I just finished DC’s Wonder Woman Chronicles volume 1, which collects Wonder Woman’s appearances in chronological order. This first volume collects Wonder Woman’s first appearance in All-Star Comics 8 (December 1941-January 1942) through Sensation Comics no. 9 in September 1942, and also includes Wonder Woman number 1.

I’ve already talked about several of these comics in the Bound to Blog series (for example, I talk about Wonder Woman #1 here, and Sensation Comics #1 here.) But there are a couple of things that struck me while reading the collection as a whole.

No Intro

There’s absolutely no introductory material at all, unless you count a small note in the table of contents that says, “The comics reprinted in this volume were produced in a time when racism played a larger role in society and popular culture, both consciously and unconsciously.” That is undeniably true

but still, it seems like there might be more to say. Who wrote these comics? Who drew them? How popular were they? What did people think of them? Why are we reprinting them?

Of course, the answer to the last question is basically, “because they are there,” and also, “Wonder Woman still has a fanbase, so if you stick her face on a cover, you can sell some copies, even if no one really thinks this material is particularly worthwhile — or, for that matter, thinks anything about it at all.”

Not that this is just about Wonder Woman. I’m sure DC’s other chronicles editions don’t have intros…the point is to make them as cheap as possible, I’m sure, in the hopes of selling to a not-especially-well-defined audience of WW fans, kids, and the curious or confused. But even the DC Wonder Woman Archive Edition (hard backed, more expensive, slightly more material) has an intro (by folk singer Judy Collins) that is more along the lines of an extended blurb than an actual effort to provide some context.

I’m sure some might say this is for the best — why have some professor get between the kids and their pop culture ephemera? The problem is that pop cultural ephemera is ephemera; if that’s what it is, why reprint it? And, indeed, DC’s various archival projects have tended to founder from lack of interest, being released at glacial speeds before instantly going out of print. Those boring professors, it turns out, are part of minimal cultural validation — and without that minimal validation, old pop cultural ephemera is largely irrelevant.

Steve Trevor, He-Man Convalescent

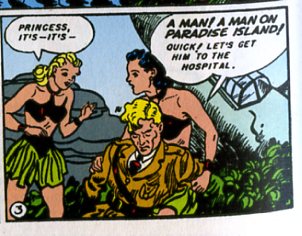

Steve Trevor appears on the very first page of Wonder Woman’s first story in All Star comics. In that debut appearance, he’s unconscious.

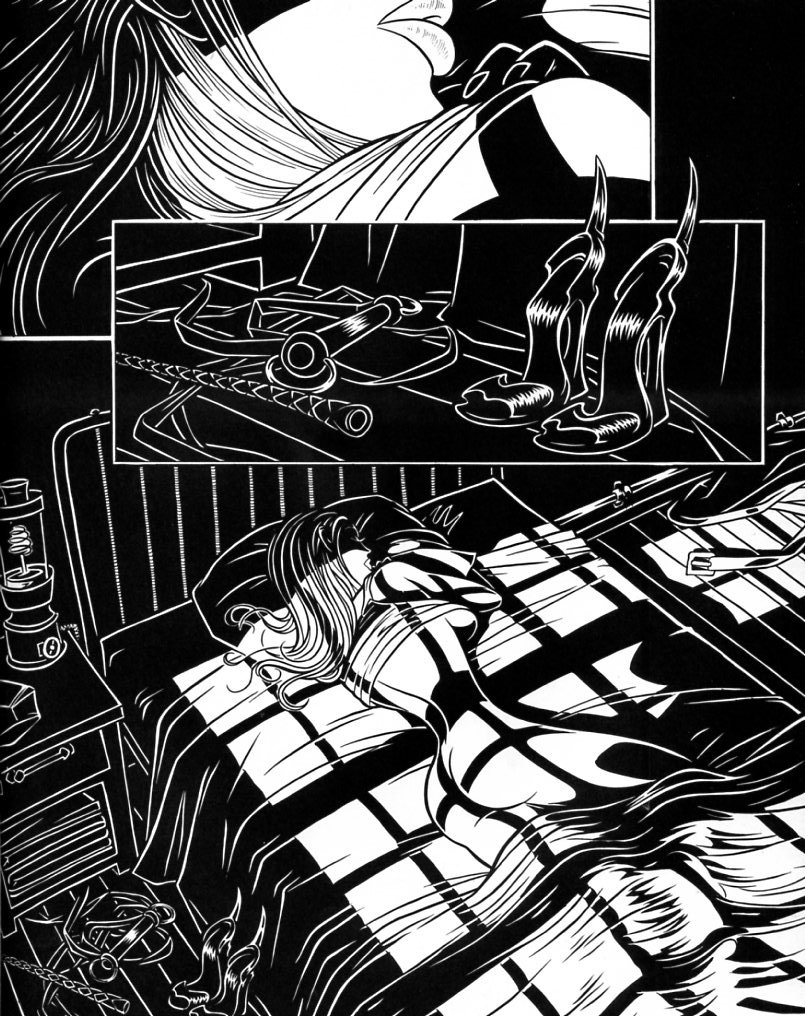

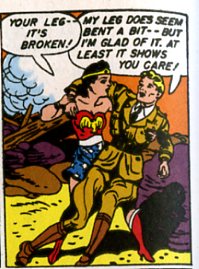

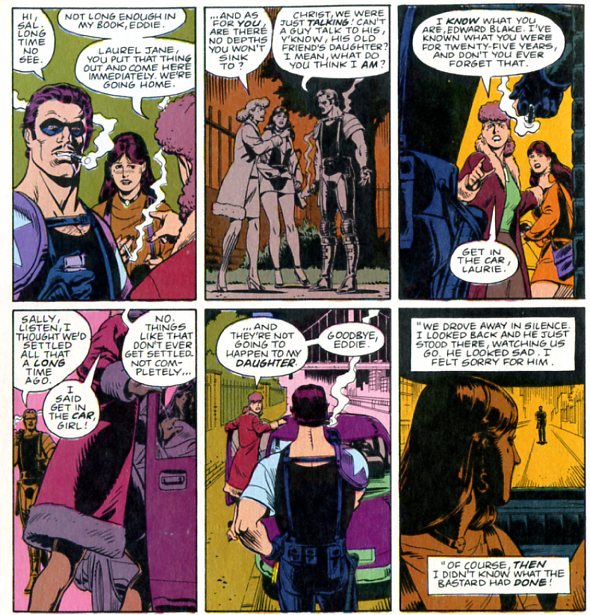

He then stays unconsious throughout the entire tale. He gets some moments of lucidity in flashback, but by the end of the story, he’s still conked out. It’s only in the 2nd WW tale (in Sensation Comics #1) that he comes to his senses. After that he’s in the hospital convalescing. He sneaks out when he learns of deadly danger to the country…but by the end of the comic, he’s back in bed again, with WW as Diana Prince (who changed places with his nurse…don’t ask) caring for him. Next issue he’s up and around, but by the end:

It’s only in Sensation Comics 3, the fourth WW story, that Steve Trevor escapes from the hospital, forcing Diana Prince to get a job not as his secretary, but as his boss’ secretary.

In other words, the ur-Steve Trevor, as Marston conceived of him, is not a fighter nor a love, but a hospital patient. The true Steve Trevor is the wounded — or, perhaps more accurately, infantilized — Steve Trevor.

In Women’s Fiction of the Second World War: Gender, Power, and Reistance, Gill Plain argues that:

War creates a situation in which the gender debate is subsumed by a meta-narrative of power. It represents a conflict that divorces and prioritises the division between activity and passivity from the founding binary opposition masculine/feminine. War almost represents itself as a constructive reinscription, or even a rejection of the age-old formulations of gender…. In the course of purusing the division between a non-gender-specific activity and passivity, woman is ‘decentered’… The woman has once again become invisible.

For Plain, then, war destabilizes gender by divorcing activity/passivity from gender — but in so doing, it erases women’s difference, and so erases women.

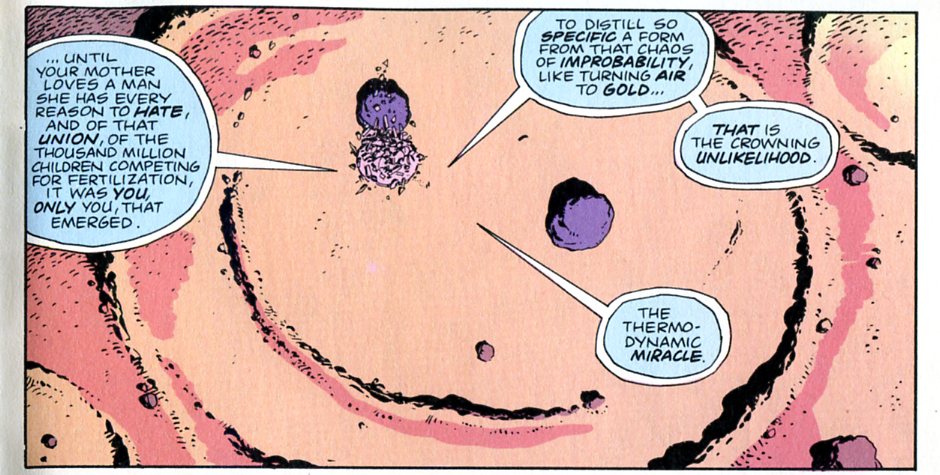

I think, though, Marston, radical feminist and dirty old coot, has found a way around this dilemma. He uses the destabilizing effect of war to create an emasculated hero — the wounded soldier, whose incapacity is the sign of his boldness and strength. But for Marston, the fact that passivity is disconnected from women does not result in ungendering. On the contrary, it becomes a masochistic fetish. Steve regresses, authority is upended…and patriarchy becomes matriarchy. Woman isn’t erased; she’s explicitly elevated as caregiver and (maternal) hero. Which is (in Marston) what men want:

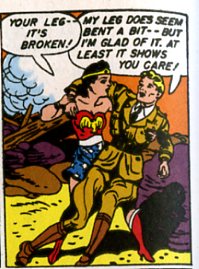

That’s an awesomely, fluidly flaccid twisted leg Peter has drawn there — and Steve is, of course, explicitly getting off on his own castration. War for Marston isn’t a disaster so much as an opportunity for men to embrace their weakness…and let women take over.

Myself for a Rival

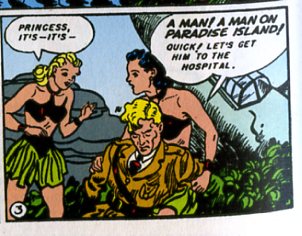

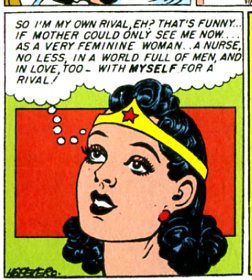

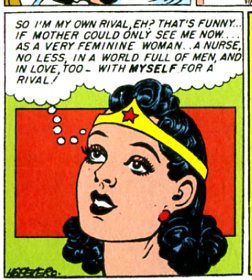

A number of the stories in this volume end with a panel like this

What’s interesting about this is that…that’s it. The trope is stated…and then dropped, over and over again. The love triangle is pointed at, but never really becomes central to the plot (the way it is with the Clark/Lois/Superman triangle, even in the early years to some extent.)

It seems like, for Marston, there’s a pleasure in the masquerade of changing identities, and a frisson in the unrequited melodrama…but very little interest in actually presenting either Diana or Wonder Woman as angst-ridden or, for that matter, weak. There’s almost a condescension about it, like she’s pretending she’s worried to make Stevie feel important, the little darling. As I’ve mentioned before, double identities in Wonder Woman feel more like play than agonized bifurcation, a polymorphous feminine role-play rather than an agonized Oedipal bifurcation. After Marston died, of course, Diana’s love vicissitudes move from marginal tease to major plot points. With Marston’s feminism removed, everybody seemed more comfortable with a passive object of desire, rather than with the all-powerful Mommy, stooping to love.