This post is part of a week-long roundtable on xxxHOLic. See Vom Marlowe’s opening salvo here.

I bought the first volume of xxxHOLiC (if you object that that version, mentally fill in the random capitalization convention of your choosing) years ago. I don’t remember how many years ago, but probably in 2004, when it came out. The pages have gotten yellowish and skanky looking, but that doesn’t take long with that newspapery pulp stuff Del Ray uses. It doesn’t matter anyway. The point, if I could manage to shift around to it (ah, there – much more comfortable), is that I read it and I wasn’t moved to buy any more volumes in the series (it’s ongoing, and volume 15 is due out in March). Upon rereading it, and then reading volumes two and three for the first time, I don’t really see the error of my ways.

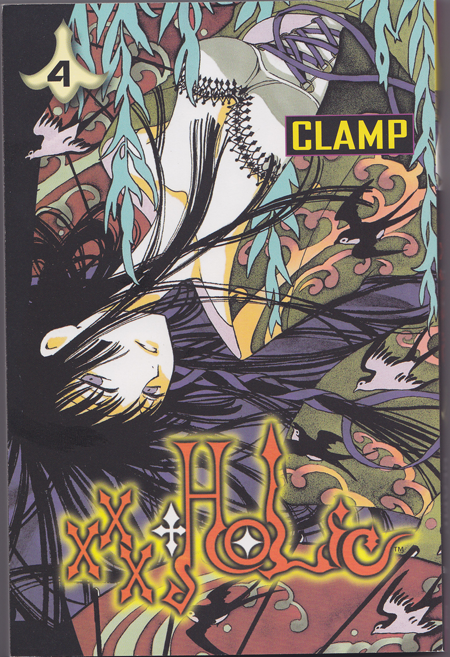

I am a fan of CLAMP, and I don’t dislike xxxHOLiC. Parts of the story amuse and interest me. I loved Cardcaptor Sakura (but not Tsubasa, the sort of second version of it) and Clover and Chobits and Wish. I hated RG Veda and couldn’t really get into Magic Knight Rayearth. I was frustrated by Legal Drug, but I’m not bitter. So, I have some history with CLAMP. I even remember why I got the first issue of xxxHOLiC; I’d seen some of the original color art at an exhibit and, damn, it was amazing. I still think about it occasionally, and my memory is like sieve, but with holes so big it can’t be used as a sieve because everything bigger than a car falls through. So what I’m saying is that aesthetically, this is some fine work.

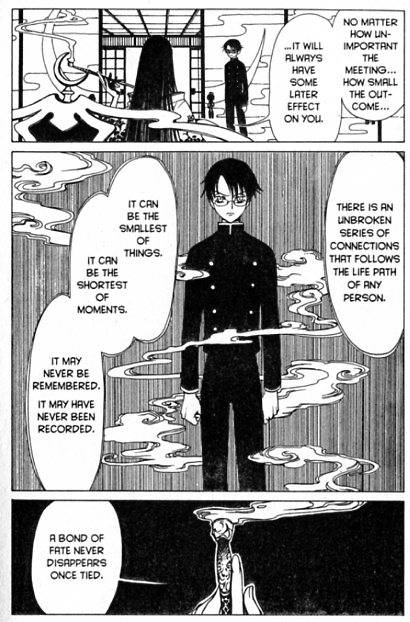

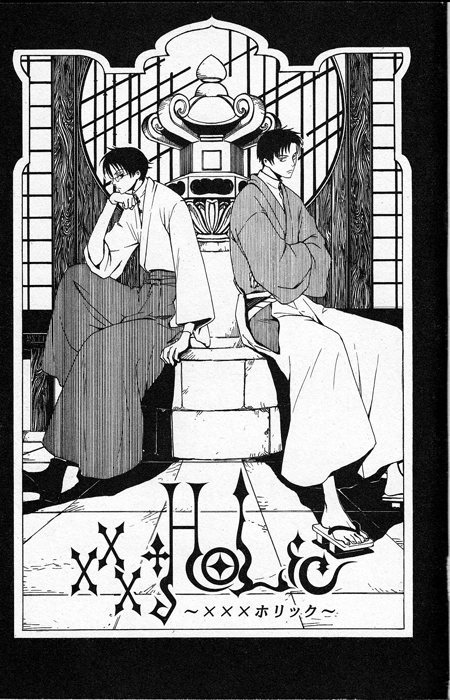

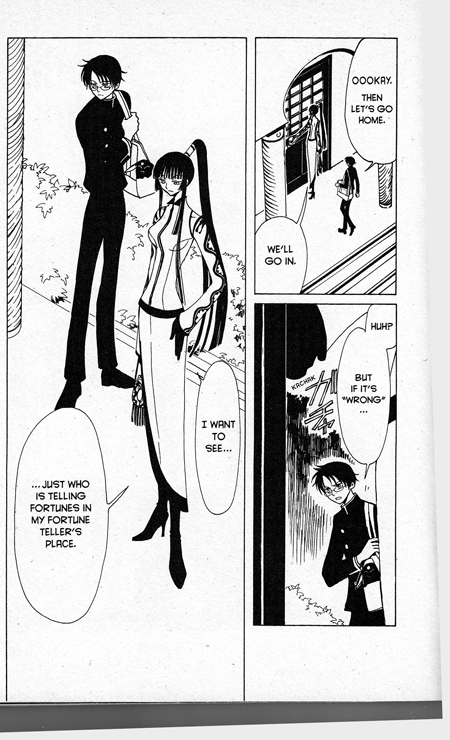

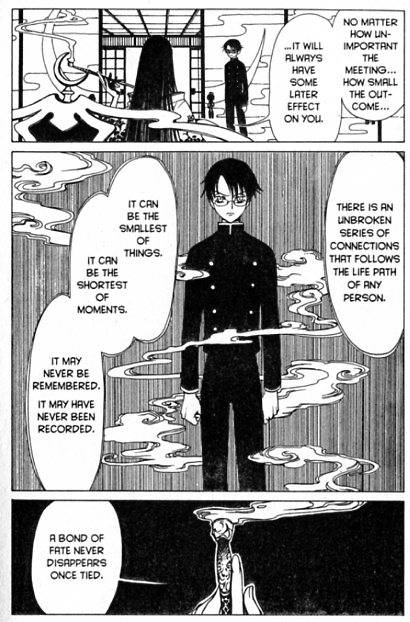

CLAMP is known for that, of course. The design is beautiful, and they also use design to help tell the story, something I, for one, like to see in a comic. For instance, look at this (from volume 1).

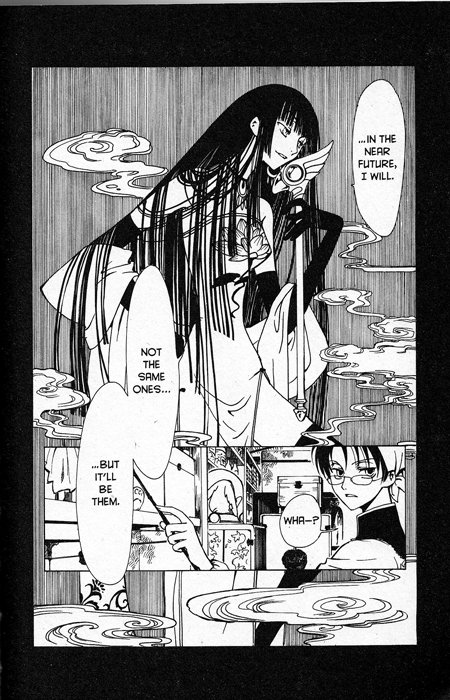

There’s smoke swirling around Yuko – the witch at the center of the series – all the time (well, not literally, but enough to establish the connection). The smoke that drifts up this page is shown on the cover and throughout Yuko’s introductory scene. And it’s echoed here.

This is one of Yuko’s clients. She comes in because she can’t move her little finger. What the hell does that mean? In palmistry, the little finger symbolizes communication, and hands are often used to symbolize divinity in religious iconography. In Buddhism, the Karana mudra (a mudra is a ritual hand gesture), which is made by raising the index and little finger while folding the other fingers down, expels demons and removes obstacles like sickness or negative thoughts. Is that what we’re supposed to be thinking about? Maybe, but damned if I know. It doesn’t seem unreasonable. The woman’s problem is that she’s a compulsive liar, and every time she lies, a beautifully drawn greasy black cloud pours off her. We watch as she tells casual lies everywhere she goes and she starts losing use of other parts of her body – her arm, her neck – and finally her entire body freezes up in front of a big old truck, which ends her sad tale of woe.

I have two major thoughts about this, the first story woven into the series. When I saw the black clouds engulfing this woman, I thought, karma. (Yes, this depiction is also all about the way spirits are depicted in Japanese prints. But I believe it’s fair to think beyond this.) In the west, karma is often understood to be kind of a cosmic vigilant ubercop who will jump out at you if you do something bad and yell “gotcha!” This is a misunderstanding. Let me propose another. I’ve often thought of karma as the maple syrup that accumulates on the outside of the bottle. (Feel free to substitute Kaluah, if you prefer.) You buy a fresh bottle of syrup, and it’s nice and clean and perfect. The first time you use the syrup, a bit of it is likely to drip down the side. Or a lot. Even if you wipe it off, the outside of the bottle remains a bit sticky. The next time you use it, you spill a little more syrup down the side of the bottle. As time passes, maybe some dust or lint gets stuck in there, too, and the layers of spilled syrup build up, and your lovely, pristine bottle of syrup has become a bit of a mess. Or a disgusting thing nobody wants to touch or think about, depending on how sloppy you are and how long you’ve had the syrup. This is how karma works. As you go about the business of living your life, you spill some syrup. It isn’t a punishment or judgment; it just makes things sticky, and you live with it. So it is with the lies this character tells. Nobody affixes a big, red “L” for liar on her chest; nobody even confronts her, even though we see that others realize she’s lying. But the weight of the lies builds and builds until her life is too gummed up to function.

I also thought, wow, that’s kind of extreme, isn’t it? Does she really deserve to get run down by a truck because she tells lies? She isn’t hurting anyone but herself – although there’s a Buddhist argument to be made (while I’m talking about karma) that you can’t really just hurt yourself. Because you are part of the universe, your actions affect the universe. Yadda yadda. Anyway, it seemed surprisingly moralistic, at first glance. But, no; I think it’s just heavy-handed symbolism. The witch keeps saying there’s always a price. What she means is that there are consequences. You don’t get away with anything. You might not understand the harm you’re causing, and the cosmic judge might not jump out and finger you for your transgression (that was a little joke – we were talking about her little finger, so – oh, never mind) – but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a price. You live with the syrup residue, and it leads to the situations it leads to, whether you realize what’s happening or not.

The witch tries to explain this more explicitly in the next scenario of volume 1 – a situation that resonated with me, I must say. This client is a woman who is addicted to the Internet. She neglects her children and her housework in favor of her online connections. But the woman in the story wants to change. Unlike some, she is concerned about being a good wife and mother. She tells Yuko so, but the witch is suspicious and tries to make her understand that, basically, it is what it is. Maybe she really doesn’t want to be a good wife and mother; maybe she really wants to tell her family to sod off so she can spend all her time online. There’s a choice to be made, and pretending that isn’t the case doesn’t change it.

Volume 2 is different in structure, concentrating on the main characters instead of the little vignettes about the clients. This isn’t ideal, in my opinion. Because I’d sort of thought I didn’t especially like the main characters, in volume 1, but I kept getting distracted. Taking away the distractions (except for a brief appearance by four characters from Tsubasa, which was supposed to be delightful but just made me feel a little hunted) made this clear to me. (They also stop by Legal Drug, which caused me to stop and say, “Hey! They stopped at Legal Drug!” But that was a very fleeting pleasure, really.) This volume sets up the romance or whatever between Watanuki (the kind of annoying kid who is mystically drawn to Yuko’s place who I didn’t mention in my ramblings about the first volume because I really didn’t give a damn about him as a character) and the maddeningly over-cute Himawari (a girl with big, aggressive curls and, apparently, a secret – dum dum dum!!!!). (Wikipedia will tell you what the secret is, if you care. Kind of lame, I thought. Whatever you’re thinking it is, that’s probably better.)

Yuko tries to make the really maddeningly stupidly jealous and competitive Watanuki understand that he needs his schoolmate, Whatshisname, to get rid of the spirits that chase Watanuki around. Watanuki’s problem with the spirits is what led him to the witch’s house anyway, and it’s a big deal, not a minor problem like continually forgetting to pay the mortgage on time or something. So I kept thinking that Watanuki would grasp at any solution, no matter how immature he is, but apparently not. CLAMP did warn me that “This isn’t the kind of story where understanding makes you smart, or not understanding makes you dumb.” Anyway, Yuko saves the day (for the reader) by arranging for these four characters – her, Watanuki, the annoying cute girl, and the strong, silent, tall, and handsome guy Watanuki is jealous of – to get together and tell ghost stories. I liked the ghost stories. Japanese ghost stories tend to be understated and quietly creepy in a way that appeals to me.

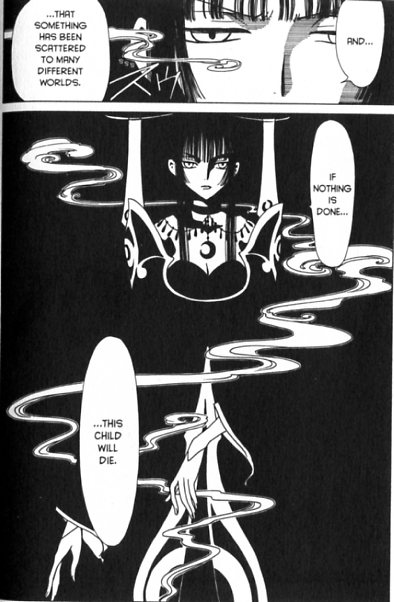

That smoke is still there, by the way. I’ll stop pointing it out, but I do like it. Check out this page – just beautiful.

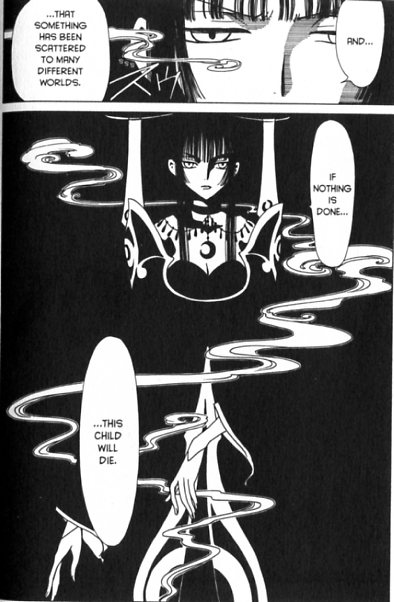

Right, then. On to volume 3. We get a couple of adventures in this book, one with Watanuki and that guy whose name I can’t remember, and one with a client, of sorts. In the first story, Yuko sends the boys into a school where the students have stirred up spiritual nastiness by playing a game that’s the Japanese equivalent of the Ouija board. Things get dire, but then a huge snake spirit comes along and eats the Ouija-based miasma. Yuko explains that the snake showed up to clean up something that had gotten out of balance in its area, and that none of the spirits are good or evil, even though they were trying to kill our protagonists; good and evil are just concepts assigned by people. Very Buddhist, that. I’m all for it, but I felt like the following story, about a monkey’s paw, spirals a bit out of control itself (but the snake spirit is nowhere to be seen).

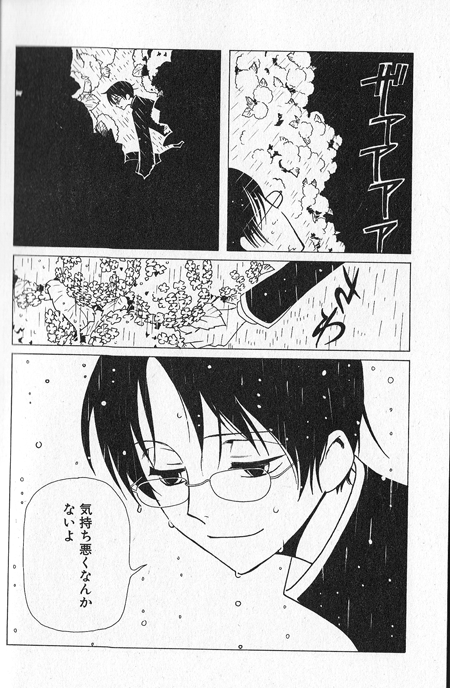

In the monkey’s paw story, a blithe young woman is drawn to the witch’s house (by fate, or, more accurately, karma, I think) and asks for a sealed cylinder. Yuko gives it to her on the condition that she Never Open It. Yeah, right. Well, something happens, the cylinder opens, and there it is. Everyone knows a monkey’s paw is bad news, but this woman (I don’t think we find out her name, and I’m running out of steam with these books, so I’m disinclined to go back and check) explains that she’s extremely lucky and always gets what she wants, so she isn’t worried about wishing on the nasty-looking thing. Her first wish is for rain, just to prove it works. There is a sudden downpour, and the next day we find out the consequence – all the water is gone from the school pool! Gasp! Now, I don’t want to go out of my way to be snarky about CLAMP, but this is lame with an almost unbearable lameness. Next, the woman wishes for an antique mirror she’d been trying to talk some shop-owner into selling to her. Poof! The Yata no Kagami, coming up! (I think that’s a Naruto reference. This whole crossover thing is not lighting my fire.) This is a sacred object that represents wisdom and/or honesty. That’s a bit ham-fisted too, but OK. I can live with it, especially after the pool fiasco. Next, the woman wishes for a topic for her upcoming seminar, and she gets a brilliant lesson plan. Now, the way this works, in case you haven’t read a monkey’s paw story, is that a finger breaks after each wish. Five fingers, five wishes. So after this seminar success, she has two wishes left and is really feeling on top of the world. But then she’s late for an important class and thinks, wow, if only there were a HORRIBLE ACCIDENT! Then I could show everyone the police report and I wouldn’t get in trouble! You’re ready for it, right? Yep, the man next to her falls onto the track and is killed by a train. Oh, dear! Maybe this repulsive dead animal part is bad news! A random stranger dies, and then our heroine gets in trouble because the monkey paw actually stole her brilliant lesson plan from somebody else, and she’s been caught. Now she worries she’ll be blamed for the death of the stranger, too, since he was standing next to her. Finally concerned, she unfurls her fifth wish – for the monkey’s paw to make this right. So it strangles her. Move along – nothing to see here.

Well, I thought about this tale a lot more than I should have. I was immensely cheered when the monkey’s paw first made its appearance. I mean, a monkey’s paw! That was going to have to be fun, wasn’t it? But I think CLAMP lost control of the metaphor. Good and evil are relative concepts, we must expect consequences for our actions, and so on. But when the happy-go-ultimately-not-so-lucky lady’s saga is over, Yuko says, “She thought that the disaster that is brought on by breaking a promise would never come down on her head.” That sounds more “gotcha” than I’m comfortable with.

Now, there is a delightful little story at the end of volume 3 that succeeds on all levels. It is my favorite thing in xxxHOLiC, charming in the way I wish the rest of the series were. Watanuki runs across an udon stand run by a fox spirit. (It’s a sweet little joke, as fox spirits are said to like the fried tofu in kitsune udon.) The idea is cute, the foxes are cute, the whole thing is cute. The young fox of the house is drawn to the feathered end of a broken arrow in Watanuki’s bag, and all the foxes are pleased when Watanuki gives it to the kit. If anyone knows what the arrow symbolism is, I’d love to know.

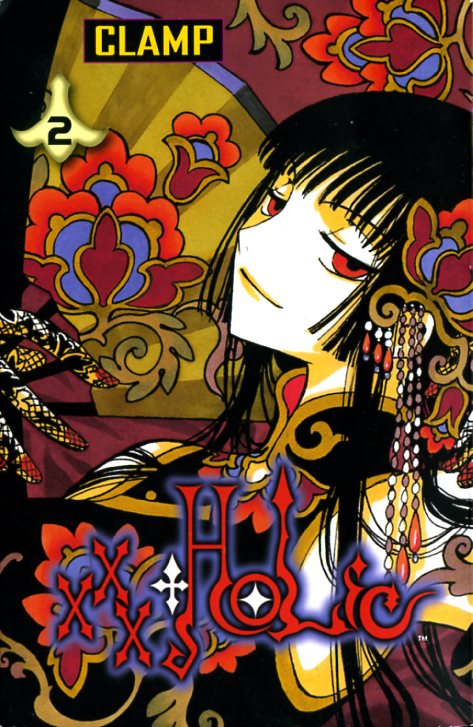

So, I’ve pushed past volume one and through two and three. Am I going to finish the series now, as I am prone to do? No. It’s OK; enjoyable, even, but nothing moves me to read any more of it. This is interesting (to me) because I did read the entire Pet Shop of Horrors series (by Matsuri Akino), which was released starting in June 2003 in the United States and 1996 in Japan. (xxxHOLiC was released starting in 2004 in the United States and 2003 in Japan.) It’s hard not to compare them, although that comparison might actually be fairly random. xxxHOLiC stars a beautiful, playful, flirty, and mysterious figure whose occult significance is obvious but never quite explained and who likes to lounge about wearing sexy Chinese clothes. (Sometimes, anyway. That thing on the cover of volume 2 certainly looks cheongsam-like.) Clients come to her store (albeit not of their free will) to get a wish granted, often much to the wisher’s detriment. Pet Shop of Horrors stars a beautiful, playful, flirty, and mysterious figure whose occult significance is obvious but never quite explained and who also likes to lounge about wearing sexy Chinese clothes. Clients come to his store to buy exotic pets that will, more or less, grant the owner’s wish, often much to the wisher’s detriment. (There are contracts, and the clients break them; that seems very much like the monkey’s paw thing, for instance.) This sexy witch-like figure is a man, but that isn’t a major deviation, believe me. Yuko drinks and flirts and partially falls out of her various improbable outfits, while Count D eats cake and flirts and never seems in danger of falling out of his various improbably outfits, but they do make you wonder. xxxHOLiC wins by a mile in the categories of art and design (and color – I seldom wish with all my heart that an entire manga could be done in color, but I do with this one), but Pet Shop of Horrors wins for storytelling. So sayeth Kinukitty, anyway.

Oh, and one last thought. Perhaps you were wondering how the hell you’re supposed to pronounce “xxxHOLiC.” I found it somewhat vexing, actually. When I thought about it. So, twice. Anyway, Wikipedia comes to the rescue again, explaining that it’s just “holic.” The Xs aren’t letters but multiplication symbols, standing in for crosses, which indicate relationships or crossovers in Japan. The “holic” part seems to be standard usage. As for the weird capitalization, I don’t know. Let’s just ignore it.

_____________

Update by Noah: You can read all posts in the xxxholic roundtable here.