This first appeared in the Chicago Reader.

_____________________

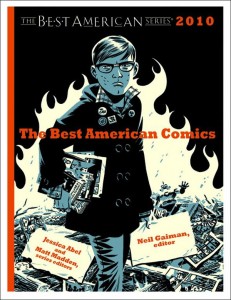

Neil Gaiman, who edited the 2010 installment of The Best American Comics, occupies a prominent but strange place in the history of the form. His Sandman series (1989-1996) was hugely popular and critically acclaimed. Although set in the traditional DC Comics universe—with walk-on parts for everyone from Hellblazer’s John Constantine and members of the Justice Society to obscure villains like Dr. Destiny—the book was original in tone and appeal. In place of steroidal underwear fetishists done up in primary colors Sandman offered pale, thin Dream, who wore somber contemporary or period garb and angsted rather than fought his way through unhurried, character-driven fantasy narratives, strewing portentous bons mots in his wake.

Neil Gaiman, who edited the 2010 installment of The Best American Comics, occupies a prominent but strange place in the history of the form. His Sandman series (1989-1996) was hugely popular and critically acclaimed. Although set in the traditional DC Comics universe—with walk-on parts for everyone from Hellblazer’s John Constantine and members of the Justice Society to obscure villains like Dr. Destiny—the book was original in tone and appeal. In place of steroidal underwear fetishists done up in primary colors Sandman offered pale, thin Dream, who wore somber contemporary or period garb and angsted rather than fought his way through unhurried, character-driven fantasy narratives, strewing portentous bons mots in his wake.

In short, Sandman was goth.

Superhero comics mostly appeal to guys who’ve been reading them since they were 12. Goth, as any Sisters of Mercy fan will tell you, often appeals to girls. Sandman offered enough pulp adventure to keep many young male readers—myself included—interested. But it reached beyond that fan base. As Best American Comics series editors Jessica Abel and Matt Madden note in their 2010 foreword, Sandman “single-handedly upped the ratio of women reading comics.”

Trouble is, Sandman only increased the number of female readers as long as those readers were reading Sandman. The book didn’t change the demographics of the industry as a whole. Though highly respected and popular, the series had remarkably little influence.

Certainly there were loads of Sandman spin-offs. DC has, following Gaiman, shown some interest in fantasy-oriented series—the currently ongoing Fables for example—and independent titles like Gloomcookie and Courtney Crumrin followed a goth-oriented, female-friendly path. But these efforts were marginal. Overall, post-1990s, the mainstream comics industry first drifted and then scampered towards massive, complicated stories mostly of interest to a male, continuity-porn-obsessed fanbase. Gaiman moved on to writing novels (notably, sophisticated fantasies like Neverwhere and Coraline), and the formula he created was largely ignored. Instead of creating goth comics for girls, American companies chose to stick with insular cluelessness and let the Japanese have the female audience. Manga comics, especially those aimed at girls, exploded in popularity here. And that, in case you were wondering, is no doubt why the Twilight comic adaptation isn’t drawn by homegrown artists like Jill Thompson or P. Craig Russell or Ted Naifeh but by Korean illustrator Young Kim, in a manga style.

Gaiman’s influence is weak even when it comes to Best American Comics 2010. One of the oddest things about the book is how little it has to do with its editor’s oeuvre.

I mean, yes, it’s possible to make connections between Sandman and some of the selections here. An excerpt from the lyrical The Lagoon, by Chicagoan Lilli Carré, plays on goth tropes and the meta-contemplation of storytelling in a Gaimanesque way. The dreamlike pacing, melodramatic romance, and kissing skeletons in Lauren Weinstein’s “I Heard Some Distance Music” might also be seen as at least elliptically referring to him. And the heavy-handed cleverness of a passage from David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp—a billboard advertising firmamint for diarrhea, for instance—points to one of the less appealing aspects of Sandman. A more positive echo can be found in the first selection in the book: an excerpt from Omega the Unknown by Jonathan Lethem, Farel Dalrymple, and Gary Panter that fuses superhero goofiness with literary smarts.

The American mangaesque style, arguably descended from Gaiman, is represented in a few places, such as an excerpt from Bryan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim vs. the Universe. Still, there’s nothing in this anthology that you can look at and say, “This wouldn’t exist without Neil Gaiman.”

That’s OK though. Sandman had some serious problems, one of the most prominent being the inconsistent, generic, and even shoddy work of some of its pencilers. The visuals throughout this volume are much more distinctive and engaging. Theo Ellsworth’s “Norman Eight’s Left Arm,” from Sleeper Car, sets crude figures against detailed natural backgrounds to create a look that’s half clip art, half woodcut—a lovely complement to his surreal tale of woodland creatures, weeping gnomes, and gambling robots. John Pham channels Chris Ware to create an elaborate, fractured board-game-like layout for his tale of despair and neurosis among spindly, cosmically marooned characters in a Sublife excerpt called “Deep Space.” Comics canon standbys like R. Crumb and Ware himself are represented with visually pleasing selections. And sometimes when the art isn’t so great—as in Dave Lapp’s charmlessly clunky “Fly Trap” or Michael Cho’s bland, text-cluttered panels for “Trinity”—there’s at least a consistent visual style.

Even when he makes awful choices, you’ve got to admire Gaiman’s eclectic enthusiasm for a comics world that has so little to do with him. I cordially loathe Derf’s nostalgic hagiography of punk rock. Peter Kuper’s indifferently rendered anti-Bush commentary is as vacuous as it is predictable. And one earnest account of a national disaster per book is fine—either Katrina or 9/11, please, but both makes it look like you’re straining. Still, I found it pleasantly disorienting to see all of the above clumped together under a single editorial imprimatur.

Of course, not-something-you’d-expect-Neil-Gaiman-to-like doesn’t really constitute editorial vision. Gaiman actually cops to the lack of coherence in his introduction, saying that what he likes most about comics is that it’s “a democracy, the most level of playing fields.” Foolish inconsistency is the point—a celebration of “the biggest secret in comics: that anyone can do them.” And yet there remains a curious lacuna in Gaiman’s collection. Critic Stephanie Folse (aka Telophase) picked up on it immediately. After reading the collection she e-mailed me to say that it ironically “reinforced that . . . I don’t much like slice-of-life stories, autobiographical fiction, surreality, or political ranting in prose or comics. . . . Escapism all the way for me!”

Personally, I like surrealism, and can make my peace with slice-of-life, autobiography, and political ranting in at least some contexts. But I get Folse’s complaint. There are lots of different kinds of comics represented in this book, but intelligent, imaginative, escapist Gaiman-esque pulp for all genders isn’t here.

Maybe it’s the nature of the project. The Best American Comics series aims for a literary bookstore audience. Still, if you’re going to invite Neil Gaiman to be your editor, it seems like you might sneak in a few pieces for his fans, however scarce that kind of work is these days. Gaiman’s Dream wasn’t perfect, but he did have a dark, melancholy charm. It’s sad to see him abandoned so utterly that even his creator seems barely to remember him.