In a footnote in The Political Unconscious, Frederic Jameson quotes Edmund Husserl on “the constitution of Galilean science as the repression of praxis (italics mine).” Husserl says, “The geometry of idealities was preceded by the practical art of surveying, which knew nothing of idealities.” And thus, a tangible practice of mapping is rendered abstract when applied to the heavens– unclean knowledge is hermetically purified through contact with the infinite. In something of a Galilean move, Alain Badiou has, following Hegel, insisted that the tangible knowledge of science is not merely expressed though but fundamentally rooted in abstract interaction. He has sought to press this point in meditating on set theory mathematics, arguing against the idea of a “dissemination” that would atomistically reduce everything in a certain “world” to autonomous monads or particles, a common core or a higher singularity, any essential element that would point outside the structured relationships between related objects, relationships that resist being collapsed together in any reconciliation.

In reviewing Badiou’s Number and Numbers, John Kadvany quotes Badiou arguing against transcendent unity: “Dissemination, when it is applied to a natural multiple, delivers only a ‘shard’ of that multiple. Nature, stable and homogenous, can never ‘escape’ its proper constituents through dissemination. Or: in nature there is no non-natural ground.” But, by his own logic, Badiou cannot define his system from within that system. Notes Kavadny, “Set theory relies on first-order logic; it isn’t expressed through its own ontological language or other angelic media.” “You can study the higher infinite all you like for aesthetic or intellectual reasons,” states Kavadny, “but it can’t be justified by an ideology of natural scientific need.” The hubris Badiou attributes to reductionist analysis reappears in his own dream of pure autonomous immanent induction.

The problem of positing a symbolic system with its own symbols resonates with the distrust many feel in regard to Freud’s fixation (if you will) on castration. This literalizing of abstraction informs Lacan’s critique of the Freudian mother-child dyad of the oral stage (discussed by Lacan in terms of the register he calls Imaginary), and, in turn, of the classic three-part Oedipal disharmony and the Symbolic conflict of the genital drive– mother, child, and father. The point being that there is no pure time without the father, and neither is a pure sublimation offered by the irruptive introduction of the father. Lacan offers the phallus, an abstract signifier divorced from the physical penis, as an element haunting the relationship of mother and child, and as an element that does not disappear with the advent of the paternal Law.

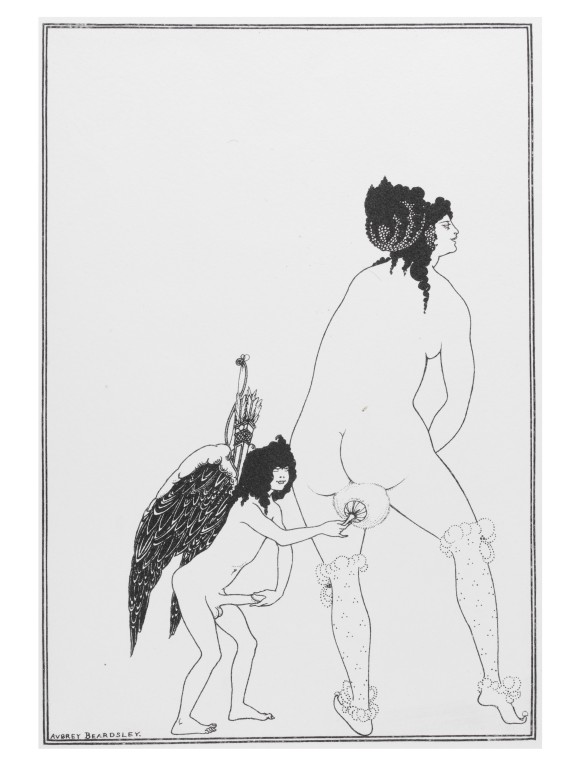

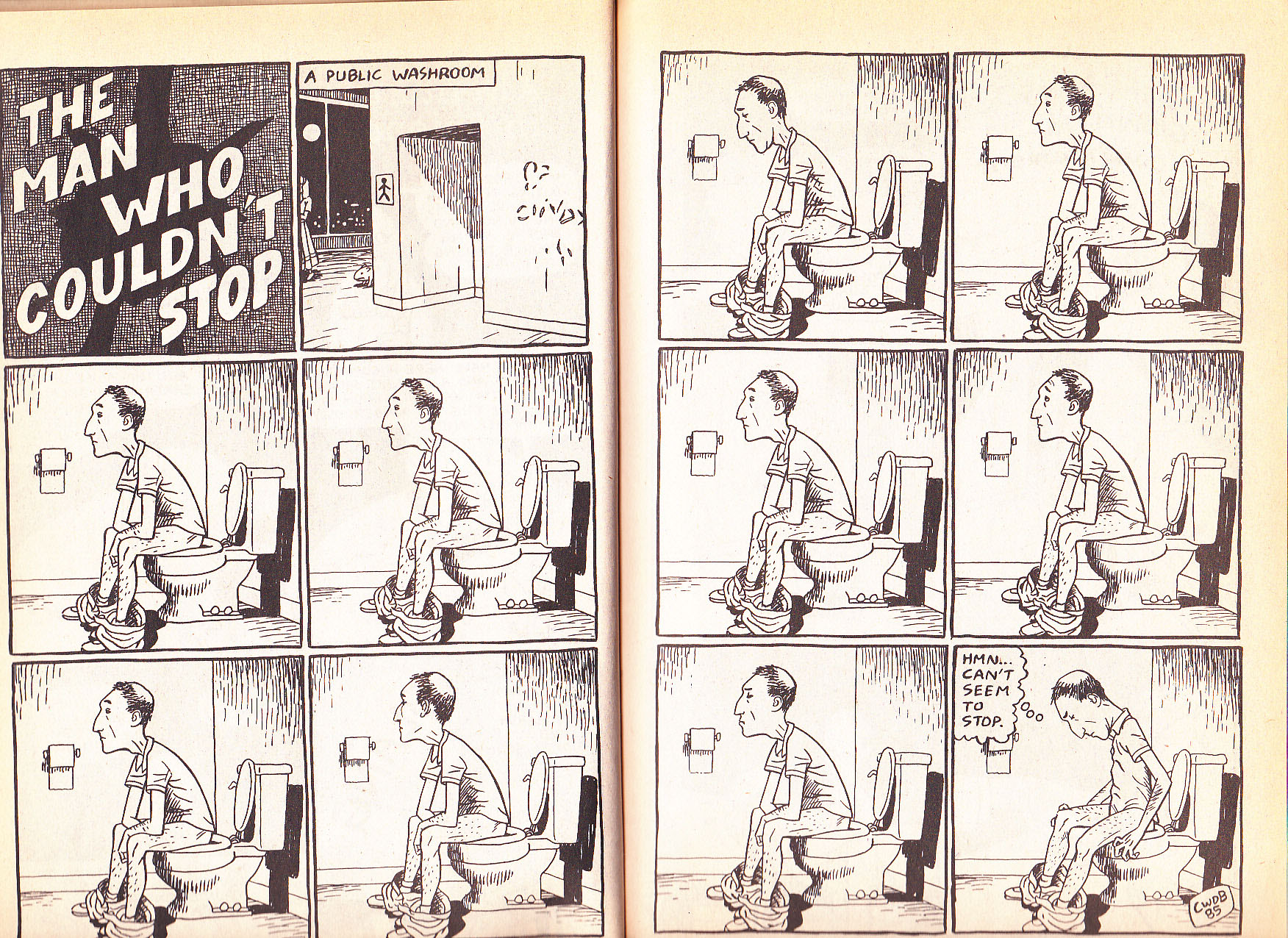

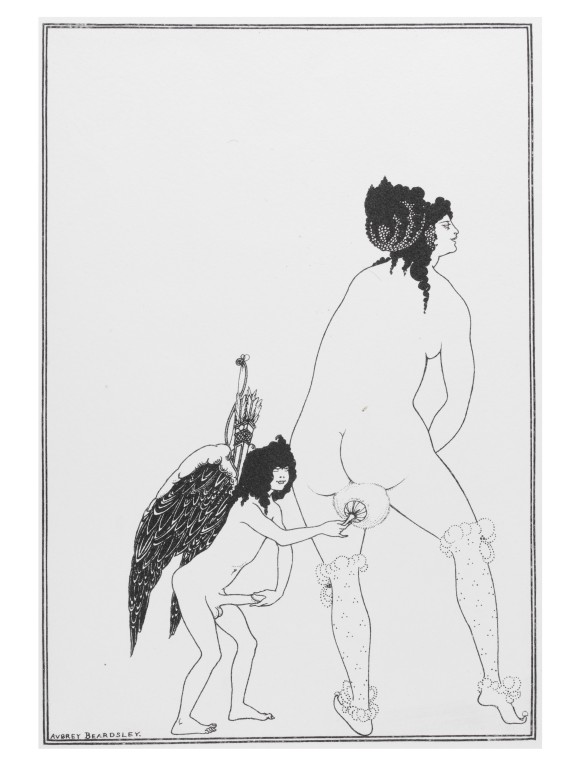

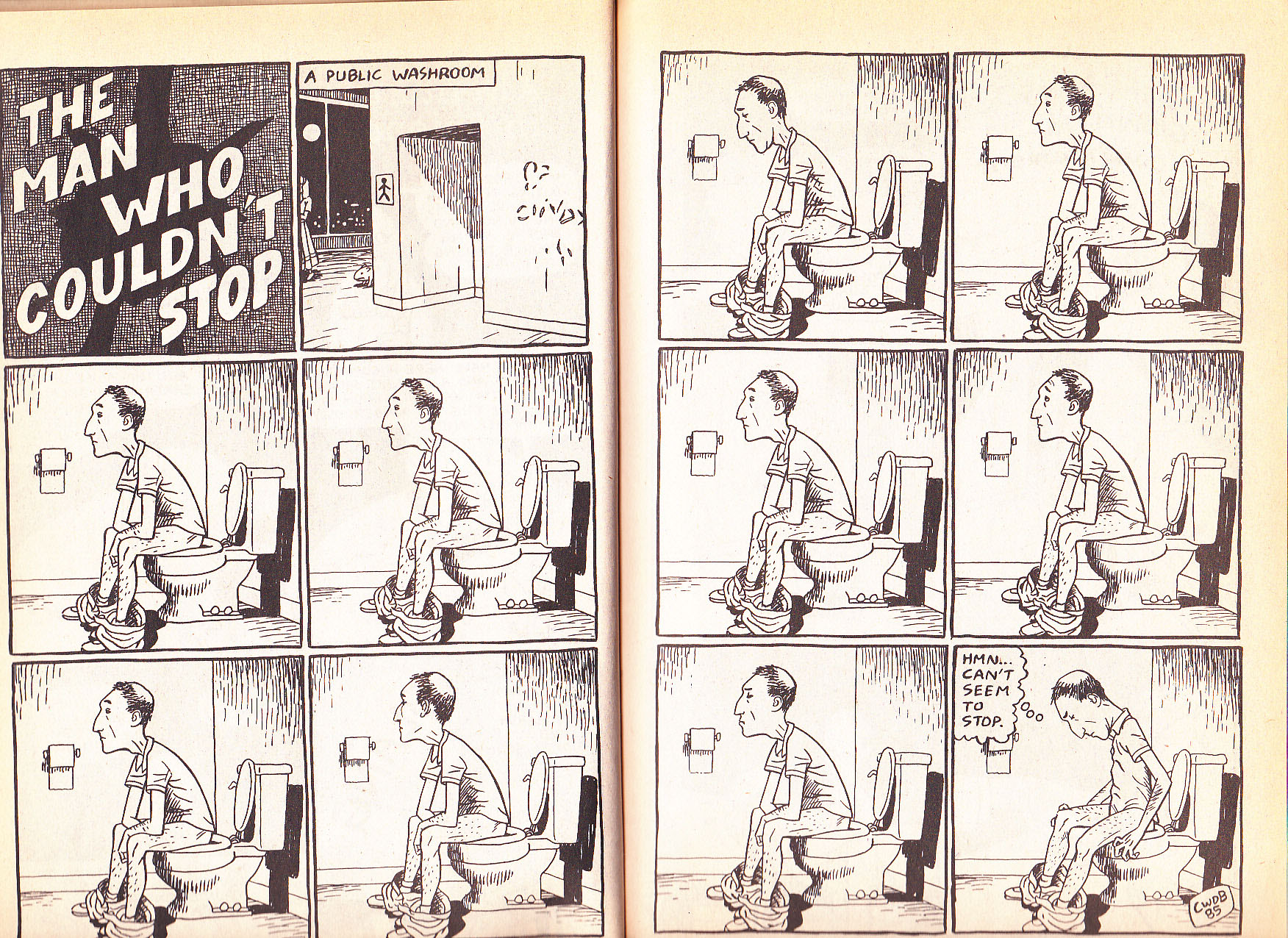

But this pair, the “romantic” dyad and the “comic” triad, still leave out a third term. In Freud’s introductory lectures on psychoanalysis, from 1916-1917, he talks of the fact that not only the penis can fill the symbolic function of the phallus, but so can the breast, as can the baby itself, as can feces. Our first creation, abjectly inhuman, an unclean expression of our interiority, feces define our ability to control our own bodies and thus the bodies of others. In a world that we imagine to be completely of and for material use, shit has become not only that which we create, but that which constitutes our value. In Marx, the paradigmatic anti-individualist, we see the apotheosis of voluntarism: a world in which existence is to be understood exclusively as effort. The modern human ideal is the vitalist worker/innovator endlessly shitting out product/algorithim, much like the character in Chester Brown’s comic book Ed the Happy Clown whose infinitely prolific anus is a portal to another dimension.

Analyzing sodomy in Shakespeare’s sonnets, Richard Halpern connects creativity and sublimation to the obsessive anus via Lacan’s alien yet ideal Thing, the lack which is the motivation of unconscious desire, the fetish to which fixation constantly returns.

Let not my love be called idolatry,

Nor my beloved as an idol show,

Since all alike my songs and praises be

To one, of one, still such, and ever so.

…One thing expressing, leaves out difference.

…And in this change is my invention spent(.) (Sonnet 105)

This singular emptiness is at the center of the Real; the Symbolic, the Imaginary, and the inexpressible Real make up the Lacanian triad that matches up respectively with Freud’s genital, oral, and anal stages. What Halpern terms “Shakespearean homosexuality” is “not identical with sodomy but results, rather, from aestheticizing the theological categories that construct sodomy”– i.e., as an impure act based on an unnatural preoccupation. This occurs in much the way that Paul appropriates official imperial Roman language to talk about the Kingdom of God.

And, as with discussions of the religious or aesthetic ineffable, “(s)odomy subsists as the speaking of the unspeakable, as the topos of the inexpressible or unnameable.” Not just in the sense of the closet, or “the love that dare not speak its name” (although those tropes resonate in the Sonnets), but an act of creation and awe, an intrusion of sublime artifice that Halpern associates with idolatry, but dissociates from the genital. Thus the fascination for and suspicion of artistic or divine creation from nothing:

And for a woman wert thou first created

Till nature as she wrought thee fell a-doting

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing. (Sonnet 20)

The iconic unspeakable sign is the remainder of purifying alchemical sublimation, the supplement of the phallus or the abjection of feces. Halpern finds an analogous (if arguable) link in the first chapter of Paul’s letter to the Romans, reading idolatry as a punishment for homosexuality among the Greeks. “But,” Halpern says, “this means that homosexuality, as a failure of natural vision, mimics that transcendence of nature which the Greeks otherwise fail to achieve.”

Reminiscent of Julia Kristeva’s abject womb, Halpern returns to passages in Shakespeare that connote decay and perversion. He links the “reeking” breath of the Dark Lady in the later sonnets with the Marquis de Sade’s repulsive misogynist description of Therese, of whose anus “we have proof positive that the shit of her infancy yet clung there.” Halpern goes on to propose a kind of violence and repetition in both the Renaissance and Enlightenment texts that can be linked with an abject negativity that provides new ways of figuring the sphincter-like prison of reality– I would identify in this the collective activity of the drives that Freud termed the “death drive.” In examining this excessive aspect of “doting” nature, we are led to a category of the anal that psychoanalysis has commented upon repeatedly, that of sadism.

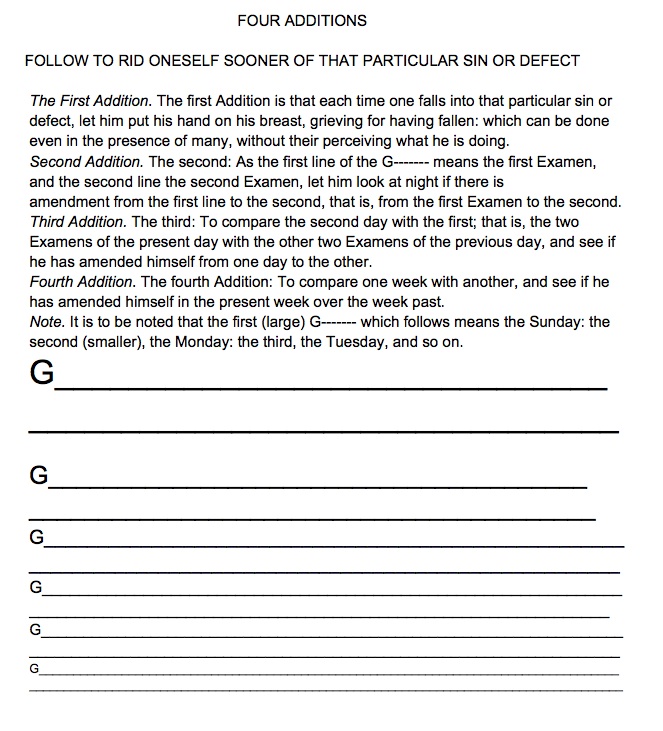

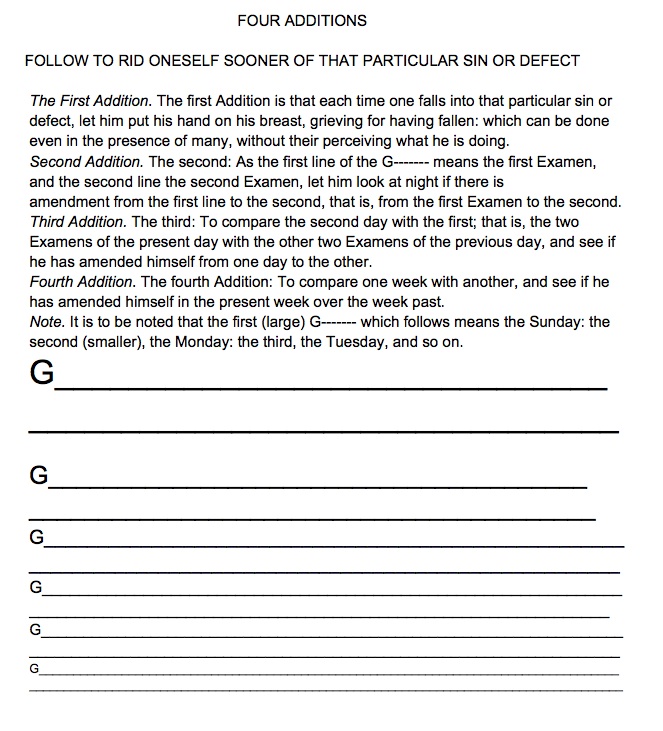

The death drive that returns insistently to the tight spot of unbearable pleasure is the scene of the utopian “languages” described by Roland Barthes in Sade Fourier Loyola, a book about authors whose systems, like Badiou’s, prescribe a discipline rather than a summary. In speaking of the lack of clear images in the Spiritual Exercises, Barthes says that St. Ignatius’ techniques “determine less what has to be imagined than what it is not possible not to imagine– or what is impossible not to imagine.” But the goal is not wordless beatitude. The anal-retentive “totalitarian” articulation of every imagined detail resonates with the immanence of structuralism; for Loyola, “language is his definitive horizon and articulation an operation he can never abandon in favor of indistinct– ineffable– states.” The infinite horizon of mathematical repetition in Loyola is captured well in the very first week, when he literally employs a diminishing character size when proscribing proper purging of a sin from the conscience:

Finally, however, the near-impossibility of achieving perfect purity is not an excuse to dismiss the idea of perfection. This perfection is outside of our world, and must be sought through helplessness. It must remain unknowable. This problem is graphically described by Jesus throughout the Gospels, but perhaps never with such clear anal overtones as when he insists in Matthew 19:24 that “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than it is for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” Money as feces was one of Freud’s least ambiguous metaphors, the thing you certainly cannot take with you when passing through a needle.

The increasingly abstract market of drives, and the increasingly abstract disciplinary father, for all their dispersed ephemerality, cannot pass into perfection while remaining what they are. The attempt to approach truth without “exhausting oneself,” as Barthes puts it, is the arrogance of attempting to create a perfected, purified immanence: a light without shadow, or an image without an observer, as when Galileo and Badiou forsake transcendence in the name of abstraction. Badiou’s attempt to use the fathomless infinity of set theory as a bedrock of Being is a primal fantasy of anal control that attempts to police boundaries and define differences, not by making them concrete, but by making them untouchable. Grasping this seductive (feminine) Real of jouissance is no more possible by repetition than by reduction. Nature cannot be conceived (of) without an unnatural element, a framework of artifice, but that artifice must emerge from a tiny, empty space beyond.