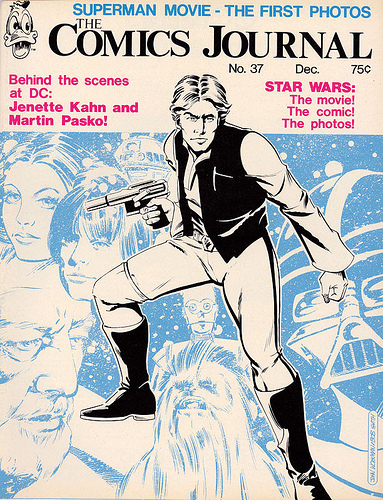

A couple of days ago, my twitter feed displayed the following message from TCJ.com.

Today we worship the latest by @xaimeh with pieces by Dan Nadel http://bit.ly/oZjPF2, Frank Santoro and Adrian Tomine http://bit.ly/mV9U8W

I’ve liked things that both Dan and Frank have written in the past — Dan’s piece on the Masterpieces of American Comics exhibit was probably my favorite selection in the Best American Comics Criticism volume that Fanta published a year or so back. And tcj.com has been doing a lot of good things since they sent us packing (this lovely piece by Craig Fischer, for instance. So I was assuming that that “worship” was just a bit of jocular hyperbole. Obviously the pieces would be laudatory, but I had hopes they wouldn’t be sycophantic.

Alas, if you click the link you get what the tweet says; Jaime’s comics transubstantiated into communion wafers, less to be read and discussed than to be consumed as a path towards union with the divine. Thus, Frank expresses awe, reverence, and wonder, talks about breaking down into tears, lauds the purity and uniqueness of Jaime’s talent, and finishes up with what reads like literal hagiography.

No art moves me the way the work of Jaime Hernandez moves me. I am in awe of his eternal mystery.

Tomine’s piece is more of the same, albeit shorter. In comments, Jeet Heer suggests that it might be worthwhile to compare Jaime’s work to Dave Sim’s. This does seem like an interesting juxtaposition, but Frank nixes it insisting, “Lets be careful to not make this thread about Sim. This is a Jaime celebration.” No criticism at TCJ, please. Only celebration, worship, and gush.

To be fair, neither Frank nor Tomine are making any pretense of trying to explicate, or really even engage, with Jaime’s work. Instead, both of their pieces are testimonials — personal accounts of having seen the light. From Frank’s piece

Something extraordinary happened when I read his stories in the new issue of Love and Rockets: New Stories no. 4. What happened was that I recalled the memory of reading “Death of Speedy” – when it was first published in 1988 – when I read the new issue now in 2011. Jaime directly references the story (with only two panels) in a beautiful two page spread in the new issue. So what happened was twenty three years of my own life folded together into one moment. Twenty three years in the life of Maggie and Ray folded together. The memory loop short circuited me. I put the book down and wept.

We don’t need to see the two panels in question reproduced (or, indeed, any artwork from the story reproduced), because it’s not about the panels. It’s about the effect of those panels, and of Jaime, in Frank’s life. Jaime is transformative because Frank says he’s been transformed. It’s a witness to true belief by a true believer for other true believers. The imagery of short circuits and closed loops is unintentionally apropos.

Dan’s essay is nominally a more balanced critical assessment. In practice, though, it’s got the same religion minus the passion, resulting in an odd combination of towering praise coupled with bland encomium. Frank’s piece has the energy of an exhortation; Dan’s, on the other hand, reads like a painfully distended back-cover blurb. “The Love Bunglers”, Dan declares, is the story of Maggie “finally holding onto something.” Jaime’s art is great because it is personal, so that “this alleyway is not just any alleyway — it’s an alleyway constructed entirely from Jaime’s lines, gestures, and pictorial vocabulary.” And the big finish:

In the end we flash forward some unspecified amount of years: Ray survives and he and Maggie are in love and Jaime signs the last panel with a heart. “TLB” is also a love letter from its creator to his readers and to his characters. It’s a letter from an old friend, wise to the fuckery of life, to the random acts that occur and that we have no control over. Jaime, I think, used to be a bit of a romantic. He’s not anymore, but in this story he gives us something to hang onto: A piece of art that says that you should allow fear and sadness into your life, but not let those things cripple you. That sometimes life works out and sometimes not, but the things we can control, things like comics and storytelling, carry redemption.”

Let fear and sadness into your life but don’t let them cripple you. Sometimes life works out and sometimes not. It’s criticism by fortune cookie. And…signing the last panel with a heart to show us the power of love? Gag me.

The point isn’t that “Love Bunglers” isn’t great. I haven’t read it; I don’t have any opinion on whether it’s great or not. But I wish instead of telling us that this is one of the greatest comics in the world no really it is, Dan would have taken the time to develop an actual thesis of some sort — a reading of the comic that elucidated, unraveled, and interracted with its greatness, rather than just declaiming it.

I’m talking here specifically as someone who is interested in and conflicted about Jaime’s work. I would like Dan, or someone, to write something that would allow me to see why this particular sentimental melodrama dispensing life wisdom is better than all the other sentimental melodramas in the world that are also dispensing life wisdom. But instead all Dan provides is assertion (“It just works. They’re real.”), predictable appeals to vague essentialism (“There are no outs in his work — what he lays down is what it is.”) and paeans to nostalgic retrospection (“As I took it in, I realized that I remembered not just the moments Jaime was referring to, but also the narratives around those moments. And furthermore, I remembered where and how and what I was when I read those moments. I remembered like the characters remembered.”) If I am unconvinced by standard-issue authenticity claims and do not have years and years of reading Jaime comics to feel nostalgic about, what exactly does “The Love Bunglers” have to offer me?

Part of the trouble here may be that it’s difficult to write about something you like as much as Dan likes Jaime’s work. Love can sometimes reduce you to gibbering — which is understandable, though not a whole lot of fun to read for someone who isn’t under the influence of similar giddiness. I think it can also be especially tricky to write about soap-operas, where a large part of the point is personal emotional attachment to individual characters. If the narrative deliberately figures the reader as fan or lover; it can be hard to say anything other than, “I adore this character! I adore this author! I’m in love I’m in love I’m in love! It’s so awesome!”

I don’t have a problem with people writing to say that something they love is awesome. I’ve been known to do it myself even. But this is TCJ,…and it’s Jaime Hernandez — the most prestigious publication devoted to comics criticism focusing on one of the most lauded contemporary cartoonists. If they wanted to run one love letter, I guess I could see it…but two or three? Surely, nobody in TCJ’s audience needs to be told that Jaime is awesome. Everyone knows Jaime is awesome. Except, possibly, for a few weirdos like me who are waiting to be convinced. But if this is the case, why forego actual nuanced and possibly convincing discussion of his work in favor of vacuous cheering?

Partially no doubt it’s because comics remains permanently tucked in a defensive crouch. No matter how unanimous the praise of Jaime is, no matter how firmly he is canonized it will never be sufficient to undo the brutal unfairness of the fact that he’s not as popular as…Frank Miller? Harry Potter? Andy Warhol? Lady Gaga? Somebody, in any case, can always be trotted out to show that the really famous and canonical person you love is not famous and canonical enough.

But there’s also a sense in which TCJ’s tweeted fealty is less about Jaime (who surely doesn’t need the flattery) and more about the celebration of fealty itself. You worship at the altar of Jaime because worshiping at the altar of Jaime is what the initiated do. The sacramental praise both constitutes an identity and confirms it for others. You are in the club and enjoying the hobby in the proscribed fashion. Fellow travelers shall take you to their bosoms, and even the chief muckety-muck shall weigh in with a heartfelt and avuncular hosannah.

Comics was long a subculture first and a subculture second and an art a distant third. TCJ set itself to change that. Certainly, it has altered the list of holy objects. But the rituals remain depressingly familiar.

____________

Update by Noah: This is part of an impromptu roundtable on Jaime and his critics.