Erica Friedman did a post way back when on the Bechdel test. It prompted a fun comment thread, including a lengthy discussion by Melinda Beasi, which is reproduced below.

I’m glad you brought this topic back here after the conversation on Twitter. I think, in retrospect, why I reacted negatively to Mo’s personal taste being included as a criteria for the test, is that suddenly a test that I personally looked to as a guide for helping me find works I might enjoy (lists of manga, books, movies, etc. that fulfilled the letter of the test were popular when I was a regular on LJ) had essentially shut me out. Because while I always prefer stories containing strong female friendships and a significant female presence–the kind likely to emerge from following the letter of the test–by adding in Mo’s taste, nearly all the work I liked best was eliminated or at least deeply in question. So where was my list now? If the women I most identified with and most enjoyed reading about suddenly weren’t interesting enough for Mo, I felt thrown out along with them. It was as though after all the youthful years I spent being viewed by my peers as “not feminine enough” to be an acceptable girl were being followed up on with years in which I would be viewed as too girly to be an interesting woman.

Obviously, that’s an extreme (and inappropriate) reaction. Why should I care what Mo thinks of my books? I know why I like them and, whether she would read them or not, I gain strength and insight from the women within their pages. And it may be that I was simply mistaken to interpret the test as a guide for finding stories about women that might interest women. Perhaps it really is just intended to identify stories of interest just to women like Mo. So maybe what I’m really looking for is a different list. I, too, am interested in books where female characters are engaged with each other on issues other than the men in their lives. I think, though, that because the reality of my life differs so much from Mo’s, I’m looking for something a little different in my fiction.

I actually don’t think you’re wrong at all when you suggest that women are still socialized to be needy and that our fantasies are influenced by the expectations set up for us. This is our reality. This is my reality. So when I’m looking for characters I can identify with in manga, I’m going to find that in women who struggle with exactly those things.

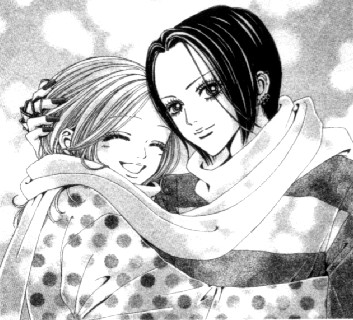

For instance, one of the characters I identify with most is Nana Komatsu (aka “Hachi”) in Ai Yazawa’s NANA. While I’ve got a career drive that better resembles her friend Nana Osaki’s, like Hachi, I can measure my past in increments of ex-boyfriends. I’ve struggled, as she does, with being hung up on men, with needing to feel loved (even when it’s false), with needing to keep my real thoughts and feelings secret for fear of losing that love, and so on. I’ve come further than she has (*maybe*, that’s probably more appropriately discussed over beer) but while she’s a woman Mo might find tiresome, she’s one *I need to read about*. She’s relevant to my life. Not the life I maybe wish I had, but my actual life. What I love about NANA is that while Hachi struggles with these things, what the real story is about is how, ultimately, the relationship that Hachi and Nana have with each other is more real and more satisfying than their tumultuous relationships with men. Do they talk to each other about the men in their lives? Certainly. They also talk about their careers, their personal hopes and fears, each other, and everything else under the sun. These women reflect myself back to me, but they also provide a blueprint for female friendship in which I can find hope and inspiration. I can’t undo the person I am or the broken things in my own past. I can’t erase the way I was socialized or what that made me. So for me, seeing that addressed on paper is important. It’s what makes something more than fantasy for me as a reader. And because so many women still struggle with these things daily, I think these stories are important as stories for women, if not perhaps as stories for women like Mo. In my world, these women are heroic.

All that said (and perhaps to get around to your actual point), Blindmouse’s recent Top 12 Fictional Female Friendships inspired me to try to put together my own list focusing exclusively on manga. But when I sat down to write it, I had trouble coming up with more than five. Though I could think of many, many strong, inspiring, heroic women in manga, I could think of just a handful who actually appeared together in the same story. Perhaps that should not have surprised me, but it really did.