Ever since the dawn of time, college undergraduates have started their term papers with the phrase “ever since the dawn of time”. Another thing that’s been happening since then is debates between superhero comics fans about what to call the current “age” of comics. The latest discussion is here, in a roundtable at Comics Alliance involving various comics scholars and critics, which dares to ask the question whether these our times should be called the Second Golden Age, the Prismatic Age or the Second Dark Age.

No, really.

Let’s get the obligatory snobbery out of the way upfront, because I know you’re all thinking it: this is some embarrassing shit to ask grown-ups. It’s like asking a bunch of art historians “what code do you think Da Vinci was using in the Mona Lisa?”, or a bunch of philosophers “on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being really awesome and 10 being totally awesome, how awesome is Ayn Rand, and is she more awesome or less awesome than L. Ron Hubbard, ranked on the same scale?

“Also, write your answer in the form of a sequel to Atlas Shrugged.”

All of the scholars/critics in the Comics Alliance article push back, in one way or another, against the presuppositions of the question, with Charles Hatfield voicing the most articulate critique. Said critique will come as no surprise whatsoever to most readers of this site or, indeed, to anyone who’s ever given it a cursory thought — viz. that the division of comics history into Ages Golden, Silver, Bronze, etc. based entirely on the various adventures of such beloved intellectual properties as Ma Hunkel (the original Red Tornado), Brother Power the Geek and Skate Man is risibly parochial. It’s also ridiculous, inane, dunder-headed, fatuous, asinine, feeble-minded, nincompoopish and numskullerific.

(Undergraduates also like to use the thesaurus.)

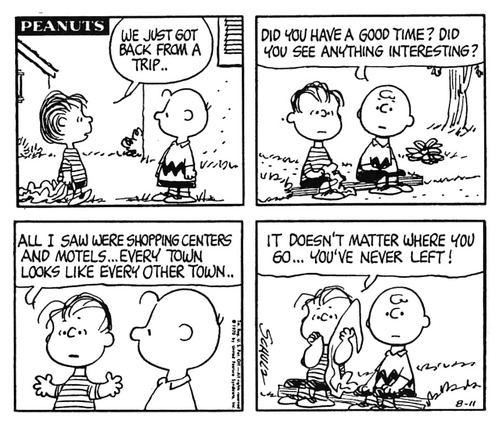

Categorising the entire history of “comics” based on the developments of this small subgenre is like categorising the entire history of Western narrative art on the basis of developments in Sexy Vampire Fiction. Which, I guess, is probably something they do on the bulletin boards at lestat-l’estate.com and millsandfangs.org: which exact work marks the transition between the Hammer Lesbo Age and the Rice Homo Age? Should 1997-2004 be labelled the Angel Age or the Spike Age? If Edward Cullen and Eric Northman hooked up, who would be the top?

Me, I’m on Team Morbius the Living Vampire.

Anyway, to flog this dead horse any further would be otiose. If you have to be told why it’s silly to parse comics history this way, there’s no point telling you. But that’s not why I’m writing this post. No, I’m writing this post to declare that, even if we go along with this ridiculous, inane etc. division of history, the labelling still doesn’t make sense by its own lights.

And the reason is simple: most “Golden Age” superhero comics — including many of the key texts — are, if you will pardon my French, un complete et total piece de merde.

No one could possibly think that the representative and historically important superhero comics from the 40s (the “Golden Age”) are, on the whole, better than the analogous superhero comics from the “Silver Age” of the late 50s and early 60s. No one. The Silver Age has Carmine Infantino, Steve Ditko, Murphy Anderson, Curt Swan, Gil Kane, Joe Kubert and Stan Lee all at their prime working on superheroes, and Jack Kirby at one of his primes. The Golden Age, to be sure, has Will Eisner, CC Beck, William Moulton Marston and HG Peter, Jack Cole and Bill Everett…but also “Bob Kane”, Siegel and Shuster, Paul Gustavson, early Kirby and Simon, and a million other inept swipes from Alex Raymond.

So, if we absolutely have to have this arbitrary and artificial division of genre-specific material into “ages”, can we at least use the right metaphor? Superhero comics did not degenerate from a fabled, prelapsarian Eden; they evolved from primitive beginnings into a higher and nobler state. It’s not Golden to Silver, it’s Stone to Iron.

…Come to think of it, though, even calling it the Stone Age is being kind to 40s superhero comics, and unkind to stones. I’m just thinking out loud here, but what tools did our hominid ancestors use before stones? Okay, in the Stone Age, they made crude axes out of, well, stone (duh), but before that were they making even crummier axes out of spit and dirt? Was there a Dirt Age? Was there an even earlier Leaf And Stick And Some Bits Of Clay I Found By The River And I Sort Of Smooshed Them All Together And Made A Pretty Good Lump Of Crud To Throw At Somebody Age? Was there an even earlier age where they threw faeces at one another like chimpanzees? Can we call it the Faeces Age? Can I make it through one whole post without resorting to toilet humour?

THE ANSWER IS NO.

(Self-promotional PS: I further discuss the shittiness of the “Golden Age” here and the embarrassment of superherocentric historiography here).

Image attribution: Cover taken from the invaluable comics.org