’s the natural habitat of writers who convey a strong sense of what their own two eyes see. It also showcases my favorite thing about criticism: how our smartest thoughts can be about stuff that seems stupid or inconsequential. Anything is inherently worthy of conversation. The old dichotomies of high/low, content/ads, IRL/online and art/merchandise are increasingly meaningless, for better and worse. If you want to analyze Internet culture with an eye towards improving it—a project that overlaps with how to promote solidarity on the left in curious ways, as deBoer suggests—you can’t just gaze upon its treasure. You also need to root through its trash. Forget Hazlitt essays and impeccably researched longreads. I’m talking Buzzfeed quizzes and the archives of TMZ. Anything. Everything. All of it. I’ve learned profound truths about this life from reading Gabe Delahaye on bad movies, Samantha Irby on irritable bowel syndrome, Jacob Clifton on Gossip Girl, Michael K on celebrity culture, CNN dot com, troll comments on Youtube, and Rusty’s most odious tabs. One of the wonders of our strange human brains is their capacity to find meaning in viral videos and silly vampire novels. It’s a sad and small-minded mistake to treat that as anything other than an opportunity.

__________

Follow Kim O’Connor on twitter: @shallowbrigade.