I wrote this when I was in college about 20 years ago. It’s probably a little earnest by my current standards, but what the hey; we were all young once.

________________________

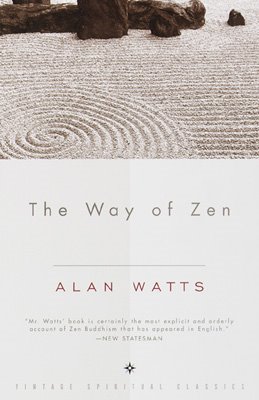

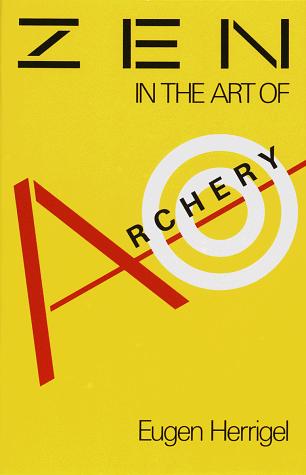

In The Way of Zen, Alan Watts points out that, in Japan, training in the arts “follows the same essential principles as training in Zen.” In this context, he specifically mentions Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery as “the best account of this training thus far available in a Western language.” (195) Herrigel’s narrative does, in fact, illustrate, in many ways, the Zen philosophies, or, perhaps more correctly, the Zen experience which Watts discusses. At the same time, however, the ideas which Herrigel derives from his studies differ noticeably, at several crucial points, from those which Watts cites as most characteristic of Zen. A comparison of the two accounts, then, can both provide insight into Zen Buddhism and illuminate the differing methodologies which Herrigel and Watts employ.

In The Way of Zen, Alan Watts points out that, in Japan, training in the arts “follows the same essential principles as training in Zen.” In this context, he specifically mentions Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery as “the best account of this training thus far available in a Western language.” (195) Herrigel’s narrative does, in fact, illustrate, in many ways, the Zen philosophies, or, perhaps more correctly, the Zen experience which Watts discusses. At the same time, however, the ideas which Herrigel derives from his studies differ noticeably, at several crucial points, from those which Watts cites as most characteristic of Zen. A comparison of the two accounts, then, can both provide insight into Zen Buddhism and illuminate the differing methodologies which Herrigel and Watts employ.

The most basic tenet of Zen, both Watts and Herrigel indicate, is that one should be unselfconscious; should have the ability to cease thinking. Watts explains that “the mind cannot act without giving up the impossible attempt to control itself beyond a certain point. It must let go of itself….” (139) Thus, as Herrigel puts it, one must become “purposeless on purpose.” (33) Herrigel’s training is, in large part, a technique for overcoming this basic contradiction. When Herrigel is practicing drawing his bow, his master exhorts him to “Concentrate entirely on your breathing,” so as to perform each action effortlessly, without thought. (21-22) As Watts points out, “breathing [is]…the process in which control and spontaneity…find their most obvious identity,” and so the concentration on breath is a means of destroying the illusion that it is necessary to think and plan in order to act.(197-8)

The purpose of Zen training, then, is to release the students own mental control over him or herself. This is often done, Watts suggests, through intensifying the student’s efforts at self-regimentation until the ultimate futility of this rigidity becomes so manifest that it spontaneously drops away. As the master demands that the student cease controlling himself, the student intensifies his efforts to cease intensifying his efforts, until, as Watts writes, he becomes “totally baffled by everything,” gives up utterly the effort to understand the world around him, and thus begins to act without thought.(166) This is precisely the process which Herrigel describes. “Weeks went by,” he writes, “without my advancing a step. At the same time I discovered that this did not disturb me in the least….I lived from one day to the next….” (52)

For both Watts and Herrigel, the final results of the achievement of self-liberation are, at the least, profound, and, at most, decidedly mystical. “When every last identification of the Self with some object or concept has ceased,” writes Watts, one enters “the state of consciousness which is called divine, the knowledge of Brahman….represented as the discovery that this world which seemed to be Many is in truth One….” (38) Herrigel, too, writes that when he finally shot without thinking, he discovered that “‘Bow, arrow, goal, and ego, all melt into one another, so that I can no longer separate them. And even the need to separate has gone.'” (61) Zen, therefore, is both a kind of psychological technique and a religion, both a means of promoting mental health and a way of discovering what Herrigel, especially, refers to as a deeper Truth.

Thus, Herrigel’s description of the experience of his training seems to follow and to demonstrate Watts’ outline of the essential precepts of Zen thought and teaching. However, there are several difficulties in reconciling the two accounts, partially centering around the fact that, for Watts, Zen’s emphasis on spontaneity and its essentially anti-institutional character makes any effort to teach Zen problematic. (169) The central point of Zen, Watts contends, “is that in fact we are already in nirvana — so that to seek nirvana is the folly of looking for what one has never lost.” (61) This means, of course, that the attempt to “learn” Zen is, at base, misguided, and that, therefore, Herrigel’s quest is itself a refutation of the object that he seeks.

Supposedly, therefore, when Herrigel “awakens” he should recognize the futility of his search — and this recognition should be apparent throughout his book, since he wrote it, after all, following the completion of his training. This is not, however, the case. Instead, Herrigel repeatedly refers to his studies as purposeful, progressing clearly through stages. “…the breathing,” he writes, “had not of course been practiced for its own sake,” while the Master himself remarks after his class has successfully drawn their bows that “‘All that you have learned hitherto…was only a preparation for loosing the shot.'” (20-27) Towards the end of the training the Master even explicitly suggests that his students are headed for a specific destination, commenting that “‘He who has a hundred miles to walk should reckon ninety as half the journey…'” (54) Watts, on the other hand, insists that “Zen…is a traveling without point….To travel is to be alive, but to get somewhere is to be dead….”(197)

Related to Watts’ emphasis on the futility of searching for Zen is his insistence on the manner in which Taoism, and later Zen, “made Buddhism a possible way of life for human beings….” (29) Watts points out that since everyone is already in a state of awakening, Zen has “no need to…drag in religion or spirituality as something over and above life itself.” (152) To separate the Zen experience from normal everyday life, to create a special “spiritual” realm, is, in fact, diametrically opposed to the very basis of Zen, which recognizes that “‘all duality is falsely imagined.'” (38) Thus, just as to search for Zen is to conceal that for which one searches, to confine Zen to one portion of one’s life, to suggest that Zen inhabits a realm to the side of the world in which one eats and sleeps, is to eliminate that which one attempts to confine. This is why when the holy man Fa-yung achieved awakening, the birds no longer brought him flowers, for upon being awakened, he cast off his holiness, and became simply human. (Watts 89-90)

For Herrigel, however, the art of archery, and Zen itself, is a mystical experience, distinctly separate from, and distinctly beautiful in comparison to, the incidents of “normal” life. Before he began his undertaking of archery, he writes, he “had realized…that there is and can be no other way to mysticism than the way of personal experience and suffering.” (14) Each of the Zen arts, he insists, “presuppose a spiritual attitude…an attitude which, in its most exalted form, is characteristic of Buddhism and determines the nature of the priestly type of man.” (6) The study of archery, in fact, separates Herrigel from the rest of the world, for his Master informs him that “when you meet your friends and acquaintances again in your own country:things will no longer harmonize as before. You will…measure with other measures.” (65) [1] Similarly, when the Master “gave a few shots with [Herrigel’s] bow, it was as if the bow let itself be drawn…more willingly.” (59-60)

For Herrigel, then, Zen is, seemingly, primarily a religious experience, while Watts is more interested in understanding the philosophical and psychological implications of Zen thought. Where Herrigel, for instance, discusses the deep feeling of gratitude which the pupil feels for his teacher, Watts investigates the manner in which Zen uses the master as authority figure in order to create a “formidable archetype” from which the student must free himself. (Herrigel 46, Watts 163) Thus Herrigel is more concerned with the emotive quality of the relationship, while Watts concentrates on the purpose of the master-pupil contact, and on its effectiveness in provoking “awakening”.

Watts, in other words, is far more objective, and in many ways, therefore, a good deal more convincing in his description of Zen than is Herrigel. It is difficult to take Herrigel too seriously when he makes such statements as “[The student] must dare to leap into the Origin, so as to live by the Truth and in the Truth….” if only because any mention of “Truth” immediately provokes a large swell of skepticism, at least in the Western student. (81) Watts, on the other hand, takes care to set forth his own limitations, and to point out the difficulties of discussing a subject which is so vividly linked to experience. (xii) As a result, one almost automatically begins to judge Herrigel’s work by the standards which Watts constructs.

Yet Zen is, as Watts himself points out, a philosophy which is vehemently opposed to the use of the “critical perspective.” (xiii) If the central tenet of Zen is an opposition to overthinking, then evaluating that tradition itself is, obviously, self-contradictory. Watts’ argument that “basic reality, remains spontaneous and ungrasped whether one tries to grasp it or not” is intellectually satisfying, and in itself, powerfully liberating. But it is difficult, on the basis of such largely theoretical statements, to deny the validity of Herrigel’s first-hand experience, especially given Zen’s emphasis on action over thought. Ultimately, perhaps, Watts says all that can be said about the Zen tradition, while Herrigel tries, in a manner which may be misguided (though that too, is somewhat difficult to judge) to illuminate portions of that experience which might better be left undiscussed, since verbalizing them seems, at least for Herrigel, to lead to a kind of generalized and unconvincing mysticism. Nonetheless, to refute the role of Zen in archery because of the limitations of Herrigel’s narrative would be a disservice to Herrigel, to Zen itself, and to Watts, whose brilliant discussion of Zen nonetheless takes pains to remind his readers of the limitations of words in describing and explaining a system which is, at heart, more an experience than a philosophy.

[1]Besides contradicting Watts, this statement is also particularly confusing, since, after all, it seems relatively obvious that, with or without Zen, after spending five or six years in Japan, Herrigel would virtually have to expect that his relationships with his friends and acquaintances would be somewhat changed.