Fact: Women are problematically objectified in mainstream superhero comics.

This much is undeniable. And, to be blunt, inexcusable. But that doesn’t mean that it isn’t worth thinking about exactly how this objectification works (with an eye towards systematic attempts at educating readers about, and hopefully eliminating, the problematic aspects of such objectification, if nothing else).

This much is undeniable. And, to be blunt, inexcusable. But that doesn’t mean that it isn’t worth thinking about exactly how this objectification works (with an eye towards systematic attempts at educating readers about, and hopefully eliminating, the problematic aspects of such objectification, if nothing else).

Some might argue (and many misguided souls have tried) that males are also objectified in comics, insofar as overly exaggerated, hypersexualized depictions are as much the norm for male superheroes as they are for females. This is true, but it misses an important point: unrealistic depictions of male anatomy and garb in superhero comics plays a very different role than analogous distortions of female anatomy and clothing.

I am not going to try to sort out the differences between how males and females are depicted in comics here (it is sometime said that the difference is that superheroes are drawn the way that adolescent readers of comics want to be, and that superheroines are drawn the way that adolescent readers of comics want their girlfriends to be – this seems like a stab in the right direction, but it is both too simplistic and ignores the fact that the readership of superhero comics is much wider than the basement-dwelling, maladjusted adolescent males that the explanation seems to rely on). What I am going to do is highlight an interesting sub-phenomenon – superheroines whose hypersexualization is linked to their very real (albeit fictional) power as superheroines.

Here is one natural thought about hypersexualized depictions in general, and of superheroines in particular: Such emphasis on, and exaggeration of, secondary sexual characteristics such as breast size and waist-to-hip ratio serves to rob female characters of power. In emphasizing the superheroine’s role as a potential, and exaggeratedly desirable, partner for the male characters in the narrative (and, indirectly, for the reader), the superheroine in question is reduced to an object to be possessed, rather than a subject with her own autonomous agency and efficacy. As a result, the superheroine – super-powered or not – is rendered relatively powerless and hence relatively unthreatening to the male-dominated (both the characters and their fans) world of mainstream superhero comics.

Here is one natural thought about hypersexualized depictions in general, and of superheroines in particular: Such emphasis on, and exaggeration of, secondary sexual characteristics such as breast size and waist-to-hip ratio serves to rob female characters of power. In emphasizing the superheroine’s role as a potential, and exaggeratedly desirable, partner for the male characters in the narrative (and, indirectly, for the reader), the superheroine in question is reduced to an object to be possessed, rather than a subject with her own autonomous agency and efficacy. As a result, the superheroine – super-powered or not – is rendered relatively powerless and hence relatively unthreatening to the male-dominated (both the characters and their fans) world of mainstream superhero comics.

Now, this is, to be honest, a bit too quick. After all, the objectifying sexualization of female characters in comics can serve to emphasize a superheroine’s sexual power (although this strategy is most often applied to villainesses, since female sexual power is conventionally troped as threatening and hence evil). But sexual power – especially female sexual power – is typically treated as somehow deviant compared to the kinds of physical, economic, political, and social power typically associated with, and monopolized by, males. So the analysis of devaluing and/or rendering harmless via hypersexualization still applies.

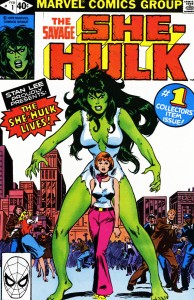

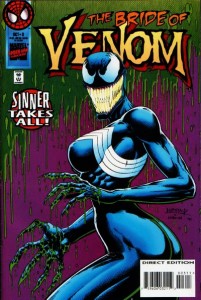

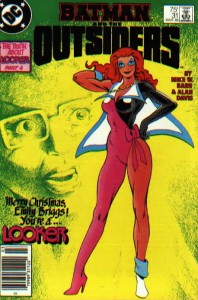

There is no doubt that the far-too-common depictions of superheroines as super-endowed, scantily clad supermodels whose primary role is to be saved by, avenged by, or romanced by their superhero compatriots has played exactly this role in the past. But there are a handful of female characters whose depictions throw a complicating monkey-wrench into the mix. I have in mind those characters whose transformations into their superpowered forms also involve physical transformations from more realistic (relatively speaking) depictions to the sort of unrealistic, hypersexualized forms at issue here. Prominent examples include the She-Hulk and the Red She-Hulk (whose transformations from human form to ‘hulked-out’ form also involve dramatic alterations to relative breast size, waist-to-hip ratio, etc.) Mary Marvel (whose transformation upon uttering “Shazam” involves morphing from a teenage girl to a mature woman), Looker (whose acquisition of superpowers also involved substantial ‘positive’ changes in her physical appearance), Titania, the Bulleteer, any female Marvel character who has interacted with any version of the Venom symbiote, etc. etc.

There is no doubt that the far-too-common depictions of superheroines as super-endowed, scantily clad supermodels whose primary role is to be saved by, avenged by, or romanced by their superhero compatriots has played exactly this role in the past. But there are a handful of female characters whose depictions throw a complicating monkey-wrench into the mix. I have in mind those characters whose transformations into their superpowered forms also involve physical transformations from more realistic (relatively speaking) depictions to the sort of unrealistic, hypersexualized forms at issue here. Prominent examples include the She-Hulk and the Red She-Hulk (whose transformations from human form to ‘hulked-out’ form also involve dramatic alterations to relative breast size, waist-to-hip ratio, etc.) Mary Marvel (whose transformation upon uttering “Shazam” involves morphing from a teenage girl to a mature woman), Looker (whose acquisition of superpowers also involved substantial ‘positive’ changes in her physical appearance), Titania, the Bulleteer, any female Marvel character who has interacted with any version of the Venom symbiote, etc. etc.

In all these cases, the acquisition of superpowers is explicitly associated with a change in appearance, from (again, relatively speaking) roughly realistic anatomy and habits of dress to explicitly sexualized, overly exaggerated forms (and, in many of these cases, there is also a marked increase in confidence and authority). As a result, it is hard to square these cases with the analysis just given of hypersexualization as a means to strip female comic book characters of power, since in these cases exaggerated anatomy and revealing clothing are explicitly associated with the acquisition of power.

As a result, we are left wanting an analysis of how, exactly, hypersexualized depiction of these characters works (especially with regard to the sorts of power these characters are depicted as having, and actually have, within the fictional narratives in question). Is it possible that these female characters somehow destabilize the status quo with regard to depictions of females, and thus represent some sort of subversive interrogation of gender roles and power in comics (intentional or not)? Are they just as worrisome as more ‘traditional’ hypersexualized depictions of female superheroes, regardless of whether they complicate our understanding of the relation between sexual objectification and power? Is this merely just a strange little quirk, unimportant in comparison to the more straightforward, and sadly extremely common, objectification found in mainstream superhero comics?

As a result, we are left wanting an analysis of how, exactly, hypersexualized depiction of these characters works (especially with regard to the sorts of power these characters are depicted as having, and actually have, within the fictional narratives in question). Is it possible that these female characters somehow destabilize the status quo with regard to depictions of females, and thus represent some sort of subversive interrogation of gender roles and power in comics (intentional or not)? Are they just as worrisome as more ‘traditional’ hypersexualized depictions of female superheroes, regardless of whether they complicate our understanding of the relation between sexual objectification and power? Is this merely just a strange little quirk, unimportant in comparison to the more straightforward, and sadly extremely common, objectification found in mainstream superhero comics?

So how do hypersexualized superhero transformations work?