This post is one of my Twisted Mass of Heterotopia columns, supported by my Patreon subscribers. If you think it’s the sort of thing you’d like me to write more of, consider contributing (and thank you!)

________

Robocop 2 was mostly, and not wrongly, ignored when it came out in 1990, but it did manage to spark a smidgen of controversy. One of its major villains was Hob, played by Gabriel Damon, who would have been 13 during filming and looked like he could easily have been a year or two younger. Hob curses foully, dispenses narcotics, attempts murder, and watched vicious bloodletting while barely blinking an eye. Then he dies in a sentimental, tearful scene clutching Robocops hand.

Critics were appalled. “The use of that killer child is beneath contempt,” Roger Ebert declared. David Nusair added, “That the film asks us to swallow a moment late in the story that features Robo taking pity on an injured Hob is heavy-handed and ridiculous (we should probably be thankful the screenwriters didn’t have Robocop say something like, “look at what these vile drugs have done to this innocent boy”).”

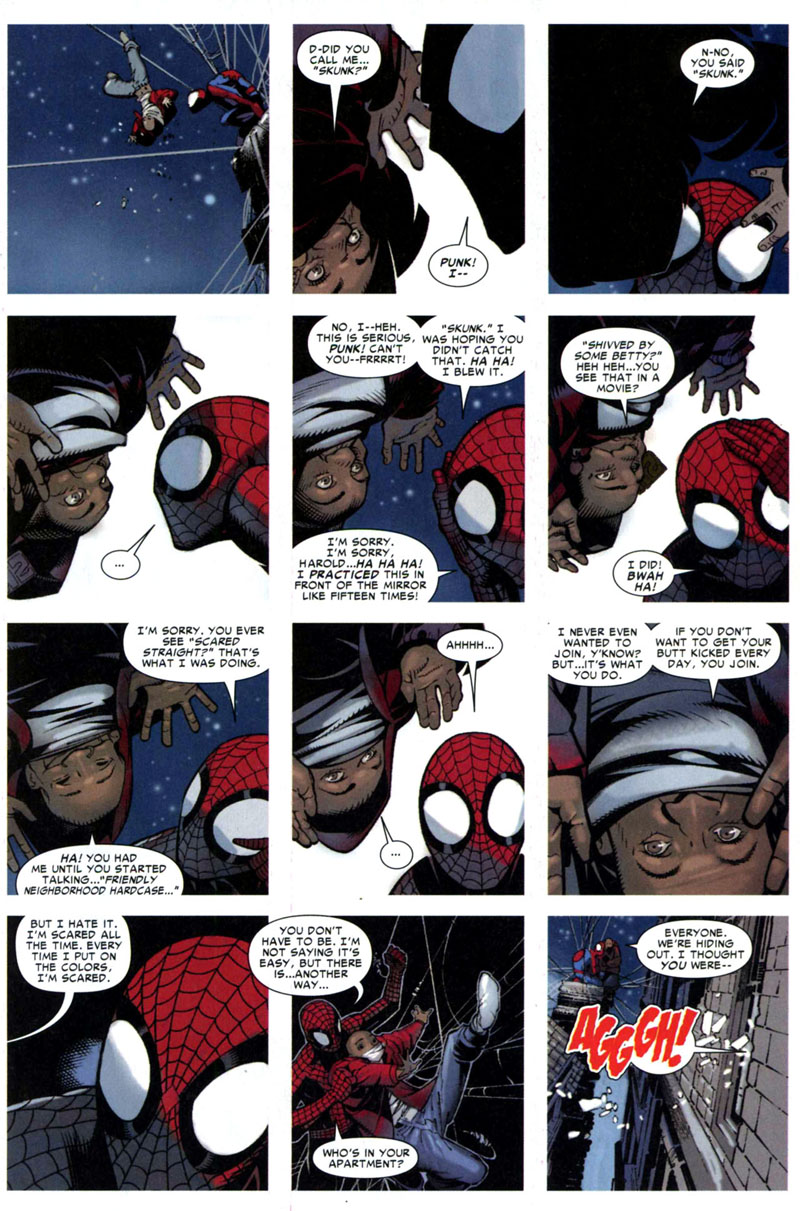

Ebert and Nusair aren’t exactly wrong. Robocop 2’s use of Hob is both gratuitous and cynical. Hob doesn’t need to be a child; everything he does could just as easily been given to an adult actor. There’s no effort to explain what a 13 year old is doing in the drug business, either. As far as the script is concerned, Hob is played by a 13 year old purely because it’s shocking to have him played by a 13 year old. It’s pure exploitation of a minor. Who can blame the critics for recoiling?

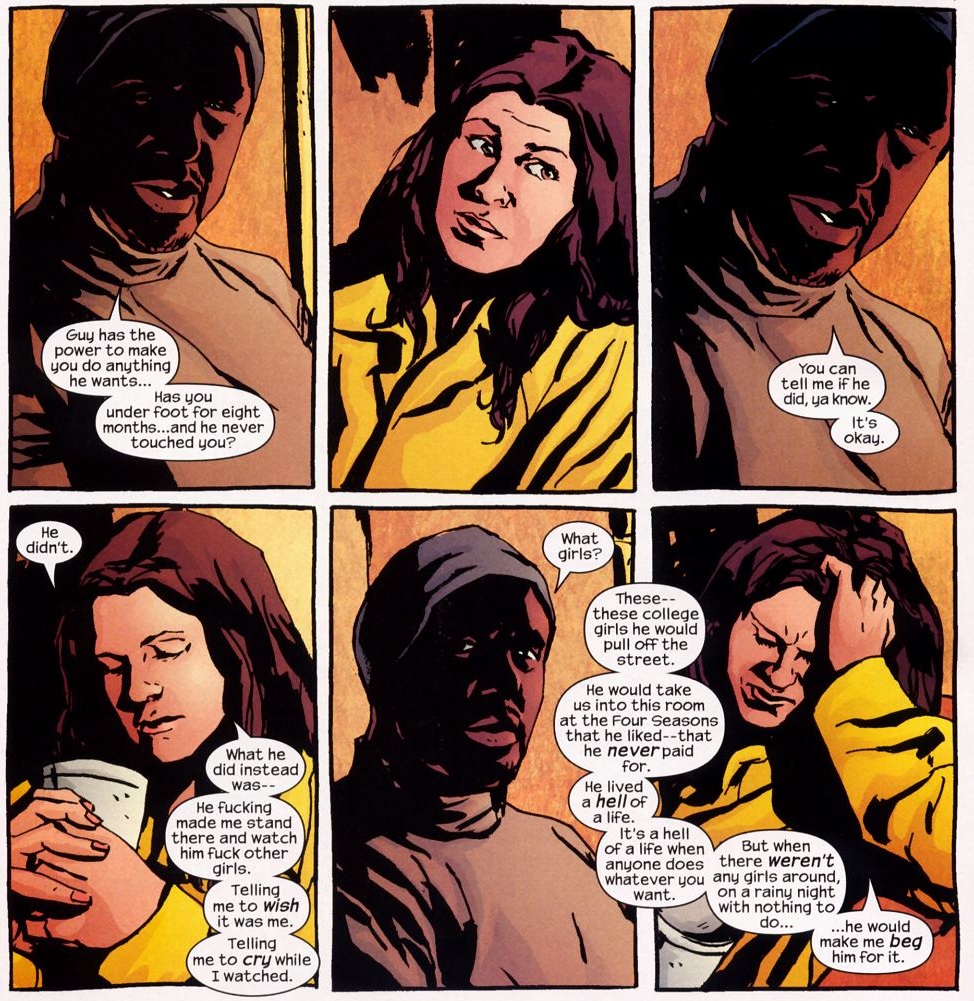

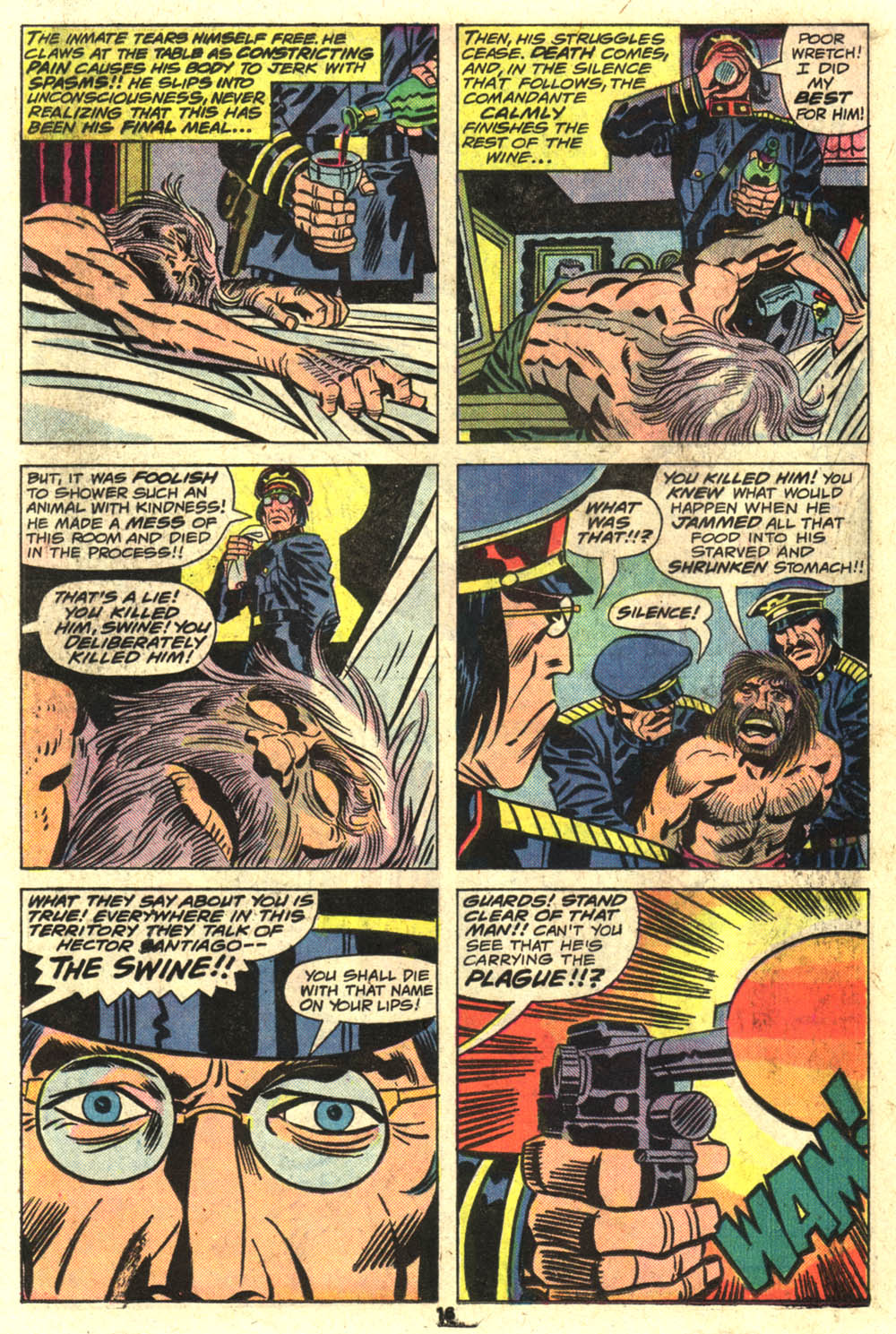

Still…I love Hob. I love him precisely because his presence in the film is so utterly, bracingly cynical. For most of the film, he embodies our hyperbolic fear and hatred of children; the preposterous inflated fear of a new generation of cynical pre-teen superpredators, the jaded youth terrifyingly familiar with vice. And then, in his death scene, when he’s no longer a threat, he becomes the perfect, heart-tugging victim. The film’s view of Hob turns on a needle from paranoia to pathos; from loathing to sentimental catharsis. There’s no attempt at connective tissue; no effort to make Hob a character beyond the tropes. He’s just Childhood Monster or Childhood Victim. There’s not even a pretense that he’s anything else.

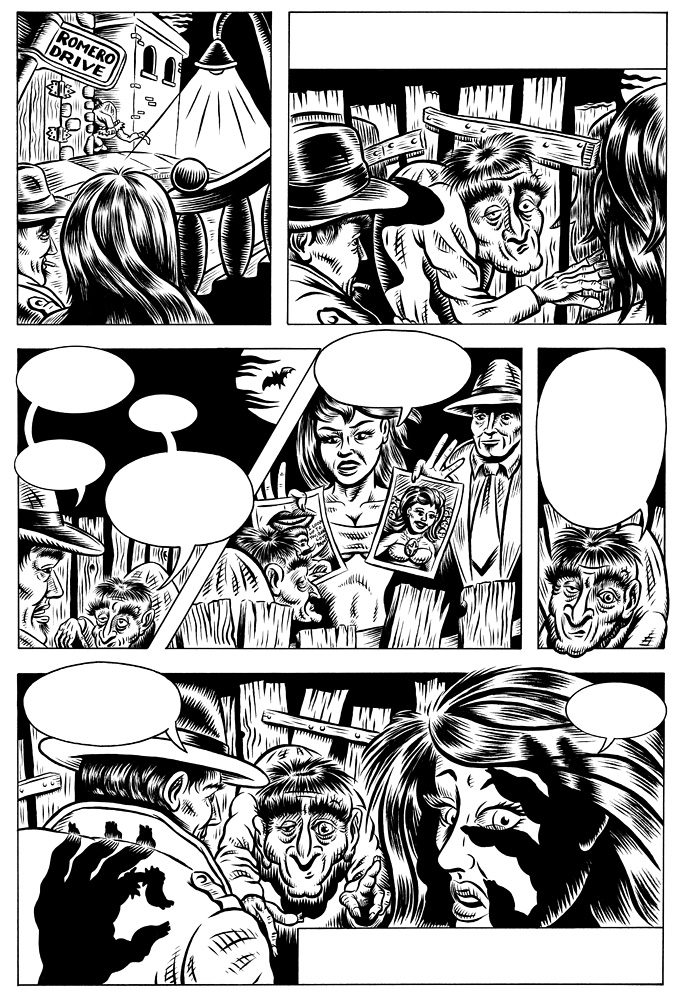

I don’t know whether Hob is intentional satire, gleeful hyperbole, or sincere fever dream. Probably a little of all of those, if the scene with the pre-teen Little League team and their coach robbing a store is any indication. But whatever the motivation, the result comes across like a sardonic, giggling sneer at every Hollywood film that has ever whipped up moral panic about teens, or dropped a dead child onto its protagonist in the name of Real Emotion. From the bad news kids breaking jazz records in Blackboard Jungle to the kidnapped youngster motivating a tearful Tom Cruise in Minority Report, all the children on screen, everywhere, start to look like Hob. And suddenly you wonder, do we even care about these kids? Or do we just get our kicks by pretending that they’re nightmare demons, innocent angels, and/or both at once?

Roger Ebert adored Minority Report, dead kid and all, and Millenial think pieces continue to dot the Internet. If you use racial or gendered or homopohobic stereotypes, there’s at least a decent chance someone will point them out. But kids aren’t seen as a marginalized group, and tropes around them aren’t seen as invidious, or just aren’t seen at all. Kids really are innocent victims, right? Or else they really are dead-souled thugs in training who need to get off my lawn.

Robocop 2, though, takes up the difficult task of exploiting childhood so blatantly that you can’t look past it, even if you’re determined to set your eyeline a foot over Hob’s head. Robocop 2 presents a dystopic future in which we hate and fear and condescend to children, just like we do now, just with a little less hypocrisy.

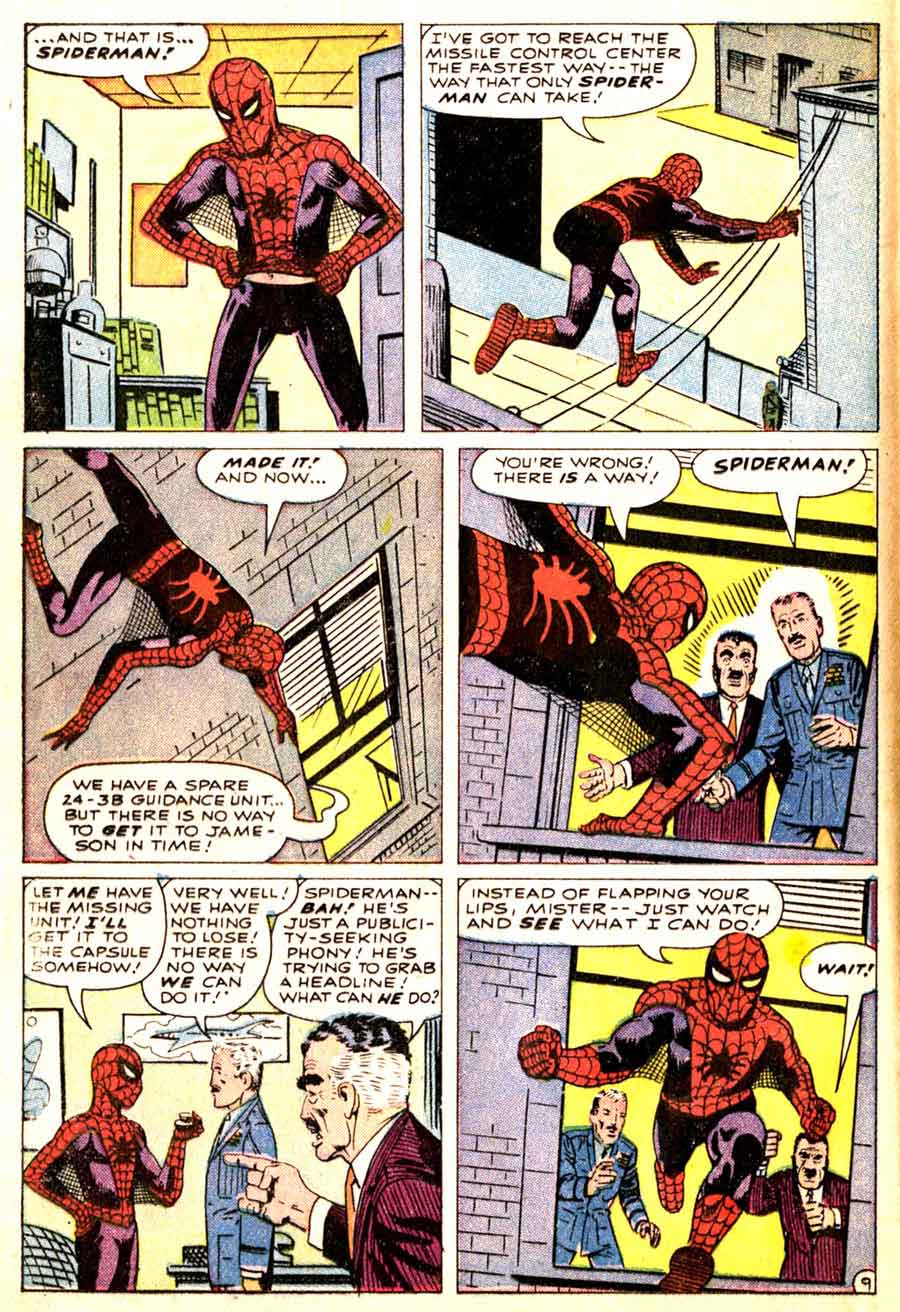

.jpg)

.

.

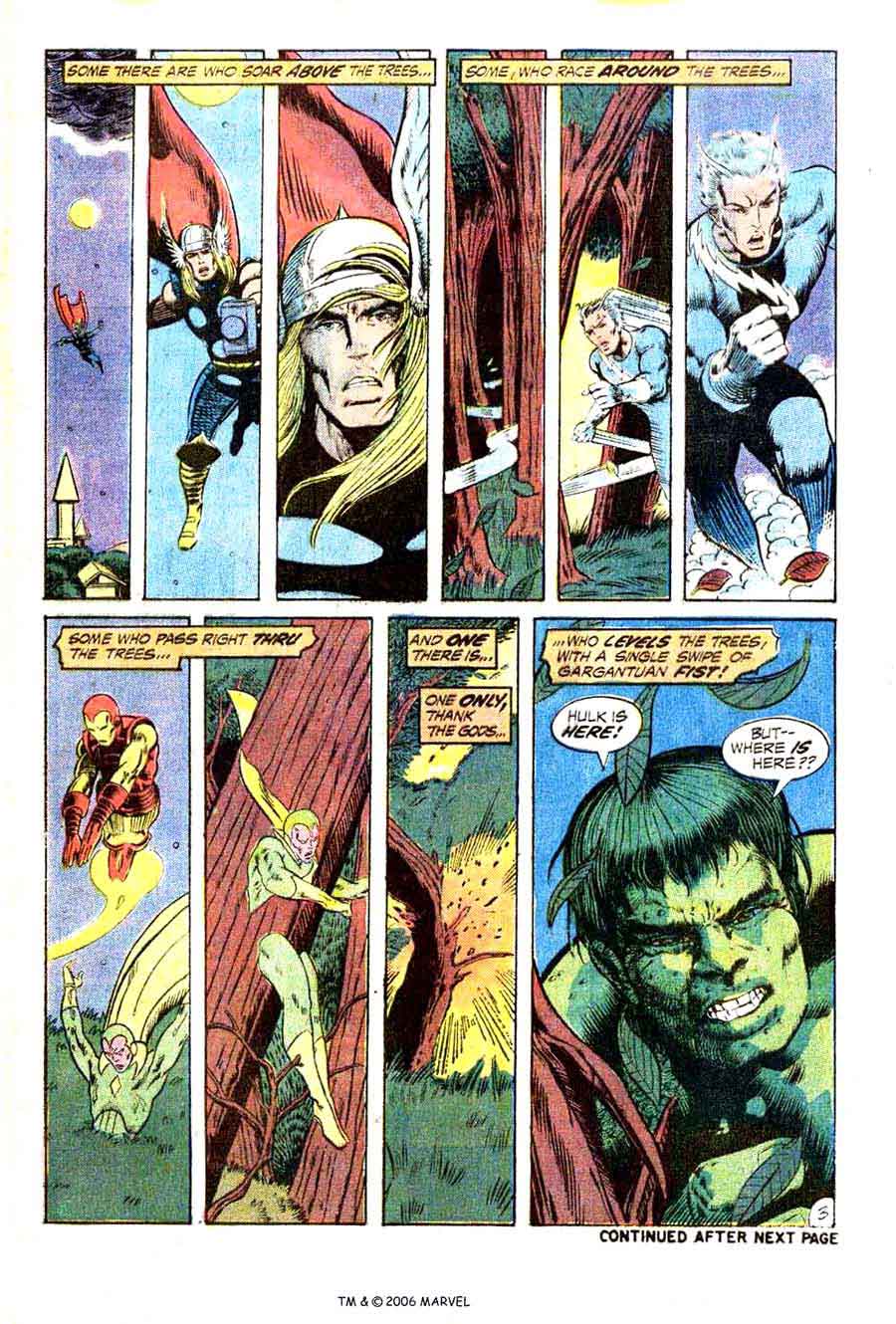

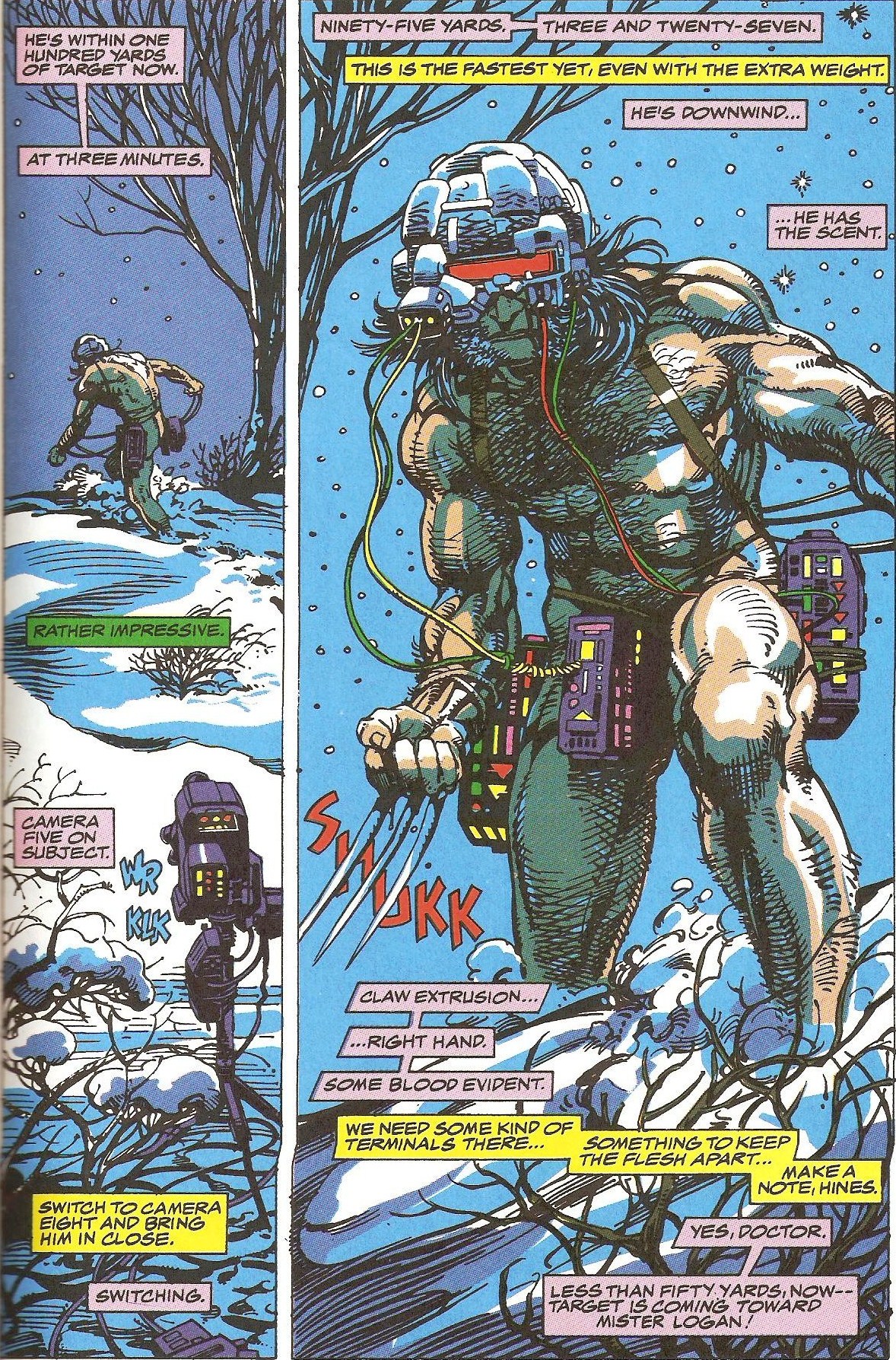

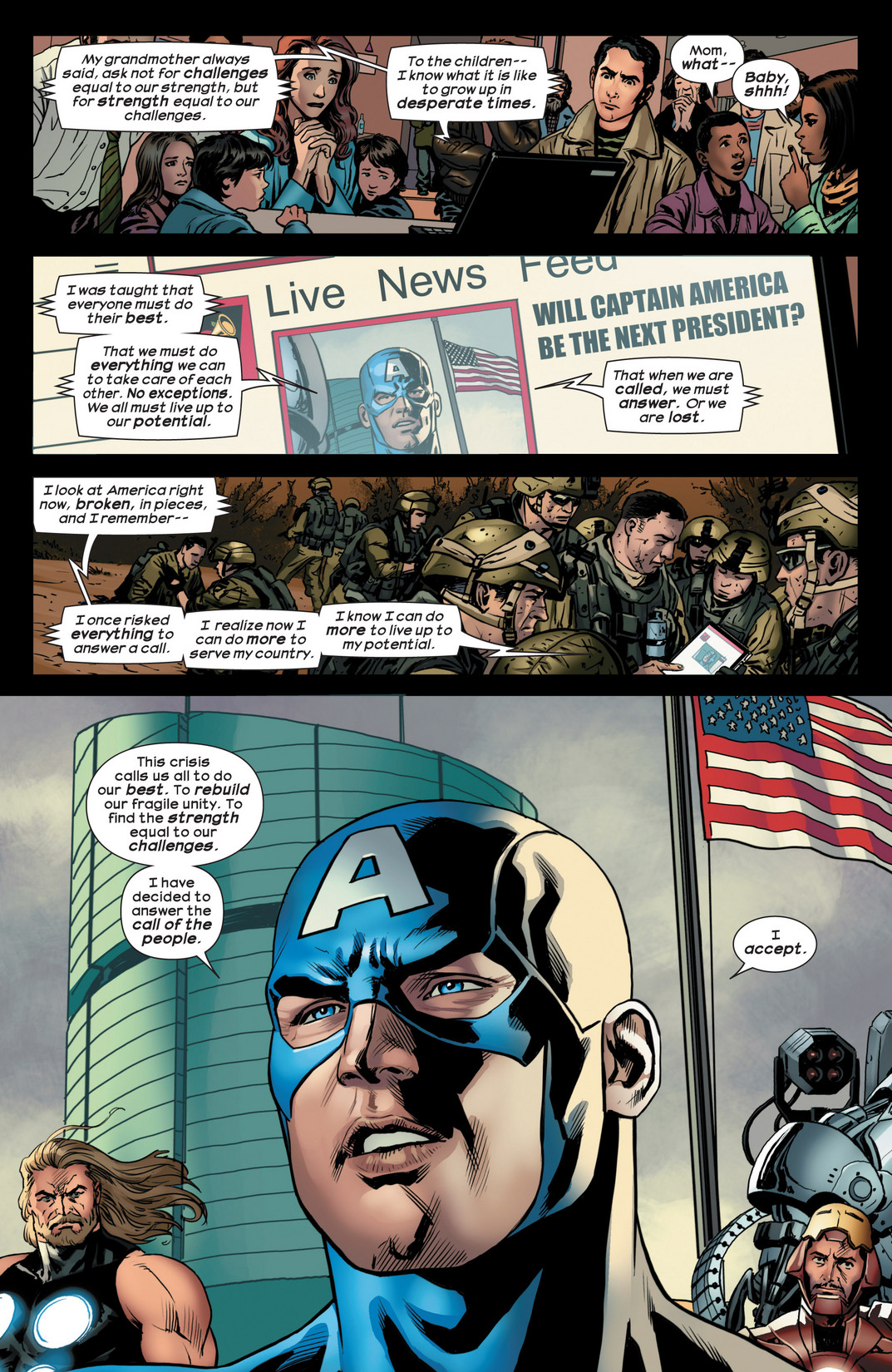

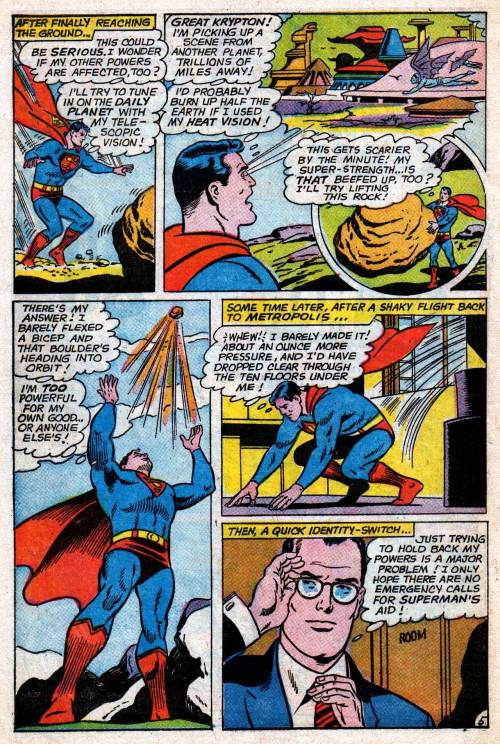

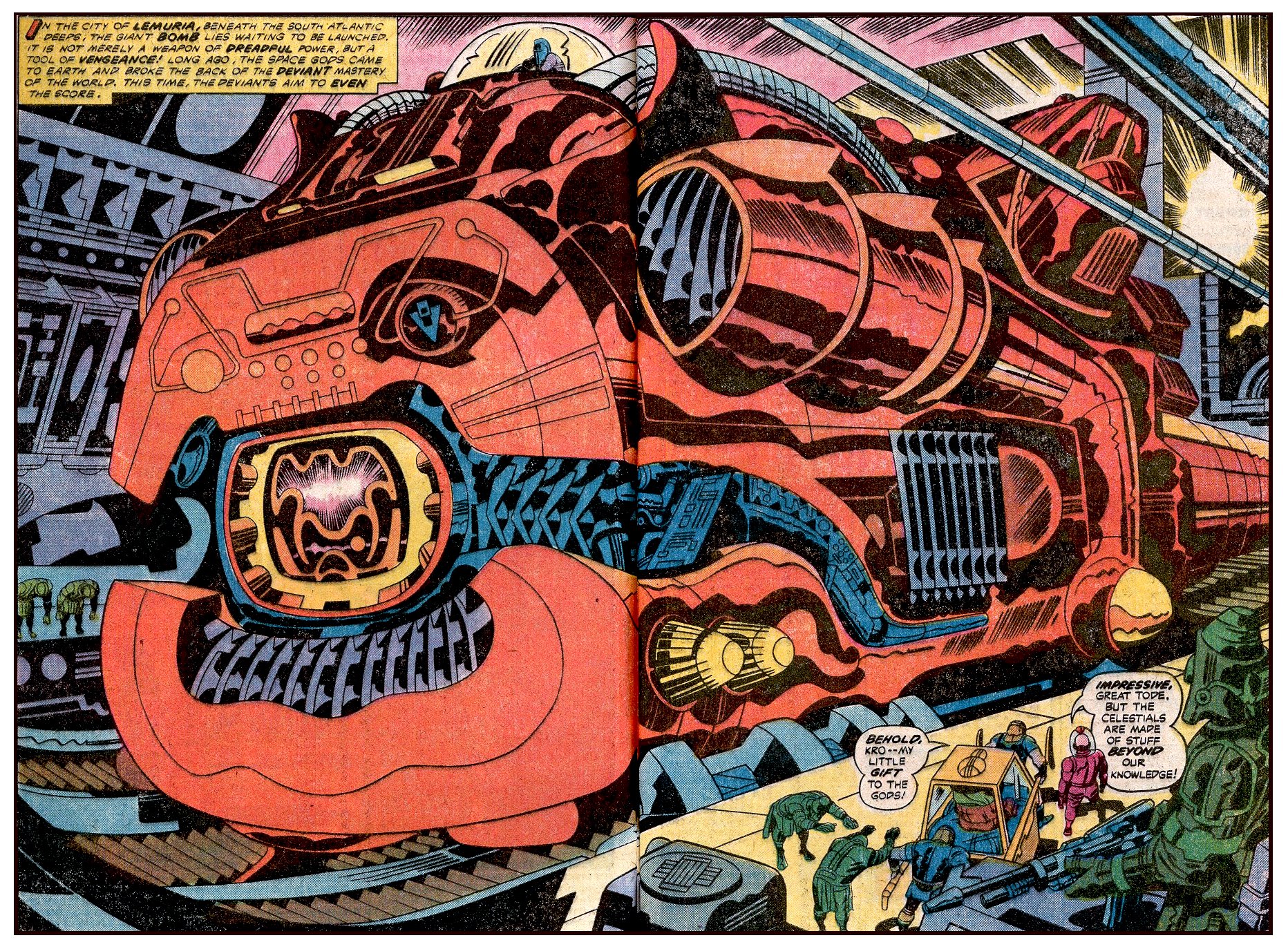

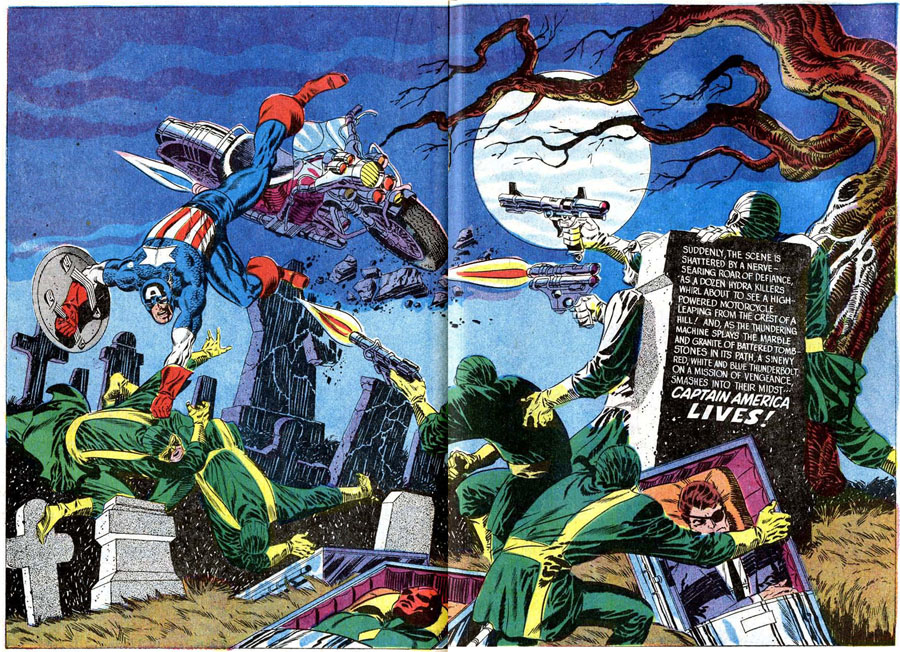

S(5dhqryzjtk4qcdgjv1lbpdjy))/superhero-library/Img/Pages/A1/A1-174-page-004-l.jpg)

S(5dhqryzjtk4qcdgjv1lbpdjy))/superhero-library/Img/Pages/A1/A1-174-page-003-l.jpg)