Cloud Atlas

By David Mitchell

I approach contemporary science fiction with a certain wariness. Many of my friends are sci-fi/fantasy fans, and they are only too happy to recommend books. Invariably, whenever I read one of these books I’m left wondering, “Why did I waste my life reading that?” I’m not interested in reading another techno-military thriller, or a 20-volume “epic,” or a tedious story about a robot who contemplates the meaning of love. But after hearing multiple people praise Cloud Atlas, curiosity got the better of me. I’m glad to say that it wasn’t any where near as bad as I feared. I still didn’t like it , but I don’t feel like I’ve wasted hours of my life reading it. So that’s progress.

Cloud Atlas consists of six stories arranged in chronological order through the first half of the book, then the first five stories are revisited and concluded in reverse-chronological order in the second half. The stories are:

The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing – circa 1850, a diary written by an American traveler who spends time on the Chatham Islands before sailing for home. Much of the story describes the impact of Western colonialism on Pacific islanders, particularly the Moriori, who were nearly destroyed by a combination of Maori invaders and European diseases. Ewing is a relatively decent man, but he unthinkingly embraces the prejudices of his era until he meets a Moriori stowaway named Autua. Ewing saves Autua’s life, and the latter returns the favor by saving Ewing from the villainous Dr. Goose who planned to rob and murder Ewing.

Letters from Zedelghem – a series of letters written in 1931 by Robert Frobisher, an aspiring composer who flees his debts in England and moves to rural Belgium. There, he finds a position as the understudy to a famous but ailing composer. Robert is a bit of a rake, and seems poised to exploit the composer and his lusty wife for all they are worth. But his fortunes turn for the worse after a falling out with his employer.

Half Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery – a crime story set in 1975 California. Luisa Rey is a journalist working for a trashy tabloid who stumbles upon a major scandal involving a dangerous nuclear power plant and a murdered whistle-blower.

The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish – a contemporary comedy about an aging publisher who flees his troubles and inadvertently ends up in a retirement community. The community is run like a prison and the aging residents are treated little better than criminals. Most of the story details Cavendish’s escape attempts.

An Orison of Sonmi-451 – a dystopian sci-fi drama set sometime after a global nuclear war. Korea escaped destruction, but it is now ruled by a totalitarian-capitalist regime that relies on artificially-grown slave labor. Sonmi is one such slave, but she experiences an “ascension,” becoming fully self-aware and joining a rebellion. Sonmi is later captured and narrates the story to her interrogators prior to her execution (the orison is a recording device).

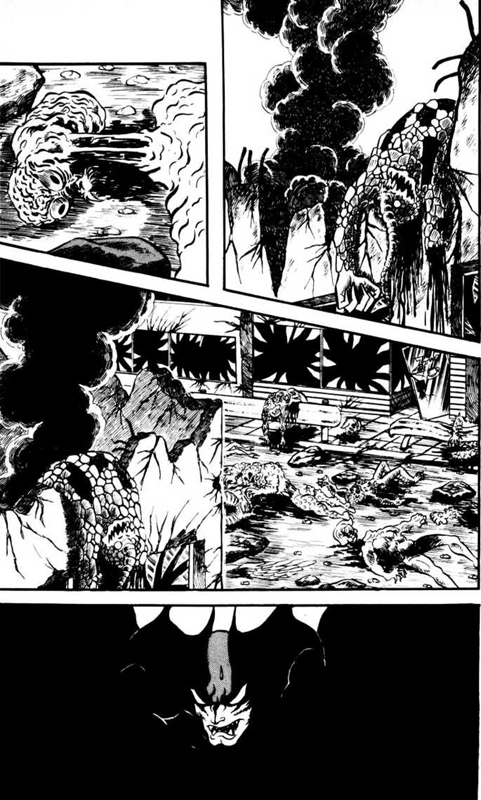

Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After – a memoir by Zachry, a Hawaiian tribesman who lived in a primitive farming community long after a nuclear war wiped out most of humanity. Zachry assists Meronym, one of the last remnants of a technologically advanced society, in gathering useful information. Zachry is eventually saved by Meronym after his village is wiped out by a more violent tribe.

The stories are interconnected in several ways. All the lead characters except Zachry possess the same comet-shaped birth mark, and Mitchell has acknowledged that they are a single reincarnated soul* (Meronym is the last reincarnation). Each story also acknowledges the existence of the chronologically earlier story. Frobisher reads Ewing’s journal, Luisa reads Frobisher’s letters, Cavendish reads a book starring Luisa, Sonmi reads a book about Cavendish, and Zachry encounters the orison that recorded Sonmi’s confession.

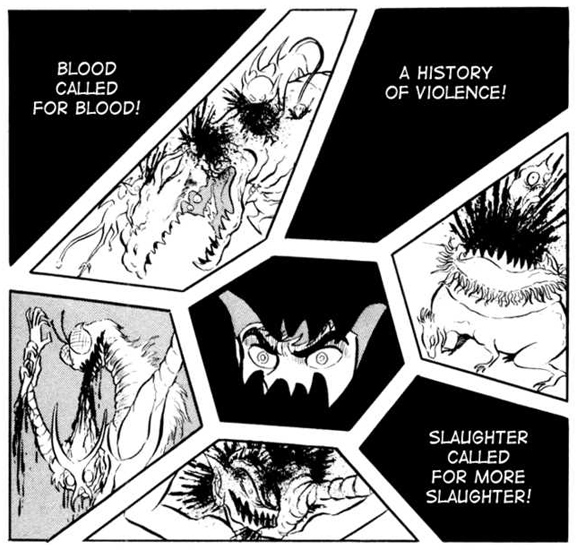

And there are themes common to all six stories, particularly the universality of violence, conquest, and exploitation. Ewing is a witness to Maori and European imperialism, and he is personally the victim of deception and violence. Frobisher is exploited by his employer. Luisa is nearly murdered by the corrupt owners of the nuclear plant. Cavendish is cruelly treated by the “caretakers” at the retirement community. Sonmi is enslaved, manipulated, and finally executed by an oppressive state. And Zachry’s entire world is destroyed by a predatory tribe. But Mitchell also acknowledges a gentler humanity that can triumph over our baser instincts. Autua saves Ewing, just as Meronym saves Zachry several centuries later.

For Mitchell, the triumph of good over evil is dependent on story-telling. This is particularly evident in Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After. As they lynchpin story, it binds the chronological narrative to the motifs that reoccur in the other five stories. It largely succeeds in highlighting Mitchell’s themes about human predation versus the “ascension” of the human spirit. Much of the story involves Zachry and Meronym fighting or evading the barbaric Kona tribe. Also, while Zachry’s tribe is more peaceful, he himself repeatedly struggles with violent impulses. At one point, Zachry actually has a conversation with the Devil (Old Georgie) and barely resists the temptation to murder Meronym. And Zachry’s tale suggests the moral value of story-telling. Zachry is the only survivor of a brutal attack on his tribe, and he eventually re-settles with Meronym’s people, who record his memories. His spiritual struggles and moral triumph serve as a inspiration to the surviving humans.

This theme re-emerges at the end of the second half of the Adam Ewing story (which is also the end of the entire novel). Ewing narrowly escapes murder at the hands of a (white) doctor who embraces a nihilistic, predatory philosophy. Ewing is saved by Autua, a dark-skinned ex-slave. These events cause Ewing to rethink his entire worldview, and he decides to become an abolitionist. In his words, “If we believe humanity may transcend tooth & claw, if we believe divers races & creeds can share the world … such a world will come to pass.”

So there are plenty of ideas bouncing around the book, and its division into six stories allows Mitchell to explore those ideas in six different genres. In each story, Mitchell demonstrates basic skill as a genre writer, whether he’s writing faux-memoir, mystery, or science fiction. In theory, Cloud Atlas should be an exciting and challenging book. In practice, the book fails to live up to its pretensions, largely because Mitchell’s ideas are not as profound as he seems to think they are. To summarize the main points of the book: if people choose to be good, then the world will be a better place. And story-telling is an effective way to convey moral lessons. The obvious response to these points is “No shit!” People have been well aware of these insights for at least the past two thousand years.

A more interesting observation might involve asking why people continue to do immoral things despite the countless stories intended to teach a moral lesson. If Cloud Atlas is any indication, Mitchell’s answer would be that humans are naturally predatory (they have an inner Old Georgie) and so there will always be at least some people who are violent, cruel, and selfish. That’s partly true, but it elides the fact that many violent, cruel, and selfish people nevertheless consider themselves moral, and they may even behave with kindness in a different context (for example, in the treatment of their own family). A sophisticated view of morality would have to look beyond a simplistic predator/victim relationship.

I don’t see much moral complexity in Cloud Atlas. The “good guys” are always likable, POV characters. They may be flawed, but their flaws are surmountable or at least forgivable. Ewing starts off as a racist, but he has an epiphany and embraces racial egalitarianism. Luisa Rey pursues journalistic truth and saves lives. Sonmi achieves greater self-awareness and defies a totalitarian state. Zachry resists temptation. Even the self-absorbed Frobisher isn’t that bad a guy, and he ends up being rather sympathetic in his final days.

The “bad guys,” on the other hand, are a uniformly reprehensible lot with no redeeming qualities. Dr. Goose is a psychopathic murderer. The businessmen in Half-Lives are almost comically villainous. The “caretakers” encountered by Cavendish are petty tyrants. And of course there is an oppressive state and the violent Kona tribe in the last two stories. Because Mitchell leans toward a simplistic, good vs. evil dichotomy, he can’t offer deeper insights about human morality. And without these insights the stories can only be described as forgettable genre works.

For example, Half Lives was a crime thriller, so Mitchell could draw ideas from an enormous collection of works. But while Mitchell replicates the basic formula and rhythm of a crime thriller, he doesn’t create a particularly compelling or memorable story. It’s an “airport novel” with a few liberal biases: corporations are evil, nuclear power is bad, journalists are noble heroes, etc., etc. All that righteousness becomes rather tedious, and it weighs down what would otherwise be a decent plot. Nor does it help that Luisa Rey is a dull heroine who stumbles through her own narrative while side characters perform all the heavy lifting.

An Orison of Sonmi-451 had far greater potential, as it borrows concepts from Huxley, Orwell, and the other great writers of dystopian fiction. In one sense, it’s an extremely derivative story, and Mitchell openly acknowledged his inspirations (primarily Brave New World and 1984). Being derivative doesn’t necessarily have to be a mark against it, as writers are constantly stealing ideas from each other. But Mitchell only steals the surface of ideas, and he adds nothing new to the genre. Huxley was interested in the relationship between eugenics and class (mostly because he belonged to a a family of eugenicists), while Orwell was interested in propaganda, particularly the manipulation of language. Mitchell touches a little on eugenics and propaganda, but he does little more than regurgitate older ideas. He’s far more interested in writing a story about a heroic slave who triumphs over her oppressors, even from beyond the grave. Though she was executed, the novel suggests that Sonmi’s confession become public knowledge and inspire a slave rebellion. She even comes to be worshiped as a goddess in Zachry’s time. It’s so predictably uplifting I wanted to puke. I’m not suggesting that the triumph of good over evil is objectionable per se, but it seems absurd to take the ideas of dystopian futurists and tack on a happy ending straight out of a Hollywood blockbuster.

Though the happy ending approach may explain why Cloud Atlas will soon be in a theater near you.

_________