This first appeared on Comixology.

_________________

Narrative entertainment for guys tends to come in two broad categories.

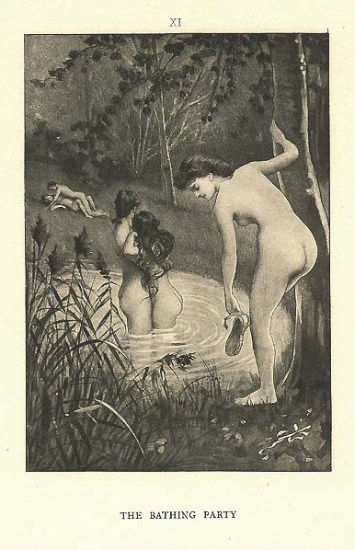

First, you’ve got the type of story epitomized by Moby Dick. Manly men doing manly things, almost entirely with each other. Guys lolling about under the covers together and comparing tattoos, or holding hands under the open sky as they wade through whale blubber. These are sweaty, hairy, deep-throated narratives; narratives red in tooth and claw; narratives of man vs. man, man vs. nature, and man vs. his own body odor; narratives where, in short, every chromosome that matters ends in Y.

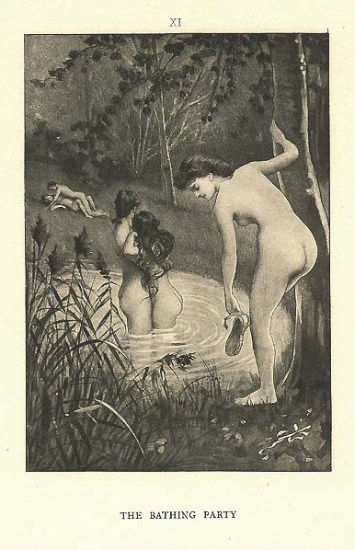

Second, you’ve got stories like Fanny Hill. In these tales, male characters are present, but secondary. What really matters is some vivacious, voluptuous, double X, into whose mysterious consciousness and orifices the reader and writer together raptly penetrate. Bloody conflict is replaced by fluid congress, silk sheets, perfume, lidded glances, and flesh in various degrees of drapery. The thrill is in knowing women from the inside out; in replacing, possessing, and becoming the object of desire.

I am excessively pleased with these categories, mostly because it allows me to label a wide array of cultural products as either Dick or Fanny. (The Old Man and the Sea — Dick! Breaking the Waves — Fanny! Go on, try it…it’s fun for the whole family!)

Where was I, anyway? Oh, right. In addition to the obvious adolescent satisfactions (Escape from New York — Dick!), I think the hermeneutic is also useful because it allows one to sidestep some of the more tired cultural arguments. For instance, the Dick/Fanny breakdown has little to do with quality or caché. Dick is epitomized equally by Herman Melville and James Bond (the latter of whom sleeps with women only as a strategy to get him closer to the villain, his real object of interest). Fanny, too, has high-brow permutations like Pedro Almodóvar or D.H. Lawrence, and lowbrow ones like Russ Meyer or Bella Loves Jenna.

By the same token, Dick/Fanny does not equate to sexist/feminist. Since Dick and Fanny are categories of male fiction, they both do tend to be sexist for the most part…though there are some exceptions (I think Jack Hill’s Pit Stop is an example of non-sexist Dick; his Swinging Cheerleaders is an example of non-sexist Fanny; you can see a fuller explanation here.) In any case, the point here is that Dick and Fanny don’t have a particular qualitative or moral value attached; one isn’t necessarily better or worse than the other.

Now that we’ve got that all, er, straight, let’s pick up our Dick and shift over our Fanny, and take a look at comics, since that’s supposed to be what we’re all here for.

American comics are, by and large, written primarily by men, for men. This is true of the mainstream super-hero books; it’s true of the classic underground titles, and it’s true to a somewhat lesser extent of the present-day alternative comics scene as well. (I’m going to ignore newspaper comic strips, which, at the moment, don’t really seem to be written for — or indeed, by — anyone.) So, since they mostly fit in our broad category of male narratives, which American comics can we classify as Fanny and which can we classify as Dick?

There are definitely some Fanny comics out there. Pretty much the entirety of porn qualifies, from Lost Girls to Housewives at Play. A fair bit of Crumb’s stuff is Fanny, as I’m sure he’d be pleased to hear. The Los Bros Hernandez books and Dan Clowes’ Ghost World are also obsessed with female bodies and/or psychology in a way that strongly suggests Fanny. There’s Catwoman, I guess. And then there’s….uh…maybe Chris Ware’s Building Stories? And also, um….

Not a heck of a lot, really. American comics are, as it turns out, not only overwhelmingly male-oriented, but also veritably awash in Dick. All those mainstream super-hero titles with muscle-bound good guy/bad guy pairs obsessing about each other; all those angst-ridden autobio drones whining about their isolated alienation from women, ….it’s all Dick, Dick, Dick all the time. Sure, there’s the occasional willing alterna-chic or preposterously attired superheroine to lend some T&A…but why are they so rarely the fetishized focus of the action? Kick-ass female-lead eye-candy has been a schlock staple in television and movies for the last decade. What’s comics’ problem?

Again, this isn’t necessarily to say that more Fanny would make comics objectively better. There are lots of good Dick cultural products, and bad Fanny can be quite, quite bad. But it does make you wonder. Lots of folks have pointed out that American comics don’t really reach out to women or girls or children — and they don’t, and they’re probably not going to, ever. But even if you accept that the core audience for American comics was, is, and most likely always will be increasingly paunchy guys, it still seems like the offerings are fairly limited.

Minx was doomed from the start, but surely, surely, if your main audience is men, you could produce an R-rated line devoted explicitly to sexploitation-style sleaze and get some of your regulars to buy it? You could even bring back some of the classic genres of 70s cinema; nurse comics, cheerleader comics, women-in-prison comics, rape-revenge comics. Call me a dreamer, but I know in my heart that my fellow comic readers would like Fanny just as much as Dick if they were only given the chance to try it.

__________

Illustration credits: Bill Sienkiewicz’s illustration from the Classics Illustrated Moby Dick; Paul Avril, Illustration for a 1908 edition of Fanny Hill