I’ve recently finished reading Ben Saunders’ book, Do the Gods Wear Capes?: Spirituality, Fantasy, and Superheroes. It’s a really enjoyable study. The chapter on the Marston/Peter run on Wonder Woman in particular filled me with bitter envy; I wish I had written it, or that if I had it would have been done so thoughtfully.

I’ve recently finished reading Ben Saunders’ book, Do the Gods Wear Capes?: Spirituality, Fantasy, and Superheroes. It’s a really enjoyable study. The chapter on the Marston/Peter run on Wonder Woman in particular filled me with bitter envy; I wish I had written it, or that if I had it would have been done so thoughtfully.

Anyway, perhaps in recompense for my blighted hopes, I thought I’d talk a little about the non Marston-Peter parts of the book and about some differences I have with it. In doing so, I’m going to refer to Ben as “Ben”, because we’ve been corresponding, and so it feels weird to call him by his last name. Hopefully he won’t resent this or other liberties.

So as the title of the book implies Do the Gods Wear Capes? looks at superheroes in terms of religion. However, Ben is not (thank God) adding to the dreary discourse which attempts to validate superheroes by asserting that they are modern myths. Rather, he makes the much more interesting claim that superheroes are myths about modernity. To quote his conclusion at some length:

Superheroes do not render sacred concepts in secular terms for a skeptical modern audience, as is sometimes claimed. They do something more interesting; they deconstruct the oppositions between sacred and secular, religion and science, god and man, the infinite and the finite, by means of an impossible synthesis. They are therefore fantasy solutions to some of the central dichotomies of modernity itself. A cynic might conclude that the suspension of disbelief required to enjoy such fantasies applies no less to their unlikely depictions of ethical perfection as it does to the spectacle of men and women who can fly, climb walls, and see through satellites. But, less cynically, we might instead interpret these stories as testaments to the strength of not just our will-to-power, but also of our will-to-love — our will-to-kindness, concern and decency. The dream of the superhero is not just a dream of flying, not just a dream about men and women who wield the powers of the gods. It’s also a dream about men and women who never give up the struggle to be good. W.B. Yeats once wrote, “in dreams begin responsibilities.” But perhaps possibilities of all kinds begin in dreams. And perhaps among these possibilities there is still the prospect of a spiritual awakening — even from within the skeptical, rationalist, materialist assumptions of modernity.

Ben works this theory through in terms of a number of characters…but he starts, logically enough, with Superman. For Ben, Superman isn’t defined as the quintessence of strength or the quintessence of power — rather he’s defined by “essential goodness”. Various creators have attempted to struggle with what “essential goodness” means in various ways. Ben talks about the early Siegel/Schuster issues, in which Superman beat up capitalists, suggesting an uneasy antagonism between the good and the democratic/capitalist institutions of the United States. In the 1950s, Ben says, Superman comics linked “the good” and the United States in a more straightforward manner (“Turth, Justice, and the American Way!”) Later, in the 70s and 80s, creators who worked on Superman struggled with his establishment image. For instance, Ben points to the Eliot S! Maggin story “Must There Be a Superman?” in which Superman is told by the Guardians of the Universe that his presence on earth is hurting the moral development of humanity, and in which he is confronted with the moral dilemma of how, or whether, to encourage migrant farm workers to organize.

People often argue that superheroes are dumb because they’re simplistic; because they create a bone-headed binary between good and evil. Ben’s argument is that, in fact, Superman stories have traditionally not so much asserted as investigated this binary. In the light of late modernity, as religion has faded, Superman asks “how can human beings be good?”

Ben finds one of the most effective answers in the Morrison/Quiteley All-Star Superman, in which Superman-as-reporter=Clark-Kent visits Lex Luthor in prison. Luthor spends the entire visit boasting about his greatness and threatening Superman and so forth. Unbeknownst to Luthor, though, riots and chaos are breaking out in the prison around him, and Superman-as-Clark has to save his life repeatedly. Ben concludes:

At such poignant moments, we see that only Luthor’s vanity could allow him to think of Superman as his enemy. In fact, Superman is his gentle savior — so gentle that even as he preserves Luthor’s life, Superman allows him to maintain his illusions of power and control. Thus, through Luthor, we see that Superman’s devotion to humanity is such that even the worst of us will always be treated with infinite patience and compassion. The results are both funny and moving, and leave the reader in no doubt as to the most incredible aspect of Superman’s character. Few human beings are ever so good. This, perhaps, is the final, paradoxical lesson that we can draw from the 70 years and more of Superman’s adventures — that it may be easier to fly, to see through walls, and to outrace a speeding bullet, than it is to love your enemy.

The sentence that most stays with me from that paragraph is this: “Few human beings are ever so good.” I like it’s simple wistfulness, and I like the way it suggests that, while few are, some might be — that goodness is, after all, something we can share with Superman. Being good isn’t a fantasy. It’s something people can strive for.

But while I like that sentiment, I also feel it’s perhaps a little misleading. Because while human beings can be good, they can’t actually be good in the way that Superman is being good in Ben’s description. The goodness Superman offers, in Ben’s telling, is the goodness of providing complete physical protection while simultaneously allowing the object of that protection to not know what is happening. Obviously there’s a metaphorical sense in which this could happen — anonymous charity, for example. But, in the first place, we’re not reading about anonymous charitable donations, and part of the reason we’re not reading about anonymous charitable donations is, surely, because we would rather watch Superman exercise his many, many superabilities. And, in the second place, even the “anonymous charity” analogy is a vision of the good dependent on a disproportion of power.

Ben is attempting to disaggregate. He looks for the most essential superquality, and that quality is goodness. All the others — strength, speed, flight, superbreath, and on and on — are just gilding on the basic concept. Superman is not about the powers. He’s about the good.

But what if, instead, he’s about both? Or what if, even, the good is essentially one of his powers? Tom Crippen suggests something like this in his own take on Superman and modernity.

Superman has a fine temperament and a lovely smile. It’s not a question of him personally being cold. I saw him on the cover of a kids’ book of math problems, or possibly it was a display ad for an insurance company. But he was taking off into the air and looking delighted about it, and why not? The reaction was perfectly right for him. He’s agreeable and fun loving; that’s not the whole of his personality, but the stuff is in there. It’s there along with all the other qualities the best sort of personality would have. You can assume the presence of all of them, whatever they are; they’re implied, and any of them can surface. If Superman flies off looking keen and determined, that suits him too. So the problem isn’t so much that Superman himself is pompous, either in his icon form or as a continuing-story character. It’s that, as a character, he seems like an afterthought to himself. Everything about him is derived in such a straight line from the central premise—this man is super—that there’s not much point to experiencing him.

Tom sums up the point by saying that Superman, “By definition, by being super, he is the best of whatever comparison he finds himself in. If he is one of two large men, he is the best—that is, strongest—of the two of them.”

By the same token, there are two good people in a room, Superman is the most good.

And part of the reason he is the most good, I think, is because he is also the most strong. The goodness of Superman can’t be disaggregated from the superness; the two are intertwined, and that intertwining has meaning. If the ultimate good is the ultimate force, then it seems logical to conclude that goodness and force rely upon each other.

Here’s another take on force and heroism from Simone Weill’s The Iliad, Or The Poem of Force.

Force, in the hands of another, exercises over the soul the same tyranny that extreme hunger does, for it possesses, and in perpetuo, the power of life and death. Its rule, moreover, is as cold and hard as the rule of inert matter. The man who knows himself weaker than another is more alone in the heart of a city than a man lost in a desert…

Force is as pitiless to the man who possesses it, or thinks he does, as it is to its victims; the second it crushes, the first it intoxicates. The truth is, nobody really possesses it. The human race is not divided up, in the Iliad, into conquered persons, slaves, suppliants, on the one hand, and conquerors and chiefs on the other. In this poem there is not a single man who does not at one time or another have to bow his neck to force.

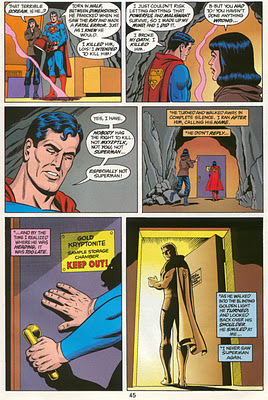

There is one Superman tale I can think of that captures some of Weill’s insight into force. That would be Alan Moore and Curt Swan’s “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” In this “imaginary” story, Superman deliberately kills an overpowering enemy..and then, in expiation, exposes himself to gold kryptonite, destroying his powers. Here, force and goodness are definitively separated; the first, as Weill suggests, must be cast off if the second is to survive. But when force disappears, so does Superman. What’s left is a good man who is not a superhero — a good man who decisively declares “Superman was overrated. Too wrapped up in himself. Thought the world couldn’t get along without him.” At that point, the comic ends. Superman is still supergood, but he can no longer perform superfeats…and the superfeats were, as it turns out, the point.

I think Ben would respond to this by saying that superhero comics have confronted these very issues — that they explicitly question the goodness of power. Ben talks about this most directly in his last chapter, which focuses on Iron Man (aka Tony Stark). Ben notes that from his inception, Iron Man expressed

ambivalence towards technology — desired as a source of power, but feared and resented, as the cause of a crippling dependency for those who rely upon it…. [This is a] fundamental element of the original version of the Iron Man character — built into his armor, we might say, in the form of his chest plate, which is not only the main energy source for the suit, but also prevents the inoperable fragments of shrapnel embedded in his chest during his days in Vietnam from reaching his heart and killing him. Tony Stark’s very life depends on this piece of equipment; consequently, he can never remove it, amking it a resonant symbol of the double-edged nature of his techno-dependence, as well as a literal barrier to intimacy.

Ben argues that this ambivalence about technology — ultimately an ambivalence about power and humanity’s wielding of power — cryztallized in a 1979 storyline by David Michelinie, Bob Layton, and John Romita, Jr. known as Demon in a Bottle. The story centered on Stark’s effort to get out of the armaments industry, and the government’s subsequent plot to take over control of his company. In addition, the arc follows Tony’s struggles with alcoholism. In the story, Ben argues, dependence on alcohol and dependence on technology are linked. Both alcohol and the Iron Man suit are technologies of control; alcohol providing the illusion of control over one’s own emotional state, the suit providing the illusion of control over….well, everything else.

The cure for both forms of dependency, it turns out, is to acknowledge that the fantasies of radical independence — absolute power, total control, complete self-reliance — are just that: fantasies. The answer to the problem of negative dependence is therefore not the pursuit of independence…but the radical acceptance of interdependence.

In a virtuoso move, Ben then links this realization to the ideology of Alcoholics Anonymous — an ideology which Ben argues is specifically focused on modernity’s obsession with control and power. Leslie Farber, a psychoanalyst whose theories were central to AA, is quoted by Ben as follows:

“Nietzsche, I believe, was not as interested in theological arguments about the disappearance of the divine will in our lives as he was in the consequences of its disappearance. Today the evidence is in. Out of disbelief we have impudently assumed that all of life is subject to our will. And the disasters that have come from willing what cannot be willed have not at all brought us to some modesty about our presumptions.

For AA, of course, the solution to this solipsistic mania for control is to put one’s faith in a nondenominational higher power — to acknowledge that one does not have the ultimate power over one’s own life, much less over the world. Ben links this realization to a Warren Ellis/Adi Granov Iron Man story from 2005, in which Stark experiences something like a crisis of faith, and is able to go on only by acknowledging the limits of his own power and knowledge. Stark in this story does not know that he is doing the right thing…but his uncertainty is itself the (ambivalent, uncertain, but still) sign of his goodness. Like a recovering alcoholic (which Stark is), the acknowledgment of his own limits allows him to function, and to function for good.

The problem, though, is precisely with the “function”. AA critiques alcohol as a technology of (false) control. But the solution it offers is a solution — which is to say, it is a technology itself. The 12-step program is a program, a system, a utilitarian fix. It specifically brackets content (what exactly is that higher power?) in the interest of getting the alcoholic back to becoming a functional member of society. As Ben says, AA does not insist on the existence of God, but rather “insists on the necessity of the God concept.” God is not a transcendent hope; he’s a convenient tool, like a socket wrench.

Tony Stark does not, then, take off his suit of armor to find vulnerability and connection; he takes off his suit of armor to put on a bigger, badder, better suit of armor. The acknowledgment of his dependence and powerlessness is not the beginning of a different kind of story. Tony Stark does not change his life; he is still committed to an existence where he gets up, suits up, and shoots bad guys in the face with repulsor rays. The change for Stark is simply a retooling; humility is a necessary pit stop on the way to greater feats of godlike power. The means, in this case, justify the end. AA is a part of, not a solution to, the technological pragmatism of modernity, in which even god is valued solely as a cog in an ever-more-functional machine.

That’s the case for superhero comics as well, I think. Ben is right when he sees superheroes as a myth of modernity. But I think he’s overly-optimistic when he sees in that myth a hopeful sign of a possible spiritual reawakening. Rather, it seems to me that superhero comics suggest not modernity’s possible salvation, but its depressing limits. For both superheroes and modernity are genres in which the good waits upon the powerful.