I have been reading a lot about Wonder Woman recently. Actually, I have been reading a lot about Darna recently, but it is very difficult to theorise Darna without turning to theories about Wonder Woman because, as readers of this blog are no doubt aware, the Wonder Woman comics can often seem to be to the study of superhero comics as gravity is to physics; they were there (almost) from the beginning of the genre, they have been at the center of many important debates, and, despite being the subject of work by some of our best minds, one has the sense that we have barely scratched the surface of all there is to be said about them.

I would like to center this discussion on an incarnation of Wonder Woman who exists only in a single image (discussed in two separate posts), created by one Aaron Diaz, proprietor of the webcomic Dresden Codak and blog Indistinguishable from Magic. This incarnation of Wonder Woman is noteworthy, I believe, because Diaz is highly engaged in issues of gender representation in popular culture and one finds in his work a palpable feminist agenda (I should probably add, in the interest of full disclosure, that I am a long-time fan and supporter of Diaz’s work). While, in my argument below, I read Diaz’s work as a compelling intervention, I nonetheless believe that his Wonder Woman creates problems with regard to gender even as she solves others, thereby opening up interesting questions with regard to female superherodom.

Diaz’s Wonder Woman was created in direct response to DC’s New 52, but also provided an opportunity for him to address some long-standing characters who he finds to have historically suffered from poor design. He chose Wonder Woman on the grounds that ‘[a]lthough a feminist pop icon, her origins are too tied up with creator William Marston’s obsession with bondage. Because of this (and an all-too-frequent parade of poor or sexist writing), she’s never had a solid, progressive design.’ As other contributors to this blog have shown, the (to put it mildly) recurring bondage theme Marston’s Wonder Woman comics need not be read as anti-feminist. Diaz is not entirely incorrect, however; as many have argued, Wonder Woman’s apparent status as em(super)powered woman and feminist icon has historically been undercut by images of her as erotic spectacle (these links are work safe this one is not). One may not agree with his dismissal of the Marston/Peter run, but can at least understand his desire to reinvent Wonder Woman in light of the New 52 and other incarnations.

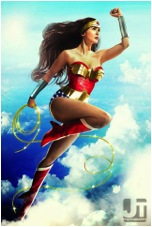

Diaz does not dispose of Wonder Woman’s swimsuit, but covers it with a ‘more conservative’ mid-thigh Greek-style dress, thereby moving away from the overtly sexualised Wonder Women. Diaz’s Wonder Woman is, in accordance with her origin story, made from clay. Where, in other incarnations of the character, this statue then became flesh, Diaz’s Wonder Woman remains a ‘statue come to life.’ Diaz thus draws a link between sculpture and superhero comics as two mediums which have historically fixated on bodily perfection. Because she is made from hardened clay, Diaz’s Wonder Woman resonates with the ‘metalisation’ of the male body one encounters in films during the 1980s when, in light of the AIDS crisis, cinema sought to enforce masculine bodily boundaries. This tradition certainly continues in superhero comics today, where characters such as Colossus play out the fantasy of impenetrable metallic bodies.

Diaz also replaces Wonder Woman’s lasso with a sword ‘that contains the lightning of Zeus.’ Given that Wonder Woman’s lasso is, as Berlatsky contends, ‘a vagina as surely as James Bond’s gun is a phallus’, Diaz thus symbolically makes Wonder Woman a man or, at least, equips her with the idealised hyper-male attributes of an impenetrable body and impressive phallus. The powers of her lasso are transferred to a shield ‘containing the wisdom of Athena (which, when using its reflection, can reveal a person’s inner self and compel them to tell the truth)’. Where the lasso contains her enemies, the shield repels them, further enforcing the impenetrability of Wonder Woman’s metallised body.

Clearly, Diaz’s work is motivated by a strong feminist agenda. His Wonder Woman is deliberately drawn against the eroticisation of the female superbody. She also continues the appropriation of (super)male attributes begun in her inception; she not only possesses the strength and invulnerability of Superman, but has been given the hardened body and phallus traditionally reserved for other male superheroes. One might ask, however, if the accruing of (super)male signifiers is truly a step-forward, or if it requires the evacuation of that which makes Wonder Woman such a powerful feminist icon? One might argue that the appropriation of the phallus serves, ultimately, only to reiterate its primacy. The loss of the lasso (which ends violence) in favour of a sword (which is a tool of violence) removes her capacity for pacifism. Has Diaz’s Wonder Woman been denied the opportunity to create alternative, feminised forms of power? If Wonder Woman is, effectively, transformed into a man, what becomes of her pacifism, her feminism, and her queerness? Is the equipping of female characters with a phallus an effective answer to the male gaze?

To reiterate, in the battle over the representation of gender in comics, Diaz is inarguably one of the good guys, and his Wonder Woman addresses many of the problems which typically plague female characters in superhero comics. His answers, however, present certain problems which, I believe, highlight many of the flaws which surround the place for gender in the superhero genre – that, in order to avoid eroticisation or negative signifiers of femininity, Diaz’s Wonder Woman must cast aside the very things which make her a woman.