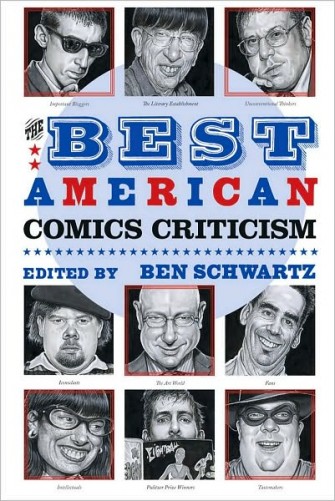

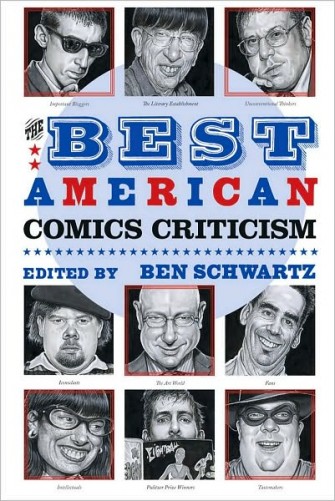

Hate fest is over, but hate is ever new. So I thought I’d reprint this review of Ben Schwartz’s Best American Comics Criticism which I posted at tcj.com a while back. The piece was part of a roundtable: you can see all the other pieces at the following links:

Opening contributions from Ng Suat Tong, Noah Berlatsky, Caroline Small, Jeet Heer, Brian Doherty and BACC editor Ben Schwartz; responses from Caroline Small, Ng Suat Tong, Jeet Heer, Noah Berlatsky and Ben Schwartz.

My review is below.

_____________________________

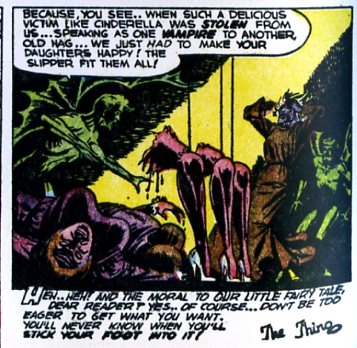

Ben Schwartz begins his introduction to Best American Comics Criticism with an anecdote: one day at a mall he heard two young girls arguing about what to call graphic novels. For Schwartz, this was a “definitive moment.” Comics used to be for nebbishy, perpetually pubescent, socially stunted man-boys — but that’s all over. Superheroes are dead, replaced by the teeming offspring of anthropomorphic Holocaust victims. Nowadays everybody from New York Times editors to real live tweens are enamored of the sequential lit. From a niche product for mouth-breathing microcephalics, comics have become our nation’s primary containment vessel for deep meaningfulness. Open them and feel your world expand.

But while comics may have generously embraced tween mall rats, the same cannot exactly be said for The Best American Comics Criticism. Schwartz’s keyboard lauds the heterogeneous appeal of comics, but his heart is still in some back alley, cheeto-smelling direct market basement, lost in a rapturous fugue of insular clusterfuckery. You’d think that if you were editing a tome focusing on comics criticism over the last 10 years, and if you further began your tome by genuflecting towards tween girls as icons of authenticity, you might possibly feel it incumbent upon you to include some passing mention of the 1,200 pound frilly panda in the room. Not Schwartz though; if he’s ever heard the word “shojo,” he’s damned if he’s going to let on. The only manga-ka who defiles these pristine pages is alt-lit analog Yoshihiro Tatsumi — and he only makes the cut because he was interviewed by that validator of all things lit-comic, Gary Groth.

The almost complete omission of manga (and the complete omission of online comics) isn’t an accident. Schwartz deliberately set out to produce a work which would appeal only to his own tediously over-represented demographic which would focus on the triumph of lit comics over the years 2000-2008.

Now, you might think that it takes a certain amount of chutzpah to title your book Best American Comics Criticism and then, deliberately collect a sampling of essays related to one particular strand of comics that happens to interest you and your in-group. You might think that in these circumstances your title seems, not like a description of the contents, but rather like a transparent marketing ploy. You might think that craven, and I would agree with you.

It’s only once you get over the fact that the book’s cover is a lie, though, that you can really start to appreciate the purity of the work’s cloistered lameness. Yes, only one female critic (Sarah Boxer) is included. Yes, Schwartz compulsively returns to the same writers again and again — three essays by Donald Phelps, two pieces by Dan Nadel, two by Jonathan Lethem, two by Dan Clowes. And yes there are not one, not two, but three interviews by Gary Groth, the book’s erstwhile publisher. But the most audacious moment of collegial nepotism is a pedestrian essay about Harold Gray by — Ben Schwartz himself! Even better, if you read the acknowledgements you learn that Schwartz wanted to include another of his own essays, but was prevented by rights conflicts. Really, it’s kind of a wonder he didn’t just put together a book of his own writings and slap that Best American title on it. After all, he’s the editor. If he thinks Ben Schwartz writes the best criticism in explored space, who’s to gainsay him? (It’s possible that Schwartz wanted to include the other essay instead of the piece he used… which means that he printed his second best as one of the top essays of the decade. If that hadn’t worked, would he have gone to his third best? His tenth? His grocery lists?)

To be fair, I’ve actually quite liked some of Schwartz’s writing over the years. A piece by him about Paris Hilton which ran in the Chicago Reader is one of my favorite things to ever run in that publication — I still remember its concluding paragraph clearly seven years later. And while using multiple essays by a handful of writers seems like a gratuitously ingrown way to structure a best-of book, if the results were provocative and enjoyable, I wouldn’t kick.

Unfortunately, the results here are… well, they’re really boring, mainly. Part of the problem is, again, the insular air of self-satisfaction. The worst in this regard is probably the Will Eisner/Frank Miller interview excerpt, in which the participants both pat themselves on the back so vigorously that they seem to be in some sort of contest to see whose arm will fracture first. In terms of abject sycophancy, though, the David Hajdu interview with Marjane Satrapi is close behind. “Like her work, Satrapi’s apartment is a mosaic of Middle Eastern and Western, high and low — a willful testament to cultural and aesthetic heterogeneity.” What is this, Marie Claire? Compared to such celebrity puff-piece drivel, the merely grating mutual admiration on display in the Jonathan Lethem/Dan Clowes interview seems positively tolerable. Sure, Lethem actually claims that what he and Clowes are doing is somehow “dangerous” while they’re both sitting on a podium in front of a herd of maddened, man-eating elephants — or are those rapturously respectful undergrads? Either way at least he doesn’t opine that Clowes’ bow tie is a sartorial sign of nostalgic doubling. You take what you can get.

When the book isn’t oozing complacency, though, it’s giving off an even worse miasma — anxiety. As any alt comics confession will tell you, the clubby smirks of the knowledgeable hobbyist hide a desperate desire to be accepted. The book is one long grovel, as if Schwartz hopes to win fame, fortune, and mainstream acceptance through sheer power of toadying. This is most visible in the egregious reliance on “name” authors. Ephemeral book introductions by John Updike, Dan Clowes and Jonathan Lethem all read like exactly what they are — celebrity endorsements. Alan Moore’s disjointed interview transcription about Steve Ditko is interesting but slight, while Seth’s essay on John Stanley seems padded out with an overdetermined breezy musing that is, I guess, supposed to be redolent of whimsical genius. “I’m sure when [Stanley] wrote these disposable comic books he could never have dreamed that, half a century later, grown adults would still be looking at them. It’s an odd world.” Or maybe it’s a clichéd world. So hard to tell the difference.

Schwartz pulls out a host of other gimmicks too — a fascimile of the court decision giving Siegel and Schuster back their rights in Superman; an Amazon comments thread about Joe Matt; a meta-cartoon by Nate Gruenwald, comprised of annotations upon a fictitious old school cartoonists “classic” strips. The first seems needless, the second is blandly predictable; the last actually has a lovely expressionist/modernist feel, though I think it probably lost a good deal in being excerpted. All of them, though, seem to come from the same place of nervous desperation. “I know no one here really wants to read criticism,” Schwartz seems to be saying. “So, um… here! Look! Bunnies!”

Schwartz does seem to prefer bunnies to criticism — perhaps because he has only the vaguest idea of what criticism is, or of why anyone would be interested in it. Specifically, for a critic and a supposed connoisseur of criticism, he seems to have a marked aversion to anything that might be considered an idea. Most of the pieces in the book say little or less than little. John Hodgman’s essays, for example, tells us that Jack Kirby thought of his Fourth World series as a long completed work… and now folks like Brian K. Vaughn also think of their series as long completed work, and ain’t that something? Rick Moody says Epileptic shows “this relatively new form can be as graceful as its august literary forbearers.” R. C. Harvey assures us that Fun Home is “Serious literature for mature readers for whom sex is only part of adulthood;” Jeet Heer insists that “Whatever he might have drawn from his personal memories, the emotions that Frank King explored are universal;” Donald Phelps emits his usual fog of avuncular gush; Paul Gravett bounces up and down in the backseat while chattering on about how “lots of people, writers, artists, editors and readers, are in this for the long haul, for however long it takes for the graphic novel to achieve its possibilities.” This is knee-jerk boosterism, platitudinous bunk intended to sell me crap, not to make me think. For Schwartz, it seems, the best criticism is marketing copy. Maybe he should edit an anthology of beer commercials.

There are some enjoyable pieces. In his review of comics commemorating 9/11, R. Fiore sounds like the ignorant blowhard at the end of the bar (Terrorism doesn’t work, Robert? Really? The KKK will be surprised to hear that Jim Crow never happened then.) But at least he has some personality and something to say, no matter how asinine. Sarah Boxer’s essay about race in Krazy Kat has moments of interpretive élan. Ken Parille’s dissection of Dan Clowes’ David Boring is so passionate about its obsession that it’s fascinating reading even for someone who, like me, really hates David Boring. And Dan Nadel’s evisceration of the Masters of Comics art exhibit is perhaps the strongest piece in the volume, not least because it hits so painfully close to home. “So, if the curators really want comics to be examined as a serious medium, the first step is not to establish a bullshit canon, but rather to be serious — avoid silly stunt-casting, attempt to provide rudimentary information, and for heavens sake, try not to commission an exhibited artist’s wife to write about another exhibited artist. Y’know, act like real, grown-up curators! Good luck.” Schwartz, man — that had to have left a mark.

But a few pleasant oases don’t make it worthwhile to cross the wasteland. The irony is that, in the end, this book proves exactly the opposite of what Schwartz intended. Best American Comics Criticism doesn’t give us comics as an engaged, vibrant medium, connected to ideas and to the broader world. Instead, Schwartz’s comicdom is a cramped little shanty, from which, every so often, a tiny face sticks out to lick the nearest boot or shout in a quavering voice, “I am somebody!” before diving back into the hovel. If you believe this volume, comics between 2000 and 2008 went precisely nowhere. They’re still as boring, still as self-involved, and still as desperate for approval as they ever were. I don’t actually believe that Best American Comics Criticism is an accurate reflection of the best in comics or in writing about comics. But if it is, we all need to give the fuck up.