It’s easy to knock corporate super-hero comics. There’s the relentless, unthinking sexism; the apparent paucity of fresh concepts; the tendency to confuse horrific violence with thematic sophistication (and the related inability or unwillingness to address younger readers); the summer crossovers that so often and so transparently put sales figures ahead of internal coherence or aesthetic quality; and the frequent reboots, which may once have been justified as a way of shedding the weight of unwieldy continuity, but now smack of greed, desperation, and cluelessness in about equal measure.

These various problems can be diagnosed as symptoms of a fundamental disrespect for the comic book audience at the corporate level. But creators, too, are often subjected to this same disrespect, even as they continue to labor within the constraints of the current system. Probably no one reading this needs to be told about the historic injustices that have arisen out of the “work-for-hire” production model; nor is it hard to imagine the chilling effect that this model must have over time for even the most successful practitioners of the genre. (Indeed, it’s probably no coincidence that many of my personal favorite writers and artists often seem to do their best work when engaged with creator-owned projects; by comparison, producing comics under a “work-for-hire” contract must feel like swimming with weights.)

The writers and artists who do manage to produce work of consistent quality within the corporate system, on a monthly basis, sometimes for years on end, have therefore beaten some long odds, in my opinion. And perhaps in such circumstances it is all the more important to offer commendations when commendations are due.

I am here, then, to sing the praises of Brian Michael Bendis and his various co-conspirators for their work on Marvel’s Ultimate Spider-Man.

First, and for the tiny handful of you who might not know this (“Hi, Mum!”): Marvel’s so-called Ultimate universe was initially conceived back in 2001 or so, as a way of re-starting the adventures of the most well-established Marvel characters from their origin stories — with a clean-slate, as it were. The official reasoning was that creators would no longer be tied to decades of prior continuity, and that this would also encourage new readers to jump on board. Less often acknowledged, but probably equally important was the opportunity to jettison aspects of the older narratives that had simply dated. For example, in the 1960s, Stan Lee’s default “origin story” involved some sort of inadvertent exposure to radioactivity. But radioactivity is a less mysterious concept today than it was sixty years ago. We don’t expect it to give us superpowers; we do expect it to give us cancer. Consequently, in the Ultimate universe, corporate and government sponsored experiments in genetic mutation — almost always carried out at the behest of the military — have taken up the plot function that was once fulfilled by radioactive “isotopes.” (And there’s probably a whole essay of the cultural studies type that could be written about the political and cultural implications of this particular shift of emphasis within the superheroic fantasy, but I’m not going to write it.)

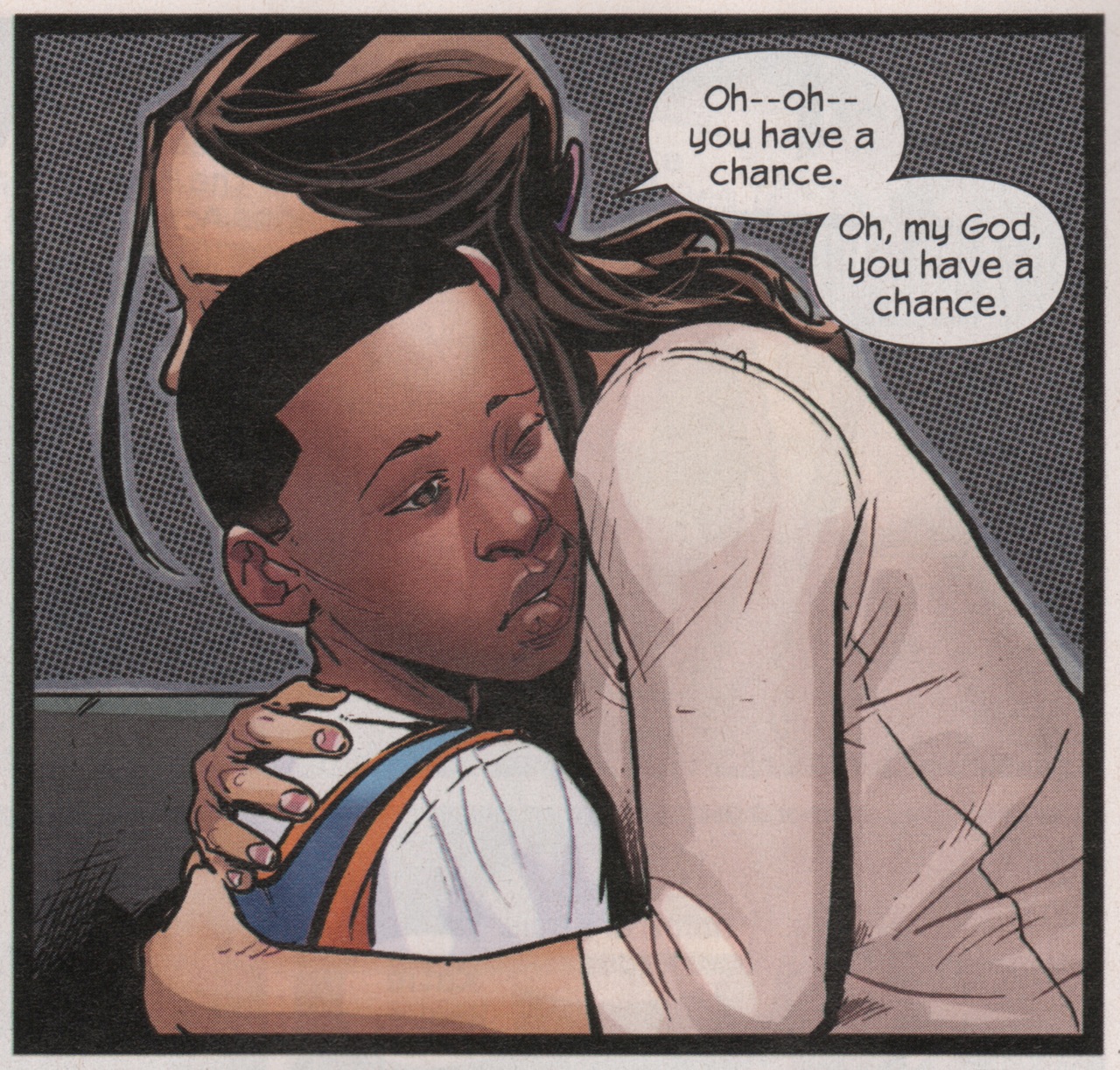

Within the current continuity of this Ultimate universe, a teenager named Miles Morales has recently taken up the webbed mantle and power-and-responsibility mantra of Spider-Man. Miles resembles his predecessor, Peter Parker, in many ways — he’s intellectually gifted, ethically centered, and terribly young to be a hero — just thirteen years old, in fact. But unlike Peter Parker, who was obviously Caucasian, Miles is the child of an African-American father and a Hispanic mother. Marvel’s decision to re-boot one of their flagship characters as a person of color has generated a fair degree of media interest, and even seems to have ruffled the feathers of a few right-wingers and white-supremacist types. I’ll say a bit more about that, but for now I just want to note that this is just one of the reasons that I like the comic. Here are some others.

Within the current continuity of this Ultimate universe, a teenager named Miles Morales has recently taken up the webbed mantle and power-and-responsibility mantra of Spider-Man. Miles resembles his predecessor, Peter Parker, in many ways — he’s intellectually gifted, ethically centered, and terribly young to be a hero — just thirteen years old, in fact. But unlike Peter Parker, who was obviously Caucasian, Miles is the child of an African-American father and a Hispanic mother. Marvel’s decision to re-boot one of their flagship characters as a person of color has generated a fair degree of media interest, and even seems to have ruffled the feathers of a few right-wingers and white-supremacist types. I’ll say a bit more about that, but for now I just want to note that this is just one of the reasons that I like the comic. Here are some others.

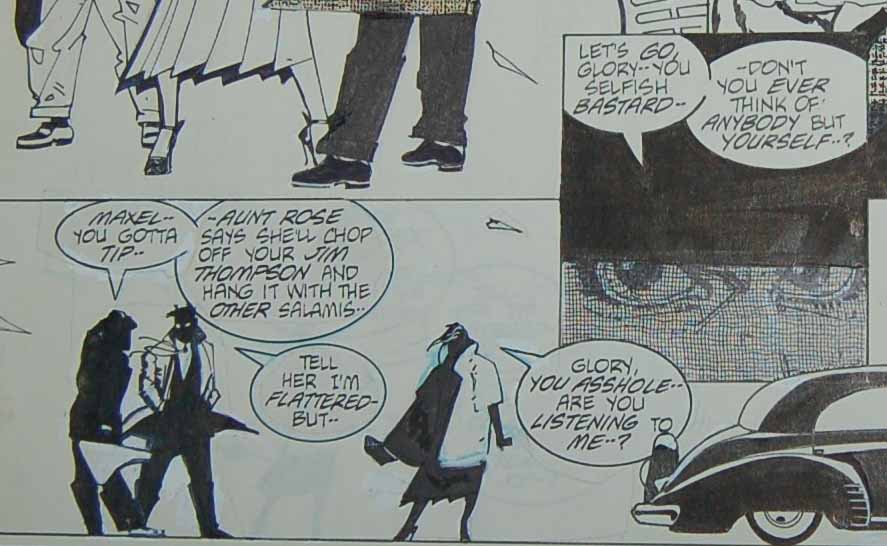

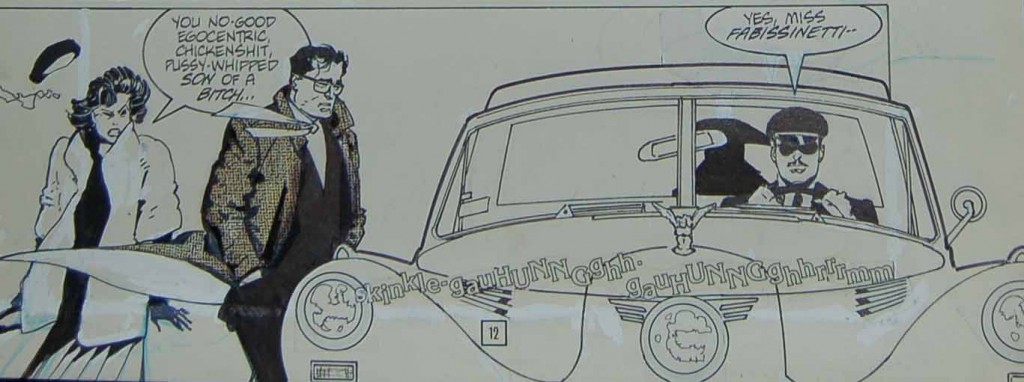

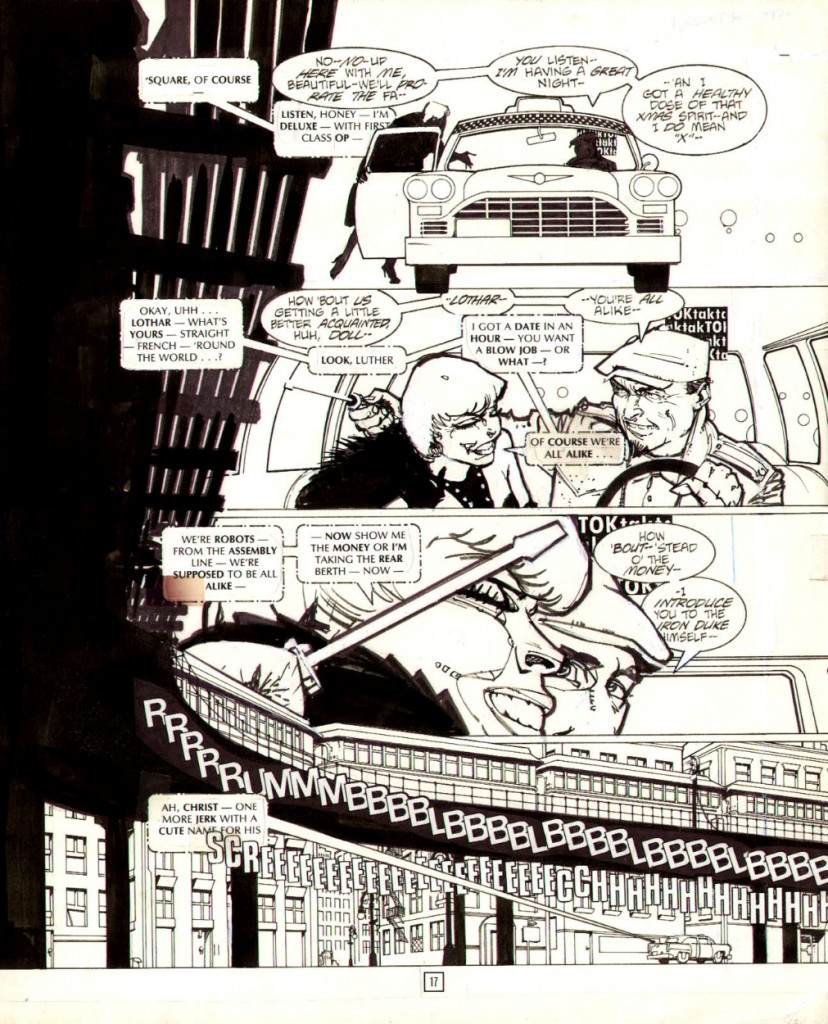

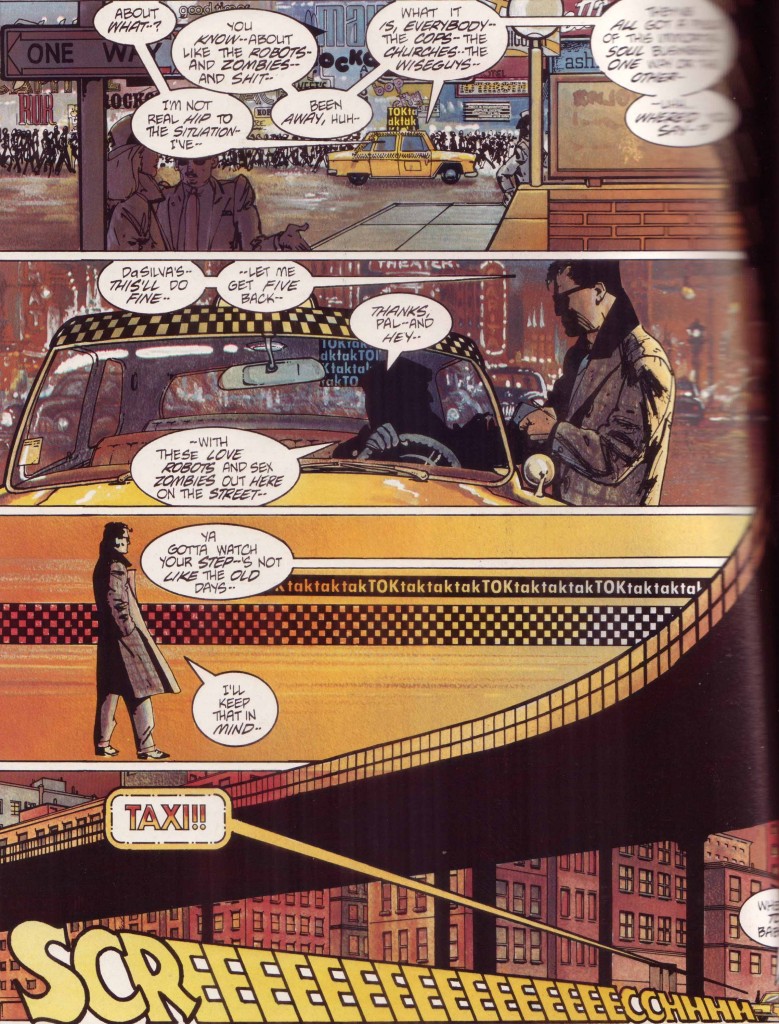

1) It is a great “all-ages” book — or a great 10-years-old-and-up book, at least. This is important, because there are just not that many quality genre comics that can engage both younger readers and adults out there these days. In fact, most of my favorite current genre titles (Casanova, Criminal, The Sixth Gun, Scalped) are not appropriate for kids at all.

It is ironic that great comic books for younger readers should nowadays be so very hard to find, given the original target audience for the medium; but perhaps it should not be much cause for surprise. Quality children’s literature has always been unusual, after all — which is partly why works like Alice In Wonderland or the Oz books or Where The Wild Things Are become objects of veneration. The really good stuff is rare as hens’ teeth.

I’m not saying that Bendis’s work on Ultimate Spider-Man is an achievement to be ranked alongside Carroll’s or Baum’s or Sendak’s. That would hardly be comparing like-with-like, after all. I’m simply saying that there are only a tiny handful of quality monthly genre titles that can engage an adult audience while remaining appropriate for younger readers — and Ultimate Spider-Man is one of them. (If you are looking for others, Atomic-Robo and Princeless are also pure, joyous fun, but of course neither of them are superhero books. In fact, it really would be hard for me to name another superhero title with the “all-ages” appeal of USM right now.)

2) While it is easy (and often appropriate) to be cynical about any gesture made by Marvel or DC towards traditionally marginalized members of the readership, I think Bendis’s decision to take one of Marvel’s most recognizable characters and recast him as a person of color is not only entirely commendable, but has also been (thus far) very well handled. Yes, Marvel and DC can always create “new” non-Caucasian heroes, but the fact is that if the marquee, iconic figures are always white, well … the marquee, iconic figures are always white.

And yes, it is possible to belittle or undermine this move by saying it’s “only” the Spider-Man of the Ultimate universe that we are talking about — as if that makes this a less “real” change. But even leaving aside the silliness of arguing which version of Marvel universe is more “real,” I think that the people who are inclined to say this have not been following the comics for some time, and therefore don’t realize that the Ultimate universe has now been established for well over a decade. For a lot of readers, the Ultimate Marvel Universe IS the “real” Marvel universe. What’s more, the recent Marvel movies owe at least as much to the characters as they are presented in the Ultimate line as they do to the regular 616 line. So this is not the equivalent of a “what if” or “imaginary” story in which someone other than Peter Parker gets bitten by that magical spider. It’s a much bigger deal than that.

Nor can the invention of Miles Morales be written off simply as an attempt to boost flagging sales with a headline grabbing plot twist. While comic book sales in general are apparently regarded as dismal, Ultimate Spider-Man has (I believe) been the most consistently successful Ultimate title. It’s certainly the longest running — and I’ve personally enjoyed it more than almost any of the Spider-Man books published in the 616 universe for the last decade. (I’ll admit that Bagley’s art put me off for quite a while. But I gradually got over it, and eventually came to appreciate his considerable storytelling skills, even though I still generally dislike the details of his faces and figure work.) So this wasn’t a “hail Mary” pass, or a last ditch effort to save a dying title. On the contrary, it appears to have been a thoughtful, considered, and even potentially risky move, given the relatively high profile of the book in question.

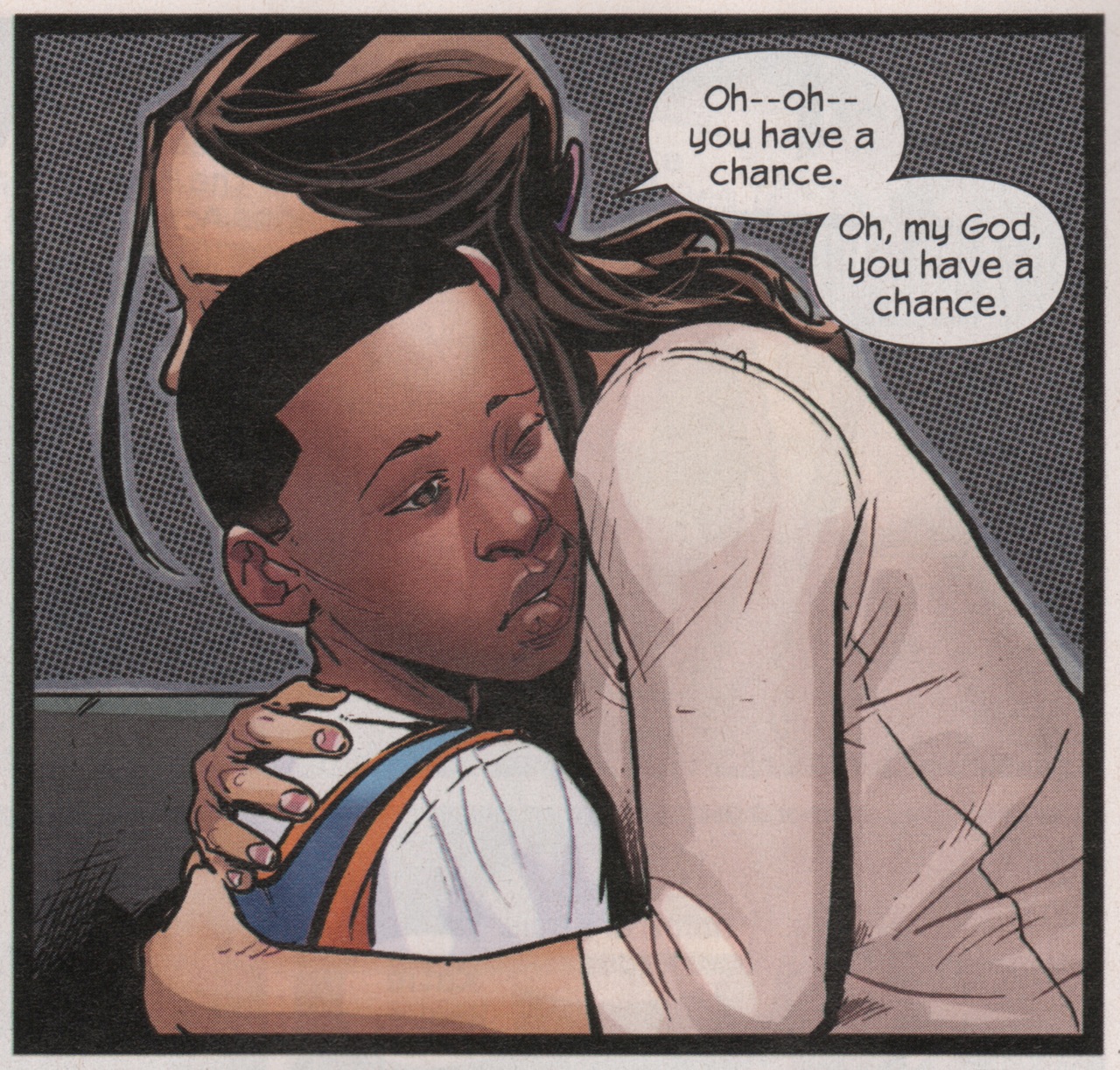

When we first meet Miles and his parents it is at a “lottery” for places in an elite private school. They are surrounded by other anxious parents and children, and the importance of this lottery for these families — as a possible route for their children out of the broken public school system, and into the middle class — is made very clear. When Miles’s number comes up — in a nice touch, the same number is marked on the genetically modified spider that will later bite him, and give him powers — his mother embraces him weeps in relief: “You have a chance. You have a chance.”

By means of this “school lottery” subplot, then, larger themes of race- and poverty-based exclusion have been placed at the center of the new Spider-Man’s origin story. This doesn’t make USM a political tract. But it suggests that Bendis understands something very important. He understands that the history of racism — and the attendant problem of the representation of race in various forms of media — is not simply rectified by a change in the hero’s pigmentation. Miles Morales’s experiences also need to be different from Peter’s — and not just because he is a different person, but also because he is a person-of-color living in a culture where race relations are vexed (to put it laughably mildly).

Those who haven’t read the title, please don’t get me wrong. Miles’s race is not THE only or even the central issue in the comic; but it is part of the fabric of his experience — just as it should be.

This is tricky stuff to pull off, in any medium, in any genre. So far it seems to me Bendis is getting it absolutely right. He deserves praise for that.

4) Finally, the mere creation of Miles Morales seems to have genuinely pissed off Glenn Beck. Of course, Beck is the king of manufactured outrage — but if Bendis did manage to get under Beck’s toad-like-skin for even a minute, that only makes me want to cheer him on.

So, to come back to my initial observations: it seems to me that there’s a lot of instinctive critical hostility out there online (and also in academic circles) among comics critics when it comes to the superhero genre, and some of it — maybe even most of it — is justified.

Nevertheless, I can’t help feeling that some of this critical hostility is misplaced — almost like what some philosophers would call a category mistake. Perhaps the confusion originates in the confused status of the genre itself, as something that began as a form of children’s entertainment, and which therefore gets into all kinds of difficulties when it aspires to “adult” sophistication. But just as it makes no sense to criticize Wall-E for not being Vertigo, similarly, it makes no sense (to me) to attack superhero comics for being superhero comics. (For being badly drawn or badly written, yes; but for conforming to certain well-established genre conventions, no.)

To put it another way: I don’t expect a Bendis superhero comic to deliver the kind of introspective reflections on parenting and childhood that I expect from, say, the new Alison Bechdel book (which I recently purchased and am keen to read). I don’t expect his representation of high school to mirror that of an autobiographical cartoonist such as, say, Ariel Schrag. But within the established conventions of the superhero genre, I find his work consistently entertaining, and often brilliant. And I think he deserves the highest praise not only for his current work on Ultimate Spider-Man, but also for his previous decade of scripts for the title.

In fact, over the course of his long USM run, Bendis has written some of the only superhero comics that have given me the same “fall-into-the-page” experience that I used to get from the genre when I was a kid (and none of the comics that I read as a kid still work for me THAT way — even when I can find other things to appreciate about them). Inspired by the latest issues, then, I recently re-read some of those earlier comics from the run — Bendis’s version of the Peter Parker era. In all honesty, I wasn’t planning on writing critically about these comics, or even thinking too hard about them. I was too tired for anything that I felt would be more “demanding” — I was just looking for a bit of escapist fun, after a long day teaching (both Hamlet and Watchmen, as it turns out — though not in the same class, I’m sorry to say).

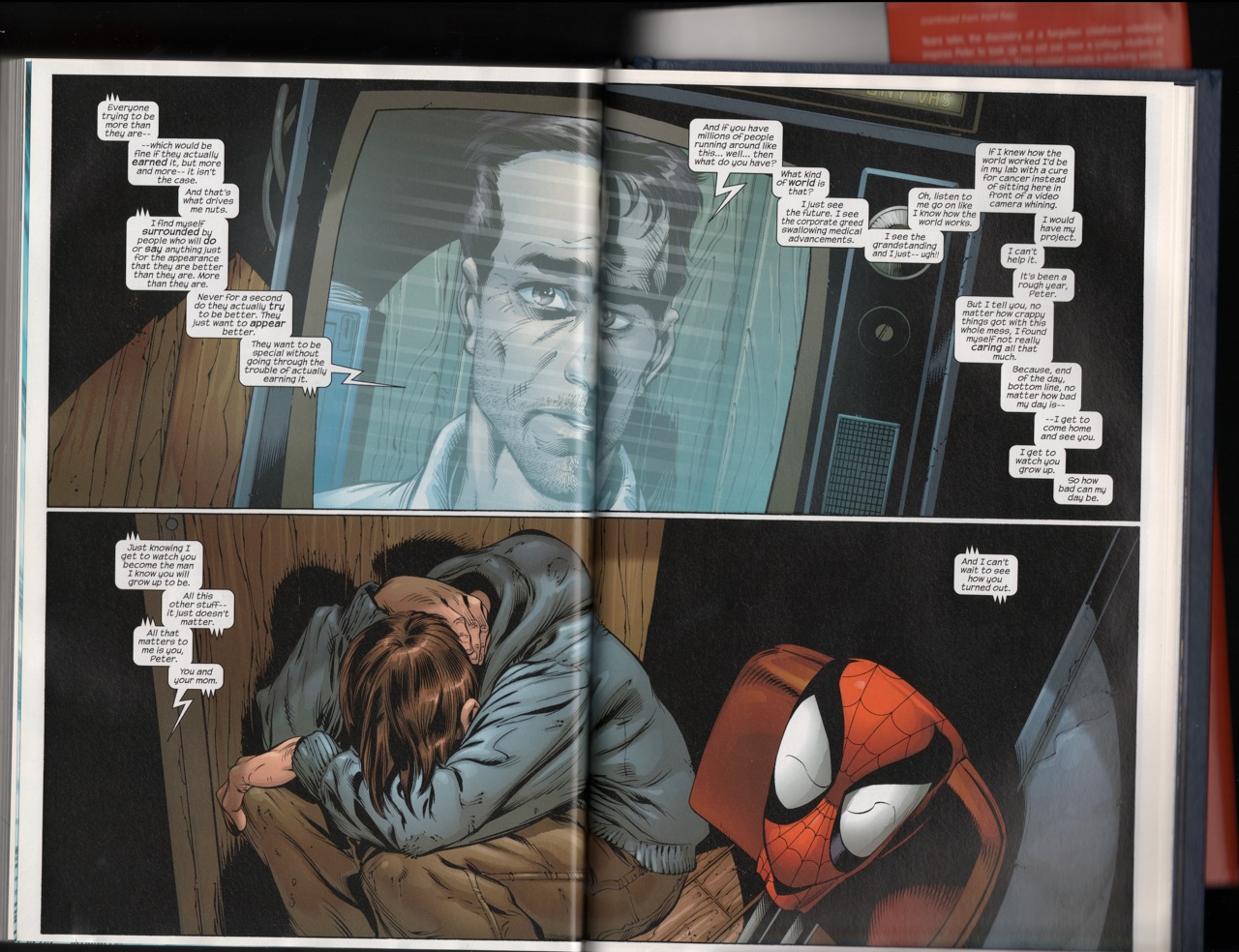

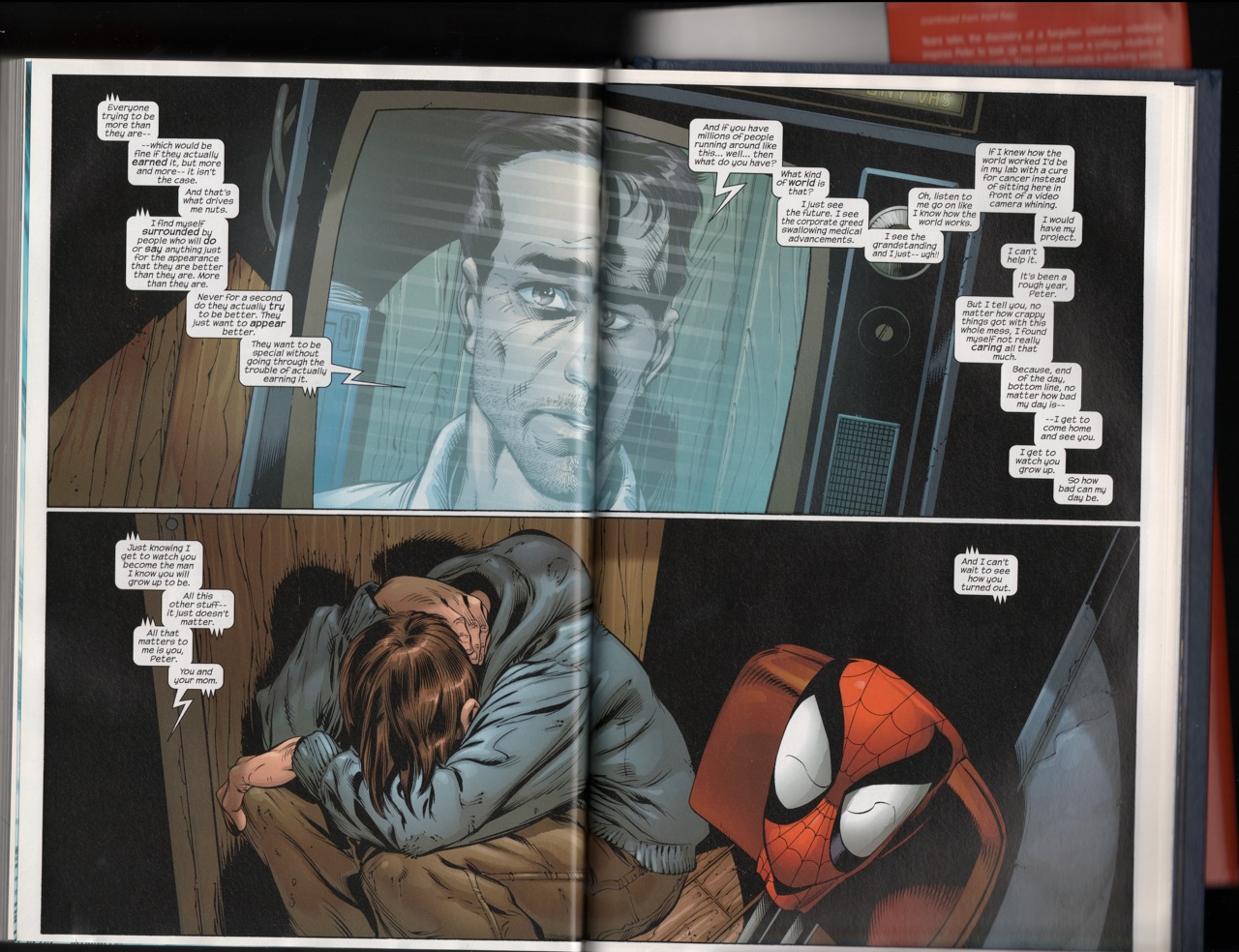

I picked the Venom arc — Venom being a character I never liked in the original Spider-Man universe (an antipathy apparently shared by Bendis himself), but found myself enjoying in his Ultimate incarnation. In Bendis’s revision, the Venom project is something that Peter Parker’s father was working on before he died — a piece of medical research that Richard Parker ends up not owning because (get this) he produced it under a “work for hire” contract for an evil corporation. The temptation to read this as a self-reflexive commentary on the exploitation of comic book creators is surely irresistible. The story arc ends with a sequence in which Richard Parker speaks from beyond the grave to his son, Peter, via an old VHS tape. He talks about the feelings of impatience and creative ambition that first led him to sign this flawed “work for hire” contract, and acknowledges that not owning his ideas sucks. But he also insists on the importance of taking responsibility for one’s own mistakes. He concludes by telling Peter how much he loves his family — and how having a family at all finally helps him deal with the frustrations he has encountered in the world of his work. Peter, who has just endured a particularly emotionally punishing series of adventures, is depicted listening to his father with his head bowed. It’s not the portrait of a winner. On the contrary, Peter seems utterly crushed. But as readers we cannot help but nod in assent when Richard Parker expresses hopeful pride in his young son, and faith in the kind of man that his son will become.

The emotional tone of this moment is complex. It poignantly and powerfully evokes our admiration for the hero not in his moment of triumph, but in the depths of his despair. And it moved me to reread this sequence. Indeed, it moved me as much as anything I had encountered earlier that day in the classroom, teaching the works of Shakespeare and Moore.

The critical cliché would be to claim that at moments like this in his Ultimate Spider-Man run Bendis has “transcended the genre.” But fuck that. I LIKE genre work, and I wouldn’t patronize any great genre writer with this supposed compliment. Brian Michael Bendis doesn’t need to transcend the genre to transport me.