This article was originally posted on Okazu, as a discussion of scanlation in general, but this discussion is even more relevant to “arty,” more grown up comics, which will, by it’s nature, appeal to a smaller audience than anything mainstream. The smaller the potential audience, the smaller the potential market. Because it’s hard to get what they want to read, this audience created scanlation to serve their needs.

Here is a history of scanlation – and a suggestion for a solution that can be most effective for the titles least likely to reach their market with the current distribution models.

****

Scanlation – the widespread, illegal act of scanning in books/comics/manga, sometimes translating them into another language and distributing them for free through digital formats and technologies.

Scanlation is, everyone will agree, a big problem. The comics publishing industry is losing sales even as downloads of scans hits numbers that most comics publishers can only dream about. The comics/manga journalists agree, talking as they do to the publishers and creators – who feel particularly angry in regards to the wholesale refusal of their “fans” to respect their IP rights. And the pundits who discuss the quickly disappearing value of copyright and IP ownership agree.

Cartoonist Scott Adams recently blogged on this disappearing economic value of content as it becomes easier to search for – without necessarily being involved in a ‘scan’dal himself. (Adams allows free and fair use for all his work, and encourages fans to do mashups, parodies and original work based on his material.

So, if everyone agrees that scans are bad, why are they so rampant? How can we fix this pervasive problem?

In order to fix the problem, we have to step back and realize that scanlations are not the “problem” – they were the solution.

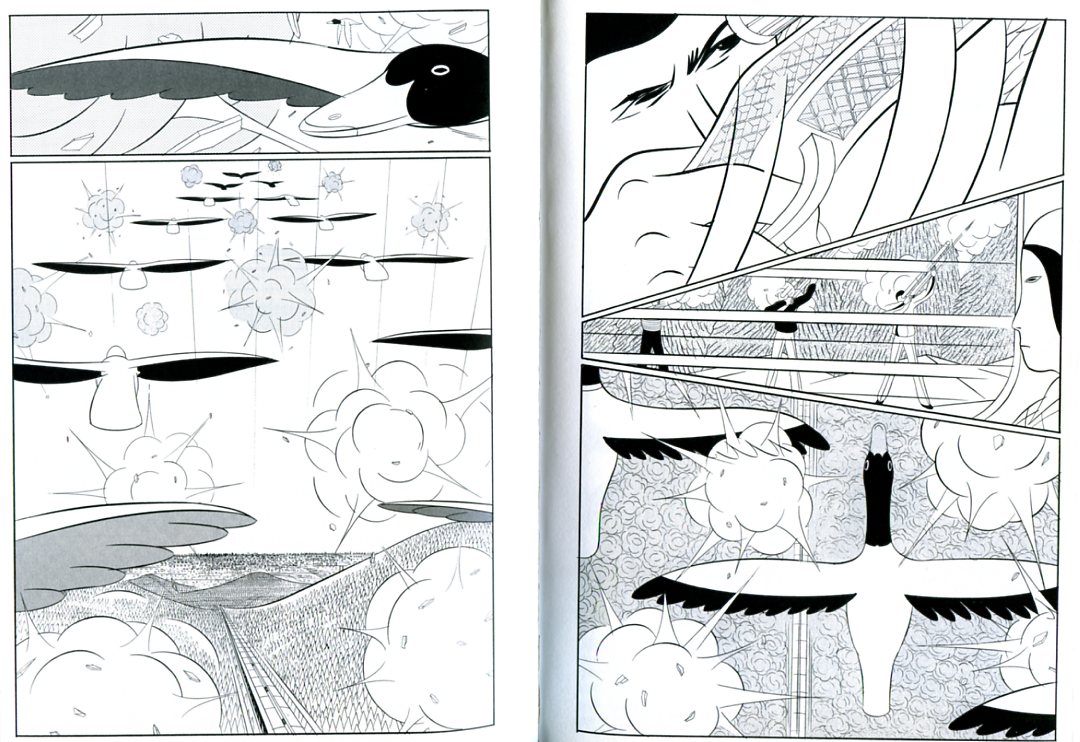

I’m speaking here as a fan of manga, comics from Japan. When I started to read manga there were – to be generous – very few titles licensed and translated.

The fans who loved manga saw the problem clearly – there was a lot of cool stuff being drawn in Japan and very little of it was translated into English. So, they formed groups called “circles” – passionate volunteers who pooled skills and resources into scanning in manga and translating them. This way, they could share the series they loved with other people who would never otherwise get a chance to read them. It was (and largely still is) a love for a title that leads a person to scan it – not a desire to harm, but a deep desire to share and expand the audience.

Scanlation was the solution to the problem. It wouldn’t hurt anyone – none of those books (or anime series) were ever going to make it over here, so no harm, no foul. At least one person had to buy the book (or VHS tape) in order to render and scan it, so there was at least one additional sale to “pay” for the work. No scanlation circle ever made a cent on their efforts. They gave their love away for free, so they could call it fair use. And they were very specific – if you paid for a version of their scans or subs, you were ripped off and you were committing a copyright violation.

Then the digital revolution really hit and suddenly more series than ever were being scanned and subbed. It isn’t hard to get a scanlation – all one needs is a browser and a search engine. What had formerly been distributed to dozens of people was now being distributed to thousands or tens of thousands worldwide. Hits on popular scanlation aggregation websites go into the millions, bringing at least one such site onto Google’s list of top-visited sites.

And, in the middle of this, distribution companies started to license more series than ever. But now it was even easier to scan than before – often a scanned raw version is available, so no original copy is bought. Scanlators can put out a whole volume in days in just about any language a group might want. And the more popular, the more ubiquitous the content becomes, its economic value drops ever closer to zero.

What we need now is not a solution to the problem, but a solution to the solution.

***

Scanlation affects three entities. The fans, for whom it is uniquely an excellent – and elegant – solution. The publishing companies, for whom it is a strongly negative factor in both incentive to license and in actual sales. And the creators, who are often clueless about the scale of the issue, feel helpless and angry if they are aware of it, and whose bottom line is the most damaged by it.

For the sake of meaningful discussion, I am going to ignore the existence of overtly criminal scanlators and subbers. These are people who illegally distribute books and series that are legally licensed and available in their country. They know they are committing a criminal act and do not care. Their audience is either naïve and unaware that these distributors are illegal – or they are aware and, like the scanlators, do not care. These people are engaging in IP theft and copyright violation with criminal intent. They are not relevant to this discussion, in which we are going to address the “problem” created not by the desire to steal – but by the desire to share.

I say that scanlation is a solution. The problem it solved was “things I want to read are not licensed for my country.” This was true in 1998 and now, in 2010, it is largely *still* true. I follow a genre called Yuri (lesbian-themed stories), which has had a Renaissance in Japan, but is almost completely unlicensed – and in many cases unlicensable, as the content is difficult, if not outright impossible to market in the western world.

I learned Japanese to be able to read these books but, for most of the audience, this is neither sensible nor viable. Scanlation of this genre is still driven by love of the genre and desire to share with other fans – this is the motivation of an “ethical” scanlation group.

Let’s take a look at a typical “ethical” scanlation circle as they exist now.

An “ethical” scanlation circle only scans series that are unavailable in their primary language. They strongly encourage their readers (what I refer to as “the audience”) to buy the book (to become “the market”) when it is licensed in that language. They do not charge for their efforts, do not have ads on their website, do not take monetary contributions to their efforts. Ethical scanlators may ask for donations, but are more likely to want resources (bandwidth, seeders, expertise, etc.,) than money. It’s a labor of love. These circles are often composed of people who do buy that original copy or two – and many of their senior members may also purchase the book in the original form to support the creator. Ethical groups pull their versions off the Internet – and ask their fans to stop sharing theirs, should they have them – as soon as news of an official license is announced for a work. And because ethical groups are trying to help, not harm, it’s a high probability that if creators asked them directly to stop scanning their work, they would.

I believe 80% of groups would stop, because as sad as it would make them feel, they really are only trying to help. That would leave 20% who voluntarily enter the real of “criminal” scanlators, in the sense that they know they are going against the creator’s wishes and violating their IP rights, but for whatever reasons, don’t care. Japanese and American manga publishers have just created an alliance to attack this 20% tip of the iceberg. I think this makes sense for them and wish them well at it. It is wholly within their rights and responsibilities to protect their IP. Interestingly, many of the ethical scanlators also dislike the aggregation sites precisely because these sites distribute material they have no right to distribute, i.e., work done by scanlation circles. Ironic as it is.

Despite the ethical scanlators’ best intentions, not all of their audience is as ethical as they are. Not everyone in their audience wishes to support the creators or the publishers. Many plead lack of funds as a sufficient reason to only download scans. Some fans have oddly selective memory and will recall a slight from years ago by a publisher who dropped the ball, and will use that as justification for never buying from that company – even if by doing so they would be supporting a creator whose work they love. For many of the audience scans are their only option, as no companies in their countries have made an attempt to license what they would like to read. For these people, scanlation continues to be fair use of the content.

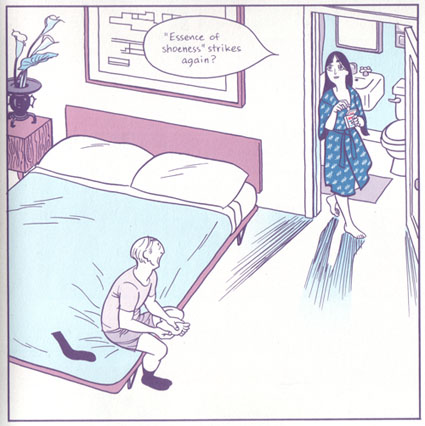

Lastly, there is the issue of translation. One of the pervasive arguments against scanlations is that official translations are better in all ways. Unfortunately, this is very often not the case.

Publishers are bound by contracts, copyright, and requirements from the licensors, creators and market forces. A name may be commonly translated by the fandom in one way only to be altered by the licensor or creator to something that looks/sounds/feels utterly absurd to a western fan. I can remember reading a book in which the main character’s family name was Naitou, but for some reason, the creator wanted it spelled Knight-o…which just looks silly on the face of it. If a character’s name rides the edge of a possible copyright infringement, it must be changed, not because the publisher hates the fans, but because there is no comics publisher around that can afford ongoing lawsuits with major western media companies who guard their copyrights with an absurd, creativity-killing zeal. Publishers are at the mercy of hired translators and editors who they hope are accurate and skilled. And, lastly, publishers are bound by the need to *sell books.* This means that a publisher may make a decision to change something to make the book appeal to more than just the core audience – sometimes at the risk of offending the core audience. Scanlation groups are not bound by any of these issues and are free to translate names in a way that is a common usage among fans, or which makes the most sense.

Scanlation groups often do a tremendous amount of research, to explain puns and literary references, offer historical context, descriptions of military terms, define common honorifics and generally provide the reader with as authentic a reading experience as possible. Publishers, for any number of reasons, will often not do this. In one case I can think of, a licensed series that previously had detailed translation notes has now had them cut back to nearly nothing, so that many of the references simply go undecoded. It might be because of money or time, but many licensed series can’t provide that level of detail. Not every scanlation group does this, of course, nor does every publisher skimp, but I can easily call to mind several series in which the scanlation groups did a better job than the legit publisher and several groups who work is professional quality (in some cases because professionals work with them.)

And, finally, there is the issue of out-of-print material. I will admit that, up until a few years ago, I was providing a scanlation group with material from a magazine that is long out of print, never had collected volumes and was in danger of disappearing, forgotten. I have stopped, because of my shifting feelings about scanlations, but I do not regret having done what I did.

Some of the American comics scan sites distribute back issues – the infamous HTML Comics touted that as their raison d’etre. The owner of this site, which has now been shut down by the FBI, insisted that the companies left him alone because he only made old material available. It’s true that a die-hard fan can find any number of avenues to find and purchase Thor #142, but for a casual reader, it makes no sense to attend a show or hunt online for a single volume that you simply want to read once. That’s why libraries exist in the real world – and there are no pamphlet comics libraries available to the average person in Whatevertown, USA.

The sole problem, really, with scanlations is that they are illegal (and, perhaps, immoral.) The scanlation group is distributing something they do not have the right to distribute. In effect, if they could gain permission from the creator, scans would *still* be a very elegant and simple solution to the problem. Permission is very much the crux of the matter here. Musician David Byrne wrote about a creator’s right to grant permission on his blog, in which he says plainly, “It’s not just illegal because one is supposed to pay for such use and not paying is, well, theft — it’s also illegal because one has to ask permission, and that permission can be turned down.”

So, in the past, the problem was “things I want to read are not available” and the solution was “scanlations.”

Now, what is the current problem? Not scanlations, which are the solution to a previous problem.

I propose that the problem we are really dealing with is this:

1) Readers want what they want to read, in their language, for a reasonable price (or free), in a reasonable time frame, in a format that is not reliant on a single standard, format or hardware.

2) Creators want the right to make decisions about their work, grant access and distribution rights, give *permission* and make a fair wage from their work.

3) Publishers want to be able to sell materials that they have paid to license (or to create) and make enough money in doing so that they can pay their employees, themselves and have money to invest in new properties.

For readers, the problem hasn’t changed all that much. Readers’ expectations have changed, because at this point it seems absolutely absurd that I really can’t just get what I want to read in my language. Regional licensing? Why? Clearly it doesn’t help Czech readers to learn that a Korean version has been licensed, or English readers that France will get a release of a book they’d like to read too. The fact that DVDs are still region encoded when most DVD players are no longer limited by that seems more of a sad memory of some ancient gerrymandering of the planet than anything useful or intelligent. Where is our global economy?

For the creators, the problem hasn’t changed at all. Where once upon a time, the companies took your content, threw you aside, then wrung the content dry, now the fans do it too. Nice way to say “thanks” for all that hard work.

And for the publishers, the problem is seemingly endless and constantly shifting. How to determine what titles are most likely to actually sell, to license work people want, get it to them quickly and with high quality, and for free, then provide a way to sell books as well, without involving a distribution model that relies on some third-party company whose decision-making is schizophrenic at best and seems pretty heavy-handed all the time, or whose hardware requires a proprietary format.

The solution we need must address at least the first two of the above three issues. It’s already clear that publishing is changing, and if the role of publisher disappears into a world in which readers and creators interact directly and meaningfully then I, as a publisher, don’t mind all that much. But, I do think there is a place for publishers in the new solution, even though the concept of “publisher'” will change.

Now, all that has gone before is a discussion of “The Problem,” which was really just the solution to an earlier problem. It’s time to consider the “The Solution” to our new set of problems.

I had this discussion on Twitter and received an enormous amount of excellent feedback. Here are some (not by any means all) of the specs of the new Solution. None of these are my ideas, this is a synopsis of the collective mind.

But, before we move into the specifics, I want to be up front and address the obvious argument against what I am about to lay down – it all seems utterly unreasonable. Of course it is. It’s crazy thinking. Off the rails. This is not a solution that fixes a problem – what we need now is a solution that creates an entirely new vision. I believe that the heart of this new solution is in the core of the old one – the passion and love the fans have for comics and manga. I’ve seen both technology and process shifted by scan groups as a way to better serve their audiences. If we can harness that to begin with, we’ll have a strong start.

The solution needs to be platform- and technology-independent. Not hardware dependent, not company/distributor dependent. Manga Expert Jason Thompson posted recently about how badly the iPad serves manga with schoolmarmish standards of what is “appropriate.” Many articles exist about how Kindle and Nook at this point, are not good for graphic novels. There is more commentary about the increasing difficulty of distribution of printed comics and manga than any one person can really keep up with. We need something better, something that allows creators to make their own decisions about how their work is viewed and readers to make our own decisions about what content we choose to read.

There must be self-regulated community standards so that children can find comics that suit and so can adults, without having to be “protected” from porn by over-zealous hardware gods.

Creators should get payment for every download/view and also reasonable payment for every approved modification, parody or use of their material. For instance, if a creator approves a translation of their comic to Uigur, a small fee (one in proportion to the number of people on the system with that as their primary language) can be paid by a group, so they can then translate that work into their language. The download/view fees will then pay the creator royalties for their content. Comic artists will have control over what happens to their work, and will be paid for the use of it.

“Publishers” will be anyone who is not a creator, but modifies a work by translating, editing, retouching, relettering, etc, for an approved project. This will give passionate fans the ability to share their favorite works in a legitimate manner. Perhaps these “publishers” can get a percentage of the approved projects that are downloaded/viewed. For instance, if that Uigur scan group is composed of 5 people, every time the Uigur translation is read, the translator, editor, proofreader, letterer and retouch person might get a small percentage of the download/view fee. 95% of the fee would get to the creator who approved the work and each of the scanlators might get 1%. Tie scanlation circle ratings to the relative financial success of the work, and the ratings will indicate to a creator not only the skill a circle brings to the problem of translation, but also their marketing strength. Circles will have a direct motivation to make sure the creators make money on their work, or their own ratings will fall.

There needs to be a creator community and a reader community as part of this solution. Every scanlation group has a community and it’s this that keeps the group – and the love – alive. Fan work can/will be encouraged, but also managed. Some creators are already going this route on their own – taking their work online and developing their own methods to monetize it. This solution would provide a home for all creators, worldwide, to do the same, in a way that allows them to focus on their work, not on the technology of distribution.

Reader and system suggestions – and free previews of series that are not in the readers’ normal genres – will help stimulate reading.

And, for those of us who still love the feel, smell and look of books – print on demand capability, with reasonable price points. Like pamphlet comics? As long as the creator gives their approval, each chapter can be printed that way, or as a whole GN volume. The creators will have the opportunity to merchandise directly in the form of whatever products they want – T-shirts, postcards, or limited printed lithographs of a cover piece. It will be up to each creator to decide what they want to do and what form it would take.

Take the passion already put into scanlations, give it the power of community, suggestions and ratings, add the freedom of webcomics, a creator community in multiple languages and above all of this allow *permission* to be granted by the creator and fees to be paid for the use of the content.

I am not smart enough to do this, but I am convinced it can be done. It’s not in a company’s best interest to come up with the solution – companies have to pay bills, they have to protect the IP they have and the status quo of how they work. It’s not in our best interest to let the companies dictate the formats and hardware we use to read our manga.

I challenge all of you out there to create this new solution. And I challenge you to all work on this, not wait for someone else to build it. Scans were developed by fans to solve a problem. Don’t focus on the problem – or why this can’t work – focus on the solution and how it can – then let’s make it happen. Also, let’s lose the fannish binary of either/or. There can be *multiple* streams of distribution in this world. There’s no reason to think that this solution can’t exist parallel to seven other forms of distribution, including magazines and books.

For the creators who want control of our work and readers, who want freedom to enjoy that work in our own way this is an unparalleled opportunity. We can all create a new paradigm that will make readers, creators and publishers equal stakeholders in an industry and in the content we all love.

Erica Friedman is a content creator, a publisher and a reader.

___________

Update: The entire Komikusu roundtable can be read here.