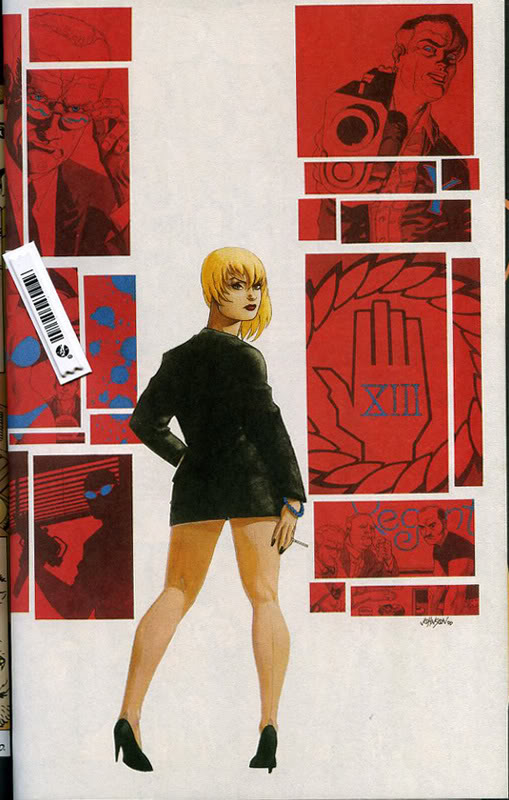

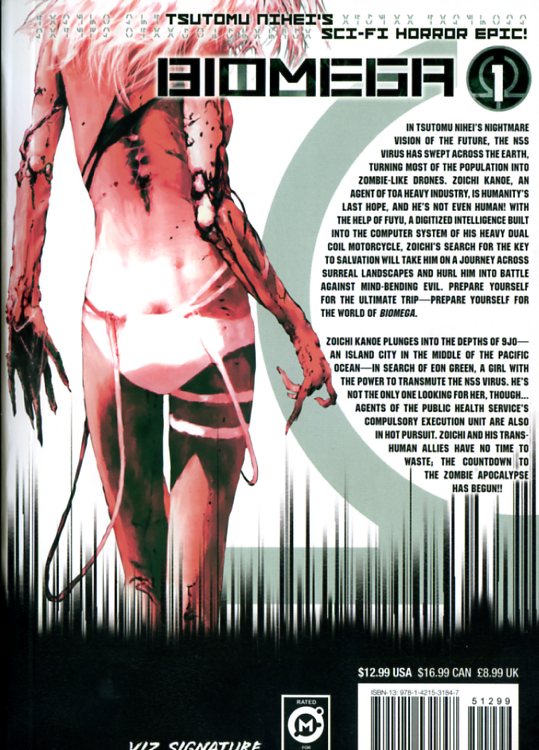

This post first appeared on Splice Today. Illustration from threadbombing.com.

______________

Right-wing heartland Republicans may believe in it, but it’s the left that truly loves creationism. Political outrage is fine, but everyone has to acknowledge at least to some small extent that sentient humans can differ on how often we should drop bombs on Afghanistan or when and whether women should have access to abortion. But creationism? That’s an argument about facts, not morals. It’s the ultimate proof that all those Red State yahoos are not just cruel, heartless bastards, but are congenitally, intentionally and hopelessly stupid. If the right lives to accuse their enemies of immorality, the left lives to accuse theirs of idiocy—and nothing screams “idiot” like looking at a Tyrannosaurus and trying to figure out how it could’ve fit on the ark.

Liberal attacks on creationists have, therefore, a unique note of barely restrained glee and purified contempt. Katha Pollitt’s recent essay in The Nation is an apt example of the genre. Riffing off a recent poll showing that 46 percent of Americans are Creationists, she vaults enthusiastically to the conclusion that almost half of her fellow citizens are actively and dangerously mentally ill.

“… rejecting evolution expresses more than an inability to think critically; it relies on a fundamentally paranoid worldview. Think what the world would have to be like for evolution to be false. Almost every scientist on earth would have to be engaged in a fraud so complex and extensive it involved every field from archaeology, paleontology, geology and genetics to biology, chemistry and physics. And yet this massive concatenation of lies and delusion is so full of obvious holes that a pastor with a Bible-college degree or a homeschooling parent with no degree at all can see right through it.”

The vindictiveness in that last sentence is especially nice. Obviously, if you don’t have a degree from an elite institution, you must be a fool. Certainly, you shouldn’t dare question the scientists. After all, the best research suggests that only 10 to 20 percent of them have been involved in or witnessed research fraud. What’s not to trust?

For what it’s worth, I think evolution is true; I believe in it as much as I believe in the Internet or in the existence of Katha Pollitt. I did my MA thesis in part on Darwin, and I’ve read a good deal of evolutionary theory for a layperson. I agree with Pollitt that creationism is incoherent and illogical. The earth is really old; dinosaurs existed long before people did; I’m related to apes, and have the hair growing on my ears to prove it.

However, I don’t think you have to be a fool to believe the contrary. Really, all you have to be is human. Humans, of whatever creed or politics, believe lots of things that have no particular scientific basis. Some people believe in ghosts. Some people—even some left-wing people—believe vaccines cause autism. Some people, again, some of them left-wingers, believe John F. Kennedy’s assassination was part of a vast conspiracy. Some people believe that Kennedy was a good President. Some people believe that economists can forecast the economy.

All of these beliefs have more practical negative consequences than a belief in creationism. In fact, the only real effect of creationism, as far as I can see, is to interfere with the teaching of evolution in some secondary schools. And given how lousy U.S. high schools are, this is probably a boon for science. As a former educator, I can tell you that the best way to get students to know nothing about a topic is to teach them about it. If you want to kill creationism as a viable public ideology, just make it a nationwide curricular requirement. “Adam was married to (A) Eve (B) Steve (C) a dinosaur (D) a platypus.” I’m sure given just a little time and the usual level of resource allocation, our educational system can insure that less than 46 percent of students will pick A.

Pollitt mentions the possibility that people just say that they are creationists for cultural reasons, rather than because they’ve studied, or even thought about, the science. But she doesn’t mention her own cultural interests or predilections. She claims she’s pointing out the dangers of the ideology, but it’s not like her article includes any scientific evidence that creationism is damaging. All she’s really got is theory, innuendo, and a few pitiful quotes from troubled scientists who mumble that disbelief in the scientific method is “very troubling.” In response to which I’d just point out that many scientists think the scientific method is horseshit. Again, science education in the U.S. is terrible, like all other kinds of education. There’s a discussion to be had about that, but it has little if anything to do with creationism.

Pollitt’s article, in other words, is basically dishonest. She says she’s talking about creationism to alert us all to the harm it does. But really it seems like she’s saying creationism causes harm in order to give her an excuse to talk about it. The poll isn’t a wake-up call. It’s just another way to sneer at people she doesn’t like for the horrible sin of being different—more religious, less educated—than she is.

I wish my fellow citizens would vote for single-payer healthcare; I wish they’d get rid of right-to-work laws; I wish they’d embrace legal marijuana and stop supporting wars. But creationism? I’m sorry, but if we woke up tomorrow and everyone suddenly believed in evolution, the world wouldn’t be one jot better than it is today—except maybe we’d be spared the self-congratulatory liberal concern-trolling on the subject.